TRAVAUX LINGUISTIQUES DE PRAGUE

advertisement

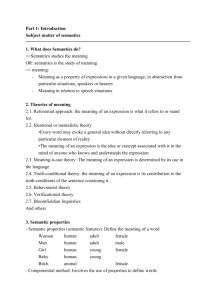

TRAVAUX LINGUISTIQUES DE PRAGUE 1 L'École de Prague d'aujourd'hui ACADEMIA ÉDITIONS DE L’ACADÉMIE TCHÉCOSLOVAQUE DES SCIENCES PRAGUE 1966 LIBRAIRIE C. KLINCKSIECK PARIS 1 Table des matières JOSEF VACHEK, Prague Phonological Studies Today Studies in Structural Grammar 7 FRANTIŠEK DANEŠ–JOSEF VACHEK, Prague Today BOHUMIL TRNKA, On 21 the Linguistic Sign and the Multilevel Organization of Language KAREL HORÁLEK, Les fonctions de la langue et de la parole ALOIS JEDLIČKA, Zur Prager Theorie der Schriftsprache BOHUSLAV HAVRÁNEK, On Comparative Structural Studies of Slavic Standard Languages KAREL HAUSENBLAS, On the Characterization and Classification of Discourses OLDŘICH LEŠKA, Zur Invariantenforschung in der Sprachwissenschaft PETR SGALL, Zur Frage der Ebenen im Sprachsystem VLADIMÍR HOŘEJšÍ, Chronologie relative et linguistique structurale VLADIMÍR SKALIČKA, Konsonantenkombinationen und linguistische Typologie ARNOŠT LAMPRECHT, Sur le développement et la perte de la correlation de mouillure en ancien tchèque PAVEL TROST, Funktion des Wortakzents JIŘÎ KRÁMSKÝ, A Quantitative Phonemic Analysis of Italian Mono-, Di- and Trisyllabic Words MIROSLAV KOMÁREK, Sur l'appréciation fonctionnelle des alternances morphonologiques FRANTIŠEK V. MAREŠ, The Proto-Slavic and Early Slavic Declension System IGOR NĚMEC, A Diachronistic Approach to the Word-Formative System of the Czech Verb ALEXANDER V. ISAČENKO, The Morphology of the Slovak Verb HELENA KŘÍŽKOVÁ, MILOŠ DOKULIL, Zum wechselseitigen Verhältnis zwischen Wortbildung und Syntax FRANTIŠEK DANEŠ, A Three-Level Approach to Syntax IVAN POLDAUF, The Third Syntactical Plan LUBOMÍR DOLEŽEL, Vers la stylistique structurale JAN FIRBAS, On Defining the Theme in Functional Sentence Analysis JIŘI NOSEK, Notes on Syntactic Condensation in Modern English MIROSLAV RENSKÝ, English Verbo-Nominal Phrases Liste des abréviations 33 41 47 59 67 85 95 107 111 115 125 129 145 163 173 183 203 215 225 241 257 267 281 289 300 2 Als Motto könnte man über diesen Aufsatz –oder über die auslösenden Überlegungen– ein Zitat von Roger Bacon schreiben: citius emergit veritas ex errore quam ex confusione. Der Aufsatz wurde nach einer Kopie gescannt und digitalisiert. Die Fußnoten wurden dabei unter den Text gestellt. Für die völlige Korrektheit des Wortlauts wird keine Garantie übernommen. František Daneš A THREE-LEVEL APPROACH TO SYNTAX I. It appears that much confusion in the discussions of syntactic problems could be avoided if elements and rules of three different levels were distinguished. The respective levels are: (1) level of the grammatical structure of sentence (2) level of the semantic structure of sentence (3) level of the organization of utterance To start with, let us consider the way in which CHOMSKY1 treats the notion of "grammatical relation". Thus, e.g., on p. 518 he states that in the sentence John is easy to please, "John is the direct object of please (the words are grammatically related as in 'This pleases John')", while in the sentence John is eager to please the word John ,,is the logical subject of please (as in 'John pleases someone')". – It is even the terminology ("direct object", "grammatically related", "logical subject") that reveals the confusion of notions. Chomsky is, of course, right that in John is easy to please the words (more precisely: their meanings) John and please are related as in "This pleases John", but one wonders why to call this relation a grammatical one (Chomsky himself, to be sure, uses, in the second case, the adjective "logical", others would use perhaps another attribute, viz. "psychological"), since it has nothing to do with the formal grammatical properties of the given sentence. On the same page Chomsky compares sentences (1) Did John expect to be pleased by the gift? and (2) The gift pleased John and comes to a conclusion that in the sentence (1) the expressions "John", "please" and "gift" are grammatically related as they are in (2). Should it mean that there is no grammatical difference between a construction with passive infinitive functioning as object and that with passive predicate? Or between prepositional adverbial determiner (by the gift) and subject (the gift)? But what difference is it, then, if it is not a grammatical one? Yet it is obvious that it is exactly the identity of semantic ("logical") relations (as the background) and the differences in grammatical structures that contribute to the syntactic specificity of such sentences. One must ask, why, in this case, Chomsky has abandoned the syntactic notions of subject, object etc. and –225– recurs, though tacitly, to the "logical" (i.e. semantic) level; it is clear that all "traditional" grammars would identify the word John in (1) as subject, while in (2) as object, etc. On the other hand it is true that many grammarians would define the grammatical categories of subject etc. by enumerating semantic elements that are usually expressed (rendered) by them. But this is rather a paradoxical proceeding, for then the question arises, why there should be so many different elements, as actor (in active constructions) and patiens (in passive constructions) etc., put together under a single term, and why just these elements, and not others. Thus it turns out that the subject (etc.) as a grammatical category can be established on the grammatical level only (e. g. subject being that element of the sentence that depends on no other element). Like many others, Chomsky, apparently, does not respect the difference between the grammatical and the semantic level in syntax.2 Such terms as "subject", "object" are taken over into the gene1 N. CHOMSKY, The Logical Basis of Linguistic Theory, in: Preprints of Papers for the Ninth Intern. Congress of Linguists, Cambridge, Mass., 1962. 