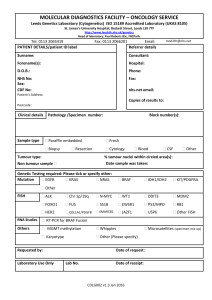

Detect Cancer Early Programme

advertisement