Journal of Management

http://jom.sagepub.com/

Do ''high commitment'' human resource practices affect employee commitment? : A crosslevel analysis using hierarchical linear modeling

Ellen M. Whitener Journal of

Management 2001 27: 515 DOI:

10.1177/014920630102700502

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://jom.sagepub.com/content/27/5/515

Published by:

®SAGE

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

SMA

SOUTHERN MANAGEMENT

Southern Management Association

Additional services and information for Journal of Management can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://jom.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://jom.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://jom.sagepub.com/content/27/5/515.refs.html

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

Pergamon

JOURNAL OF

Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

MANAGEMENT

Do “high commitment” human resource practices affect

employee commitment? A cross-level

analysis using hierarchical linear modeling

Ellen M. Whitener*

Department of Management, McIntire School of Commerce, University of Virginia, Charlottesville,

VA 22903, USA

Received 20 September 1999; received in revised form 7 September 2000; accepted 27 November 2000

Abstract

Relying on a cross-level paradigm and on social exchange theory (i.e., perceived organizational

support) I explore the relationships among human resource practices, trust-in-management, and

organizational commitment. Individual-level analyses from a sample of 1689 employees from 180

credit unions indicate that trust-in-management partially mediates the relationship between perceived

organizational support and organizational commitment. Cross-level analyses using hierarchical linear

modeling indicate that human resource practices affect the relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational commitment or trust-in-management. © 2001 Elsevier Science Inc.

All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

In a survey of over 7500 U.S. workers, Watson Wyatt International found that companies with

highly committed employees experienced greater 3-year total returns to shareholders (112%) than

companies with low employee commitment (76%; Watson Wyatt, 1999). They also found that human

resource practices and trust in management had the strongest impact on building commitment.

As Watson Wyatt’s survey implies, human resource practices and trust may provide two avenues

that corporate executives can use to increase the commitment of their workforce.

* Tel.: +1-434-924-7091; fax: +1-434-924-7074. E-mail

address: emw8r@virginia.edu (E.M. Whitener).

0149-2063/01/$ - see front matter © 2001 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. PII:

S 0 1 4 9 -2 0 6 3 (01)00106-4

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

516

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

Academic research conducted at the organizational level suggests that human resource

practices affect organizational outcomes by shaping employee behaviors and attitudes

(Arthur, 1994; Huselid, 1995; Wood & de Menezes, 1998). More specifically, systems of

“high commitment” human resource practices increase organizational effectiveness by

creating conditions where employees become highly involved in the organization and work

hard to accomplish the organization’s goals (Arthur, 1994; Wood & de Menezes, 1998)—in

other words, by increasing their employees’ commitment to the organization. However,

ironically, these studies have provided estimates of the strength of the relationship between

high commitment human resource practices and measures of organizational effectiveness

without investigating the relationship between human resource practices and employee

commitment.

Similarly, researchers have not systematically developed or tested theories linking trust

and commitment; however, incidental to tests of other variables or theories, they have found

significant correlations between commitment and employees’ trust in a specific individual

(e.g., their supervisor or leader) (Folger & Konovsky, 1989; Pillai, Schriesheim & Williams,

1999; Podsakoff, MacKenzie & Bommer, 1996) or generalized trust-in-management (e.g.,

Gopinath & Becker, 2000; Kim & Mauborgne, 1993; Pearce, 1993). These estimates suggest

that further study of the nature of the relationship between trust and commitment would be

fruitful, especially if theory-based.

The motivational processes of social exchange theory and the norm of reciprocity (e.g.,

Blau, 1964; Homans, 1961) may explain the relationships among human resource practices,

trust-in-management and employee commitment (Eisenberger, Fasolo & Davis–LaMastro,

1990; Settoon, Bennett & Liden, 1996; Wayne, Shore & Liden, 1997). A well-established

stream of research rooted in social exchange theory has shown that employees’ commitment

to the organization derives from their perceptions of the employers’ commitment to and

support of them (Eisenberger et al., 1990; Hutchison & Garstka, 1996; Settoon et al., 1996,

Shore & Tetrick, 1991; Shore & Wayne, 1993; Wayne et al., 1997). The research suggests

that employees interpret organizational actions such as human resource practices (Settoon et

al., 1996; Wayne et al., 1997) and the trustworthiness of management (Eisenberger et al.,

1990; Settoon et al., 1996) as indicative of the personified organization’s commitment to

them. They reciprocate their perceptions accordingly in their own commitment to the

organization. Only a few studies have explored the role of human resource practices in this

model (e.g., Allen, 1992; Guzzo, Noonan, & Elron, 1994; Miceli & Mulvey, 2000; Wayne

et al., 1997) and none has explored the role of trust.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationships among human resource

practices, trust-in-management, perceptions of organizational support, and organizational

commitment. I rely on a “meso” paradigm recognizing that these variables exist at different

levels of analysis (organizational and individual) but nonetheless interact and affect each

other (House, Rousseau & Thomas–Hunt, 1995; Rousseau, 1985). I use a social exchange

lens relying specifically on the role of perceptions of organizational support to explore the

processes that link these factors. I test the relationships with data from a sample of over 1600

employees from 180 credit unions. I explore individual-level hypotheses using hierarchical

linear regression and cross-level hypotheses using hierarchical linear modeling.

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

517

2. High commitment human resource practices

Human resource practices can be classified as “control” or “commitment” practices

(Arthur, 1994; Walton, 1985; Wood & de Menezes, 1998). Control approaches aim to

increase efficiency and reduce direct labor costs and rely on strict work rules and procedures

and base rewards on outputs (Arthur, 1994). Rules, sanctions, rewards, and monitoring

regulate employee behavior (Wood & de Menezes, 1998). In contrast, commitment approaches aim to increase effectiveness and productivity and rely on conditions that encourage

employees to identify with the goals of the organization and work hard to accomplish those

goals (Arthur, 1994; Wood & de Menezes, 1998).

The practices that represent a high commitment strategy include sets of organization-wide

human resource policies and procedures that affect employee commitment and motivation.

They include selective staffing, developmental appraisal, competitive and equitable compensation, and comprehensive training and development activities (Ichniowski, Shaw &

Prennushi, 1997; MacDuffie, 1995; Snell & Dean, 1992; Youndt, Snell, Dean & Lepak,

1996).