2 To this point, a statement by CHOMSKY seems to be of some interest: "As the grammatical rules become more detailed, we may find that grammar is converging with what has been called logical grammar" (Some Methodological 3 rative grammar from "traditional" grammars without caution and without any serious attempt at critical revision, and applied in a very vague manner. We are far from denying the importance of the semantic considerations in syntax; on the contrary, we are convinced that the interrelations of both levels, semantic and grammatical, must necessarily be stated in order to give a full account of an overall linguistic system. However, to make such a statement possible, a strict differentiation of both levels is indispensable. That does not mean, of course, a "separation of levels", but only a methodological step which enables us, on the next step, to ascertain their systemic interaction. Let us now first give a sketchy account of the level of the semantic structure of sentence. 3 From our conception of the sentence (see here in Section II) it follows that it is only the linguistic relevant generalizations of concrete lexical meanings that enter the semantic structure of the sentence, not the concrete meanings themselves. Such generalizations possess the form of abstract word-categories (e.g. living being, individual, quality, action), or of relations between these categories (e. g. action as feature of an individual). – From an analytic point of view, the sentence structure is based on that kind of relations that is sometimes called "logical" (cf. above in Chomsky's paper); these relations are derived from nature and society and appear to be essential for the social activities of man. E.g.: actor and action; the bearer of a quality or of a state and the state; action and an object resulting from the action or touched by it, etc.; different circumstantial determinations (determ. of place, time...); causal and final relations, relations of consequence, etc. Semantic relations like these are linguistically rendered in different languages differently, with different depth and width –226– (and must not be confused with grammatical categories of subject, object, etc., as already mentioned above). As for the grammatical level, it can be characterized by the fact that it is autonomous, and not one-sidedly dependent on the semantic content; consequently, it is a rather self-contained and determining component. Thus, the grammatical categories such as subject etc. are not based on the semantic content, but on the syntactic form only; they are bearers of a linguistic function in the given system. The autonomy of the grammatical form reveals itself in the fact of diversity of languages (while the semantic categories, being extra-linguistic, seem to be universal, or nearly so). The autonomy and dominance of grammar does not mean that there is no correspondence between both levels; but it must be underlined that e.g. the relation between the grammatical sentence elements and the respective semantic categories is not that of identity, but of a close or distant affinity. As will be shown more explicitly in Section II of the present paper, the kernel syntactic relation is that of dependence (corresponding to the relations of determination and predication, that are the most abstract relations of the semantic level), which may be rendered by means of morphological devices (agreement, government, adjunction), word-order, etc. Another (but an asyntagmatic) relation is that of adjoining.4 The basis for the syntactic structure represents the hierarchy of the parts of speech (in a morpho-syntactic classification). The central concept of this level is the socalled sentence pattern. The third level is that of the organization of utterance. 5 To put it briefly, it "makes it possible to understand how the semantic and the grammatical structures function in the very act of communication, i.e. at the moment they are called upon to convey some extra-linguistic reality reflected by thought and are to appear in a adequate kind of perspective" (J. FIRBAS, o. c., p. 137). The Remarks on Generative Grammar, Word 17, 1961, p. 237, footnote 32). Cf. also some remarks by E. M. UHLENBECK in his critical article An Appraisal of Transformation Theory, Lingua 12, 1963, pp. 1—18. 3 The following discussion is based on ideas expounded by M. DOKULIL and FR. DANEŠ in their study K tzv. významové a mluvnické stavbě věty [On the So-Called Semantic and Grammatical Structures of the Sentence] in: 0 vědeckém poznání soudo-bých jazyků [On the Research into Contemporary Languages], Praha 1958, pp. 231 to 246. 4 Instead of "dependence" and "adjoining", more usual, but not fully synonymous terms "subordination" and "coordination" might be employed. 5 Cf. V. MATHESIUS, Zur Satzperspektive im modernen Englisch, Archiv für das Studium der modernen Sprachen u. Literaturen, 84, 1929, Bd. 155, pp. 200—210. J. FIRBAS, Notes on the Function of the Sentence in the Act of Communication, SPFFBU 1962, A 10, pp. 134—148, and other papers by the same author. 