António Manuel Hespanha & Teresa Pizarro Beleza

advertisement

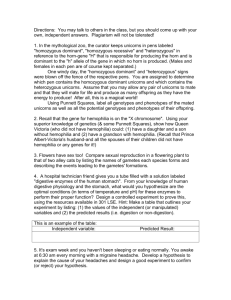

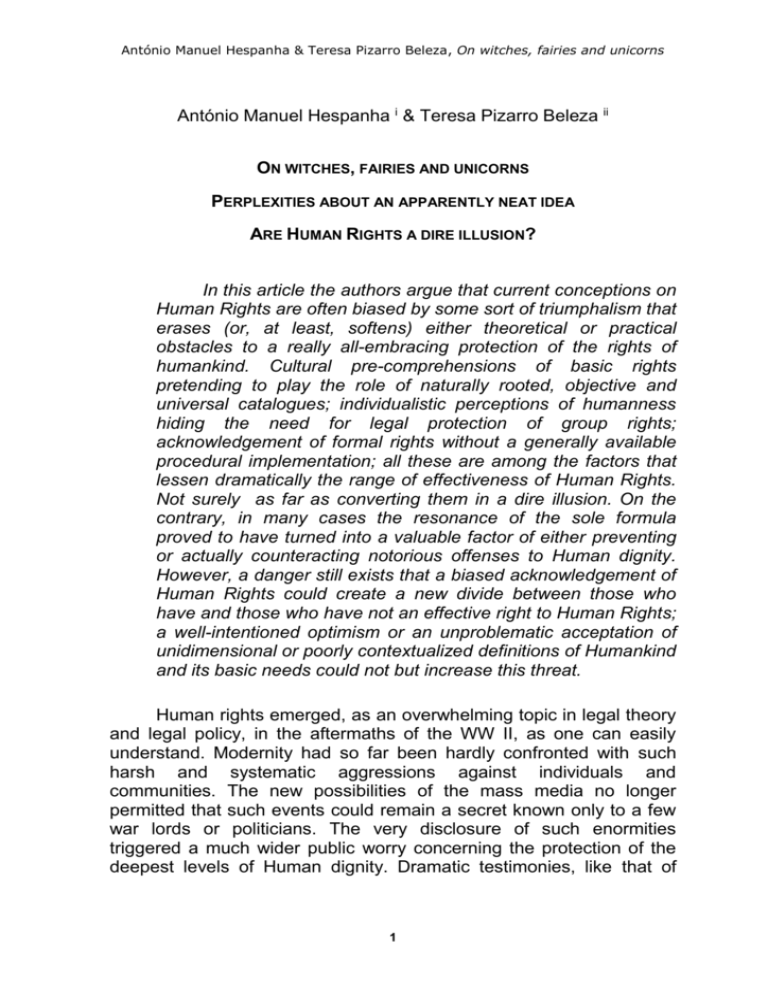

António Manuel Hespanha & Teresa Pizarro Beleza, On witches, fairies and unicorns António Manuel Hespanha i & Teresa Pizarro Beleza ii ON WITCHES, FAIRIES AND UNICORNS PERPLEXITIES ABOUT AN APPARENTLY NEAT IDEA ARE HUMAN RIGHTS A DIRE ILLUSION? In this article the authors argue that current conceptions on Human Rights are often biased by some sort of triumphalism that erases (or, at least, softens) either theoretical or practical obstacles to a really all-embracing protection of the rights of humankind. Cultural pre-comprehensions of basic rights pretending to play the role of naturally rooted, objective and universal catalogues; individualistic perceptions of humanness hiding the need for legal protection of group rights; acknowledgement of formal rights without a generally available procedural implementation; all these are among the factors that lessen dramatically the range of effectiveness of Human Rights. Not surely as far as converting them in a dire illusion. On the contrary, in many cases the resonance of the sole formula proved to have turned into a valuable factor of either preventing or actually counteracting notorious offenses to Human dignity. However, a danger still exists that a biased acknowledgement of Human Rights could create a new divide between those who have and those who have not an effective right to Human Rights; a well-intentioned optimism or an unproblematic acceptation of unidimensional or poorly contextualized definitions of Humankind and its basic needs could not but increase this threat. Human rights emerged, as an overwhelming topic in legal theory and legal policy, in the aftermaths of the WW II, as one can easily understand. Modernity had so far been hardly confronted with such harsh and systematic aggressions against individuals and communities. The new possibilities of the mass media no longer permitted that such events could remain a secret known only to a few war lords or politicians. The very disclosure of such enormities triggered a much wider public worry concerning the protection of the deepest levels of Human dignity. Dramatic testimonies, like that of 1 António Manuel Hespanha & Teresa Pizarro Beleza, On witches, fairies and unicorns Primo Levi 1, or Jorge Semprun 2 made of the most simple, but also the most pungent, fragments of the everyday life in an extermination camp, exposed how much human life, even if preserved, can be turned into something totally deprived from the most basic features of being Human. These ordinary propositions immediately entail the need for a few remarks, in order to deepen the analysis of what really brew his new sensitivity to the issue of Human Rights. A first remark shall underline that the magnitude of the Shoa, as well as of the extermination of gypsies, homosexuals and other “undesirables”, or even that of the Nazi genetic cleansing of handicapped people, often leads to the oblivion that brutal attacks on Human Rights were of course not new in the very Modernity. Each new tragedy, natural or man-made, tends to efface the immediate memories of what terrible things happened before. Almost equivalent atrocities were already committed, mostly under colonial rule, on nonEuropean native populations. Two of the most notorious examples will be enough to illustrate our point. The first one is the passivity – to say the least - of British government in India during the outburst of famines in Central India, between 1870 and 1910; then, more than thirty million famine related deaths occurred, in a process where natural factors combined with a seemingly intentional policy of ethnic / eugenic extermination, which deserved recently the denomination of “Late Victorian Holocaust” 3. The second one is the German genocidal war against the Herero, in South West Africa, by the end of the 19th century, during which 80 percent of the Herero died or were incarcerated to die in concentration camps; an explicit “order of extermination” (Vernichtungsbefehl) against the Herero people was issued in October 1904, inaugurating a terminology and a practice which announce and prepare what would come true in continental Europe within a few decades4. Even if we leave aside for the moment the reference to Human Rights violations in the particularly callous colonial underworld, we are still left with some other examples of rather gruesome and ruthless treatment of ethnic, religious and cultural groups in the near peripheries of “civilized nations” 5. Even in the core 1 Se questo è un uomo, Torino, De Silva, 1947. 