View/Open - Lirias

advertisement

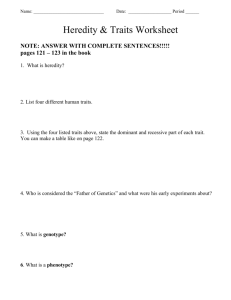

GOOD AND BAD FOR SELF AND OTHER EVALUATIVE MEANING PROCESSES IN SOCIAL COGNITION Guido Peeters K.U.Leuven Paper presented at: Agency and Communion in Social Cognition Symposium at the 14th General Meeting of the E.A.E.S.P. 19th-23th July 2005, Wuerzburg, Germany For a revised and extended draft of this paper, see: Peeters, G. (2007). Good and bad for self and other: From structural to functional approaches of fundamental dimensions of social judgment. Extended draft of presentations held at the Small Group Meeting 'Fundamental Dimensions of Social Judgment: A View from Different Perspectives', Namur, June 7-9, 2007, and at 'Trente Années de Psychologie Sociale avec Jean-Léon Beauvois: Bilan et Perspectives', Paris, June 27-29, 2007. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Briefly after I had submitted a proposal for a presentation at the present EAESP meeting, I received Bogdan Wojciszke's invitation to participate in his symposium. Apparently Bogdan's and my ideas fit well together, for I could readily stick to my initial proposal and have it inserted in his program. I have only slightly shifted emphasis from implications regarding stereotyping to implications regarding the presentations of colleagues at the symposium. Hence, although stereotyping is still an issue in the following presentation, it has been removed from the title. The central topic of this symposium concerns the nature and implications of a duality of valued concepts (categories, dimensions) underlying social cognitive information processing. They are referred to as agency and communion. However, as indicated by Bogdan in the introduction of the symposium, they have been implemented by different theorists working in different contexts emphasizing different aspects, developing different explanations, and using different labels. In the following I will discuss one of those implementations, being the duality of self-profitability (agency) and other-profitability (communion), henceforth abbreviated as SP and OP. 1. Origin, Operationalization and Cross-cultural Application of SP and OP In the late sixties I was facing the practical problem that the good-bad connotation of trait adjectives could vary across contexts. Hence, in order to obtain evaluative impressions of targets that would allow for valid comparisons between targets, I needed rating scale markers with goodbad connotations that would remain constant across contexts. Having inventoried a set of trait adjectives to which judges had assigned constant good-bad values across contexts, it struck me that those traits seemed to be primarily good versus bad for others dealing with possessors of the traits rather than for possessors of the traits themselves. For instance, tolerant and intolerant may be expected to involve good, respectively bad, consequences for others in the first place. Consequences for the tolerant or intolerant people themselves may only follow indirectly in that the others may reward the tolerance and punish the intolerance they have experienced. In the 1 heydays of Thibaut and Kelley it was fashionable to pick up terms from economics to designate analogous psychological contents. I still remember to have hesitated between (positive vs. negative) "utility" or "profitability", but do not remember why "profitability" was selected. So "good-bad for others" became + (positive) vs. - (negative) OP. Traits with variable good-bad connotations across contexts (powerful, competent vs. their opposites) seemed primarily good versus bad for the possessors of the traits themselves, and, for that reason, their good-bad values were called + (positive) vs. - (negative) SP. 1.1. Operationalization of SP and OP Quite some way has been gone with operationalizations of SP and OP (see Peeters, 1992). The most straightforward operationalization may simply require judges to rate the degrees to which traits involve good versus bad consequences for the possessors of the traits and for the others dealing with the possessors (De Boeck, & Claeys, 1988; De Bruin, 1999). One main problem with this direct method is that secondary +SP is confounded with primary OP, and secondary OP with primary SP. For instance, generosity (primary +OP) is assumed to have positive consequences for the self in that others reward generosity (secondary +SP); competence (primary +SP is assumed to have positive consequences for others in that judges readily assume solidarity rather than hostility between persons, in which case high competence may be beneficial to one's fellows (secondary +OP). In order to catch primary SP and OP as well as possible, I have ultimately arrived at the following indirect method. The indirect method. Two steps are involved. As a first step, the direct method is used to select sets of pure positive and negative SP and OP traits. These are traits that are judged extremely positive or negative on one dimension and neutral on the other. For instance, "ambitious" has been selected as pure +SP in that being ambitious is rated, on the average, as quite favorable for the self but neither favorable nor unfavorable for others. In this way four sets of four or five pure traits--also called key traits-- are selected. In Schema 1, American, Flemish and Italian sets of key traits are presented. As to the Flemish key traits, there are "standard sets" from Peeters (1992), which have been used in most of the studies, and parallel sets drawn from De Boeck & Claeys (1988), which have so far been used in only one study (see below). As a second step, SP and OP values of other traits are measured by asking judges to rate how well the traits belong to the different (standard) sets of key traits. For instance, in order to determine the SP value of "courageous", American judges were presented with the sets of -SP and +SP American key traits, which were told to be two "trait families". Then the judges were asked to indicate on a rating scale whether "courageous" belonged rather to the one or rather to the other trait family. In this way normative trait lists or "dictionaries" have been constructed with SP and OP values of American (Peeters, 2001a), Flemish-Dutch (Peeters, 1997) and Italian (Peeters, Amatulli, & Serino, 1998) trait adjectives. Recently, Bos (2005) has used the same indirect method to determine SP and OP values associated with nouns (persons). Although the method seemed workable for nouns, it seemed less so than for adjectives. The reason is probably that when judges are asked to estimate how well a noun fits a particular set of key traits, they may check how well the traits describe the noun. Thereby they may not only attend to SP and OP values, but also to irrelevant idiosyncratic meaning contents carried by the traits and the noun. Those idiosyncratic meanings may be ignored when the judges do not consider how well a particular noun is described by the key traits, 2 but how well a particular trait would fit in with the family of key-traits "as another member of the trait family". Hence a better method for determining SP and OP values of noun stimuli, also used by Bos, may require judges to describe the noun using a limited number of traits they may select from the traits listed in the dictionary. SP and OP values of the noun are obtained by computing the average SP and OP values of the selected traits. Nevertheless, the agreement between both methods was high, Bos reporting correlations amounting to .96 for OP and to .87 and .52 for SP, whereby the lower correlations for SP may be due to smaller variances. 