A review by Delery (1998) shows that early studies of human resource practices attempted

to find the universally best conduct of each independent practice. However, recently results

have also shown that high commitment practices can work well synergistically, reflective of

a general commitment strategy. Across a variety of industries (e.g., automotive assembly

plants, steel companies and minimills, not-for profit organizations), organizations with high

commitment systems experience greater productivity, financial performance, and effectiveness than organizations with low commitment or control systems (e.g., Arthur, 1994;

Delaney & Huselid, 1996; Huselid, 1995; Ichniowski et al. 1997; MacDuffie, 1995; Wood

& de Menezes, 1998; Youndt et al., 1996). The organizational context (e.g., fit) and goals

(e.g., outcomes) may impact whether particular human resource practices have synergistic or

independent effects on firm outcomes (Delery, 1998).

3. Social Exchange Theory

Social exchange theory (Blau, 1964; Homans, 1961) originally explained the motivation

behind the attitudes and behaviors exchanged between individuals. Eisenberger, Huntington,

Hutchison, and Sowa (1986) expanded this work by proposing and establishing that the

theory of social exchange and the norm of reciprocity also explain aspects of the relationship

between the organization and its employees. They noted that employees form general

perceptions about the intentions and attitudes of the organization toward them from the

policies and procedures enacted by individuals and agents of the organization, attributing

human-like attributes to their employer on the basis of the treatment they receive (Levinson,

1965). In this way, employees see themselves as having a relationship with their employer

that is parallel to the relationships individuals build with each other.

Recognizing this tendency to personify the organization, they applied social exchange

theory to the relationship between the personified organization and its employees. In

particular, they predicted that “. . . positive, beneficial actions directed at employees by the

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

518

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

organization and/or its representatives contribute to the establishment of high-quality exchange relationships. . . that create obligations for employees to reciprocate in positive,

beneficial ways” (Settoon et al., 1996, p. 219).

3.1. Perceived organizational support, trust, and commitment

Eisenberger et al. (1986) developed the construct, perceived organizational support, to

reflect employees’ beliefs about the organization’s support, commitment, and care for them.

They proposed that perceived organizational support would be significantly related to a

variety of employee attitudes and behaviors including organizational commitment and trust

(Eisenberger et al., 1990).

Organizational commitment refers to identification with organizational goals, willingness

to exert effort on behalf of the organization, and interest in remaining with the organization

(Mowday, Steers & Porter, 1979). Employees’ commitment to the organization would be

significantly related to their perceptions of the employer’s commitment to them (perceived

organizational support) as they reciprocate their perceptions of the organization’s actions in

their own attitudes and behavior (Shore & Tetrick, 1991). Perceived organizational support

has a high and significant correlation (0.38–0.71) with organizational commitment; yet,

construct validity studies have verified that they are distinct though closely linked variables

(Shore & Tetrick, 1991). In this study, I expect to replicate these results:

Hypothesis 1: Employees’ perceptions of organizational support will be positively and

significantly correlated with their commitment to the organization.

Trust is a complex phenomenon that has long eluded precise definition because it

encompasses many facets and levels that need to be carefully specified (Rousseau, Sitkin,

Burt & Camerer, 1998; Whitener, 1997). Rousseau et al. (1998) recognized these difficulties

noting that trust can be different depending on the focal object and level (such as interorganizational vs. interpersonal trust). However, they asserted that the primary components of

trust—risk, uncertainty, and interdependence—remain constant across contexts. Relying on

these elements, Rousseau et al. defined trust as a “psychological state comprising the

intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or

behavior of another” (Rousseau et al., 1998, p. 395). This definition suggests that employees’

trust in management reflects employee faith in corporate goal attainment and organizational

leaders, and to the belief that ultimately, organizational action will prove beneficial for

employees (Kim & Mauborgne, 1993).

Like perceived organizational support, trust develops through a social exchange process

in which employees interpret the actions of management and reciprocate in kind. “. . . The

gradual expansion of the exchange permits the partners to prove their trustworthiness to each

other. Processes of social exchange, consequently, generate trust” (Blau, 1964, p. 315).

According to Eisenberger et al. (1986), perceived organizational support embodies the social

exchange process, reflecting employees’ interpretations and perceptions of the organization’s

actions. Trust in management, who tends to be the primary purveyor of the personified

organization’s actions, is a likely response to their perceptions. On this basis, I predict a

significant relationship between perceived organizational support and trust such that:

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

519

Hypothesis 2: Employees’ perceptions of organizational support will be positively and

significantly correlated with their trust in management.

Similarly, researchers (e.g., Gopinath & Becker, 2000; Kim & Mauborgne, 1993; Pearce,

1993) have estimated the strength of the relationship between organizational commitment

and employees’ trust in management. They have found significant correlations ranging from

0.42 to 0.61. I expect to replicate these past results such that:

Hypothesis 3: Employees’ commitment to the organization will be positively and

significantly correlated with their trust in management.

Hypotheses 1 through 3 suggest that trust, perceived organizational support, and commitment are inter-related. Indeed, Eisenberger et al. recognized links among perceived organizational support, trust and commitment when they noted “perceived organizational support

would also enhance calculative involvement [an aspect of commitment] by creating trust that

the organization will take care to fulfill its exchange obligations. . . ” (Eisenberger et al.,

1990, p. 52). Although they did not elaborate, they seem to be suggesting that trust in

management mediates the relationship between employees’ perceptions of the organization’s

support and commitment and their own commitment response.

Several studies looking at other kinds of perceptions (e.g., procedural fairness or individuals’ support) have generated results consistent with this notion. Individuals’ trust builds as

a response to their perceptions of the actions of another and leads to an increase in their

commitment to that actor (Folger & Konovsky, 1989; Gopinath & Becker, 2000; Pillai et al.,

1999; Podsakoff et al., 1996). These results suggest a perfectly mediated relationship in

which perceptions are associated with commitment only indirectly through trust; however, in

this context, the relationship between perceived organizational support and commitment is

likely to include a direct link as well. Because the correlations between perceived organizational support and commitment found in previous research (0.38–0.71) are so similar to

the correlations between trust and commitment (0.42–0.61), the relationship between perceived organizational support and trust would have to be perfect (1.0) for trust to perfectly

mediate the relationship between perceived organizational support and commitment. These

previous results suggest a partially mediated model instead such that:

Hypothesis 4: Employees’ perceptions of organizational support will be related to

employee commitment directly as well as indirectly through their trust in management.

3.2. Human resource practices, perceived organizational support, trust-in-management, and

commitment

Ostroff and Bowen (2000) relied on social exchange and the norm of reciprocity in

developing hypotheses about the relationships among human resource practices, attitudes,

and performance. They proposed that human resource practices shape work force attitudes by

molding employees’ perceptions of what the organization is like and influencing their

expectations of the nature and depth of their relationship with the organization. Employee

attitudes and behaviors (including performance) reflect their perceptions and expectations,

reciprocating the treatment they receive from the organization. In their multilevel model

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

520

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

linking human resource practices and employee reactions, they depicted relationships suggesting that human resource practices are significantly associated with employee perceptions

and employee attitudes.

