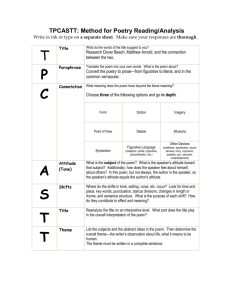

Figurative Language

advertisement

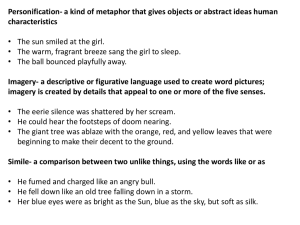

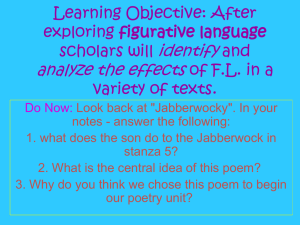

Figurative Language What does it mean when someone uses ‘figurative language’? It simply means that it is not to be taken literally. For example: Time is running out. (Is time really running? No, but we know what is meant by the saying. He talked her ear off. (Goodness! That would be a sight!) He bit off more than he could chew. He was in way over his head. She was under the weather. It was more fun than a barrel of monkeys! GRAMMAR is the necessary structure of language--the sounds, words, syntax, and semantics. RHETORIC is what we do with the language, the choices we make with words, phrase structure and placement, and the tricks we use to make the language more noticeable and memorable. STYLE is the noticeable pattern of choices of one person or a group of people who adhere to a similar pattern of choices. FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE involves the purposeful distortion of language, the use of non-literal constructions which delight the mind or make us think about what a writer is getting at. What makes figurative language work is that a reader knows the patterns of literal language and recognizes the distortion. If the reader does not identify the figurative language, mere confusion of meaning results. The difficulty of figurative language can be overcome when we discover that all figures of speech are actually based on comparison and contrast. When we discover that some language can’t be taken literally, we are forced to compare what we have with what it might have been. Thus, we get two sets of meaning. Each figure approaches the comparison differently. Recognizing Literal Language You have probably read or heard someone make a comment similar to this one: The store was literally bursting with shoppers! In this case, the person is not using the word literally in its true meaning. Literal means "exact" or "not exaggerated." By pretending that the statement is not exaggerated, the person stresses the fullness of the store. Literal language is language that means exactly what is said. Most of the time, we use literal language. Recognizing Figurative Language The opposite of literal language is figurative language. Figurative language is language that means more than what it says on the surface. It usually gives us a feeling about its subject. For example, one poet writes about the "song of the truck." She does not mean that a truck can actually sing. Rather, she is speaking figuratively. She is referring to road noises as music. By using the word song, and suggesting music, she brings joyful feelings to mind. Poets use figurative language almost as frequently as literal language. When you read poetry, you must be conscious of the difference Otherwise, a poem may make no sense at all. For example, can you explain these lines from "The Storyteller" He talked, and as he talked Wallpaper came alive. Of course, the poet is not using literal language. He doesn't mean that the wallpaper literally jumped off the walls. Rather, he is using figurative language. This exaggeration suggests the power of the storyteller. Sometimes the literal meaning of a line does not make sense, and only the figurative meaning does. At other times, both literal and figurative meanings make sense. As you read poetry, you must be alert for statements with both literal and figurative meanings. Recognizing Symbols Sometimes a writer uses something physical, like an object or color, to stand for an idea. The thing that stands for something else is called a symbol. You are familiar with some symbols in everyday life. For example, in street signs, the color red is a symbol of danger. In writing, a symbol is a type of figurative language. If a writer repeatedly refers to one object, you might suspect that it may be a symbol. Decide whether it might stand for something besides itself. An Approach to Reading and Writing About Poems 1. Read the poem aloud several times to determine the tone. (Is it bitter, cheerful, colloquial, formal . . . ?) 2. Identify the theme or central idea and the "message" of the poem. 3. Pay careful attention to the punctuation in order to determine the structural and/or rhetorical units into which the poem is divided. 4. Observe the relationship, if any, between the structural units and the rhyme scheme. Do not merely identify the rhyme scheme; if you are going to talk about rhyme, you must explain how it affects the tone of the poem, relates to the structure, or helps communicate its "message." 