2 Le grand voyage, Paris, Galimard, 1963; Quel beau dimanche, 1980; L'écriture ou la vie, 1994. 3 Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World, London, Verso, 2001. S. other references in Laxman D. Satya, ”The British Empire, Ecology and Famines in Late 19th Century Central India”, Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania (http://www.celdf.org/Portals/0/Docs/NATURE%20and%20EMPIRE%20%20LAXMAN%20SATYA%20ARTICLE%20ON%20BRITISH%20EMPIRE%20ECOLOGY%20FAMINE%20IN%20INDIA.doc). 4 A similar fate struck the Nama population some years later. 5 Even today, Turkish official historiography refuses to classify the massive extermination of Armenian as a genocide. 2 António Manuel Hespanha & Teresa Pizarro Beleza, On witches, fairies and unicorns of western supposedly decent people (USA, UK, Sweden, Russia), “progressive” policies developed “eugenic” programs and practices which today would surely fall within the concept of serious violations of Human Rights . One need only think of the data on domestic violence and go back to the isolated denunciations of Stuart Mill in the British Parliament in Victorian times to understand that in the core of “civilized” nations basic Human Rights of many people, in particular women and children, were violated as a matter of course under the supposed sanctity of privacy and home. And, of course, the violence continues – but not silenced and accepted as before, when laws and customs shielded the horrors of family and domestic terror. To remember these histories is no merely historical exercise. It can also lively enlighten some current imbalances in the pervasive feelings about Human Rights, their nature, their range and their typical victims and predators. First of all, recent history can unveil the unspoken reasons which lead to differentiate the relevance of these primary rights according to the geographic and ethnic-cultural scenario where their offence takes place. Namely, in differentiating the cogency and urgency of rights of mankind and human beings, as well as in conceiving and implementing systems of protection, respectively either – let us say – in the so called “civilized countries” or, by contrast, in the “waste lands” of Africa and of some regions of Asia or Latin America. While the former occupy the leading titles and the prime time TV journals, the second latter are almost completely “lost in translation”, trivialized or merely kept out of public memory. One could say that even Human Rights tend to gain a geographical milieu of their own. Secondly, the most recent history seems to demonstrate that the most repulsive violations of Human Rights tend to be committed, not against individuals, but against groups, characterized by their ethnicity, religion, culture, customs, way of life, or gender. It is morally true than Human dignity is not measurable, in the sense that the offense against one person is, ethically speaking, as serious as the offense against very many. However, our moral sensitiveness is also affected by the sheer number of victims of harm, so much so that ordinary language has coined a specific word, genocide which expresses more vehemently the common repugnance towards a massive and collective offense of Human Rights (contrasting with homicide, which ordinarily is not deemed to be, per se, either a crime against humanity, or an autonomous and specific offense of Human Rights, but rather as a 3 António Manuel Hespanha & Teresa Pizarro Beleza, On witches, fairies and unicorns “common crime”, however serious). Ordinary moral sensitiveness seems to be rather communitarian than individualistic, evaluating under much darker tones the harm caused to humans - i.e., to a collective of beings belonging to the larger collective of mankind - than that caused to an individual. Thirdly, in some of the more recent historical