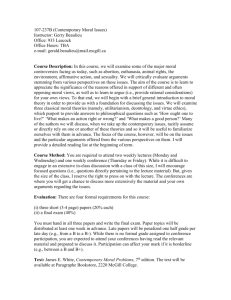

Moral Potency

advertisement