The Fletchers: First Family of Sweet Briar Plantation

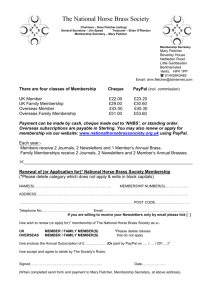

advertisement

The Fletchers: First Family of Sweet Briar Plantation by Julissa Yabar Elijah Fletcher lived at a time when the nation was torn between those who advocated and those who opposed the enslaving of African Americans. At a time when the North and the South were drawing clear lines of delineation on the issue of slavery, Elijah Fletcher was drawing equally clear and often similar lines between himself and his family, between himself and other Southern slaveowners, between himself and the African Americans with whom he shared the Southern landscape. Drawing extensively on the diaries and correspondence of Fletcher and his family, this essay discusses Elijah Fletcher as a slaveowner, with particular reference to his Northern background and his place in the Southern hierarchy. This essay also discuss the lives of those African Americans whom Fletcher held in bondage at Sweet Briar Plantation and the complex and fragile relationships which existed between black and white Southerners. Elijah’s brother, Calvin Fletcher, was strongly abolitionist, in direct opposition to Elijah’s chosen way of life. Calvin wrote to his wife of the Southern states’ promotion of slavery that “They are wrong & a succession of wrongs must produce its awful consequences. I tremble for the future.” (CF to his wife 1841, Thornbrough 291) Elijah himself, soon after his arrival in Virginia in 1810, referred to slavery as “a curse to any country.” (EF to his father 1811, Von Briesen 45) While Elijah left Vermont and sought his fortune in Virginia, Calvin moved to Indiana based on its status as a “free state.” Calvin and Elijah remained fraternally close, Calvin even visiting his brother in Virginia. Calvin’s antislavery views did not agree with all of his Southern relatives. Of Elijah’s younger son, Lucian, it was said, “[Lucian] does not exactly like his uncle Calvin, for [Calvin] told [Lucian] he ought to black his own shoes, and [Lucian] says he is no negro to do such work.” (EF to his brother CF 1830, Von Briesen 111) The tensions within the Fletcher family underscore the tensions felt within Elijah himself. He wrote to his brother of the South, “This is a bad country in which to bring up boys. I wish mine could be raised in the indigence and simplicity that you and I were. You may feel very happy that you are not in a slave state with your fine Boys, for it is a wretched country to destroy the morals of youth.” (EF to his brother 1831, Von Briesen 122) Even with these misgivings, Elijah remained in the South, reaping the benefits and profits of the slave system. He wrote of the “comfortable and agreeable situation” made possible by having “black servants enough.” (EF to his father 1813, Von Briesen 76) Elijah does not appear to have anticipated or encouraged his own change in values, but rather to have stumbled into a time and place where owning slaves provided the status and power he desired. For much of his life, however, he expressed misgivings about the institution of slavery while enjoying its benefits. Slavery is rather a misfortune than a crime. The present holders of slaves are not censurable for their father’s crimes of introducing them. They’re only censurable for not treating those they possess well. We have some free negroes here, and it is a general remark that the slaves who have good masters are in a better situation. To emancipate them at once would be the height of folly and danger. You must not think too badly of slaveholders—for your son is one. But be assured he is not fond of that species of property and whatever portion of it fortune or necessity places under his care, he will use every endeavor to make their situation as agreeable and comfortable as possible. They never shall want for victuals and cloathes and how I despised the man who would trafic in human flesh. My feelings may be a little softened by living in a country where such things are common, but they never will be perfectly reconciled to them. (EF to his father 1813, Von Briesen 77-78) Elijah’s opinions on the matter of slavery were clearly tempered by the slaveholding environment in which he lived. Soon after his arrival in Virginia, he caught wind of rumors regarding Thomas Jefferson’s indiscretions with one of his slaves, Sally Hemmings. “The story of black Sal is no farce. That he cohabits with her and has a number of children by her is a sacred truth, and the worse of it is, he keeps the same children slaves, a unnatural crime which is very common in these parts.” (EF to his father 1811, Von Briesen 36) The South in which Fletcher lived was one struggling to defend and preserve the