1.2. Comparison with an Alternative Operationalization Meanwhile a different operationalization of SP and OP was developed by Wentura, Rothermund, & Bak (2000). They first selected a set of positive and a set of negative trait adjectives and then divided both sets into SP, OP and a non-classifiable rest category by asking judges to classify the selected adjectives into (a) traits having direct consequences for the person (possessor of the trait) him/herself, (b) traits having direct consequences for persons of the environment, and (c) not classifiable. Wentura and colleagues applied this procedure to German adjectives, 27 of which matched Dutch adjectives from the Flemish-Dutch dictionary (Peeters, 1997). The agreement for SP and OP values was very high. In the "dictionary" SP and OP values assigned to traits ranged between 100 (most negative) to 900 (most positive) with 500 as a neutral middle. SP and OP values of the Dutch matches (methodisch, theoretisch, terughoudend) of three non-classifiable German traits (systematisch, theoretisch, zurückhaltend) averaged respectively 557 and 512, which is near to the neutral middle. For seven +OP traits from the German list (rücksichtsvoll, freundlich, treu, gastfreundlich, tolerant, einfühlsam, ehrlich) average SP and OP values of Dutch matches (fijngevoelig, vriendelijk, trouw, gastvrij, tolerant, gevoelig, eerlijk) amounted respectively to 553 (quite neutral SP) and 774 (quite positive OP), while for 10 -OP traits (grausam, heimtückisch, jähzornig, betrügerisch, gemein, geizig, streitsüchtig, rabiat, aggressive, intolerant) the averages of Dutch matches (wreed, vals, opvliegend, bedrieglijk, gemeen, gierig, twistziek, brutaal, agressief, onverdraagzaam) amounted to 460 (quite neutral SP) and 231 (quite negative OP). For six German +SP traits (scharfsinnig, ausdauernd, intelligent, vergnügt, klug, glücklich) averages of Dutch matches (scherpzinnig, volhardend, intelligent, vrolijk, sluw, gelukkig) amounted to 652 (SP) and 609 (OP),while for two -SP traits (ohnemächtig, unfähig) averages of Dutch matches (zwak, onhandig) amounted to 202 (quite negative SP) and 445 (quite neutral OP). In spite of unavoidable errors due to the impracticability of perfect translation, the agreement between the two operationalizations of SP and OP is high. Some reservations regarding somewhat less convincing outcomes for SP may be abandoned if it is taken into account that the German list includend "selbstsicher" (+SP) and "träge" (-SP), of which the Dutch matches (zelfzeker, traag) were among the SP key traits relative to which SP values in the dictionary were determined. Those key traits were not included in the dictionary and so they were not involved in the above comparisons. Altogether, the convergent outcomes argue for the validity of both operationalizations. In the following, SP and OP values have been drawn from the "dictionaries" based on the indirect method described in section 1.1. 3 1.3. Comparing SP and OP Values of Stereotypes across Language-Culture Communities Some years ago I determined SP and OP values of 108 national stereotypes (Peeters, 1993). Most of the stereotypes were drawn from American publications and consisted of frequencies of traits attributed by Americans to various nationalities at different points in time. The traits were translated in Dutch and submitted to Dutch speaking Flemish judges who were asked to provide SP and OP ratings following the above indirect method. Actually it is on the basis of these ratings that the Flemish-Dutch "dictionary" of SP and OP values of traits (section 1.1) was constructed. Using the "dictionary", the SP (or OP) value of a stereotype was obtained by computing the weighted average of the SP (or OP) values of the traits involved, each trait being weighted by its relative frequency. The results showed some surprising outcomes. One surprising outcome was that SP values of stereotypes regarding the same nation were very stable over time, while OP values could show strong fluctuations. For instance, OP values of German and Japanese stereotypes formulated by Americans dropped dramatically when the U.S.A. entered the second world war and raised again immediately after the war was over, but SP values continued to be positive all the time. Apparently, stereotypes expressing negative communion reflect, possibly temporary, states of conflict. This was confirmed by Phalet and Poppe (1997) who found significant negative correlations between "morality" (communion) values of 54 national stereotypes and (territorial and economic) conflict between the stereotyped and respondent nations. Competence (agency) values of the stereotypes were found to correlate significantly with perceived (political and economic) power but not with conflict. The relative instability of -OP over time may be explained in that an adaptive function of the negative communal value of stereotypes would be the justification of competitive action (Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002). So the negative valence of OP holds just as long as the action may require. Anyway, there are good arguments to expect perceived agency to be more stable than perceived communion. This was recently confirmed by an analysis of SP (agency) and OP (communion) values of descriptions of the Prophet Mohamed drawn from Christian schoolbooks covering a time-span of nearly a century (Bos, 2005). Bos observed significantly more variability of OP than of SP. Comparison with an apparently much more positive description from an Islamic source yielded no difference for SP, the greater positivity being entirely a matter OP. The same author also found greater constancy of SP than of OP assigned to the same character from a comic strip across different scenes. Finally, the greater stability of SP than of OP seems also reflected by behavioral orientations relative to stereotyped SP and OP target groups according to the "BIAS Map" (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, this symposium). Taking into account that "warm" corresponds to +OP and "cold" to -OP, admired and pitied groups, which share +OP, elicit active facilitation (helping), and hated and envied groups, which share -OP, elicit active harm (attack). Taking into account that "competent" corresponds to +SP and "incompetent" to -SP, admired and envied groups, which share +SP, elicit passive facilitation (association), and pitied and hated groups, which share -SP, elicit passive harm (exclusion). This means that OP elicits active, rather episodic, actions such as helping and attacking that do not last, but can be repeated, which results in a fluctuating action pattern. SP elicits more passive, rather permanent states such as association and exclusion that may be constant for a long time. Another surprising outcome at the time concerned the contrast between positive national stereotypes (of own and friendly nations) and negative national stereotypes. As expected, the negative stereotypes were predominantly marked with -OP. However, the positive stereotypes 4 seemed marked with +SP rather than with +OP. This outcome may no longer surprise in the light of past and present research of other participants in this symposium, particularly research connecting agency with positive self-evaluation (Wojciszke, 2005) and social utility (Dubois, 2003)--see also Abele-Brehm (this symposium). However, at the time it was a surprise to me, and I had a suspicion that it might be an artifact due to imperfect translations of stereotype contents from English to Dutch. In order to check my suspicion I used the American, Italian, and Flemish-Dutch "dictionaries", described in section 1.1, and determined SP and OP values of the original "American" version of stereotypes and of Italian and Flemish-Dutch translations of the stereotypes. In this way American, Italian and Flemish-Dutch SP and OP values were obtained for 16 stereotypes held by Americans about eight nationalities at two points in time and reported by Child & Doob (1943). Each stereotype consisted of a fixed list of 20 traits (actually 21, but one trait "intellectual" was accidentally dropped from the analysis) with percentages of American participants that assigned the traits to the stereotyped nation. Using the percentages as weights, American, Italian, and Flemish-Dutch SP and OP values of the 16 stereotypes were computed as described above. For the sake of presentation, the SP and OP values were transformed to a scale with a potential range from -100 (most negative) over 0 (middle) to 100 (most positive). The results are presented in Table 1. Most of the outcomes are positive. The American SP values are systematically higher than the Flemish and Italian SP values, and the American OP values are higher than the Flemish but lower than the Italian OP values. This indicates that determining SP and OP values of stereotypes on the basis of translations of the stereotypes into another language may involve a systematic error, which argues against using the obtained outcomes as absolute measures of SP and OP. However, relative SP and OP values of stereotypes in comparison with each other showed high agreement between the original and translated stereotypes. As shown in Table 1, correlations range from .94 to .98, and even correlations between the two translated versions (Flemish and Italian) are still very high (.85 and .94). Apparently relative positions of stereotype descriptions within the SP and OP dimensions are preserved when the descriptions are translated into another language and SP and OP values of the translations are determined using norms established within the other language-culture community. Apart from the practical relevance of this outcome, it raises the question why translation errors would not detract more from the constancy of relative SP and OP values. An obvious explanation may be that translation errors are like random errors that cancel out each other. The validity of this explanation has been tested using SP and OP values of 120 traits from the American "dictionary" (Peeters, 2001a) and of the Italian translations of the traits (Peeters, Amatulli, & Serino, 1999). Correlations between values of original American and of translated Italian versions of the traits, computed across n = 120 traits, amounted to .71 for SP and to .82 for OP. These correlations are quite high and indicate that original SP and OP values are well preserved when traits are translated. However, they are expected still to increase when correlations are not computed across n = 120 traits, but across n = 60 average values of groups of k = 2 traits. Table 2 shows that, contrary to the expectation, the correlations do not increase. Even, when the number of combined traits is gradually increased up to k = 12, the correlations tend to fluctuate and even to decrease rather than to show a steady increase. An obvious explanation may be that when traits are randomly aggregated, not only errors but also positive and negative values outweigh each other making that the mean OP or SP values of the aggregates regress to the overall mean. This would result in reduced correlations because of decreased variability. In agreement with this rationale, variability of SP and OP values of aggregates involved in Table 2 is really inversely related to the size (k) of the aggregates. The ranges of SP 5 and OP values of aggregates decrease to about 50% (if k = 5) up to 26% (if k = 12) of the range for single traits (k = 1). It is worth mentioning that this observation holds for random aggregates but not for natural aggregates that are stereotypes. For stereotypes correlations increase indicating that random translation errors cancel each other. 2. Theoretical Foundation of the Universal Status of SP and OP (and of Agency and Communion by Extension) It became soon apparent that SP and OP could be matched with existing concepts regarding specific evaluative dimensions underlying social cognition corresponding to the present agency and communion. Meanwhile, good arguments have been advanced suggesting the universal character of those dimensions (e.g., White, 1980; Ybarra, this symposium). The present interpretation of the dimensions as "good-bad for self" and "good-bad for other" may contribute to add some theoretical foundation to the empirical universality. Indeed, SP and OP have been related to linguistic and cognitive universals such as the distinction between entities and relations as basic cognitive units, and the possibility to conceive of entities in three ways corresponding to pronouns of the first (I), second (you) and third person (he, she it) (Peeters, 1983). Specifically, the concepts of "self" and "other" that underlie SP and OP have been matched with the first and second person. This means that the +SP value of a trait such as "competent" implies that the possessor of the trait may view the trait as "good to me", and the +OP value of a trait such as "generous" implies that the possessor of the trait could view the trait as "good to you". The distinction between "you" and "me" being universal, it may not surprise to find a universal substratum underlying the categories "good to you" and "good to me". Obviously universality may not only be hypothesized for SP and OP but also for theories such as the Agent/Recipient Theory (ART) (Wojciszke, this symposium) that are based on the concepts self