Video transcript

advertisement

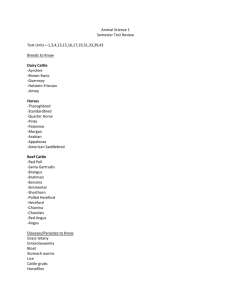

29 Bradman Tues 1600 1730 MICHAEL LYONS Today, I'd like to tell you a story about one family, two guiding principles, three secrets of profit, and how that influenced the study topics that I looked at in my Nuffield scholarship, five strategies that we're using to work with nature on our property at Charters Towers, and then to go ahead and keep with the whole numbers thing, talk about at the end about how the whole is actually more important than the sum of all those parts. So the one family that I'm going to speak about is my own family, surprise, surprise. And our story in Australia starts in 1883, when my great-grandfather at 18 years of age left Ireland in search of a better life. And in 1912, he purchased Wambiana Station, which is the station that my wife and I manage for our family business. And so we've been custodians of that land for over a century. And yes, so my parents, John and Rhonda Lyons, are the head of our business, and are pictured here with their grandchildren, who are the fifth generation of the family to work on the property. My siblings are all involved in the beef industry and have worked in and out of the business. We operate three cattle stations around the Charters Towers district and a small supermarket in Charters Towers. Wambiana itself is 23,000 hectares. It has a range of country from some lighter silverleaf on back country through to some heavier [INAUDIBLE] shrubs. We run 300,000 to 350,000 head of cattle across a range of enterprises, from breeding and selling bulls to growing out steers, trading cattle, and taking on adjustment. My family and I feel a real affinity to Wambiana and the animals that we manage on the property. We're also well aware that we stand on the shoulders of previous generations of risk takers and courageous hard workers. It's great having that history-- and Jason alluded to it, as well-- but history doesn't pay bills. And so we're always looking for innovations to improve our business. We believe in balance. And the two guiding principles that we feel are important in a grazing business are to be economically profitable but you also have to be ecologically sustainable. Being too focused on one or the other won't build a truly sustainable business. And fortunately, I think there are strategies that can accommodate both. So let's start with profit. We talk a lot about profit in agriculture and I sometimes wonder for people outside the industry whether they think that we're greedy in wanting more and more profit. But I think that's not the case at all. The reality is, for the northern beef industry, that profitability is difficult to achieve. Meat & Livestock Australia's Northern Beef Report from 2013 indicated that the northern beef industry return on assets managed over the 12 years has averaged less than 1% per year. And if you couple this with some of the high debt levels, you can understand why there's so much hurt in the northern industry. Before returning to work in the family business and as a new graduate in agricultural science, I worked with Terry McCosker at RCS in Yeppoon. And I was amazed to learn about the three secrets of improving profitability. So the first one is that we can reduce our overheads. Some of our land and labour costs are there irrespective of our enterprise, but we have to be careful that we don't reduce those so much that we starve a profit into our business. We can also look at increasing gross margins. And we can do this in probably three key ways. We can increase the price received, we can increase our productivity, or we can reduce our direct costs. And the third one is to increase turnover. So if we've got a positive gross margin, that how do we scale up or increase the throughput through turnover? So I was keen to look for opportunities to improve profitability for the northern industry. And last year, I was fortunate to receive a Nuffield scholarship and sincerely thank Meat & Livestock Australia, who sponsored me in that process. It has been an amazing adventure. So after travelling through the countries that Rich was talking about earlier, what did I find? One of the key areas I was interested in was looking into selection of fertile and environmentallyadapted cattle. And this was driven by the appeal of getting good production with low input costs. And that is like increasing that gross margin. And so what I learnt was that genetic selection is happening whether we plan for it or not, so we'd better select what we do want. If we introduce a bull into our herd with undesirable traits, it will impact their business or that herd for the next 15 years. It's highlighted to me the need to performance record herds in a lot more detail. We need to measure, record, use that information for careful selection, and then cull the non-performers. I was amazed by a visit to Jacarezinho in Brazil, where that particular farm is part of the Delta G group that are performance-recording 80,000 female cattle annually and only selecting their bulls from the top 10% of the performers. They only keep them for one year because the next year, that new crop will be far better. This progressive meat producers in the USA and Brazil are using selection indexes for selecting bulls, rather than just single traits. They give weightings to various traits depending on the importance of that trait to their environment or what they're aiming to produce. And I think the Angus Association is doing a great job here, too, with our selection indices. The next area I thought was very important is there's no use having the good genetics if we can't express those with good nutrition. And so to me, grazing management systems are also important, and particularly on how to manage pastures to achieve the maximum sustainable production per hectare. So this is about increasing turnover and decreasing our overheads per head. And the key message I found there was that the most important thing is to manage ground cover. Degradation occurs when we don't maintain ground cover. And surprise, surprise, when we have good ground cover, we increase the vigour of our plants and we increase biodiversity. So I looked at cell grazing, Serengeti grazing, ultra high density grazing-- and I think all of these things have got really positive impacts. But again, the common thread was about utilising pasture in a controlled manner, returning nutrients to the soil, and then allowing sufficient rest for pastures to recover. The next area that I had interest in was polled genetics and that's breeding cattle that naturally don't have horns. I believe polled cattle will be the way of the future, due to the better animal welfare and prevention of losses from dehorning and so contributing to better gross margins. I determined that there were two pathways to polledness or to increase the number of polls in our herds. And one is to select within your breed for the animals that are polled and the other is to cross-breed with another polled breed. In terms of cross-breeding, I was interested in some of the adapted Bos taurus breeds from similar environments in Africa and the Caribbean, such as the Mashona and Centre Poll. These breeds offer polledness but also hybrid vigour. I also looked into the Brahman breed, as well, because that's where our interest was, mainly because it keeps our system very simple, and with less mobs of cattle, allows us to do more in their area of