institution of slavery. Men like South Carolina’s James Henry Hammond, whose views on slavery are like Fletcher’s preserved in diaries and correspondence, possessed extreme views on the merits and causes of slavery. Hammond, in a speech on the floor of the Congress in 1836, said that “slavery is said to be an evil, it is one to us alone, and we are content with it - why should others interfere… it is no evil.” (Bleser 11) In light of such extremes, it is little surprise that Elijah Fletcher fell quickly into line with the supporters of slavery, those who benefited most from the practice. Throughout his years in the South, Elijah was curious about and observant of the African Americans around him. In one of his first letters written to his family after arriving in Virginia, Elijah described the enslaved African Americans he saw about him daily. “…I saw a herd of negroes in fields – men, women and children. Some dressed in rags, and others without any cloathes.” (EF to his brother 1810, von Briesen 12) Fletcher was perhaps more sympathetic to those he held in bondage than some of his contemporaries, treating those enslaved on his property with what he believed was “Christian” courtesy. He thought that many African Americans possessed intellectual and spiritual skills and viewed them as a far better workforce than their free white peers. “I have more dependence in my Servants than in most any White man I procure. They become intelligent in their work and never tire at their work. No country supplied better workmen. The Contractors in our public works dismiss all foreigners and employ hired slave labor except in some nice Mechanical work.” (EF to his brother 1849, Von Briesen 219) As throughout the South, enslaved African Americans had a variety of duties on Fletcher’s plantation, ranging from working in the fields to serving in the Fletcher household. When possible, Fletcher added to his income by hiring out his slaves to individuals and companies in Central Virginia. Shortly before his death, Elijah was asked by [N. Gill of ] if Mr. Gill could “hire next year a large force of Black hands to work in Aston Quarry.” (N. Gill to EF 1857, SBC Archives) Due to the demand for hired slaves, many of the enslaved African Americans owned by Fletcher experienced a high degree of mobility. This served to separate family members, even if for only short periods. Fletcher appears to have been sensitive to African-American wishes to avoid separation, perhaps more sensitive than many of his contemporaries. In 1854, Miles Nelleys wrote Fletcher on behalf of Fletcher slave Betsey. “Sir though the request of Betsey there wish to inform you that Mr. Mikfields who hired her and her daughter will move from Lynchburg about the first of next month and consequently intends hiring out Betsey for the remainder of the year and intends taking with them Betseys daughter. Betsey seems to be unwilling for Mr. Mikfields to carry her daughter over the mountains and therefore would be glad if you would prevent her being removed.” (Miles Nellys to EF 1854, SBC Archives) There is reason to believe that Elijah Fletcher treated his slaves as well as or better than many of his contemporaries, but there is equal reason to believe that, like most white Southerners, Fletcher knew the value of his enslaved property. He informed his father in 1825 that he “had a Negro Boy about ten or 12 years old die last week. He had been sick some time. Such a Boy is worth in case from $350 to $400. This kind of property is now rising.” (EF to his father 1825, Von Briesen 97) If for no other reason than their economic value, Fletcher sought to treat his slaves with some degree of humanity, in 1855 going so far as to prepare “a happy Christmas for [his] Servants.” He desired that “None [of the slaves] fear that they will suffer or have any little want which will not be gratified.” (EF to his brother 1855, Von Briesen 257) Despite such paternal displays, Elijah Fletcher certainly punished his slaves when he thought it necessary. In 1854, a neighbor complained that “2 of [Fletcher’s] negro girls Nancy and Juley came to my house yesterday pretending on business to see some of my family and on their return home they stool 3 of my largest water [melons]… I want you to correct them for it sir.” (Obudiah Gregory to EF 1854, SBC Archives) Much of what is now known about the lives of the enslaved African American community of Sweet Briar Plantation comes from recent archaeological investigations. This work augments the information available from the letters and diaries remaining from the plantation. Archaeological survey and excavation in the areas immediately surrounding Sweet Briar House have revealed evidence of