In the only study testing these relationships that explicitly recognizes the cross-level

nature of the research questions, Tsui and her colleagues (Tsui, Pearce, Porter & Tripoli,

1997) found that employee attitudes (specifically employee commitment) were associated

with the interaction of human resource practices and perceptions. They analyzed data from a

sample of 10 organizations and over 900 employees in 85 jobs. They conducted their

analyses at the individual-level but controlled for job-level differences in organizational

support. They found that employee commitment is associated with the interaction of human

resource practices (e.g., performance appraisal and rewards) and support.

These results are consistent with research on perceived organizational support. Several

studies have indicated that perceived organizational support interacts with organizational

actions (including human resource practices) in affecting employee commitment (Allen,

1992; Guzzo et al., 1994; Miceli & Mulvey, 2000; Wayne et al., 1997). Therefore, rather

than just looking at direct relationships, I investigate the impact of the interaction of human

resource practices and perceptions on employee attitudes in the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5: Human resource practices will moderate the relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational commitment such that the relationship

will be stronger under commitment human resource practices than control human

resource practices.

Hypothesis 6: Human resource practices will moderate the relationship between perceived organizational support and trust-in-management such that the relationship will

be stronger under commitment human resource practices than control human resource

practices.

These hypotheses are consistent with the general notion that human resource practices

interact with perceptions of organizational support to affect employee commitment. However, some human resource practices are more likely than others to have significant relationships (Delery, 1998). Huselid (1995) suggested that human resource practices group into

two categories—those practices that improve employee skills and those that enhance employee motivation. In a study of over 900 organizations in the United States, he validated

these two categories and their effects. He found that skill-enhancing human resource

activities included selection and training activities and were associated with turnover and

financial performance and that motivation-enhancing activities included performance appraisal and compensation activities and were associated with measures of productivity.

Because they can provide direct and substantial harm or benefit to employees (Mayer &

Davis, 1999), motivation-oriented human resource activities are more likely to be associated

with perceived organizational support and commitment than skill-oriented activities. Indeed,

selection and training activities may not even be very salient to employees. Although job

candidates pay close attention to selection procedures, current employees are more likely to

be focused on the job itself. Similarly training activities are infrequent occurrences. Even at

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

521

the “100 best companies to work for” employees spend only 2% of their work-year (an

average of 47 hr a year) in training (Levering & Moskowitz, 2000).

In contrast, performance appraisal and compensation processes have regular and

powerful effects on employees. Poorly designed or conducted appraisal systems can fail to

accurately evaluate the quality or quantity of performance. Compensation systems,

especially those linked to performance assessments, can miss providing salient rewards to

the right people in a timely fashion. These flaws have the potential to under-reward

deserving individuals and over-reward undeserving individuals. Aware of their vulnerability

to the vagaries of badly designed appraisal and reward systems, employees are likely to

perceive well-designed, developmental performance appraisals and internally equitable and

externally competitive compensation systems (Snell & Dean, 1992) as indicative of the

organization’s support and commitment to them. As discussed above, employees would

reciprocate their perceptions of the organization’s support and commitment conveyed by

appraisal and compensation practices with their own commitment to the organization.

In the same way, employees are likely to reciprocate their perceptions of support conveyed

by appraisal and compensation activities in their trust in management. Whitener (1997) also

relied on social exchange theory to predict that trust-in-management is associated with

human resource practices through their effects on employees’ perceptions of support. In a

longitudinal, quasi-experimental study conducted at the individual level, Mayer and Davis

(1999) found that the implementation of a “more acceptable” performance appraisal system

increased employees’ trust in management. They also found that employees’ perceptions of

management’s ability, benevolence, and integrity mediated the relationship between their

perceptions of the performance appraisal system and trust-in-management. Mayer and Davis’

purpose was to test somewhat different constructs and relationships; yet, their results reflect

the same pattern suggested by social exchange: human resource activities are associated with

employee attitudes through their perceptions.

Hypothesis 7: The patterns of relationships among human resource practices, perceived

organizational support, trust-in-management, and organizational commitment will be

stronger for performance appraisal and compensation human resource practices than for

selection and training.

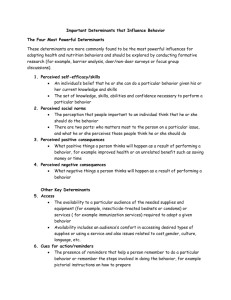

4. Summary

Taken together, these hypotheses imply a framework (depicted in Fig. 1) in which trustin-management mediates the relationship between perceptions of organizational support and

employee commitment and human resource practices moderate the relationships between

perceptions of organizational support and both trust and commitment. As described below,

the individual-level relationships in the framework are tested using hierarchical multiple

regression and the cross-level relationships are tested using hierarchical linear modeling.

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

522

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

Fig. 1. Cross-level framework depicting hypotheses linking human resource practices, perceived organizational

support, trust-in-management, and employee commitment.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Sample and procedures

I worked with research associates from credit union associations to identify and contact

the sample. We drew the sample from the population of credit unions in the United States.

In 1996, the year this study was conducted, there were approximately 12,000 credit unions

in the U.S. Most of them (75%) were small, with assets of less than $25 million and fewer

than 10 employees. One percentage was large, with assets of more than $500 million and an

average of 350 employees.

The research associates generated a stratified random sample of 500 credit unions from

their database of credit unions. We excluded the small credit unions, those with assets below

$25 million, because they have too few employees. We were concerned that it would be

difficult to preserve their confidentiality and that they would not have a formal human

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

523

resource function. We slightly oversampled large credit unions, with assets over $1 billion,

because there are so few.

We mailed letters describing the study and requesting participation to the CEO of each

credit union. We also included the human resource and employee surveys. We instructed the

CEO to ask the senior human resource officer to complete the human resource practices

questionnaire and to organize the distribution, collection, and return of employee surveys in

a way to preserve the anonymity of participants. We included identification information on

the human resource survey; however, the employee survey included no identifying

information. In addition, the employee survey was contained in a booklet with an opaque

cover sheet on the front and back. Employees stapled their survey closed inside the cover

sheet so that their responses were completely hidden. The human resource contact returned

all surveys unopened to the research team. The research team was instructed to identify any

surveys that had been opened and restapled. None appeared to have been tampered with.