examples of deep and serious contempt towards Human Rights, the State was involved, as they were either carried out directly by State organs or allowed to happen due to State administration (intentional) carelessness or callous ignorance of a “duty to protect”. However, beyond or behind the State was civil society, or even particularly influential and celebrated groups within it. Namely, scientist, who - from the 1880’s to the 1940’s – created a whole set of theoretical topics legitimating human differentiation, human hierarchies and human divisions along the lines of normality/abnormality, mostly within scientific disciplines like Anthropology and Eugenics 6. Occasionally – as it often happened in the colonies – there was a perceptible, although silent, congeniality between “scientific” and economic or political interests. This means that every strategy to protect Human Rights should discard a Stateonly oriented approach in order to adopt a wide and all-embracing checking and watching strategy, scanning every potential predator of humankind, including possibly well intentioned policies aiming at the bettering of human condition and human life quality. Summing up. Narrow, imprudent or group biased utilitarianism can clash with major rights of individuals or communities, even if it is labeled under a humanitarian telos. Fourthly, it must be stressed – as we can learn from the examples above - that almost all human tragedies are the product of active or passive policies and not of mere natural causes. Famine can normally be foreseen, prevented, or at least reduced ; physical or psychic challenges or imbalances can be accepted as normal differences or compensated for through measures compatible with Human dignity; environmental disasters can often be avoided by adequate policies or drastic, but prudent, changes in the way of life. Nature is seldom independent from human political decisions, let alone the everlasting attempt to transform nature into a scapegoat for human 7 6 S. Edwin Black, War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America's Campaign to Create a Master Race, Four Walls Eight Windows, 2003; Gina Maranto, Quest for Perfection: The Drive to Breed Better Human Beings, Diane Publishing Co., 1996; Universe.com, 2000; Richard Lynn, Eugenics: a reassessment, Praeger Publishers, 2001. 7 Amartya Sen, “Democracy Isn't 'Western'”, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB114317114522207183.html?mod=opinion_main_commentaries. 4 in António Manuel Hespanha & Teresa Pizarro Beleza, On witches, fairies and unicorns errors, carelessness or greed. This consideration is particularly important as we are apparently entering a period of rough environmental changes, which will very likely have devastating effects on human life. A great deal of this imminent danger is the result of human/societal decisions about producing goods and providing services (what, how, how much and at what costs) and, in the end, about keeping or changing living styles. Environmental threats can be anticipated and curtailed by restraining damaging policies and styles of living, by reducing avoidable risks, by subsuming secondary goals to the paramount value of preserving all embracing humankind’s future, by improving solidarity and implementing an ethic of care. “Caring for the Future 8” must be a political priority here and now. To imprudently or impudently jeopardize the future can only be described as a threat or a real offense to Human Rights. This dramatic shift in human environment should certainly soon lead to an emergent age of Human Rights protection, which should be more demanding, more global and more thoroughly protective. From now on, amidst the indicted people on judicial cases of Human Rights violations, brutal war lords and dictators will share their notorious arena with greedy or sloppy politicians, tycoons, or other representatives of egoistic (nationalistic, regionalist, sectorial) interests. Finally, we shall address a last question which, can be more clearly perceived today than a century ago. It is now easy enough to understand that all the European world policy along the last decades of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century was supported by a deep rooted ethnocentrism, if