domestic and service structures as well as artifacts, the remains of the activities which took place in and around these buildings. Ceramics were the most common artifact recovered, including pieces of creamware (dated as early as 1762), pearlware(dated as early as 1775), and whiteware (dated as early as 1820). Datable glass bottles were also recovered, as were nails, fragments of brick, pieces of window glass, buttons, and animal remains, all dateable to the mid-19th century. The objects recovered archaeologically may have been used as part of slaves’ plantation duties or may have been used within the homes of the enslaved African Americans, away from the notice of the Fletcher family. As archaeological investigations of the plantation continue, a more complex image of the lives of the enslaved community will emerge, an image not entirely recoverable from the documents written by the literate slaveowning class. Following the Civil War, African Americans continued to be a large and visible presence at Sweet Briar Plantation. While race relations throughout the South did not noticeably improve upon emancipation, there is evidence that the Fletcher family and some of the African Americans living in close proximity shared an affection for each other. Martha Taylor, enslaved by the Fletcher family before the Civil War, continued in service to the Fletchers after emancipation. Unlike many African Americans at the time, Martha was literate and corresponded with the Fletcher family. Elijah’s granddaughter Daisy wrote to Martha in 1882 that “We think a great deal of you all.” The lives of black and whites were very much intertwined in the 19th-century South. The prosperity of wealthy Southerners like Elijah Fletcher was built on the backs of enslaved African Americans. Soon after he arrived in the South, Elijah Fletcher described to his brother and reflected upon the institution of slavery. The rich planters have from fifty to an hundred negroes. They buy, and sell them, as we do our cattle. They are very valuable property. A negro man is worth five hundred dollars, a woman not so much. They drive many from this state to South Carolina and Georgia. Some men make it their principal business to buy droves of them, and drive off, as our drivers do cattle. The greater part of them have some kind of cloathing except the children who go mostly naked. They have but very little to eat and are under the constant eye of an overseerer, who makes them work from sunrise, till sunset. They give them all their weeks allowance on Sunday, which must last them the week out. They whip them for every little offence most cruelly. I recollect last week, General Mason sent one of them two or three miles with some message. He was rather lazy, and thought he would have a ride. He went into the pasture, and caught my mare, and took a little negro boy on behind him, and rode off. It was found out soon, and when he returned they first tied up the boy and whipt him about a quarter of an hour, and he was begging and praying, yelling to a terrible rate. They then took the man, and I assure you, they shew him no mercy. They more he cried and begged pardon, the more they whipt and in fact I thought they would have killed the poor creature. I told them I did not care any thing for the ride of the mare. They said it would not do to indulge them. They must whip them till they were humble and obedient. General Mason has about sixty of them. He has a very large plantation. (EF to his brother 1810, Von Briesen 14) The materials left behind by Elijah Fletcher create a picture of a man reconciling the conflict between the cultures of his childhood and his manhood, between his race and the race he enslaved, between himself and his contemporary class equals. Elijah’s brother Calvin discussed in his diary the importance of “a good code of morality,” of the “most tender and delicate feelings.” Elijah shared a similar belief in morality and value, creating from his moral background a personal ethic that worked within the unethical system of Southern slavery. These complicated cultural and personal reconciliations may be seen within the hundreds of pages written by the Fletcher family. Works Cited Bleser, Carol. Secret and Sacred: The Diaries of James Henry Hammond, a Southern Slaveholder. Oxford University Press: New York, New York 1988. Von Briesen, Martha. The Letters of Elijah Fletcher. University of Virginia: Charlottesville, Virginia 1965. Faust, Drew Gilpin. James Henry Hammond and the Old South: A Design for Mastery. Louisiana State University Press: Baton Rouge 1982. Thornbrough, Gayle. The Diary of Calvin Fletcher. Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis: volumes I, II, IV 1972.