Of the 500 credit unions contacted, 185 returned all or part of the survey for a response

rate of 37%. Respondents varied by asset size ($27 million to $8,700 million with a mean of

$326 million), number of members (2000 to 2,000,000 with a mean of 65,912), and number

of full time equivalent employees (12 to 3035 with a mean of 133). A comparison of

respondents to nonrespondents by the credit union research affiliate provided no evidence of

response bias.

The human resource practices survey asked human resource managers to describe their

credit union’s staffing, training, compensation, and performance appraisal practices. Of the

185 organizations, 182 provided complete data on their human resource practices.

The employee survey assessed employees’ commitment to the organization, perceptions

of organizational support, and trust-in-management. Human resource managers were asked

to pick 10 employees to complete the surveys and most indeed returned 10. The number of

employees responding from each credit union averaged a mean of 9.37 and mode and median

of 10 employees per credit union. One credit union only returned one employee survey;

another made copies and returned 18. The remaining credit unions provided at least 5 and no

more than 10 employee usable responses. The two outliers were removed from the database,

yielding a total sample of 180 credit unions and 1689 employees.

The average employee respondent was 36 years old and had worked for 6.7 years at his

or her credit union. Most were full time (92.5%) and female (83%). Three percentage held

executive positions, 25% held management or supervisory positions, 43% held professional

staff positions and did not supervise subordinates, and 29% were administrative assistants or

tellers.

5.2. Measures

5.2.1. Human resource practices

The human resource practices survey contained scales developed by Snell and Dean

(1992) to measure high commitment human resource practices: selective staffing measures

the extensiveness of the firm’s selection process; comprehensive training measures the

extensiveness of the firm’s training and development process; developmental appraisal

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

524

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

measures whether performance appraisal is used for developing employees; externally

equitable reward systems measured the extent to which the organization’s pay levels were

competitive with similar organizations; and internally equitable reward systems measured the

extent to which the organization’s pay structure was equitably construed. Scales ranged from

1 to 5 but the anchors varied depending on the question. For example, the response for the

staffing item, “How extensive is the employee selection process for a job?” ranged from “not

extensive (1) to ”very extensive (5). The response for the comprehensive training item, “How

much priority is placed on training employees?” ranged from “very little” (1) to “a great

deal” (5).

Snell and Dean (1992) provided little evidence of the construct validity of their measures,

conducting only an exploratory factor analysis, so I replicated their procedure and took

several additional steps to explore their psychometric properties (Hinkin, 1995; 1998). First,

an exploratory factor analysis (principle components and varimax rotation) yielded five

factors consistent with those proposed by Snell and Dean. A confirmatory factor analysis,

however, did not fit the factors well yielding a x2 of 1276.78 (df. = 395), with NFI = 0.60

and CFI = 0.68. To explore whether greater parsimony would increase the fit, I evaluated the

top four items for each scale using confirmatory factor analysis. The five factor model

(developmental appraisal, selective staffing, comprehensive training, internally equitable

rewards, and externally competitive rewards) fit the data significantly better yielding a x2 of

393.72 (df. = 160), with NFI = 0.79 and CFI = 0.86. In addition, this five-factor model fit

the data better than a one factor model representing the whole system of high commitment

human resource practices (j(2 = 1006.60, df. = 170, NFI = 0.46 and CFI = 0.50). On this

basis the four-item scales were retained to measure human resource practices. Coefficient

alpha for these scales fell within acceptable levels ranging from 0.70 (staffing) to 0.86

(training).

5.2.2. Employee attitudes

Well-established scales were used for each attitude. Perceived organizational support was

measured with Eisenberger’s scale (Eisenberger et al, 1986). The positively worded items

from the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (Mowday et al, 1979) measured organizational commitment. Their items reflect the extent to which the employee is willing to put

in a great deal of effort beyond that normally expected and the extent to which the employee

“talks up” the organization as a great place to work. Robinson and Rousseau (1994)

developed a scale to measure employees’ trust in their employer. Items include “I am not sure

I fully trust my employer (R)” and “In general, I believe my employer’s motives and

intentions are good.”

These items were also subjected to an exploratory factor analysis yielding three scales.

Scales comprised of the top four items were evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis.

The results indicated that a three-factor model (j(2 = 521.72, df. = 51, NFI = 0.97 and CFI =

0.97) fit the data better than a one-factor model (j(2 = 3741.47, df. = 54, NFI = 0.80 and CFI

= 0.80). Coefficient alpha for each scale fell in acceptable and usual ranges from 0.85 (trustin-management) to 0.90 (employee commitment).

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

525

5.3. Data analysis

5.3.1. Individual-level analyses

As indicated above, I analyzed the individual-level data using multiple regression. With

Hypothesis 4, which predicts that trust-in-management mediates the relationship between

perceived organizational support and commitment, I used hierarchical multiple regression to

assess the three conditions to demonstrate mediation: (1) a significant relationship between

the mediator and the dependent variable, (2) a significant relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable, and (3) the relationship between the independent

variable and the dependent variable decreasing or becoming nonsignificant when the mediator is added to the step (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

5.3.2. Cross-level analyses

As indicated above, hierarchical linear modeling allows for the iterative investigation of

multiple levels of relationships with individual-level dependent variables (Hofmann, 1997;

Hoffman, Griffin & Gavin, 2000). A “level 1” analysis estimates parameters describing the

relationship(s) between independent and dependent variables within each group, that is, at

the individual level. The parameters depicting the relationships (the intercept and slope

estimates) become the dependent variables for the “level 2” analysis that assesses the role of

the higher order (e.g., group or organizational) variables. Significant coefficients on predictors of the intercepts and slopes provide evidence of the cross-level relationships.

Several conditions must be established before testing specific hypotheses using hierarchical linear modeling. These conditions are investigated through a series of models. First,

the purpose of this study is to investigate whether employee commitment is associated with

individual-level (trust-in-management and perceived organizational support) and organizational-level (human resource practices) variables. Therefore, the first condition to be established is the existence of within- (individual) and between- (organizational) variance in

employee commitment. This condition is evaluated by estimating the “null model,” which

partitions the variance in commitment into within and between-group components. A x2 test

on the residual variance indicates whether the level-2 (between-group) variance is significantly different from zero.

The second model investigates the nature of the between-group variance, after controlling

for within-group variance. For example, this model explores the amount of variance in

groups’ intercepts and slopes of the regression equations representing the relationship

between the individual-level variables, organizational commitment, and perceived organizational support. A t test of the parameters in the level 1 equation provides evidence of the

strength of the relationship between organizational commitment and perceived organizational support. A x2 test for the residual variances in the level 2 equations in which group

intercepts and slopes are regressed on unit vectors (no predictors) indicates whether the

variances in group intercepts and slopes are significantly different from zero.

