C. The Monastic Life_1. Eremetic Life & 2. Rule of

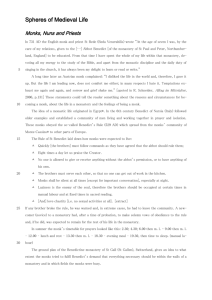

advertisement

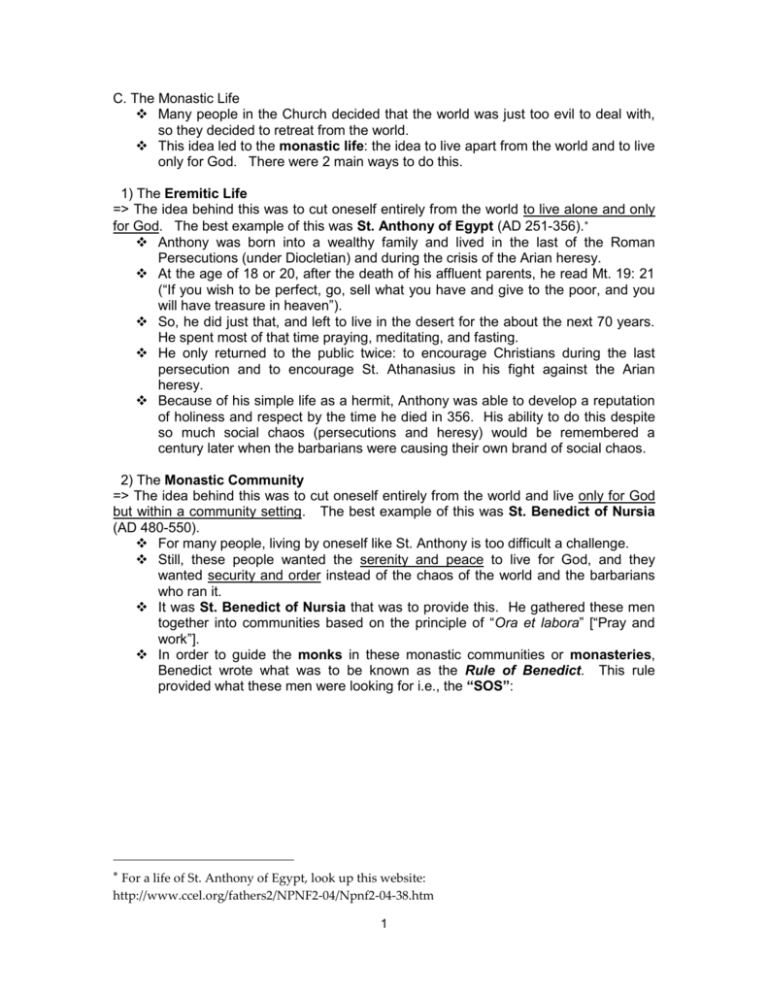

C. The Monastic Life Many people in the Church decided that the world was just too evil to deal with, so they decided to retreat from the world. This idea led to the monastic life: the idea to live apart from the world and to live only for God. There were 2 main ways to do this. 1) The Eremitic Life => The idea behind this was to cut oneself entirely from the world to live alone and only for God. The best example of this was St. Anthony of Egypt (AD 251-356). Anthony was born into a wealthy family and lived in the last of the Roman Persecutions (under Diocletian) and during the crisis of the Arian heresy. At the age of 18 or 20, after the death of his affluent parents, he read Mt. 19: 21 (“If you wish to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven”). So, he did just that, and left to live in the desert for the about the next 70 years. He spent most of that time praying, meditating, and fasting. He only returned to the public twice: to encourage Christians during the last persecution and to encourage St. Athanasius in his fight against the Arian heresy. Because of his simple life as a hermit, Anthony was able to develop a reputation of holiness and respect by the time he died in 356. His ability to do this despite so much social chaos (persecutions and heresy) would be remembered a century later when the barbarians were causing their own brand of social chaos. 2) The Monastic Community => The idea behind this was to cut oneself entirely from the world and live only for God but within a community setting. The best example of this was St. Benedict of Nursia (AD 480-550). For many people, living by oneself like St. Anthony is too difficult a challenge. Still, these people wanted the serenity and peace to live for God, and they wanted security and order instead of the chaos of the world and the barbarians who ran it. It was St. Benedict of Nursia that was to provide this. He gathered these men together into communities based on the principle of “Ora et labora” [“Pray and work”]. In order to guide the monks in these monastic communities or monasteries, Benedict wrote what was to be known as the Rule of Benedict. This rule provided what these men were looking for i.e., the “SOS”: For a life of St. Anthony of Egypt, look up this website: http://www.ccel.org/fathers2/NPNF2-04/Npnf2-04-38.htm 1 a) erenity and peace: Benedict’s Rule provided a closer relationship with God through Mass and regular prayer known as the Divine Office* (which Benedict called “God’s work”). b) rder: Daily life for the monks was practically and strictly organized, in contrast to the free-forall that the barbarians were causing. From waking up to going to bed, a monk’s schedule was consistently based on the 8 hours of the Divine Office. c) elf-sufficiency: Amid the monastic schedule, many tasks were done according to the skill level of individual monks. Some were artistically skilled—they worked on music, crafts, or art. Some had medical training—these worked in the infirmary or the herb/medicine garden. Some were intellectually inclined—they worked in the library. Most were unskilled— these monks did the menial tasks such as agricultural labour or other jobs. These soon allowed monasteries to be self sufficient and independent of the economy that was falling apart around them. Benedict’s Rule was a success, and he is credited as the Founder of Western Monasticism, which would grow to become an important element in the development of the Church. His first monastery was on the site of an old Roman temple on Monte Cassino in Italy. With the help of his sister St. Scholastica, he was able to modify his rule for women/nuns. Assignment: primary source 1. Look at the excerpts of the Rule of St. Benedict. After reading through it, find how Benedict’s Rule supplied his monks the (a) serenity and peace, (b) order, and (c) self-sufficiency. Be sure to note what chapter of the Rule you found your information, just like you would a biblical passage. [5 marks]. 