and other, at least if self and other are conceived as I and you. 2.1. Processing Information in the Self-Other versus Third-Person Way Apparently, the universal character of agency and communion, conceived as SP and OP, may be given a sound theoretical basis by stating that they are processed conceiving of perceived stimulus persons in the first and second person. However, what does "processing in the first and second person" mean, and how is it distinguished from "processing in the third person"? . At a first glance, one may argue that it is just a matter of use of words such as the pronouns me, you, he or she. However, words belong to the surface structure of language, while cognitive processing operates on the underlying deep-structural "meaning" level. Since Chomsky (1965), linguists have searched, largely in vain, to bridge the gap between deep and surface structures, e.g., by the construction of "transformational grammars" that would enable to transform the one into the other following formal rules. The point is not only that there are no simple one-to-one relationships between surface and deep structural units, but that surface-structural units such as pronouns may not be appropriate to describe the deep-structural units. Pronouns belonging to the surface structure, I have arrived at defining the deep-structural distinction between first, second and third person in terms of the ways in which a perceiver can deal with reflexivity and non-reflexivity of relational information (e.g., Peeters, 2004). Processing relations in the first and second person means that information value is accorded to the reflexive versus non-reflexive status of a particular relation. For instance, consider the 6 relation "helping out of trouble". Given the information that John helps X out of trouble, a perceiver who processes in the first and second person would wonder in the first place whether X is John himself or an other person. If X turns out to be an other person, the perceiver may expect John to be a generous and helpful person scoring high on communality. If X turns out to be John himself, John may be perceived as independent and self-confident scoring high on agency. It is possible, however, that the perceiver is only interested in John's competence to solve particular problems. For instance, if the troubles in question are troubles with solving mathematical problems, the perceiver may conclude that John is a competent mathematician. In that case, it does not matter whether X is John himself or another person, which means that the distinction between reflexivity and non-reflexivity of the relation "helping out of trouble" is ignored. The present deep-structural definition of first, second, and third person as ways of dealing with reflexivity has led to procedures enabling to measure the extent to which subjects process information either in the self-other way (taking reflexivity into account) or in the third-person way (ignoring reflexivity). In this way it has been found that the self-other way leads to personalized representations involving dispositional trait attributions, and the third-person way to depersonalized representations as in natural sciences. When processing information perceivers often stick to one way without being aware of the other way. Particularly information regarding interpersonal relationships tends to be processed unilaterally in the self-other way. However, expertness in a particular domain (e.g., music) has been found to stimulate the third-person way of processing interpersonal relations when the relations are presented in the context of the experts' domain of expertise (relationships between musical performers). This could be explained in that the so-called "third person" functions as a sort of cognitive dummy that can be filled with whatever personal or impersonal content one wants (Benveniste, 1966). In this way it is not only particularly suited to handle specialized expert knowledge, but, being free of the universal constraints associated with reflexivity and non-reflexivity, it is also suited to construct culturespecific conceptual frameworks such as Western natural sciences (Peeters, 2004). 2.2. Application to the Dual Status of Competence The duality of self-other and third-person ways of processing is relevant for understanding the dual status of competence put forward by Ybarra (this symposium). On the one hand there is the "universal understanding of the taskability domain" (Ybarra). It may be conceived as an undifferentiated concept of competence reflecting "self-profitability" and as such being processed in the self-other way. Indeed, competence is unconditionally associated with "good for self" but not unconditionally with "good for others". Hence terms denoting high competence may communicate "good for self", indeed, but not invariably "good for others", as is illustrated by the subtle lexical distinctions between the meanings of wise, intelligent, shrewd, astute, sly, crafty, and cunning. On the other hand there are specific competencies processed in the third-person way such as the mathematical competence in the above example. They correspond to Ybarra's culturespecific exemplars of the taskability domain. In this way, the distinction between self-other and third-person ways of processing offers a theoretical foundation of Ybarra's duality of primary universal and secondary culture-specific concepts of competence. Moreover it enables to connect that duality with a variety of other dualities in social cognition that are underlain by the duality of self-other anchored and third-person anchored processes (for a recent review, see Peeters, 2004). 7 3. Connecting SP and OP with Related Concepts 3.1. Behavioral Concomitants of Evaluation: Approach-Avoidance There is a long-standing tradition to connect general "good-bad" evaluation with approachavoidance tendencies of the evaluating subject relative to the evaluated object. This means that evaluation is conceived of in accordance with a spatiotemporal model, which is, moreover, a dynamic "locomotory" model (for an alternative static model of evaluation stressing presenceabsence rather than approach-avoidance, see Peeters, 1995). A similar model certainly makes sense from an evolutionary perspective (Martin & Levey, 1987) but it also involves particular constraints. One basic constraint is that, as long as space is not handled metaphorically, an actor can only approach or move away from an "other" object, but not from him/herself. It follows that the connection of evaluation with approach-avoidance can be expected to be limited to OP, not involving SP. This hypothesis has been confirmed by Wentura et al. (2000) for simple motor approach-avoidance responses and by Peeters, Cornelissen, & Pandelaere (2003) for socialbehavioral approach and avoidance. However, Peeters (2001b; Peeters et al., 2003) found also approach-avoidance behaviors associated with SP in certain conditions suggesting that the selective association of