rotational grazing. I think the horn poll test in Australia is great for determining which bulls are homozygous for the poll gene. This is a dominant gene, so when you cross a homozygous bull over a horned cow, all of the progeny will be polled. And kudos again to MLA, who are instrumental in providing funding for R&D to set up that test that now is for us as producers as simple as pulling a hair sample and sending it to a lab. And the final area that I was interested in was complementary enterprises. And my question here was, what other enterprises could we operate in conjunction with running cattle that would allow us to spread our overheads and create a high gross margin enterprise? The diversified businesses that I visited tended to do one of two things. They either diversified into a brand-new enterprise, such as running crayfish with cattle-- not in the same pond-- or they would intensify their existing operation. So if they were running cattle, they may then add a feedlot or direct market their product. The key thing seemed to be that these people looked for underutilised resources in their business or they looked for a resource that was leaking out and they weren't capturing the value from it. The master of this was Joel Salatin from Virginia in the USA, who Time Magazine refers to as "the world's most innovative farmer." Joel has combined enterprises from pastured pigs, chickens, and cattle, rabbits, grows vegetables, processes all those animals and vegetables, and then direct markets all of his produce. He doesn't waste anything. So overall, my travels confirmed for me that there were no silver bullets. However, visiting these successful businesses confirmed that working with nature as much as possible lowers costs, is good for the environment, and is good for business. And so that then leads me to five strategies that we're looking at or that we are trying on our property at Charters Towers. So we have fenced off our riparian areas, subdivided paddocks, and spread out our water points so that our cattle don't have to walk more than one and a 1/2 kilometres to get a drink of water. This allows us to better manage our postures through grazing and resting and also by spreading the grazing pressure over the whole property. We control mate our cows so that our calves are born just prior to the start of the wet season and in good body condition score. That way, that as the calf grows and demands more milk from its mother, the cow has the ability to produce that milk but also her reproductive system is healthy and she can fall pregnant while lactating to produce a calf for the next year. We run about 100 camels on the property, which were introduced to control the weed Parkinsonia. So rather than spend thousands of dollars on chemical every year to control the plants, the camels do a great job of stripping the leaves, flowers, and seedpods off the Parkinsonia and prevent it from spreading. We also host groups of students for outback experiences, up to 1,000 students per year in groups, which allows us to utilise our natural resources as teaching tools and utilise our people resources to generate other forms of income irrespective of cattle prices and rainfall. We host local primary school students, American high school ambassadors, and local and international university students. And we also lease 1,000 hectares of land to DAFF Queensland for a long-term grazing trial. The Wambiana grazing trial has been running for 17 years and is helping to link pasture composition, animal production, and economics to assess the different grazing systems' resilience to the variable rainfall and climate that we live in. Now, I'd like to point out that of all those five strategies, any one of them isn't going to make a huge difference to your business. But the power comes from looking at the whole, our business, our people, our land, and our livestock. And then, make changes, no matter how small, that start heading you towards your preferred direction. In no time at all, one plus one plus one can start to equal five or 10 or 15 as the synergies of those actions move you forward. And I'd like to just give you one example of that. One of our latest projects used IVF to multiply some fertile adapted genetics. We purchased cows from CSIRO when they closed Belmont Research Station like this cow here, that have produced 10 calves in 10 years naturally and in a northern environment, which is a great feat in our part of the world. I spoke about selection indexes earlier. Well, the Jap Ox index for the Brahman breed takes into account estimated breeding values for fertility, growth, and carcass characteristics. The average value for the Brahman breed is plus 22. This cow, at plus 52, is in the top 5% of the breed. She possesses the sort of genetics that we need. So we decided to do an IVF programme to increase the number of progeny, because at 13 years of age, she was unlikely to have many more calves. Using the same selection index, we selected semen from bulls including this one that has a Jap Ox index of plus 50, which places him in the top 5% of the breed also. But he comes with an added bonus. He's been horn poll tested and is homozygous polled. So we know before we even start the programme that every calf will be polled. We worked with a group of Brazilian vets from Adventure Genetics to fertilise these eggs and then transfer them into our own Brahman cows that had been pregnancy-tested non-pregnant. The result of this process using 10 donor cows and semen from two bulls was 51 live calves that are all polled with excellent genetics and will be adapted to our environment, raised in our environment, by cows that know our country. So this project ties together many of the things that I've spoken about today. We have taken cows that nature has tested and proved that they are fertile and adapted, augmented this with technology, such as using the selection indexes, poll gene testing, and IVF-- we've tapped into an unutilised resource being our non-pregnant cows to be the recipients and raise the embryos. And those recipients are raising those calves at the moment and they're being remated naturally. And I think a lot of them will fall pregnant again to produce a calf next year. And so what a good use of the grass resource we have available, particularly in a year like this where we're quite dry. And while this is just one example, I think this type of holistic, integrated thinking and working with nature offers a profitable future for northern beef producers. And so this is my final slide. And many of you will recognise the symbol as the power button on your electrical appliances, like your TV or a computer, with a green twist. Now, when you go to turn on your computer, you actually have to press the button. You need to commit to it or else it doesn't happen. And so, too, with changes in our businesses. As William Hutchison Murray puts it, "Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the opportunity to back out, always ineffectiveness. But the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves also. All sorts of things occur to help you that would have never otherwise occurred. A whole stream of events issues from that decision, raising in your favour or manner of unforeseen incidents, meetings, and material assistance which no man could have dreamed of would come your way. Whatever you do or dream you can do, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it." Thank you.