Gregory the Great

advertisement

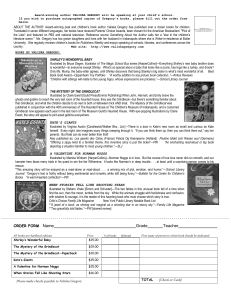

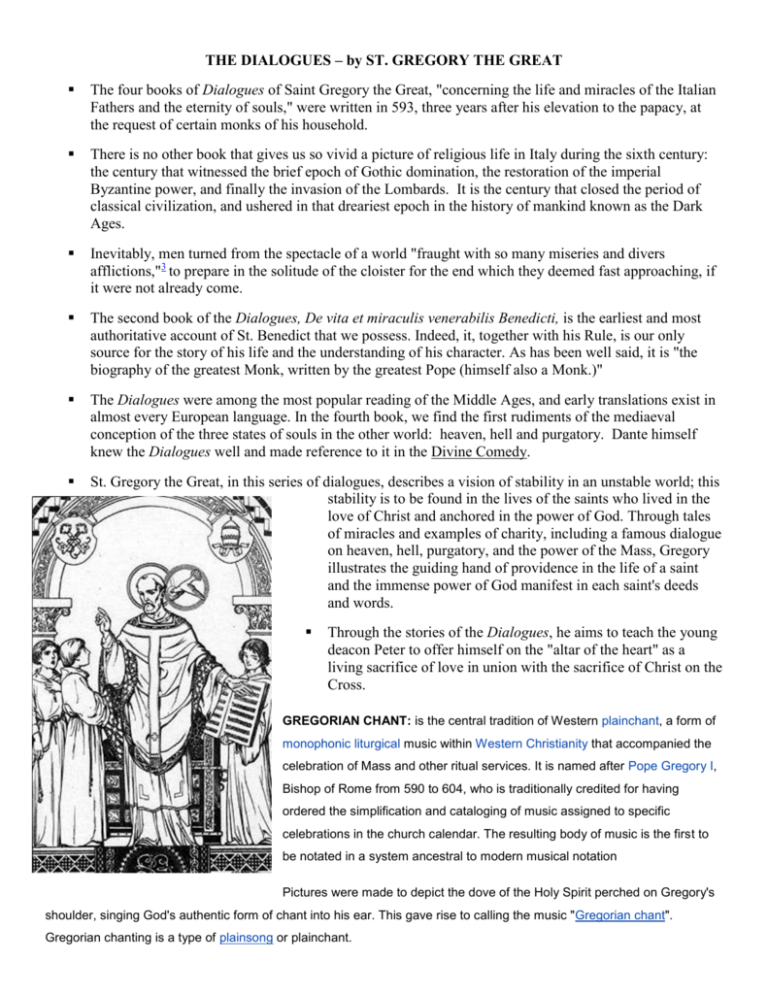

THE DIALOGUES – by ST. GREGORY THE GREAT The four books of Dialogues of Saint Gregory the Great, "concerning the life and miracles of the Italian Fathers and the eternity of souls," were written in 593, three years after his elevation to the papacy, at the request of certain monks of his household. There is no other book that gives us so vivid a picture of religious life in Italy during the sixth century: the century that witnessed the brief epoch of Gothic domination, the restoration of the imperial Byzantine power, and finally the invasion of the Lombards. It is the century that closed the period of classical civilization, and ushered in that dreariest epoch in the history of mankind known as the Dark Ages. Inevitably, men turned from the spectacle of a world "fraught with so many miseries and divers afflictions,"3 to prepare in the solitude of the cloister for the end which they deemed fast approaching, if it were not already come. The second book of the Dialogues, De vita et miraculis venerabilis Benedicti, is the earliest and most authoritative account of St. Benedict that we possess. Indeed, it, together with his Rule, is our only source for the story of his life and the understanding of his character. As has been well said, it is "the biography of the greatest Monk, written by the greatest Pope (himself also a Monk.)" The Dialogues were among the most popular reading of the Middle Ages, and early translations exist in almost every European language. In the fourth book, we find the first rudiments of the mediaeval conception of the three states of souls in the other world: heaven, hell and purgatory. Dante himself knew the Dialogues well and made reference to it in the Divine Comedy. St. Gregory the Great, in this series of dialogues, describes a vision of stability in an unstable world; this stability is to be found in the lives of the saints who lived in the love of Christ and anchored in the power of God. Through tales of miracles and examples of charity, including a famous dialogue on heaven, hell, purgatory, and the power of the Mass, Gregory illustrates the guiding hand of providence in the life of a saint and the immense power of God manifest in each saint's deeds and words. Through the stories of the Dialogues, he aims to teach the young deacon Peter to offer himself on the "altar of the heart" as a living sacrifice of love in union with the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross. GREGORIAN CHANT: is the central tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic liturgical music within Western Christianity that accompanied the celebration of Mass and other ritual services. It is named after Pope Gregory I, Bishop of Rome from 590 to 604, who is traditionally credited for having ordered the simplification and cataloging of music assigned to specific celebrations in the church calendar. The resulting body of music is the first to be notated in a system ancestral to modern musical notation Pictures were made to depict the dove of the Holy Spirit perched on Gregory's shoulder, singing God's authentic form of chant into his ear. This gave rise to calling the music "Gregorian chant". Gregorian chanting is a type of plainsong or plainchant. THE LIFE OF ST. GREGORY THE GREAT Father of the Post-Nicene Era, Pope Gregory I (c. 540 – 12 March 604), better known in English as Gregory the Great, was pope from 3 September 590 