approach-avoidance tendencies with OP may belong to the actor perspective taken by the perceiver. A perceiver taking the perspective of an observer would associate approach-avoidance tendencies with SP as well. Meanwhile, further research has confirmed this hypothesis (Peeters, 2003). An interesting question may be how the latter outcomes regarding approach-avoidance concomitants of evaluation are related to the behavioral concomitants reported by Cuddy, Fiske & Glick (this symposium). In order to answer that question we should compare Cuddy et al.'s behaviors (see section 1.3) with the behaviors I used to operationalize social approach-avoidance. Actually my operationalization was based on a factor analysis of likelihood ratings of 12 social behaviors of a hypothetical target person relative to several "others" representing a variety of combinations of SP and OP (Peeters, 2001b). The behaviors were drawn from the literature on aggression, prosocial behavior and social distance. One factor accounted for 66% of the variance and was interpreted as a bipolar approach-avoidance dimension. Assumed approach behaviors (loading between .90 and .77) were: wanting the other as a friend, wanting the other as acquaintance, allowing the other to use his/her (the perceiver's) belongings, helping the other, wanting the other as a life-partner, wanting to collaborate with the other, indirectly helping the other by attending people to his/her need of help. Assumed avoidance behaviors (loading between -.84 and -.65), were: avoiding the other, thwarting the other preventing him or her from achieving his or her goals, ridiculizing the other, scolding the other, beating the other. It may be evident that the "approach" behaviors reflect both the active (helping) and passive (associating) variants of Cudy et al.'s facilitation behavior, and that the "avoidance" behaviors reflect both the active (attacking) and passive (excluding) variants of Cudy et al.'s harming behavior. Considering that +OP and +SP are both associated with "facilitation behavior", and -OP as well as -SP with "harming behavior", Cudy et al.'s data seem consistent with the outcomes from conditions in my studies where participants acted as observers estimating behavioral dispositions of a target person relative to an other on the basis of how the target viewed that other, rather than to estimate their own behavioral dispositions relative to the other on the basis of their own impressions formed of that other. 8 3.2. Evaluation according to Osgood's Semantic Differential The connection of SP and OP with the semantic differential has been discussed elsewhere (Peeters, 1986). A main point is that the procedure applied by Osgood and his colleagues necessarily leads to an apparently general evaluative dimension and one or more non-evaluative dimensions. The evaluative dimension of the semantic differential is represented by a mixture of (a) "directly evaluative" adjectives (good, positive, etc.) that communicate only agreement or disagreement with an evaluative standard of "approachability" without specifying the nature of the standard, and (b) descriptive adjectives that are "indirectly evaluative" by interaction with the context. The latter adjectives communicate descriptive features (sweet, agreeable, etc.) that happen to be positive (approachable) across a wide variety of current contexts. Their evaluative meaning can be defined as OP, being understood that, in agreement with section 2.1, the selfother anchored way of processing information, to which OP belongs, generates a personalized "animistic" discourse in which impersonal objects are (metaphorically) dealt with as if they would be persons (honest wine, friendly house, generous sunshine...). The so-called nonevaluative dimensions (potency, activity, combined into dynamism) concern features that are evaluative as well, but with valences that vary across current contexts. In this respect they correspond to SP. 3.3. Evaluation according to Peabody's Tetradic Model According to Peabody (1985), trait meanings are organized in accordance with descriptive dimensions, particularly the dimensions "tight-loose" and "assertive-unassertive". Trait adjectives that communicate extreme dimensional values carry negative valences connected with the ideas "too tight, too loose, too assertive, too unassertive". More moderate "optimal" values carry positive valences. In this way, each descriptive dimension is represented by a series of "tetrads" being sets of four traits such as in the rows with traits in Table 3(a), which represent the dimension "tight-loose", and in Table 3(b), which represent the dimension "assertiveunassertive". Examination of the traits suggested the hypothesis that trait valences advanced by Peabody were systematically related to OP and SP values in the ways indicated in Tables 3(a,b). Specifically, The positive valences associated with "optimally loose" and "optimally unassertive" would reflect +OP, and those associated with "optimally tight" and "optimally assertive" would reflect +SP. As to negative valences, the valences associated with "too tight" and "too assertive" would reflect -OP, and those associated with "too loose" and "too unassertive" would reflect -SP. In order to test these hypotheses, the 36 traits presented in Tables 3(a and b) were translated in Dutch and presented to four Flemish judges (PhD students). As the judges were quite fluent in English, each trait was accompanied with the original English term between parentheses. The judges rated each trait on SP and OP on scales ranging from -3 to +3 following the indirect method described above and using the standard sets of Flemish-Dutch key traits presented in Schema 1. The SP rating scale contrasted the -SP set (-3) with the +SP set (+3) and the OP scale contrasted the -OP set (-3) with the +OP set (+3). Although only four judges were involved, the ratings were reliable, Cronbach alpha amounting to .86 for SP and .85 for OP. An additional reliability check was provided by having the procedure repeated with another group of four judges (PhD students) and using the alternative parallel sets of key traits presented in Schema 1. 