2. Look at the architectural plan of the monastery of St. Gall. Use it to explain the how the plan provided the monks serenity, order, and self-sufficiency. [5 marks] The 8 Hours of the Divine Office are publicly celebrated prayers based on psalms and other readings from the Bible. The 8 hours are Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline. 2 The Holy Rule of St. Benedict (excerpts) CHAPTER IX How Many Psalms Are to Be Said at the Night Office During the winter season, having in the first place prayed the verse: Deus, in adjutorium meum intende; Domine, ad adjuvandum me festina, there is next to be said three times, Domine, labia mea aperies, et os meum annuntiabit laudem tuam [These were prayers from the Divine Office from Psalm 50[51]:17]. To this the third psalm and the Gloria [i.e., the prayer “Glory Be to the Father”] are to be added. …When these and the verse have been said, let the Abbot give the blessing…Let the inspired books of both the Old and the New Testaments be read at the night offices, as also the [studies done by]…the most [learned] Catholic Fathers… CHAPTER XX Of Reverence at Prayer If we [are humble in front of a powerful man] when we wish to ask a favor, how much more [humble ought we to be when] we ask the Lord God of all things…? And let us be assured that [what matters is not how] many words we say, but [how pure our] hearts are…For this reason prayer ought to be short and pure, unless, perhaps it is lengthened by the inspiration of divine grace... CHAPTER XXXI The Kind of Man the Cellarer of the Monastery Ought to Be Let there be chosen from the brotherhood as Cellarer of the monastery a wise man, of settled habits, temperate and frugal, not conceited, irritable, resentful, sluggish, or wasteful, but fearing God, who may be as a father to the whole brotherhood. Let him have the charge of everything, let him do nothing without the command of the Abbot, let him do what he has been told and not irritate the [rest of the brothers]. If a brother asks for anything [silly], the Cellarer should not sadden the brother with a cold refusal, but politely and with humility [say no]. Let him be watchful of his own soul, always [remembering what the Apostle Paul said}: "For they that have served well, will gain good standing" (1 Tm 3:13). Let him provide for the sick, the children, the guests, and the poor, with all care, since undoubtedly, he will have to give an account of all these things on judgment day. Let him regard all the possessions of the monastery, as if they were sacred vessels of the altar. Let him neglect nothing and let him not give way to greed, nor let him be wasteful and a squanderer of the goods of the monastery; but let him do all things in due measure and according to the bidding of his Abbot. Above all things, let him be humble; and if he has nothing to give, let him answer with a kind word, because it is written: "A good word is above the best gift" (Sir 18:17). Let him have under his charge everything that the Abbot has entrusted to him, and not presume to meddle with matters [that are not his business]. Let him give the brethren