5. Identify images. Remember that images are always concrete; they create a mental picture, e.g. trees, sunset, fire burning out in Shakespeare's Sonnet 73. Consider how the images affect the tone, theme and "message" of the poem. 6. Identify figurative language used in the poem; know proper terminology for the types of rhetorical figures of speech used. Consider how the figurative language affects or contributes to the tone, theme and "message" of the poem. 7. Consider the effect of the diction (word choice), e.g. Shakespeare's Sonnet 30 uses terms from finance and law. How does the use of particular words or a pattern of diction affect tone and meaning or contribute to the "message" of the poem? Here you should also notice any unusual word choice and consider its function. 8. Naturally, look up all allusions and any word you do not understand. If your dictionary does not satisfy your needs, go to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), which gives the range of historical meanings of the word and cites examples of how it has been used in various contexts. 9. Verbal devices: notice e.g. patterns of word repetition within the poem. Consider the effect of such repetition, of the inversion of normal word order, etc. (see e.g. Sonnet 129). 10. Consider the use of conventions, e.g., the "blazon" in which the poet itemizes the charms of his mistress from head to waist. In Sonnet 130, Shakespeare treats this convention ironically in the first twelve lines; in the concluding couplet, he turns around and adopts the stance of the admiring lover. 11. Carefully analyze the way in which each unit of the poem and each device functions in relation to the whole. (How do they contribute to the poem's "message" or help to get its meaning across?) Remember: the best reading of a poem accounts for each part of the poem in relation to the whole. Explain the poem and show how if works AS A POEM (it is not just a prose paraphrase of the poem's content). Omit all phrases such as "it seems to me," "I feel" and "I think" -- after all, the whole analysis is YOUR interpretation. Your job is to explain the poem -- not your feelings about it. FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE IMAGE - representation in words of sense experience; words which appeal to one or more of the senses; a visual image may be called a mental picture. "the goat-footed balloonMan whistles" -e. e. cummings "Two roads diverged in a yellow wood" -Frost METAPHOR - an implied comparison of two unlike things; a direct verbal equation of two or more things that may at first seem unlike "Let us eat and drink for tomorrow we shall die" "Life the hound Equivocal" -Robert Francis "Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player That struts and frets his hour upon the stage And then is heard no more. . ." -Shakespeare SIMILE - comparison of two unlike things using "like" with nouns and "as" with clauses "Like to the falling of a star, . . . . Even such is man," -Henry King SYMBOL - a specific idea or object that may stand for ideas, values, persons or ways of life; something that means more than what it is "The Road Not Taken" "The Tyger" PERSONIFICATION - giving human characteristics to an animal, object, or concept (something nonhuman); a subtype of metaphor in which the figurative term is always a human being "Because I could not stop for Death-He kindly stopped for me--" APOSTROPHE - addressing someone absent or something nonhuman as if it were alive or present and could respond "Tyger, Tyger, burning bright" -Blake PARADOX - an apparent contradiction which is actually true "Where ignorance is bliss, 'tis folly to be wise." OVERSTATEMENT or HYPERBOLE - exaggeration used to achieve emphasis "All night I made my bed to swim; with my tears I dissolved my couch." -Psalms 6:6 "I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence." -Frost UNDERSTATEMENT - saying less than what is true; the deliberate undervaluing of a thing to create emphasis (may exist in what one says or in how one says it) "For destruction ice is also great and would suffice" -Frost VERBAL IRONY - saying the opposite of what is meant "My Papa's Waltz" -Roethke "Was he free? Was he happy" The question is absurd." -Auden, "The Unknown Citizen" IMAGE -means only what it is METAPHOR - means other than what it is SYMBOL - means what it is and something more, too