Finally, the last set of models is only investigated if the second model indicates that there

is significant variance in the intercepts and/or slopes. If there is significant variance in the

intercepts, then the “intercepts-as-outcomes” model estimates whether this variance is

associated with the organizational-level variable (human resource practices). For example,

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

526

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

the level 1 equation regresses organizational commitment on perceived organizational

support as in the second model above, but the level 2 analysis of intercepts-as-outcomes adds

human resource practices as predictors to the intercept equation. The t tests on the coefficients associated with human resource practices test whether they are significantly related to

the variance in intercepts or in other words, whether human resource practices are related to

organizational commitment after controlling for perceived organizational support. If the x2

test on the residual variance is significant, it indicates that additional group-level predictors

may be associated with the group-level variance in intercepts

Similarly, if the results of the second model indicate that there is significant variance in

the slopes, then the “slopes-as-outcomes” model estimates whether this variance is associated with the organizational-level variable (tests of Hypotheses 5 and 6). This model is

similar to the intercepts-as-outcome model but adds human resource practices as a predictor

to the slopes equation in the level-2 analysis. The ttest on human resource practices indicates

whether they are significantly related to the variance in slopes. Such a result is consistent, for

example, with the notion that human resource practices affect the relationship with organizational commitment and perceived organizational support thus representing a cross-level

interaction effect. The \2 test indicates whether additional level-2 predictors might be

associated with the variance in slopes.

Hierarchical linear modeling provides several “centering” options to assist in the

interpretation of results concerning the intercept term in the level-2 analyses (Bryk &

Raudenbush, 1992; Hofmann, 1997; Hofmann & Gavin, 1998). “Grand-mean” centering

indicates that the intercept represents expected commitment for a person with an average

level of the predictor, perceived organizational support. “Group-mean” centering represents

expected commitment for a person with his or her group’s average perceived organizational

support. The appropriate choice of centering depends on the model. Grand-mean centering

provides better estimates and interpretability with most models; however, group-mean

centering plus the addition of an aggregate measure of the mean of the individual scores in

perceived organizational support in each organization, facilitates estimation and

interpretability of cross-level moderation effects (as in the slopes-as-outcomes model).

The data used for the hierarchical linear modeling analyses were gathered from over 180

credit unions with a median of 10 employees from each. Recent studies have provided

evidence that this data set should have sufficient power to detect differences. For example,

results indicate that a sample of 150 groups requires only five persons per group to obtain a

power of 0.90 (Hofmann, 1997). This data set surpasses this estimate.

Even though ten subjects per group may be adequate for power analyses, they may not

adequately represent a group. To establish whether recognizing them as a group is

appropriate, I calculated intraclass correlations and inter-rater agreement indices to examine

within-group agreement and between-group variation (James, Demaree & Wolf, 1984; Klein

& Kozlowski, 2000). ICC(1) ranged from 0.18 to 0.19, ICC(2) ranged from 0.69 to 70, and r

ranged from 0.91-0.93 indicating aggregating the measures of employee commitment,

perceptions of organizational support, and trust to the organizational level was appropriate.

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

527

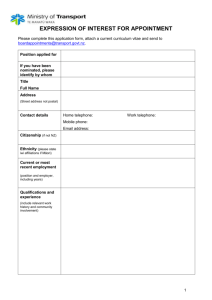

Table 1

Descriptive statisticsa

Mean SD 1

1. Perceived organizational

support

2. Trust

3. Organizational commitment

4. Appraisal

5. External rewards

6. Internal rewards

7. Staffing

8. Training

2

3

4

5

6

78

(.85)

.61**

.13

.08

.21**

.06

.01

(.90)

.10

.08

.11

.07

.09

(.78)

.16*

.37**

.35**

.42**

(.74)

.37**

.17*

.25**

(.70)

.34**

.23**

(.70)

.47* (.86)

3.60 .83 (.88)

3.86

3.96

3.01

3.65

3.41

3.72

3.34

.87

.85

.80

.73

.68

.54

.90

.66**

.70**

.20**

.12

.19**

.05

.02

an = 180 for inter-correlations among HR practices and cross-level correlations between HR practices and

aggregated employee attitudes; n = 1689 for inter-correlations among individual-level employee attitudes.

Coefficient alphas are on diagonal.

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

6. Results

Table 1 contains descriptive statistics across all levels. The individual level data allow for

the assessment of Hypotheses 1 through 3, which predict significant relationships among the

three attitudes: perceived organizational support, trust, and organizational commitment. The

correlations among these variables, presented in the top third of Table 1, indicate that the data

are consistent with these hypotheses. The relationships are strong, for example, the correlation between perceived organizational support and organizational commitment is 0.70,

consistent with results found in prior studies.

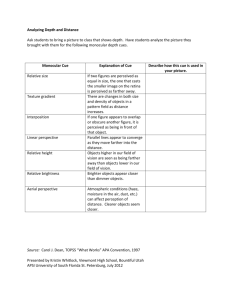

In Hypothesis 4, I predicted that trust mediates the relationship between perceived

organizational support and organizational commitment such that perceived organizational

support is both directly and indirectly related (through trust) to organizational commitment.

Table 2 presents the results of the hierarchical regression testing whether trust acts as a

mediator. The result is consistent with this prediction. The significant relationship between

perceived organizational support and organizational commitment declines substantially when

trust is added to the equation. However, the relationship between perceived organizational

support and organizational commitment remains significant when controlling for trust,

Table 2

Results of regressing employee commitment on perceived organizational support and trust (n = 1689)

Step

Independent variable

Perceived organizational

support

Perceived organizational

support

Trust

13

Adj. R2

.70

.49

.53

.53

A.R2 Fp

1658.69

.000

963.77

.000

137.67

.000

.26

.04

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

528

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

consistent with the hypothesis, that trust only partially mediates the relationship between

perceived organizational support and organizational commitment.

I investigated the cross-level hypotheses (5-7) using hierarchical linear modeling. However, before testing the hypotheses I needed to explore the conditions associated with

hierarchical linear modeling. The first condition, whether there is systematic within- and

between-group variance, is explored by looking at the null model. The x2 test on the null

model (x2 = 377.85, df. = 179, p < .001) indicated that employee commitment varied

significantly by organizations, satisfying the first condition. In addition, the intraclass

correlation (Hofmann, 1997) indicated that 10.5% of the variance in organizational commitment lies between organizations.

