toolkit 10 - modification of contracts

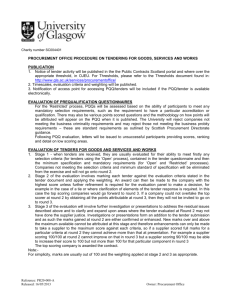

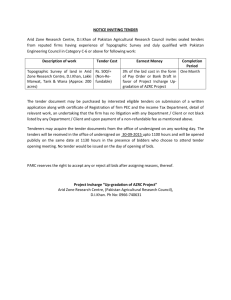

advertisement