4 conditions of the act of communication are determined by the general character and regularities of the linear materialization and linear perception of utterance on the one hand, and on the other by the extra-linguistic content of the message, by the context and situation and by the attitude of the speaker towards the message and towards the addressee. Thus into the domain of the organization of utterance pertains all that is connected with the processual aspect of utterance (in contrast to the abstract and static character of the other two levels), that is to say, the dynamism of the relations between the meanings of individual lexical items in the process of progressive accumulation, as well as the dynamism of all other elements of utterance (semantic and grammatical too), arising out of the semantic and formal tension and of expectation in the linear progression of the making-up of every utterance. –227– Further, all extra-grammatical means of organizing utterance as the minimal communicative unit are contained on this level as well. Such means are: rhythm, intonation (as a complex of "melody" and "stress"), the order of words and of clauses, some lexical devices, etc. (Still, some of them may be operative on the grammatical level, too.) The framework for the dynamism of the utterance represents "the functional perspective" in a strict sense, i.e. the principle according to which elements of an utterance "follow each other according to the amount (degree) of communicative dynamism they convey, starting with the lowest and gradually passing on to the highest" (Firbas, o. c., p. 136). In this way, an utterance may usually be divided into two portions: the theme (or topic), conveying the known (given) elements, and the rheme (or comment), conveying the unknown (not given) elements of an utterance.6 The same principle is operating even in organizing the context.7 The functional perspective employs different devices in different languages; e.g., in Slavic languages it is mainly the word order and intonation. Thus it appears that the organization of utterance disposes of special means of systemic character, which have been, wrongly, classed with grammar (syntax) or stylistics. A "theory of utterance" should be postulated (cf. here in Section II), in which all non-grammatical means and processes of organizing utterance and even context should be treated (together with the grammatical ones). The necessity of an independent interpretation of all the phenomena pertaining to this level could be demonstrated very clearly e.g. in treating the complicated problems of word-order.8 On the other hand such an interpretation enables us to discover and describe the interactions of all three levels pertaining to syntax (in a broader sense). The present author tried to do so in the sphere of intonation of utterance.9 And it should be required, that in treating of any syntactic problem or phenomenon, an analysis on all three levels should be accomplished and the structural interpretation sought for in the relations and interactions of all levels.10 I shall adduce at least one concrete example: In Czech, the agreement (in gender and number) of predicate with a compound subject containing nouns of different genders and/or numbers may have, according to circumstances, three different forms: (1) the predicate agrees with the first noun, (2) it agrees with the last noun, (3) it agrees with the 6 This principle has found its way recently even into the generative grammar; cf. E. BACH, o. c. (note 23), p. 268. — Cf. also P. NOVÁK, 0 prostředcích aktuálního členění [On the Means of Functional Sentence Perspective], AUC 1959, Philologica I, pp. 9—15. 7 The significance of the principle of the functional perspective for the information and communication theory and for the automatic information retrieval is quite evident. 8 Cf. e. g. J. FIRBAS, Notes on... (see note 4), FR. DANEŠ, K pořádku slov... (see note 24), E. BENEŠ, Začátek německé věty z hlediska aktuálního členění výpovědi [The Sentence Initial in German from the Viewpoint of the Functional Perspective of Utterance], CMF 41, pp. 205 - 218. 9 Cf. FR. DANEŠ, Intonace... (see note 24). SAME, Sentence Intonation from a Functional Point of View, Word 16, 1960, pp. 34—54 10 Cf. FR. DANEŠ, Vedlejši věty účinkově přirovnávací se spojkou než aby [Consecutively Coloured Comparative Subclauses with the Conjunctions ..než aby"], NR 37, 1954, pp. 12 ff. — SAME, Konfrontačni souvětí se spojkami jestliže, zatímco, aby, když [Subclauses Denoting Confrontation with the Conjunctions jestliže, zatímco, aby, když], NR 46, 1963, pp. 113ff. 5 subject as a whole (its form depending, then, on certain grammatical rules). Now, if we try to find the rules of distribution for (1), (2), (3), it appears that the rules are conditioned by the position in the utterance of the predicate in respect to the subject: rule (1) may be employed, if the predicate precedes the subject; (2) may be employed (but rarely) if the predicate follows the subject; (3) may be employed with the predicate in any position in the utterance, but more often if the predicate follows (according to this rule the predicate "summarizes" the compound subject as a whole). Thus the explanation of this distribution must be sought for not on the grammatical level, but in the organization of the utterance, in its progressive making-up. –228– II. The kernel concept in syntax is the concept of the sentence. This term appears in all syntactic research work; nevertheless its content seems to be very variable and vague. It covers elements of very different nature and a complex, undifferentiated concept like this leads to much confusion in discussions and to many uncalled-for mistakes. In order to cope with this unsatisfactory situation, we suggest that in the content of the term "sentence" three different basic concepts should be distinguished: (1) Sentence as a singular and individual speech-event. (2) Sentence as one of all possible different minimal communicative units (utterances) of the given language. (3) Sentence as an abstract structure or configuration, i.e. as a pattern of distinctive features; the set of such patterns represents a subsystem or the overall grammatical system of the given language.11 For clarity's sake let us call the concept (1) the utterance-event, the concept (2) the utterance, and finally the concept (3) the sentence