Acts 7`54-60 2015 - North Central Christian Church

advertisement

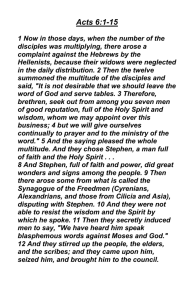

1 The Cure for IED A Sermon on Acts 7:54-60 By Don Tuttle, senior pastor North Central Christian Church, San Antonio, Texas Preached July 5, 2015 Lt. Commander Dan Grimsbo, now retired, spent a year working in and around Bagdad in ’06 and ’07. When he returned to Corpus Christi, he made a presentation to our congregation about the work being done there. As part of his presentation he shared a brief video one of his colleagues had taken. The video showed several soldiers scanning their surroundings and chatting as their convoy headed north out of Bagdad. All was well until suddenly a huge blast erupted just to the right of the road. It rocked the Humvee in front of him and propelled dirt, debris and smoke far into the air. One soldier was caught on tape uttering an exclamation appropriate for the moment but unfit for polite company. As you might have guessed, the convoy had triggered an IED—an Improvised Explosive Device. Such bombs were the weapon of choice among insurgents in Iraq and Afghanistan as well as among terrorists groups like Hamas, so much so that I would imagine that all of us are now familiar with the term. Yet there is another IED of which you might not be aware. It is not as deadly as those being used in Iraq, but it is much more common and still quite destructive. This IED is “Intermittent Explosive Disorder.” According to the Mayo Clinic, “Intermittent Explosive Disorder is characterized by repeated episodes of aggressive, violent behavior that are grossly out of proportion to the situation.” Those suffering from it “may attack others and their possessions, causing bodily injury and property damage,” about which “they later may feel remorse, regret or embarrassment.” According to The National Institute of Mental Health, more than 7 percent of us suffer from IED. While I imagine that figure is as good as any such estimate, anecdotal evidence suggests IED might be more widespread. It is just called by another name—rage. A couple of weeks ago, two cars nearly collided as one merged onto Highway 90 West. One of the drivers was none too pleased, and so he pulled alongside the other man’s car and began throwing items at it. And when the man pulled off the highway, the angry driver followed. He got out of his car, broke the man’s window, and then beat the man severely enough that he needed stitches and staples. It was, police said, a case of road rage. Some people got into an argument outside a San Antonio bar last weekend. One of them, a woman, got into her car and ran over three people on her way out, sending at least one to the hospital. Then Monday evening a couple of employees from a rent-to-own store showed up at a local home to repossess some furniture. The became enraged, grabbed a machete, and took after the pair. One of them suffered a cut to his arm. But IED isn’t limited to unhappy San Antonians—or tragic but relatively limited damage. We have seen it on a larger scale, haven’t we? It was only 10 months ago that a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, stopped a couple of young men walking in the street. The stop escalated when one of the men attacked the 2 officer and ended when the young man was shot to death. What followed could well be described as a case of Intermittent Explosive Disorder. In the weeks that followed violent protests sporadically erupted. Dozens of business were looted, vandalized or burned down as well as numerous vehicles, including a couple of patrol cars. And, of course, in April we saw a similar scene in Baltimore, Maryland. That’s when a 25-year-old man sustained injuries following his arrest and died a few days later. When his death was ruled a homicide, protests began. In the days that followed, rioters damaged more than 200 small businesses and a like number of cars. While it’s important not to minimize the tragic events that triggered these riots, all of them might be rooted in Intermittent Explosive Disorder. People exploded in anger, attacked other people and other people’s property, all out of proportion to the situation. And, I suspect, many came to regret the damage they did. They, like others, are an example of what one author calls “the age of rage.” Fortunately, IED is not incurable. Christianity offers an antidote. Whether we call it Intermittent Explosive Disorder or just rage, much of it arises from the same reality—the sense that we have been devalued or disrespected. The offended driver lashes out because another driver didn’t respect the fact he had the right of way. A community becomes enraged because it senses that the police and other authorities treat its people differently than others. Feeling belittled, we seek to re-assert our rightful place in the relationship by lashing out, playing the victim or exacting revenge. Rage gives us a way to re-assert our significance. But that is not necessary for those who follow Jesus. No one was more devalued and disrespected than he was. Here is God’s son, rejected, arrested, tortured and stripped naked on the cross—and not for anything he had done but for our sin and the sin of those who crucified him. And yet does he explode in anger? Does he lash out in revenge? No. Instead, he says, “Father, forgive them.” His significance is given by God. He is so secure in