their apportioned allowance without a disturbance or delay, that they may not be scandalized, mindful of what the Gospels declare about those who shall scandalize one of these little ones: "It were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck and that he were drowned in the depth of the sea" (Mt 18:6). If the community is large, let assistants be given him, that, with their help, he too may fulfill the duty entrusted to him with an even temper. Let the things that are to be given be distributed, and the things that are to be received asked for at the proper times, so that nobody may be disturbed or grieved in the house of God. 3 CHAPTER XXXIX Of the Quantity of Food Making allowance for the [weakness] of different persons, we believe that for the daily meal, both at the sixth and the ninth hour, two kinds of cooked food are [enough] at all meals…Let two kinds of cooked food, therefore, be enough for all the brethren. And if there [are] fruit or fresh vegetables, a third [meal] may be added. Let a pound of bread be [enough] for the day, whether there be only one meal or both dinner and supper. If they are to eat supper, let a third part of the pound [of bread] be reserved by the Cellarer and be given at supper. If, however, the work has been especially hard, it is left to the discretion and power of the Abbot to add something [more], if he [thinks it necessary, making sure that nothing is done in] excess, that a monk be not overtaken by indigestion. For nothing is so contrary to Christians as excess, as our Lord said: "Beware that your hearts do not become drowsy from carousing and drunkenness." (Lk. 21:34). Let the same [amount] of food, however, not be served to young children but less than to older ones, observing [proper] measure in all things. But let all except the very weak and the sick [avoid] eating the flesh of four-footed animals [i.e., red meat]. CHAPTER XL Of the Quantity of Drink [M]aking allowance for the weakness of the sick, we think one hemina [about 10 oz] of wine a day is sufficient for each one...If the circumstances of the place, or the work, or the summer's heat should require more, let that depend on the judgment of the Superior, who must above all things see to it, that excess or drunkenness do not creep in. Although we read that wine is not at all proper for monks, yet, because monks in our times cannot be convinced of this, let us agree to this, at least, that we do not [over]drink, but sparingly; because "wine makes even wise men fall." (Sirach 19:2). But where the poverty of [some monasteries that cannot afford wine], let those who live there bless God and [complain] not. CHAPTER XLVIII Of the Daily Work [Laziness] is the enemy of the soul; and therefore the Brothers ought to be employed [either] in manual labor [or] in devout reading. Hence, we believe that the time for each will be [organized] by the following arrangement; that from Easter until [mid-October], they go out in the morning from the first hour [6 am] to the fourth hour [10 am] to do the necessary work, but that from the fourth to about the sixth hour [noon] they devote to reading. After the sixth hour [noon], however, when they have risen from table, let them rest in their beds in complete silence; or if, perhaps, anyone [wants] to read for himself let him so read that he does not disturb others. Let None [the part of the Divine Office said at 3 pm] be said somewhat earlier, about the middle of the eighth hour [2:30 pm]; and then let them work again at what is necessary until Vespers [the part of the Divine Office said at 5 pm]… 4 The plan of the 9th c. monastery of St. Gall 5