9 This time Cronbach alpha amounted to .93 for both SP and OP, and the correlations (over N = 36 traits) between the new and former values (averaged across the judges) amounted to .94 for SP and .90 for OP. Apparently the average SP and OP ratings were reliable indicators of SP and OP values of the traits. The obtained values are presented in Tables 3(a,b). As shown in the tables, SP and OP values were contrasted in a way consistent with the hypotheses. The confirmation of the hypotheses has several interesting implications. First, Peabody's concept of "evaluation" cannot be equated with "evaluation" as it has been operationalized by the semantic differential. Indeed, as explained above, the "evaluation" of the semantic differential is a matter of OP, but not of SP, while Peabody's "evaluation" is a conglomerate of both OP and SP. Second, the tetrads were designed in order to separate descriptive aspects of judgments (impressions, stereotypes) from evaluative aspects. If a perceiver describes a target as aggressive rather than peaceful, and, at the same time, as forceful rather than passive, it would mean that the perceiver views the target as quite assertive (descriptive level) but evaluatively neutral, the negative valence of aggressive being neutralized by the positive valence of forceful. However this rationale does not hold if aggressive represents -OP and forceful +SP. There is not only the problem of comparing apples and oranges, but, at least in some studies, the combination of -OP with +SP has been found to result in more extreme negative evaluations (e.g., Peeters, 1992; Vonk, 1996, but not in De Bruin & Van Lange, 199a, 199b and Peeters, 2004b), .This means that, at least in certain conditions, the impression formed of a target described as aggressive and forceful may be very negative rather than neutral. Third, it is possible now to reinterpret Peabody's findings regarding stereotypes in terms of SP and OP. For instance, Peabody found that northern nations were stereotyped as tight, while southern nations as loose. This means that the positive side of Northerners is perceived as +SP, and the negative side as -AP. In addition, both north and south European nations were found to be perceived as quite assertive, which means +SP. Altogether, this means that all European nations are perceived as quite +SP, the northern nations even more than the southern nations, but the southern nations are more unconditionally perceived as +OP. Considering that SP and OP values have been connected with social motivational value orientations (Peeters, 1983), the northerners' stereotype can be characterized as most individualistic, leaning towards competition, and the southerners' stereotype as individualistic as well, but less than the northerners, and leaning towards cooperation. In terms of stereotype content types (Phalet & Poppe, 1997; Fiske et al., 2002), this means that northern stereotypes reflect the "winner" type, and the "sinful" rather than the "virtuous" winner type (Phalet & Poppe, 1997) or, in terms of Fiske et al. (2002), prejudices marked by admiration and envy. The southern stereotype reflects the "virtuous winner" type, though less a winner than in the northern stereotype, which may correspond to prejudices that, if they deviate from admiration, become paternalistic rather than envious. 3.4. From Individual Profitability to Social Utility In this section I discuss the connections of SP and OP with the concepts of social utility and desirability developed by Beauvois and Dubois and investigated by many French colleagues I will refer to as the French School. Unfortunately most of the research of the French school has 10 been published in French, but recent English sources are Dubois (2003, and this symposium), and Dubois & Beauvois (2005). In this approach, "social utility" of a trait has been conceived as "potentially good-bad for society", being assumed that the possessor of the trait is a member of society. In this respect "social" utility of a trait might be called "societal" utility. It is distinguished from "social desirability" conceived as "good-bad for the other individual involved with the possessor of the trait in an interpersonal relationship". As to the content of the traits involved, "social utility" covers SP, and "social desirability" covers OP (Dubois, this symposium). This means that what is good (versus bad) for the self would also be good (versus bad) for society. However, what is good (versus bad) for the individual other one deals with is not necessarily so for society. A smart person who is able to achieve his or her goals and to make a successful career is assumed to have a great potential of social utility, which a nice and friendly baby has not. The nice and friendly baby is not marked with social utility but with "social desirability". In this way one and the same person (Churchill?) can be detested as a bully and, at the same time, be liked as a competent leader, a blessing to society. While the French school seems to have departed from a societal perspective, I conceived SP and OP departing from an individual-oriented perspective. SP of a trait means "good-bad for the individual possessor of the trait", and OP means "good-bad for the individual other who is dealing with the possessor of the trait". However, when running research, I obtained some results that might fit the societal perspective better than the individual-oriented perspective. For instance, in a study yet mentioned (Peeters, 1993), I was surprised to find positive national stereotypes marked by +SP rather than +OP. As explained above, I initially looked for an explanation in terms of artifacts due to translation errors. However, this explanation being dismissed (section 1.3), a plausible explanation may be that positive stereotypes of nations are marked by social utility rather than by individual-oriented profitability. Another unexpected finding was that when perceivers were informed that "A (dis)likes B", they did not attribute +(-)OP or (dis)likableness to B. At least they did not so when perceived or assumed reciprocation of the (dis)liking relation by B was controlled by the experimenter. Instead perceivers attributed more +SP to B if B was liked than if B was disliked. (Peeters, 1983). In line with the adage that "power is sexy", agency seemed to outrival communion as an attractive attribute of others. Thus taking the societal perspective one could argue that A (dis)likes B because of B's high (vs. low) potential of social utility. However, that wasn't my rationale. Considering that the amount of agency associated with liking the self exceeded by far the amount associated with being liked by an other, I explained also the latter agency as a form of "profitability to the self". Specifically I considered that it was most profitable to the self if one was able to get him/herself liked by others, even by others one dislikes. Indeed, it would mean that one could obtain favors without having the cost of doing favors in return. At the same time, being disliked by the others one likes would involve negative profitability because one might do favors to others without getting anything in return. The latter example illustrates how easy it is to construe societal and individual-oriented explanations accounting for the same data. It may indicate that the old psychological distinction between interpersonal and intergroup perspectives (Tajfel, 1978) applies to agency as well. As a matter of fact, it is not difficult to imagine that a high agency potential cannot only be used for the benefit of society but for the own benefit as well. Thus agency may be looked at from both the perspective of societal utility and the perspective of individual profitability. Both perspectives 11 may converge in that what's good for