pattern.12 As will be shown further, a great majority of utterances represent manifestations of a small set of sentence patterns; such utterances may be called shortly sentences. (Those utterances that are based on no underlying sentence pattern might be called non-grammatical ones.) It is clear that the above three stages represent three steps in the process of generalization. What belongs to speech (la parole) and represents material immediately accessible to our observation, are the utterance-events.13 If we deprive such an event (by way of abstraction) of all accidental, singular and individual elements, connected with its phonic (or graphic) "ego hic et nunc" manifestation, we arrive at an utterance14 which no longer belongs to speech, which, however, contains many more 11 It was duly claimed by C. C. FRIES (in: Trends in European and American Linguistics 1930—1960, UtrechtAnvers 1962, p. 221), that "the sum of the speech acts of a community... does not constitute its language. The language (la langue) is the rigid system of patterns of contrastive features...” — In contrast to it, linguists oriented toward mathematics and logic define language as an unlimited set of sentences or expressions. —As for the generative grammars, it is not quite clear whether the "terminal strings" are abstract patterns or particular utterances (sentences). 12 The distinction between the sentence as an individual utterance and the sentence pattern as a unit of the grammatical system is based on the ideas of the late V. MATHESIUS, most fully expressed in his study On some Problems of the Systematic Analysis of Grammar, TCLP 6, 1936, pp. 95—107. 13 The notion of a singular utterance-event is more complex than one would expect. In fact, beside the really singular utterances (spoken or written), there exist, in the graphic plan, multiplicated utterances ("copies", mainly printed), and in the phonic plan utterances with the possibility of repeated reproduction ("conserves": magnetic tape, gramophone record, sound track and other types of sound transcription). Then we have to distinguish events of two different ranks: as "events of the first rank" may be labelled single copies (of a certain edition of a book) or reproductions (e. g. of a gramophone record); differences between these "events" are rare and indistinct, of course; as "events of the second rank" may be labelled collections of copies belonging to the same edition (issue). In some cases it is possible to distinguish even three ranks; e. g. (1) single reproductions of the identical gramophone record, (2) single gramophone records containing the identical sound transcription (and belonging to the identical issue), (3) collection of gramophone records of the identical issue (containing the identical sound transcription). 14 Under the term "utterance" there is meant here, in essence, what has been called by S. KARCEVSKIJ la phrase (cf. TCLP 4, p. 190, Sur la phonologie de la phrase): "La phrase est une unité de communication actualisée. Elle n'a pas de structure grammaticale propre... N'importe quel mot ou assemblage de mots, n'importe quelle forme grammaticale, n'importe quelle interjection peuvent, si la situation l'exige, servir d'unité de communication". (Quite a different meaning is given to the term "the phrase" in the generative and transformational grammar; I. I. REVZIN (in his book Modeli jazyka [Linguistic models], p. 60) refers to Karcevskij wrongly.) — Our "sentence" corresponds to Karcevskij's 6 features than only those belonging to the most abstract and general syntactic pattern of the grammatical system: the utterance remains a part of context and of situation, it contains concrete lexical items, some elements of modality (which are often expressed by non-grammatical means, e.g. by means of lexical items or of intonation), etc. Thus on the second step of generalization we arrive at the utterance. By analysing it we discover: (1) Non-grammatical, but systemic means of its organization, such as mostly word-order in Slavic languages (as far as it serves as a means of organizing the utterance and context), intonation as a device of integration, delimitation and segmentation of utterances, or –229– emphasis and modality, etc.; I would suggest to call the phenomena of this sort "suprasyntactics" (this term has been coined by DEAN S. WORTH in his paper presented to the Ninth International Congress of Linguists), and to postulate a special branch of linguistics dealing with non-grammatical elements and rules of organization of utterance (together with the grammatical ones); it might be called "the theory of utterance".15 (2) On this step of generalization we ascertain even some grammatical elements, which, however, do not belong to the constitutive features of a sentence pattern (e.g., mostly the use of morphological categories, such as moods, tenses, or even the grammatical agreement in an utterance that is not based on an underlying sentence pattern). And, finally, only on the third, highest step of generalization is obtained the specific grammatical device16 of the organization of utterance, viz. the sentence pattern. We will now discuss the conception of the sentence pattern in some detail. Under the term sentence pattern we understand then, generally speaking, a syntactic structure of the kind that it converts a sequence of words into a minimal communicative unit (an utterance) even outside the framework of connected discourse, i.e. even then when it has been taken out of its settings (the situation and the context). It is such a structure as is sufficient by itself to signal a given sequence of words as utterance. Thus from the viewpoint of its function, the sentence-pattern is a specifically communicative structure, an utterance-making