Similarly, the null model for trust indicated that there is systematic within and betweengroup variance. The x2 test (j(2 = 331.96, df. = 179, p < .001) showed that trust varied

significantly by organizations. The intraclass correlation (Hofmann, 1997) indicated that

8.2% of the variance in trust lies between organizations.

The second model estimated the between-group variance in the intercepts and slopes and

the amount of variance in organizational commitment or trust explained by perceived

organizational support (R 2). The results for organizational commitment replicate the findings

of previous studies indicating that organizational commitment and perceived organizational

support are strongly related (7 = 0.70, t = 33.58, p < .001; R 2 = 0.49). They also indicate

that, after controlling for perceived organizational support, sufficient variance remains in the

intercepts and slopes to investigate their relationship with human resource practices (j(2 =

273.45, df. = 179, p < .001 for intercepts; x2 = 230.69, df. = 179, p < .001 for slopes),

satisfying the second condition.

The results also indicate that perceived organizational support and trust are significantly

related (7 = 0.70, t = 31.86 p < .001; R 2 = 0.44). They reveal that, after controlling for

perceived organizational support, sufficient variance remains in the intercepts and slopes to

investigate their relationship with human resource practices (j(2 = 263.54, df. = 179, p <

.001) for intercepts; x2 = 247.75, df. = 179, p < .001 for slopes).

The intercepts-as-outcomes model explores whether human resource practices were associated with the variance in intercepts in organizational commitment or trust-in-management after controlling for perceived organizational support. t tests indicated that none of the

regression coefficients representing the relationship between human resource practices and

organizational commitment were significant. Human resource practices did not explain

additional variance in organizational commitment after controlling for perceived organizational support. However, sufficient between-group variance remained in organizational

commitment after controlling for perceived organizational support that a search for alternative between-group predictors would be warranted.

I also used the intercepts-as-outcomes model to explore whether human resource practices

were associated with the variance in intercepts in trust after controlling for perceived

organizational support. t tests indicated the coefficient representing the relationship between

internal equity of rewards and trust was significant (7 = 0.06, t = 2.05 p < .001; R 2 = 0.08).

Fairness of rewards predicts variance in trust beyond that explained by perceived organizational support. Sufficient between-group variance remained to warrant a search for additional

between-group predictors.

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

E.M. Whitener /Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

529

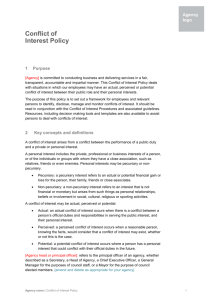

Table 3

Results of the level-2 analysis for slopes-as-outcomes (controlling for perceived organizational support)

Dependent

variable

Organizational

Commitment

Trust

y

S.E.

p

y

S.E.

p

Appraisal

External

rewards

Internal

rewards

Staffing

Training

.04

.03

.209

.07

.03

.045

— .06

.03

.054

— .05

.03

.157

.08

.04

.025

.05

.04

.216

— .04

.05

.421

.00

.05

.949

— .03

.03

.364

— .06

.03

.047

After exploring these conditions, I used the slopes-as-outcomes model to test Hypotheses

5 and 6. First I tested Hypothesis 5, whether human resource practices were associated with

the variance in slopes in organizational commitment after controlling for perceived

organizational support. Perceived organizational support was added in the level-1 equation

with group-mean centering and organizational means of perceived organizational support

were added in the intercept equation in the level-2 analysis (Hofmann & Gavin, 1998). As

shown in Table 3, t tests indicated that internal equity significantly affects the relationship

between perceived organizational support and organizational commitment such that it is

stronger when organizations have high internal equity of rewards. It accounted for 16% of

the variance in the organizational commitment—perceived organizational support slopes.

The \2 indicated that a search for additional between-group predictors would be warranted.

Second, I explored Hypothesis 6, whether human resource practices were associated with

the variance in slopes in trust after controlling for perceived organizational support. Similar

to the previous analysis, perceived organizational support was added in the level-1 equation

with group-mean centering and organizational means of perceived organizational support

were added in the intercept equation in the level-2 analysis (Hofmann & Gavin, 1998). As

shown in Table 3, t tests indicated that the interactions of developmental appraisal and

comprehensive training with perceived organizational support were related to trust. The

relationship between perceived organizational support and trust is stronger in organizations

with highly developmental appraisal processes but weaker in organizations with highly

comprehensive training opportunities. These human resource practices accounted for 23.5%

of the variance in the trust—perceived organizational support slopes. The x2 indicated that a

search for additional between-group predictors would be warranted.

Finally, the hierarchical linear modeling analyses summarized in Table 3 provide evidence

of Hypothesis 7, that appraisal and rewards processes are more likely to be associated with

commitment and trust than selection and training. The results are only partially supportive of

this hypothesis. Appraisal and internal reward human resource practices moderated the

relationships of perceived organizational support with organizational commitment or trust.

However, comprehensive training also moderated the relationship between perceived organizational support and trust (albeit in an unpredicted, negative direction).

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

530

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

7. Discussion

The purpose of the study was to explore the relationships among human resource

practices, trust-in-management, and organizational commitment using social exchange theory. Research on social exchange theory has shown that employees’ commitment to the

organization derives from their perceptions of the employers’ commitment to and support of

them. It also implies that employees interpret human resource practices and the trustworthiness of management as indicative of the personified organization’s commitment to them.

They reciprocate their perceptions accordingly in their own commitment to the organization.

Human resource practices and trustworthiness of management exist at different levels of

analysis, organizational and individual respectively, and thus require cross-level analyses.

Hierarchical linear modeling complemented analyses conducted at the individual level using

hierarchical multiple regression to investigate these relationships.

The first set of Hypotheses (1–4) summarized relationships among the individual-level

variables culminating in the integrating prediction (reflected in Hypothesis 4) that trust

partially mediates the relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational commitment (e.g., Eisenberger et al., 1990; Settoon et al., 1996). The results of the

hierarchical linear regression were consistent with a case of partial mediation: perceived

organizational support has direct and indirect relationships, through trust-in-management,

with organizational commitment.

These results indicate that employees’ trust and commitment are stronger when they

perceive that the organization is committed to and supportive of them. Researchers exploring

employees’ perceptions of organizational support have proposed such relationships but rarely

explored them empirically. This study contributes to that literature by demonstrating the

strong relationships. However, as a cross-sectional study, it cannot more deeply contribute to

the understanding of the processes of social exchange. As Blau predicted (Blau, 1964), trust

(also commitment) grows as partners’ exchanges gradually expand. To more fully investigate

these relationships, we need to conduct longitudinal studies with multiple measurements of

perceptions and attitudes.