until his death. He is also known as St. Gregory the Dialogist in Eastern Orthodoxy because of his Dialogues. Gregory is well known for his writings, which were more prolific than those of any of his predecessors as pope. He was the first of the popes to come from a monastic background. Gregory is a saint and a Doctor of the Church. Immediately after his death, Gregory was canonized by popular acclaim. The exact date of Gregory's birth is uncertain, but is usually estimated to be around the year 540, in the city of Rome. Gregory had been born into a wealthy noble Roman family with close connections to the church. Gregory was well educated, with Gregory of Tours reporting that "in grammar, dialectic and rhetoric ... he was second to none...."[20] He wrote correct Latin but did not read or write Greek. He knew Latin authors, natural science, history, mathematics and music and had such a "fluency with imperial law" that he may have trained in law, it has been suggested, "as a preparation for a career in public life." Gregory's mother Silvia herself is a saint. On his father's death, he converted his family villa suburbana, located on the Caelian Hill just opposite the Circus Maximus, into a monastery dedicated to the apostle Saint Andrew. Gregory was not always forgiving, or pleasant for that matter, even in his monastic years. For example, a monk lying on his death bed confessed to stealing three gold pieces. Gregory forced the monk to die friendless and alone, then threw his body and coins on a manure heap to rot with a curse, “Take your money with you to perdition”. Gregory believed that punishment of sins can begin, even on one's deathbed. In 579, Pelagius II chose Gregory as his apocrisiarius (ambassador to the imperial court in Constantinople). Gregory left Constantinople for Rome in 585, returning to his monastery on the Caelian Hill. Gregory was elected by acclamation to succeed Pelagius II in 590, when the latter died of the plague spreading through the city. Although Gregory was resolved to retire into the monastic lifestyle of contemplation, he was unwillingly forced back into a world that, although he loved, he no longer wanted to be a part of. In texts of all genres, especially those produced in his first year as pope, Gregory bemoaned the burden of office and mourned the loss of the undisturbed life of prayer he had once enjoyed as monk. When he became Pope in 590, among his first acts was writing a series of letters disavowing any ambition to the throne of Peter and praising the contemplative life of the monks. Gregory is credited with re-energizing the Church's missionary work among the barbarian peoples of northern Europe. He is most famous for sending a mission, often called the Gregorian mission, under Augustine of Canterbury, prior of Saint Andrew's, where he had perhaps succeeded Gregory, to evangelize the pagan AngloSaxons of England. The mission was successful, and it was from England that missionaries later set out for the Netherlands and Germany. The preaching of the true Catholic faith and the elimination of all deviations from it was a key element in Gregory's worldview, and it constituted one of the major continuing policies of his pontificate. St. Gregory the Great worked to reform the Liturgy. Sacramentaries directly influenced by Gregorian reforms are referred to as Sacrementaria Gregoriana. With the appearance of these sacramentaries, the Western liturgy begins to show a characteristic that distinguishes it from Eastern liturgical traditions.