LAB 3 lithic technology handout

advertisement

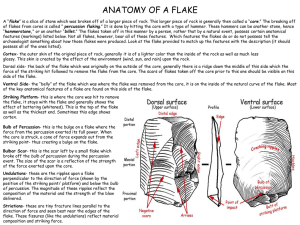

Anth 140 Summer 2007 Raw materials: Lithic, or chipped stone tools can be made only from a few specific types of rock, all of which are composed largely of silica (SiO2). These rocks are either amorphous, meaning that the minerals that compose the rocks have not formed crystals, or cryptocrystalline, meaning that the minerals have formed patterns of microscopic crystals. Because these rocks are not composed of large crystalline minerals, they break much like common glass, yielding conchoidal fractures. A conchoidal fracture is one in which the fracture surfaces are curved. When the rock is struck the energy of the blow is distributed evenly, in a radial fashion, away from the point of contact. This property of fracturing conchoidally is what makes the production of lithic tools possible. Definitions: The practice of producing lithic tools is generally termed flintknapping. Initially, a stone, called the core, is struck, to break off smaller pieces, the flakes. Depending on the technology of the flintknapper, either the core or a flake may then be worked into a finished tool. The flat surface at the top of the flake where it was struck is called the platform. The platform end is the proximal end of the flake; the end where the flake terminates is the distal end. The interior surface of a flake, i.e. the surface that was next to the core, is called the ventral surface; the exterior surface is called the dorsal surface. Concave surfaces on any stone where flakes have been removed are called flake scars. Any of the original weathered surface of the stone remaining on the flakes or core is called cortex. The waste products of flintknapping, including unwanted flakes, are called debitage. Courtesy of: http://www.utexas.edu/courses/denbow/labs/lithic2.htm Anth 140 Summer 2006 Techniques: Due to conchoidal fracture properties, flakes and cores tend to have distinctive characteristics that vary with the flintknapping techniques used to produce them. The three most common techniques are (1) hard hammer percussion, (2) soft hammer percussion, and (3) pressure flaking. Hard hammer percussion is the earliest and most basic flintknapping technique, producing flakes by striking another stone, the hammerstone, against a core. It can be used to produce finished, but simple, lithic tools from cores, such as the early handaxes used by Homo erectus, or as a starting point for more elaborate tools formed either from cores or flakes. A flake struck using hard hammer percussion frequently has a crushed area on the platform called a point of percussion. Beneath this on the interior surface of the flake, there will be a swelling, called the bulb of percussion, caused by the force of the striking blow. Beneath the bulb of percussion, the force of the blow may have created ripples in the fracture which center around the bulb of percussion. Courtesy of: http://www.utexas.edu/courses/denbow/labs/lithic2.htm Anth 140 Summer 2006 Soft hammer percussion produces flakes by striking the unfinished tool with a soft hammer, usually a piece of antler, bone, or wood. A soft hammer flake differs from a hard hammer flake in that it tends to be thin and flat with a small platform, a lip on the interior of the platform, and a low diffuse bulb of percussion. Because soft hammer percussion is the easiest way to remove large, thin flakes, is particularly useful in producing thin bifaces, or lithic tools that have been flaked on both sides. Pressure flaking produces flakes by using a flaker made of a soft material, such as antler, bone, wood, or copper to apply force by pressing rather than striking. Pressure flakes are small and fragile, and are used to thin and shape lithic tools. Many lithic tools are produced by a combination of all three techniques, with hard hammer percussion followed by soft hammer percussion and then finished by pressure flaking. Courtesy of: http://www.utexas.edu/courses/denbow/labs/lithic2.htm