God’s love that he is able to seek grace even for those who despise him. And so are we. As those in whom his Spirit dwells, we are in Christ. As such, we know that nothing can separate us from his love or strip us of our identity—not even those who offend or hurt us. And because we find our significance in Christ, we seek for them--and give to them--grace. Nowhere is that clearer than in Stephen. We don’t know a lot about Stephen. Scripture tells us that when the apostles became too busy teaching the faith to handle the food distribution to the widows and orphans, they invited the people to identify seven Spirit-filled men to serve as deacons. Stephen was one of them, and he proved to be a man full of grace and power. In fact, God did so many wonders and signs through him that some in the synagogue had him arrested and hauled before the temple authorities. It was during his trial, that Stephen recounted the history of God’s people, the people of Israel. He spoke of how God had worked through Abraham and Isaac, of Jacob and Joseph, of Moses and David. But he also spoke of how time and again the people rejected God’s work. He reminded them of how the patriarchs had sold Joseph into slavery and how those 3 who had been slaves in Egypt murmured against Moses in the wilderness. And He ended the sermon by saying that they, just like their ancestors, were stiff-necked people, uncircumcised in heart and ears, because they had murdered Jesus, the Messiah. As you can imagine, the religious leaders seethed with anger. Picture a pack of rabid dogs growling and you have the image of what Stephen saw in their faces. And yet Stephen was not yet done. Looking upward, he saw the heavens open and Jesus standing at God’s right hand. “Look,” he said to them. “Look, I see Christ at the right hand of God.” Well, that was when the religious leaders exploded. They dragged Stephen out of the city and stoned him. So offended were they by the suggestion that they had killed the Son of God that they violated both the Roman Law and the laws of Moses to perform the equivalent of a lynching. And yet even as they were hurling their stones at him, Stephen refused to return their rage with more rage. Oh, he could have, like the Prophet Zechariah, called for vengeance. “May Yahweh see and avenge,” the prophet cried shortly before his death. But Stephen didn’t. Rather than ask God for their heads, he asked that they be forgiven. Rather than explode in rage, he followed the example of Jesus, and prayed, “Lord, do not hold this sin against them.” Rather than curse them for the wrong they had done to him, he sought for them grace and peace from God the Father through Christ the Son. He prayed that they too might find the antidote to their IED. Lest you think only saints like Stephen are capable of seeking such grace recall what happened in Charleston, South Carolina, a week and a half ago. A mentally ill man filled with racial hatred showed up at an African-American church’s prayer service and cold-bloodedly kills nine people who had gathered for nothing more than prayer. Taking their lives was the ultimate offense, the ultimate devaluing of them and those who loved them. And yet people who had every right to be enraged, every right to explode in anger, stood in front of TV cameras less than 24 hours later and offered forgiveness to the man who killed those they loved. How could they do that? They knew their identity was in Jesus Christ. They knew they were loved and forgiven. They knew their significance was given by God, and try as he might Dylan Roof could not diminish or destroy that. Or consider another simple saint. She was sitting on the porch of her shotgun home when her grandson walked up the street, his face dirty and his clothes tattered. Through tears, he told his grandmother that he’d been set upon by boys from his school and that he wanted to kill them. Wiping is his face with the sleeve of her blouse, she pulled him unto her lap, and told him she knew exactly how he felt. “A long time ago,” she said, “back when black people and white people didn’t much mix, the police called me to say my son had been killed. They told me they didn’t know who did it and probably never would, but I knew what they meant. White folk had killed him. 4 “I went down to the hospital, claimed his body, gathered the family and buried him. And the next morning, I got up, went to the house of the white family where I worked, woke up their two little children, fed them breakfast and sent them off to school.” “But Mammaw,” the boy asked, “why didn’t you just kill them? Why didn’t you get even?” “Because,” she said, “that’s not what Christians do. We do what I have done every day since. We pray that whoever killed my baby might come to know the grace of Jesus.” In a world where people often seem to look for reasons to explode in anger and violence, it is easy to get caught up in the rage. It’s easy to get offended, to take every perceived snub as an affront to our dignity and value. But those who know Jesus as Lord have their significance in him. And that love, identity and significance cannot be diminished by the thoughtless slight of strangers or even the deliberate insults of enemies. Instead, that identify makes it possible for us to seek God’s grace for those around us, even those whose words and deeds have left us, as they left Jesus, scarred.