The stability of grazing systems

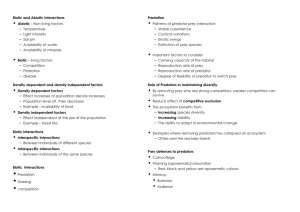

advertisement

February 11, 2004 The stability of grazing systems - overview 1. Is grazing a problem to plants? No, plants are eaten all the time, they have evolved numerous mechanisms to persist in the face of continuous predator attack (indeterminant growth, low palatability, toxins, tree-form, predation-safe storage, spines …) At the same time, predators have co-evolved to get around some of the obstacles (toxin tolerance, new digestive abilities, skills or morphologies to get to hidden plant parts, …). Naturally evolved grazing systems tend to be quite diverse. 2. What sort of ecological mechanisms maintain species diversity? In the most general sense, diversity is maintained if there are mechanisms that limit species growth when they are abundant (have high density) and foster species growth when they are rare (have low density). These feedback mechanisms have to work on all species in the community. One of the most important mechanisms is the differentiation of species by the ecological niches they occupy, i.e. by their differences in resource use. Because species tend to be restricted to their niches, and because different species have different niches, species tend to suppress themselves the most when they are abundant, rather than drive other species to extinction. On the other hand, when a species is rare, its niche is relatively empty and it can achieve very high growth rates when conditions are good. Grazers and other predators also help to maintain diversity: Behaviorally: predators tend to select species that are more abundant and ignore rare species. Through population growth responses: High abundance in one plant species tends to increase the birth rates of its predators. Eventually, the higher number of predators reduces plant density. Conversely, when a species is rare, its predators also tend to even rarer. There are many other conceivable feedback mechanisms that help to put bounds on population growth and help species at low density to recover: Fire could set back dominant grasses and give rare grasses a chance to recover, disease spreads faster in populations at high density than at low density, free-ranging grazers migrate from regions of low forage abundance to regions of higher abundance, top predators check the population density of grazers, which could limit overgrazing by hungry animals. 3. Do some of these feedback mechanisms break down in man-managed grazing systems? There may be a lack of feedback control on alien plants that have not co-evolved with indigenous species, both plant and animals (e.g. fewer natural enemies, broader niches). February 11, 2004 Equally, there could be a lack of feedback control on alien grazers: grazer densities could be held artificially high by supplementary feeding and installation of water sources. Plants may be intolerant to the way alien animals graze. Top predator elimation could reduce control over indigenous plant-eaters. Fences limit migratory movements, predominantly of the managed grazers. Reseeding with competitively superior monocultures may swamp out natural population control in the vegetation (through intra- and interspecific competition). Fire suppression could weaken suppression of dominant species. 4. What is the actual evidence that the introduction of cattle and sheep grazing changes plant communities? Evidence is hard to come by, because diversity may have been lost before anybody paid attention. Areas never grazed may be different for other reasons. Changes in vegetation released from grazing may be different than changes associated with firsttime cattle/sheep grazing. In an Australian study long-term exposure to grazing was assumed to vary with distance from the well. The study found that a) there are many rare species, b) more of the rare species are found furthest away from the well than close to it, c) most alien species increased in abundance with proximity to the well. The analysis of packrat middens from Utah indicates a major shift in vegetation in the past 200 years: severe reduction in vegetation that grazers like to eat, severe reduction too in other species that are not so good to eat. Other species were rare 200 years ago, but are abundant now, some of them exotics, some not. Overall, it is possible, but ultimately unproven, that some species that were rare before cattle/sheep grazing went locally extinct on rangelands. It is certain that major shifts in species dominance occurred, and that overall vegetation cover declined.