device. Non-grammatical utterances, being based on no underlying sentence patterns, derive their communicative validity (function) from the situation, context and intonation (in spoken language) or from graphic devices (in written and printed language) only. Let us now consider the procedure of discovering sentence patterns. From their function it follows that the corpus of such an inquiry must be the set of utterances corresponding to the given condition, viz. that they employ the communicative function even outside the context and situation. More essential (and complex) seems to be the question which of the grammatical elements contained in a given utterance should be included into the sentence pattern; strictly speaking, which it is necessary to include, and which, on the contrary, one should exclude from it, so that the requirement of a complete and at the same time minimal unit could be met. Criteria for such procedure follow from the fact that the sentence pattern is the unit of a system: the set of all sentence patterns of a given language represents a partial system built up of oppositions, and each pattern may be considered a structure of those syntactic features that differentiate a given pattern from the other items of the given system. Our task is to render all constitutive (i.e. distinctive and invariant) features and to ascertain all –230– items of the system and their respective positions in it (i.e. their hierarchy). A la proposition (cf. o. c., p. 189). 15 Such phenomena have been usually (and inconsequently) treated in grammar and in stylistics. The specificity of this problem was pointed out by V. SKALIČKA, The Need for a Linguistics of 'la parole', in: RLB 1948, pp. 21ff., and E. PAULINY, La phrase et l’énonciation, ibidem, pp. 59 ff.; cf. also FR. DANEŠ, K vymezení syntaxe [Some Notes on the Delimitation of Syntax] in: Jazykovedné štúdie 5, Bratislava 1959, pp. 41 ff..; K. HAUSENBLAS, Sýntaktická závislost, způsoby a prostředky jejího vyjadřování [Syntactic dependence, the ways and means of its manifestation] in: Bulletin VSRJL 2, 1958, pp. 23—51; V. SKALIČKA, Syntax promluvy (enunciace) [The Syntax of Utterance (Enunciation)], SaS 21, 1960, pp. 241—249. 16 In accordance with KARCEVSKIJ (o. c.), we restrict the concept of grammatical syntax to the domain of the syntagmatic and asyntagmatic relations only; thus intonation remains mostly outside the grammar. Cf. KARCEVSKIJ: "(La phrase) n'a pas de structure grammaticale propre. Mais elle possède une structure phonique particulière qui est son intonation. C'est précisément l'intonation qui fait la phrase". 7 kind of homomorphism between the phonemic and syntactic plans may be traced here. Constitutive grammatical features of sentence patterns are: the parts of speech (in morpho-syntactic classification), some morphological categories and two relations of syntactic connexity, viz. dependence (a syntagmatic, and non transitive, irreflexive and asymmetric relation) and adjoining (an asyntagmatic, and transitive, reflexive and symmetric relation); the word-order belongs into the sentence pattern only in those cases where it has a grammatical function (in Slavic languages very rarely); consequently, in the following patterns the order of symbols is irrelevant (the relevancy of it should be marked). The sentence pattern in this sense represents an abstract and static invariant structure (scheme), not a sequence of particular words in a particular utterance, based on this underlying pattern. It is not possible to derive here the patterns step by step; we must limit ourselves to clearing up the basic principles on some representative examples only. (The symbols are explained in the Appendix, p. 236-7.) It turns out that the description of sentence structures may be suitably presented in the form of a hierarchically ordered system of patterns supplemented by a set of rules. If the pattern represents the invariants of the given class of utterances, then the rules ascertain the variable (and yet systemic) syntactic components, i.e. facultative syntactic variants of the given pattern. Thus for instance the sentence17 Starý učitel píše u stolu dopis synovi (U stolu píše dopis starý učitel synovi) (U stolu píše dopis synovi starý učitel) is based on the pattern18 (1) (PROp1) VF (S4) "At the table an old teacher is writing a letter to his son" The parentheses denote potential elements (positions) of the pattern, i.e. those structural elements whose manifestation in the corresponding utterances is not obligatory, but whose potential existence constitutes a distinctive feature (in opposition to other patterns). Thus in the example (1) the element S4 (dopis synovi) is not a necessary one (cf., e.g., the utterance Starý učitel píše19, which is grammatically correct, and, at the same time, not an elliptic one), but the constant possibility of inserting it distinguishes the pattern (1) from the pattern (2) (PROp1) VF –231– which does not contain this potential element (cf. e.g. Starý učitel jde velmi pomalu "The old 17 The present discussion is based on materials of Standard Czech. As for the other possible interpretation, see here p. 234. "This utterance, based on the pattern (1) (PROp1 ) VF ( S4) must not be confused with utterances of the type Náš chlapec už píše "Our boy writes already", having the meaning "he can write"; here the underlying pattern is (2) (PROp1 ) VF, so that the verb form píše "he-writes" in (1) and (2), respectively, manifests, in effect, two syntactically homonymous verbs. Thus an utterance of the type On už píše is syntactically ambiguous, being the manifestation of two different sentence patterns. To put it in other terms: the opposition between the two patterns, viz. (1) and (2), does not, under certain conditions, become affected. That is to say, an incidental syntactic ambiguity of an utterance does not impair the structural differences between the underlying patterns; the level of language system and the level of its manifestations must be strictly kept apart. This is, of course, also the case of Chomsky's type Flying planes can be dangerous, etc. (Cf. here on p. 234.) 