The second set of Hypotheses (5–7) explored the cross-level relationships between human

resource practices (an organizational-level variable) and employee perceptions and attitudes

(individual-level variables). Using hierarchical linear modeling, I explored whether employees’ attitudes (trust and commitment) were related to the organization’s human resource

practices. The analysis first established that 8% of the variance in employee trust and 10%

of the variance in commitment were associated with organizational differences. Second, it

indicated that a search for organizational-level predictors was warranted for both trust and

commitment but that only internal equity of rewards directly accounted for differences across

organizations in trust after controlling for perceived organizational support.

Finally, I used hierarchical linear modeling to explore the cross-level hypotheses. The

hypotheses represented the social exchange-based notion that employees’ attitudes reflect

their interpretation of the actions of the personified organization, including the organization’s

human resource policies. In the most specific and integrated Hypothesis (7), I predicted that

appraisal and compensation activities interact with perceived organizational support to affect

both organizational commitment and trust. The results of the analyses are partially consistent

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

531

with these predictions. Two of six predicted relationships were significant: the relationship

between perceived organizational support and organizational commitment was stronger

when organizations have high internal equity of rewards and the relationship between

perceived organizational support and trust in management was stronger when organizations

conduct developmental appraisals. I also did not find evidence to reject three of the four null

predictions (for selection and training); however, contrary to expectations, training did have

a significant, and negative, interaction with perceived organizational support. Specifically,

the relationship between perceived organizational support and trust was stronger when

organizations offer less comprehensive training opportunities.

The results of the cross-level analyses are not inconsistent with Ostroff and Bowen’s

(2000) framework suggesting that human resource practices are significantly associated with

employee perceptions and employee attitudes. Organizations’ employee groups do vary in

their attitudes—differences in organizational membership were significantly associated with

differences in trust and commitment. In addition, motivation-focused human resource practices such as developmental appraisals and equitable rewards seem to have a stronger and

more meaningful relationship with those organizational differences than selection and training. Though not representing strong effects, the results indicate that managers can be

encouraged that their commitment-oriented actions are associated with positive perceptions

and attitudes.

However, the study also yielded an unexpected result—that commitment is related to a

disordinal interaction between training and perceived organizational support. The graph of

this result indicates employees with low perceptions of organizational support expressed

higher commitment when they worked for organizations with more comprehensive training

but employees with high perceptions of organizational support expressed high commitment

when they worked for organizations with less comprehensive training. The complexities of

this result suggest that other, unmeasured variables, perhaps related to employees’ perception

of special treatment might also be interacting with perceptions of support and training

comprehensiveness in affecting commitment. For example, employees in organizations with

numerous opportunities for training may not see those opportunities as conveying the

organization’s support and commitment to them personally because the opportunity and

benefit of training are widely available. And, employees in organizations with fewer opportunities for training may see these relatively rare opportunities as special treatment that

conveys the organization’s personal support and commitment.

This result needs to be explored further to see if it is an idiosyncratic result. In similar

fashion to Mayer and Davis (1999), future researchers exploring these relationships should

measure employees’ perceptions of the characteristics of human resource practices as an

intervening variable between managers’ descriptions of human resource practices and employees’ perceptions of support.

In addition, this study addresses but does not resolve the dilemma over whether human

resource practices contribute to organizations’ effectiveness as individual practices or as

systems of high commitment versus high control practices (Delery, 1998). In this study,

specific practices (e.g., internal equity of rewards and developmental performance appraisal)

were associated with a specific employee-centered outcome—employee commitment. In

other studies, systems of practices have been associated with more global measures such as

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

532

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

financial performance. These results provide some support for Delery’s proposal that the

relationship between human resource practices and outcomes depends on the fit between the

practices and outcomes—a proposal, however, that needs to be tested more directly and

deliberately.

Finally, this study has several strengths, for example, sufficient power and multiple

sources of data; however, its limitations suggest that the findings should be interpreted with

caution. First, common method variance might inflate the estimates of the strength of the

relationships among the individual-level variables (Harris & Schaubroeck, 1990). However,

because the confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the variables were sufficiently distinct

(Hinkin, 1995) and the intercorrelations were consistent with previous results, this threat is

probably minimal. Second, the data on human resource practices were provided by only one

source. The reliability and validity of this person’s perceptions of the credit union’s human

resource practices could not be verified. Third, I could not ensure managers randomly

selected employee respondents. Sampling bias could have artificially influenced the within

group agreement, reducing the variation among employees within each organization. Finally,

the domain of high commitment human resource practices includes a wide variety of

management and human resource activities. The survey measures do not include all possible

activities, policies, and procedures.

Future research should remedy these deficiencies. In addition, it should be designed to

capitalize on the analytic capabilities offered by hierarchical linear modeling to investigate

the relationship between organizational-level practices and employee attitudes and behavior.

This study explored only a few relationships but demonstrated the usefulness of hierarchical

linear modeling in testing cross-level relationships. For example, none of the correlations

between human resource practices and aggregated organizational commitment was significant; but hierarchical linear modeling analyses indicated that employees’ commitment varied

by organization and that human resource practices were associated with some of that

between-organization variation. Finally, future research should continue to explore whether

human resource practices affect organizational variables synergistically (e.g., in a bundle) or

independently.

In conclusion, employees interpret human resource practices and the trustworthiness of

management (Eisenberger et al., 1990; Settoon et al., 1996) as indicative of the personified

organization’s commitment to them. The results of this study, consistent with social exchange theory, implies that they reciprocate their perceptions accordingly in their own

commitment to the organization.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this study was presented at the 1998 Meeting of the Southern

Management Association. Thank you to David Hofmann and Jeff Vancouver for their

assistance with hierarchical linear modeling and to John Delery, Adelaide Wilcox King, and

three anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier drafts. Thanks also to the Filene

Research Institute, the Center for Credit Union Research at the University of Wisconsin—

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

533

Madison, and the Center for Financial Services Studies at the University of Virginia for their

support of this project.

Ellen M. Whitener is a professor of management at the University of Virginia’s McIntire

School of Commerce. She earned her Ph.D. in management at Michigan State University.

Her current research interest focuses on the impact of human resource practices on employee

commitment, trust, and perceptions of organizational support.

References

Allen, M. W. (1992). Communication and organizational commitment: perceived organizational support as a

mediating factor. Communication Quarterly, 40, 357-367. Arthur, J. B. (1994). Effects of human resource

systems on manufacturing performance and turnover. Academy

of Management Journal, 37, 670-687. Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable

distinction in social psychological

research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

51, 1173-1182. Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life.