society is (often) also good for the self. Actually further research may be planned to trace possible differences. Perhaps it will be found that particular traits or aspects of agency are perceived as more profitable to the self than utile to society, while the reverse may hold for other traits. The duality of societal and individual perspectives may apply to OP as well. The literature on social dilemmas contains ample evidence that individuals are not always willing to use their social utility potential for the benefit of society but that they often give priority to the own individual profit. Which choice they make may be a matter of communion, which means: of OP, or social desirability. Hence I suggest not to have communion (OP, social desirability) confined to the individual-oriented perspective but to consider a societal variant as well. In sum, considering also the inverse relationship between the OP value of stereotypes and perceived conflict with the stereotyped target (see section 1.3), communion may be associated with perceived prosocial versus antisocial intentions. Thereby intentions associated with some specific communal traits may be perceived as more relevant for society than for other individuals, while intentions associated with other specific communal traits may be perceived as most relevant for other individuals involved in interpersonal relationships with the possessors of the traits. In this respect, Trafimow & Trafimow's (1999) Kantian distinction between traits reflecting perfect duties (honest, loyal) and traits reflecting imperfect duties (friendly, charitable) may be apply. A wild but tempting hypothesis may be that the perfect-duty traits reflect more societal communion than the imperfect-duty traits, the latter reflecting more the individual-oriented communion. Indeed, in comparison with the information that a person is friendly and charitable, the information that a person is honest and loyal may be perceived as a better indicator that the person will use his or her agentic potential in a way that is beneficial to society as a whole. Friendliness and charity, then, would be associated more with a perceived disposition to use one's agentic potential in a way that is beneficial to the individuals one encounters such as neighbors, a beggar in the street, and so forth. 12 References Benveniste, E. (1966). Problèmes de linguistique générale. Paris: Gallimard. Bos, K. (2005). Stability of self-profitability and other-profitability of descriptions in words and pictures. (Internal Report No 32). Leuven: K.U.Leuven, Laboratorium vooe Experimentele Sociale Psychologie. Child, I.L., & Doob, L.W. (1943). Factors determining national stereotypes. Journal of Social Psychology, 17, 203-219. Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of a theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press. De Boeck, P., & Claeys, W. (1988). What do people tell us anout their personality when they are freed from the personality inventory format. Paper presented at the 14th European Conference on Personality. Stockholm. De Bruin, E.N.M. (1999). Good for you or good for me? Interpersonal consequences of personality characteristics. (Doctoral dissertation published in the Kurt Lewin Institute Dissertation Series). Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit. De Bruin, E.N.M., & Van Lange, P.A.M. (199a). Impression formation and cooperative behavior. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29, 305-328. De Bruin, E.N.M., & Van Lange, P.A.M. (199b). The double meaning of a single act: Influences of the perceiver and the perceived on cooperative behavior. European Journal Personality,13, 165-182. Dubois, N. (Ed.)(2003). A sociocognitive approach to social norms. London: Routledge. Dubois, N., & Beauvois, J.-L. (2005). Normativeness and individualism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 123-146. Fiske, S.T., Cuddy, A.J.C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and Warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 878-902. Martin, I & Levey, A.B. (1987). 'Learning what will Happen Next: Conditioning, Evaluation, and Cognitive Processes'. In: G. Davey (red.), Cognitive Processes and Pavlovian Conditioning. Chichester: Wiley, p.57-81. Peabody, D. (1985). National characteristics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Peeters, G. (1983). Relational and informational patterns in social cognition. In W. Doise & S. Moscovici (Eds.), Current issues in European social psychology (pp. 201-237). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Peeters, G. (1986). Good and evil as softwares of the brain: On psychological 'immediates' underlying the metaphysical 'ultimates'. A contribution from cognitive social psychology and semantic differential research. Ultimate Reality and Meaning. Interdisciplinary Studies in the Philosophy of Understanding, 9, 210-231. Peeters, G. (1992). Evaluative Meanings of Adjectives in Vitro and in Context: Some Implications and Practical Consequences of Positive-Negative Asymmetry and Behavioral-Adaptive Concepts of Evaluation. 13 Psychologica Belgica 32:211-231. Peeters; G. (1993). Self-other anchored evaluations of national stereotypes. Internal Report No 5. Leuven: K.U.Leuven, Laboratorium voor Experimentele Sociale Psychologie. Peeters, G. (1995). What's negative about hatred and positive about love? On negation in cognition, affect and behavior. In H.C.M. de Swart & L.J.M. Bergmans (eds.), Perspectives on negation. Essays in honor of Johan J. de Iongh on his 80th Birthday -- Perspectives sur la négation. Hommage à Johan J. de Iongh pour son 80e anniversaire (pp. 123-133). Tilburg: Tilburg University Press. Peeters, G. (2001a). Self- and other-profitability values of American trait adjectives. Internal Report No 30. Leuven: K.U.Leuven, Laboratorium voor Experimentele Sociale Psychologie. Peeters, G. (2001b). In search for a social-behavioral approach-avoidance dimension associated with evaluative trait meanings. Psychologica Belgica, 41, 187-203. Peeters, G. (2003). The dual role of evaluative meaning as an incentive and an expression of behavioral approach and avoidance. Communication held at the 5th Meeting of the European Social Cognition Network. Padova, Italy, September 4-7, 2003.Peeters, G. (2004). Thinking in the third person: A mark of expertness?. Psychologica Belgica, 44, 249267. Peeters, G.,Amatulli, M.A.C., & Serino,C. (1998). Self- and other-profitability values of Italian trait adjectives. Internal Report No 21. Leuven: K.U.Leuven, Laboratorium voor Experimentele Sociale Psychologie. Peeters, G., Cornelissen, I., & Pandelaere, M. (2003). Approach-avoidance values of target-directed behaviors elicited by target-traits: The role of evaluative trait dimensions. Current Psychology Letters, 11, Vol. 2, http://cpl.revues.org/document396.html Phalet, K., & Poppe, E. (1997). Competence and morality dimensions of national and ethnic stereotypes: A study in six Eastern-European countries. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27, 703-723. Tajfel, H., Ed. (1978). Differentiation between social groups. Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. London: Academic Press. Trafimow, D., & Trafimow, S. (1999). Mapping imperfect and perfect duties onto hierarchically and partially restrictive trait dimensions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 686-695. Vonk R. 1996. Negativity and potency effects in impression formation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 26, 851-865. Wentura D, Rothermund K, Bak P. 2000. Automatic vigilance: The attention-grabbing power of approachand avoidance-related social information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 1024-1037. White, G.M. (1980). 'Conceptual Universals in Interpersonal Language'. American Anthropologist 82:759-781. Wojciszke, B. (2005). Morality and competence in person and self-perception. European Review of Social Psychology, 16, 155-188. 14 -----------------------------------------------------------------------------AMERICAN (from Peeters, 2001) +SP: ambitious, independent, persuasive, powerful -SP: ambitionless, dependent, naive, unmethodical +OP: friendly, generous, sympathizing, tolerant -OP: discriminating, greedy, selfish, unreliable -----------------------------------------------------------------------------ITALIAN (from Peeters, Amatulli, & Serino, 1998). +SP: brillante (brilliant), diplomatico (diplomatic), intelligente (intelligent), punctuale (punctual) -SP: esitante (hesitating), ignorante (ignorant), presuntuoso (presumptuous), timido (shy) +OP: disponibile (available), generoso (generous), sensibile (sensitive), affidabile (trustworthy) -OP: aggressivo (aggressive), autoritario (authoritarian), egoista (egoist), insensibile (insensitive) -----------------------------------------------------------------------------FLEMISH-DUTCH (Standard sets from Peeters, 1992) +SP: machtig (powerful), ambitieus (ambitious), zelfverzekerd (self-confident), praktisch (practical), vlug (quick) -SP: zwak (weak), ambitieloos (ambitionless), schuchter (shy), onhandig (clumsy), traag (slow) +OP: verdraagzaam (tolerant), edelmoedig (generous), gevoelig (sensitive), betrouwbaar (reliable), vertrouwend (trusting) -OP: onverdraagzaam (intolerant), zelfzuchtig (selfish), gevoelloos (insensitive), onbetrouwbaar (unreliable), achterdochtig (suspicious) -----------------------------------------------------------------------------ALTERNATIVE FLEMISH-DUTCH (Parallel sets drawn from De Boeck & Claeys (1988). +SP: zelfstandig, wil iets bereiken, spitsvondig, leergierig, heeft inzicht -SP: onzeker, vlug ontgoocheld, met zichzelf in de knoop, verstrooid, inspiratieloos +OP: behulpzaam, vergevingsgezind, rechtvaardig, zacht, meevoelend -OP: afbrekend, niet medevoelend, koel uit de hoogte, vindt andere mensen vaak niet de moeite waard, houdt ze op een afstand ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Schema 1. Sets of positive and negative SP and OP key traits from the American, FlemishDutch and Italian language-culture communities 15 Table 1 SP and OP values of 16 stereotypes (rows) from Child & Doob (1943) based on SP and OP judgments of the original stereotype traits by native American judges (AMER), of Flemish-Dutch translations of the traits by native Flemish judges (FLEM), and of Italian translations of the traits by native Italian judges (ITAL). ---------------------------------------------------------------Stereotyped Nations SP values OP values ------------------ ------------------ AMER. AMER. FLEM. ITAL. FLEM. ITAL. ------------------------------------------a b c d e f ---------------------------------------------------------------AMERICA 1938 41 30 35 23 07 29 1940 42 29 36 26 09 31 ENGLAND 1938 42 29 36 26 09 32 1940 41 28 35 26 09 31 1938 33 22 28 17 03 20 1940 37 24 33 22 07 26 GERMANY 1938 35 26 28 13 01 21 1940 37 26 30 17 04 24 1938 33 24 22 12 -02 14 1940 33 21 25 18 03 18 1938 31 23 19 07 -06 12 1940 33 24 23 13 00 17 1938 21 14 15 10 00 13 1940 22 13 16 14 03 16 1938 25 20 15 -02 -09 10 1940 20 17 06 -06 -11 06 FRANCE ITALY JAPAN POLAND RUSSIA ---------------------------------------------------------rab = .95 rde = .98 rac = .96 rdf = .94 rbc = .85 ref = .94 ---------------------------------------------------------- 16 Table 2 Correlations of average values (SP or OP) of n groups of k randomly selected American traits obtained from native American judges with the average values of Italian translations of the traits obtained from native Italian judges. -----------------------------------------------------------SP OP ----------------- --------------k=1 n=120 .71 .82 k=2 n=60 .67 .82 k=3 n=40 .66 .77 k=4 n=30 .63 .82 k=5 n=24 .58 .81 k=6 n=20 .63 .75 k=8 n=15 .25 .68 k=10 n=12 .71 .83 k=12 n=10 .42 .86 ---------------------------------------------------------------Note. k = number of traits per group; n = number of groups 17 Table 3(a) Traits representing the descriptive dimension "tight-loose" with general valence according to Peabody (1985), expected and obtained OP and SP values, and results of contrast analysis testing the agreement between the expected and obtained contrasts. --------------------------------------------------------------TOO OPTIMALLY OPTIMALLY TOO TIGHT TIGHT LOOSE LOOSE --------------------------------------------------------------stingy inhibited grim distrustful severe inflexible choosy thrifty self-controlled serious skeptical firm persistent selective generous spontaneous gay trusting lenient flexible broad-minded extravagant impulsive frivolous gullible lax vacillating undiscriminating --------------------------------------------------------------VALENCE Peabody: - OP* expected: obtained: -1.43 + + - 0 +0.43 + +1.71 0 -0.29 SP** expected: 0 + 0 obtained: +0.36 +0.68 +0.21 -0.93 --------------------------------------------------------------*OP contrast: F(1,24) = 67.56 p < .0001 MSE = 0.52 **SP contrast: F(1,24) = 06.84 p < .016 MSE = 1.32 ---------------------------------------------------------------- 18 Table 3(b) Traits representing the descriptive dimension "assertive-unassertive" with general valence according to Peabody (1985), expected and obtained OP and SP values, and results of contrast analysis testing the agreement between the expected and obtained contrasts. --------------------------------------------------------------TOO OPTIMALLY OPTIMALLY TOO ASSERT. ASSERT. UNASSERT. UNASSERT. --------------------------------------------------------------aggressive conceited forceful self-confident peaceful modest passive unassured --------------------------------------------------------------VALENCE Peabody: - + + - OP* expected: obtained: -1.88 0 +0.38 + +1.75 0 -0.38 SP** expected: 0 + 0 obtained: +1.12 +2.62 -0.62 -2.50 --------------------------------------------------------------*OP contrast: F(1,4) = 13.14 p < .0015 MSE = 0.21 **SP contrast: F(1,4) = 480.29 p < .0001 MSE = 0.05 ---------------------------------------------------------------- 19