19 An ambiguity like this must be distinguished from an ambiguity of another type. E.g., in a Czech utterance like V těchto dolech cínovec provází wolfram "In these mine tin is accompanied by wolfram" or "wolfram is accompanied by tin" the syntactic homonymity does not lie in the incidental co-occurrence of two underlying patterns, but in a casual homonymy of morphological forms of the nominative case (subject) and accusative case (object); in both possible interpretations the same (identical) pattern is employed. 18 8 teacher is walking very slowly"), on the one hand, and on the other from the pattern (3) (PROp1) VFS4 in which, in contradistinction, the element S4 is not potential, but constantly present, obligatorily manifested (cf., e. g., Starý učitel potkal mladého studenta "The old teacher met a young student", but never *Starý učitel potkal "The old teacher met", except as an elliptic utterance in an explicit context). In Czech the forms like Piše u stolu "[He-]writes at the table", Potkal mladého studenta "[He-] met a young student", Chodí pomalu "[He-] walks slowly" (i.e. forms without an explicit subject) are fully grammatical and quite common; nevertheless they always allow an insertion of the potential element PROp1, so that they stand in opposition to utterances of the type Uhodilo, ("The lightning has struck", impers.) in which such an insertion of the element PROp1 is not allowed and, which, consequently, are based on the following pattern:20 (4) VF3 sg n Let us return to the pattern (1): by filling in particular word-forms we obtain, e. g., the utterance (On) píše dopis; at the variant Starý učitel píše u stolu dopis synovi we arrive by employing the following rules: (a) PROp31 = S; (b) S == S A (učitel == starý učitel "[a] teacher" = "[an] old teacher"), S == S S3 (Dopis synovi "[a] letter to [his] son"), VF == VF prS (píše u stolu "[he-] is-writing at [the] table"). Rules of the type (b) may be called expanding rules; the use of the sign == shows that they are based on the principle of structural syntactic equivalence of the expressions on both sides of it. The number of such rules is, of course, large; e. g. VF = VF ADV, S = S INF, A = A A ADV; ADV = ADV ADV; rules may combine (S =S ; VF = VF ADV ADV,...), A and some of them are capable of a more general form (e.g. instead of VF == VF prS we may write VF == VF Si i.e. the noun may stand in any indirect case and be governed by a preposition). From the very essence of rules it follows that they do not pertain to one pattern only, but that they are valid in general or at least in a certain group of patterns. Consequently, for every pattern such expanding (and other) rules must be indicated as are valid in its case; and, vice versa, for every rule –232– all patterns to which it pertains (or, more simply, to which it does not pertain) should be indicated. It is clear that in this way the rules are engaged in the hierarchical ordering of the system of sentence patterns. The rules of the type (a) may be called substitution rules; e. g. PROp31 = S1 by which the pronoun of the third person in nominative case (of both numbers) may be substituted by a noun (cf. e. g. (On) píše – Otec píše),21 It may be shown that the possibility (or, respectively, impossibility) of applying this rule to a certain pattern is one of the distinctive features: thus in the pattern (3) (PROp1 ) VF S4 the element (PROp1) may be substituted by the element (S1), viz. in a subclass of 20 The restriction expressed by the subscript 3 sg n represents another distinctive feature, viz. the impossibility to use the verb in a form different from the indicated (i.e. a paradigmatic restriction). Of course, even here we meet with the already mentioned structural syntactic ambiguity (homonymy): an utterance in which the verb stands, exactly in the form VF3 sg n may represent the manifestation of both patterns: (1) (PROp1 ) VF S4 (4) VF3 sg n 21 One might suggest also a rule by which the syntagm PRO1 VF or S1 VF would be reduced to VF only (a "reduction" rule). But this would be of little use; nevertheless, it shows the central position of VF in Czech sentences and the particular position of a syntagm PRO1/S1 VF ("predicative syntagm") in the pattern: it is the dominating (governing) and not the dependent member of the syntagm that disappears if the reduction rule is employed (in contradistinction to the others syntagms). Cf. also J. KURYLOWICZ, Les structures fondamentales de la langue: groupe et proposition. Studio philosophica 3, 1939–46, pp. 203 ff. 9 utterances containing this element in the form PROp31 while in another pattern, viz. (5) (PROp1 ) VF3p1ma S4, (underlying, e. g., the utterance Starého učitele vyznamenali "The old teacher has been distinguished", in fact "[They-] have distinguished the o. t.")22 in which, according to the rule of grammatical agreement, the element PROp1 may acquire the value of PROp3p1ma1 only, the substitution of (S1) may not be applied. Thus the impossibility of applying the substitution rule is, beside the paradigmatic restriction23 expressed by the subscript 3 pl m a, another distinctive feature distinguishing the patterns (3) and (5). Besides expanding rules and substitution rules, there exist other types of rules as well. In the first place extending rules, of the form S = S 1 + ...