New York: Wiley.

Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical linear models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Delaney, J. T.,

& Huselid, M. A. (1996). The impact of human resource management practices on perceptions of

organizational performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 949-969. Delery, J. E. (1998). Issues of fit

in strategic human resource management: implications for research. Human

Resource Management Review, 8, 289-309. Eisenberger, R., Fasolo, P., & Davis-LaMastro, V. (1990).

Perceived organizational support and employee

diligence, commitment, and innovation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 51-59. Eisenberger, R.,

Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 71, 500-507. Folger, R., & Konovsky, M. (1989). Effects of procedural and distributive

justice on reactions to pay raise

decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 115-130. Gopinath, C, & Becker, T. E. (2000).

Communication, procedural justice, and employee attitudes: relationships

under conditions of divestiture. Journal of Management, 26, 63-83. Guzzo, R. A., Noonan, K. A., & Elron, E.

(1994). Expatriate managers and the psychological contract. Journal

of Applied Psychology, 79, 617-626. Harris, M. M., & Schaubroeck, J. (1990). Confirmatory modeling in

organizational behavior/human resource

management: issues and applications. Journal of Management, 16, 337-360. Hinkin, T. R. (1995). A review of

scale development practices in the study of organizations. Journal of

Management, 21, 967-988. Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in

survey questionnaires.

Organizational Research Methods, 1, 104-121. Hofmann, D. A. (1997). An overview of the logic and rationale

of hierarchical linear models. Journal of

Management, 23, 723-744. Hofmann, D. A., & Gavin, M. B. (1998). Centering decisions in hierarchical linear

models: implications for

research in organizations. Journal of Management, 24, 623-641. Hofmann, D. A., Griffin, M. A., & Gavin, M.

B. (2000). The application of hierarchical linear modeling to

organizational research. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods

in organizations: foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 467-511). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World. House, R., Rousseau, D. M.,

Thomas-Hunt, M. (1995). The meso paradigm: a framework for the integration of

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

534

E.M. Whitener / Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515–535

micro and macro organizational behavior. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational

behavior (pp. 71–114). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource

management practices on turnover, productivity, and

corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 635–672. Hutchison, S., & Garstka,

M. L. (1996). Sources of perceived organizational support: goal setting and feedback.

Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26, 1351–1366. Ichniowski, C., Shaw, K., & Prennushi, G. (1997).

The effects of human resource management practices on

productivity. American Economic Review, 87, 291–313. James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1984).

Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without

response bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 85–98. Kim, W. C., & Mauborgne, R. A. (1993). Procedural

justice, attitudes, and subsidiary top management compliance with multnationals’ corporate strategic decisions.

Academy of Management Journal, 36, 502–526. Klein, K. J., & Kozlowski, S. W. J. (2000). From micro to meso:

critical steps in conceptualizing and conducting

multilevel research. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 211–236. Levering, R., & Moskowitz, M. (2000).

100 best companies to work for in America. Fortune, January 10,

82–110. Levinson, H. (1965). Reciprocation: the relationship between man and organization. Administrative

Science

Quarterly, 9, 370 –390. Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (1999). The effect of the performance appraisal system

on trust for management:

a field quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 123–136. MacDuffie, J. P. (1995). Human

resource bundles and manufacturing performance: organizational logic and

flexible production systems in the world auto industry. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 48, 197–221.

Miceli, M. P., & Mulvey. P. W. (2000). Consequences of satisfaction with pay systems: two field studies.

Industrial Relations, 39, 62– 87. Mowday, R. T., Steers, R. M., & Porter, L. W. (1979). The measurement of

organizational commitment. Journal

of Vocational Behavior, 14, 224–247. Ostroff, C., & Bowen, D. E. (2000). Moving HR to a higher level: HR

practices and organizational effectiveness.

In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations:

foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 211–266). San Francisco: Jossey–Bass. Pearce, J. L. (1993).

Toward an organizational behavior of contract laborers: their psychological involvement and

effects on employee co-workers. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 1082–1096. Pillai, R., Schriesheim,

C. A., & Williams, E. S. (1999). Fairness perceptions and trust as mediators for

transformational and transactional leadership: a two-sample study. Journal of Management, 25, 897–933.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Bommer, W. H. (1996). Transformational leader behaviors and substitutes

for leadership as determinants of employee satisfaction, commitment, trust, and organizational citizenship

behaviors. Journal of Management, 22, 259–298. Robinson, S. L., & Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Violating the

psychological contract: not the exception but the norm.

Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15, 245–259. Rousseau, D. M. (1985). Issues of level in organizational

research: multi-level and cross-level perspectives. In

L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 1–37). Greenwich, CT: JAI

Press. Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: a crossdiscipline

view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23, 393–404. Settoon, R. P., Bennett, N., & Liden, R. C.

(1996). Social exchange in organizations: perceived organizational

support, leader-member exchange, and employee reciprocity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 219–227.

Shore, L. M., & Tetrick, L. E. (1991). A construct validity study of the Survey of Perceived Organizational

Support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 637–743. Shore, L. M., & Wayne, S. J. (1993). Commitment and

employee behavior: comparison of affective commitment

and continuance commitment with perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78,

774–780.

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010

E.M. Whitener/Journal of Management 27 (2001) 515-535

535

Snell, S., & Dean, J. (1992). Integrated manufacturing and human resource management: a human capital

perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 467-504.

Tsui, A. S., Pearce, J. L., Porter, L. W., & Tripoli, A. M. (1997). Alternative approaches to the employeeorganization relationship: does investment in employees pay off? Academy of Management Journal, 40,

1089-1121.

Walton, R. E. (1985). From control to commitment in the workplace. Harvard Business Review, 63 (2), 77-84.

Watson Wyatt. (1999). WorkUSA 2000: employee commitment and the bottom line. Bethesda, MD: Watson

Wyatt.

Wayne, S. J., Shore, M., & Liden, R. C. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange:

a social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 82-111.

Whitener, E. M. (1997). The impact of human resource activities on employee trust. Human Resource Management Review, 7, 389-404.

Wood, S., & de Menezes, L. (1998). High commitment management in the U.K.: evidence from the Workplace

Industrial Relations Survey and Employers’ Manpower and Skills Practices Survey. Human Relations, 51,

485-515.

Youndt, M., Snell, S., Dean, J., & Lepak, D. (1996). Human resource management, manufacturing strategy, and

firm performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 836-866.

Downloaded from jom.sagepub.com at Seoul National University on November 23, 2010