+ Sn (e. g. otec, matka a děti "father, mother and children"), based on the relation of adjoining. All types of rules may be combined; e.g.: S=S INF A1 + A2 (pevná a nezlomná vůle zvítězit "[a] firm and inflexible will [to] win"). Quite a different type of rules is represented by the rules of agreement; they are means of expressing the colligation of elements in a syntagm or in a group (of adjoined elements); in a syntagm, the dependent member may be held for a dependent variable (it acquires values according to the governing member). They should be stated in general for all patterns and rules and are applied quite automatically in the process of the formation of the utterance. Let us now return once more to the pattern (1). It is clear that all three utterances (listed on page 231) differ as to their word order, but are based on an identical pattern. The differences between them seem to be irrelevant on the grammatical level (on the level of sentence patterns). All three utterances (and other possible variants of that kind) might then be called "allo-sentences". The differences in word-order of that kind ("suprasyntactic") are governed by rules belonging into the domain of the theory of utterance (the word-order is employed as means of the functional perspecti–233– ve and of the organization of context). – But the word-order in the sentence (a) U stolu píše starý učitel dopis synovi is even capable of another, fundamentally different change, viz. (b) U stolu píše starý učitel synovi dopis. In the form (a) and in its two variants, based on the pattern (PROp1 ) VF ( S4), the element S4 has been expanded according to the rule S = S S3, or more generally, S = S Si (dopis synovi "[a] letter to [his] son"), while in the case (b) this rule has not been applied and, in contradistinction, the element VF has been not double, but threefold expanded: VF = VF prS S4 S3 (píše u stolu dopis synovi “[he-]is-writing at [the] table [a] letter to- [his] son “) Thus in these two cases the position of the element Si in respect to S4 has a distinctive function and must be treated in grammar; owing to its general character, however, it belongs to the sphere of rules and should appear in the form of the corresponding rule, e.g. expressed by means of a double arrow: S = S Si (it means, S must be immediately followed by Si). But a closer inspection of our utterances reveals that even the type (a) is not necessarily always unambiguous. The "fixed" word-order "noun (S) followed immediately by a noun in the form Si" does, in fact, only allow the interpretation S ==> Si (i. e., Si depending on S), but, in general, both 22 In Czech grammatical tradition such sentences are called "sentences with a general subject" ("man-Sätze"). Cf. the notion of "syntactic paradigm" in D. S. WORTH'S contribution to the Fifth Intern. Congress of Slavists "The Role of Transformations in the Definition of Syntagmas in Russian and other Slavic Languages", Mouton & Co, The Hagues. 23 10 interpretations, viz. S ==> Si and VF —> Si, are possible. Thus the fixed word-order constitutes a necessary condition for the interpretation S ==> Si, but not a sufficient one. It is the semantic content, context and situation that prefers (or excludes), in the particular case, one of two possible interpretations.24 Let us, in this connection, once more return to the problem of syntactic ambiguity (or homonymy). As on other linguistic levels, ambiguity exists only in the domain of manifestations (materializations) of systemic linguistic units; since it is exactly the existence of two (or more) distinct abstract systemic units, underlying a single phonic (or graphic) sign that justifies the notion of ambiguity or homonymy, and of neutralization of oppositions as well. It is not the abstract grammatical sentence patterns that may be ambiguous (homonymous), but their manifestations only, i. e. concrete utterances. If we consider language (and grammar, as a constituent of it) as an abstract system of relations and an instrument by means of which all members of a given community are enabled to construct utterances and to understand them (in this sense grammar, with respect to the speaker and to the hearer, has to be viewed from a "neutral" viewpoint)25, then it is clear that it makes no sense to speak of ambiguity in grammar. Ambiguous or homonymous may be merely utterances, and from the viewpoint of the hearer (decoder) only, the speaker knowing always exactly what sentence pattern he has employed.26 –234– Word-order as a factually distinctive feature of patterns may be found in a pair of sentences of the types: (6) Má bolavou nohu "He has a sore foot" and (7) Nohu má bolvou "His foot is sore" (the adj. bolavou "sore" stands in attribute in (6) and in predicate in (7); the corresponding patterns are: (6) (PROp1 ) VF S4 (7) (PROp1 ) VF S4 => A Beside the fact that in (7) a double dependence occurs, the difference between both structures lies in the position of the adjective: in (6) it precedes the S, in (7) it must not precede it. This distinctive feature should be marked in the pattern (7); as for the pattern (6), a special expanding rule S 4 = A => S4 should be employed.27 It may be added that in some types of syntagms the order of elements is fixed, nevertheless it does not enter into contrast with another order; such an order might be called a "fixed" or "restricted" one and its rules belong to the same type as the rules of agreement, viz. they are employed in the process of formation of the utterance. – A special case of it is found, e.g., in English sentences of the type John hates Mary versus Mary hates John: in the underlying pattern the order of elements S => VF => S is fixed (restricted), but it is not contrasting on this level, since "the differing orders result simply from the lexical options chosen, where two positions in a construction may be filled by members of the same class"28 (so that the contrast is found on the level of utterance only). From the fact that in the cases just mentioned the order of elements does not operate as a distinctive (contrasting) feature in the system of sentence patterns it does not follow that it is irrelevant. The fixed order is an integral part of the pattern (or of the rule) and belongs to its invariants. The functional relevance of the English word-order S => VF => S is revealed, e. g., by a comparison with Czech: As already mentioned (Note 19), Czech utterances of the type Cínovec provází wolfram are ambiguous, while the corresponding English counterpart Tin accompanies 24 The only possible English equivalent of both Czech sentences, viz. At the table an old teacher is writing a letter to his son, is, owing to the restricted word-order, always ambiguous. Cf. Chomsky’s example The police suspected the man behind the bar. 25 In this point we are in agreement with CHOMSKY'S theory (but not practice); cf. his article On Certain Formal Properties of Grammars, Information and Control 2, 1959, pp. 137 ff. 26 The problem of syntactic ambiguity is thoroughly discussed (in the framework of a model describing the way which leads from a sentence pattern to the corresponding set of utterances) by F. DANEŠ, Opyt teoretičeskoj interpretacii sintaksičeskoj mnogoznačnosti, VJa 1964 (in print). 27 A detailed discussion of the principles of word-order see in FR. DANEŠ, K otázce pořádku slov v slovanských jazycích [On the Problems of Word-order in Slavic Languages], SaS 1959, pp. 1 ff. 28 E. BACH, The Order of Elements in a Transformational Grammar of German, Language 38, 1962, pp. 263—269. 11 wolfram is quite unambiguous, due to its fixed word-order. This fact leads to conclusions of a more general character: Among the constitutive features a of systemic linguistic unit there are found not only distinctive features established as members of an opposition, but also features which enter no opposition, and may, consequently, be considered as concomitant or redundant, which, nevertheless, appear to be indispensable and integral components of the unit, being operative and relevant on a different level (in our case on the level of utterance). Features like this might be perhaps called "constants" (in contradistinction to distinctive features)29 and their ascertainment should be an indispensable component of linguistic description of units of any level. –235– Concluding our tentative and rather sketchy exposition of the concept of sentence pattern 30, we would like to emphasize that the system of sentence patterns and corresponding rules accounts for one partial aspect of the field of syntax only, viz. that which might perhaps be called syntactic paradigmatics. Among others, we have left aside, for the present, the domain of transformational relations, which – beside the paradigmatic and syntagmatic ones – play an important part in the grammatical system of language. Undoubtedly even the elaboration of a system of sentence patterns cannot dispense with transformations. Besides, it seems to us that the concept of the semantic pattern (on the level of syntactic semantics) might prove to be helpful. We mean patterns like: process; agent – action – the object of action; the bearer of state – state; individual – predication of a feature to it; individual – placing it into a class; etc. It would be of some interest to ascertain their relations to all different corresponding grammatical sentence patterns by which the former ones are linguistically rendered (expressed). It might even be suggested that the notion of syntactic transformations presupposes semantic patterns of this or that kind as invariants. (This seems to be confirmed by Chomsky's interpretation of the notion of "grammatical relation"; cf. here on p. 225 ff.)31 29 The author of the present paper has called attention to this important fact in his book Intonace a věta ve spisovné češtině [The Sentence Intonation in Standard Czech], Praha 1957, p. 46. Cf. also R. JAKOBSON'S trichotomy of elements; "marked – unmarked – redundant", in his contribution of the Fifth Congress of Slavists "Opyt struktural’nogo podchoda k slavjanskoj istoričeskoj akcentologii". 30 The first version of that concept can be found in the contribution of the present author to the Fifth Intern. Congress of Slavists. Cf. his paper Syntaktický model a syntaktický vzorec [Syntactic Model and Syntactic Pattern] in Českostovenské přednášky pro V. mezinárodní sjezd slavistů (Czechoslovak Contributions to the Fifth Congress of Slavists), Praha 1963, pp. 115—124. 31 Cf. also A. V. ISAČENKO. Gramatičnost a význam [Grammaticality and Meaning], AUC, Slavica Pragensia 4, Praha 1962, pp. 47—51. — R. B. LEES, The Grammar of English Nominalizations, Indiana University 1960 (esp. Preface and p. 2 f.). 12 Appendix Explanation of symbols employed in Section II Base-type letters: S noun (substantive) VF finite verb (in indicative or conditional mood and active voice) A adjective ADV adverb PRO pronoun INF infinitive pr preposition Subscripts: sg singular pl plural m masculine f feminine n neuter a animate gender –236– 1,2,3,.. nominative, genitive, dative, ... (with S); or: first, second, third person (with VF) i any indirect case (also with preposition) Superscripts: p 1,2,3, (in combination PROp) personal pronoun (of the first, ... person) 1,2,3, differentiate adjoined elements in the same group Signs: denotes the relation of dependence (the arrow points to the dependent member) => denotes the fixed order of elements + denotes adjoining of elements of the same degree of dependence () parentheses denote a potential element (position) in the pattern == denotes the syntactic equivalence of two elements (or groups of elements) 13