not by an outright, entrenched pervasive racism and sexism. This may help to explain the low sensitivity of both politicians and in general of discourse in the public sphere regarding the atrocities perpetrated against non-European people. Or the subjection and violence against women, which became a public issue only fifteen years ago 9. Ethnocentrism may also help to explain the absence of an audible critical approach to the values European nations were imposing over “alien” cultures. On the inner front, scientism provided the same dogmatic shield against otherness, be it gender differences, physical or psychic deviance or alternative strategies for organizing communitarian life. The European oriented uniqueness of humankind developed in a twofold way a strangely unidimensional mental model: 8 “Caring for the future” is the strategic guideline of a Portugal based Foundation, dealing with strategic issues concerning a sustained well being for the Human generations to come (http://www.fcuidarofuturo.com/cuidarofuturo.html). 9 The UN Declaration on Violence Against Women dates from 1993… 5 António Manuel Hespanha & Teresa Pizarro Beleza, On witches, fairies and unicorns the uniqueness of culture and the uniqueness of truth, values and mores. On the legal front, this uniqueness of European moral economy was expressed in the uniqueness of political power and the uniqueness of law, as it was theoretically built by both the legalism and the logical deductivism of the German Pandectistic, the two mainstreams of the European-continental legal model. These are in fact much more structurally influential in European legal culture than the episodic albeit long political authoritarianism, pervasive in the 1930’s and 1940’s. If such unidimensional legal thought was deemed to be a core component of the authoritarian regimes which carried out – in the 1930s and in the 1940s – the harshest violations of individual and collective Human Rights to this date 10, the fact is that the trend to uniqueness began long before and survived until long after the authoritarian wave. In common law countries this trend to legal uniqueness also had its surrogates, as the combination of Austin’s positivism with a narrow conception of realism, both of which rendered un-problematic either the native constituted legal values or their extension to other cultural environments. Therefore, the very definition of Human Rights was not completely freed from this unidimensional conception of humankind, human values, good government and – as a consequence – the herein derived rights of individuals or of groups. Even if we turn to the kind of jusnaturalism prevailing in southern Europe in the same period, which was deemed to be a better shelter for Human Rights, we have to admit that is was inoculated by the same unidimensionalism. Southern Euro-continental jusnaturalism was actually, mainly rooted in the social doctrine of the Catholic Church, namely in the Encyclic Aeterni Patris, issued in 1879 by Pope Leo XIII, which condemned all the symptoms of modernism (as “a plague of perverse opinions”), amidst them democracy, freedom of conscience, pluralism and Human Rights, insisting on a political society based on the “Authentic first principles”. Even some liberal Catholic thinkers (like Jacques Maritain) stated that the Church’s doctrine was compatible with most of the political regimes known on Earth, even those non democratic or elitist, as far as they respected the Catholic dogmatic understanding of the dignity of the Human Person 11. 10 Actually, the assumption of this linkage is a quite problematic the core of the authoritarian legal thought was almost always more dependent of a decisionistic than of a legalistic pattern of law. 11 Kenneth L. Grasso, “Democracy, Modernity and the Catholic Human Rights Revolution: Reflections on Christian Faith and Modern Democracy”, ttp://www.catholicsocialscientists.org/cssrIX/Kraynak%20symposium 6 António Manuel Hespanha & Teresa Pizarro Beleza, On witches, fairies and unicorns This ethnocentric conception of Human Rights can be read at a double level. On the one side, the offense of Human Rights was narrowly bound to an individualistic conception of rights, which excluded or made difficult the legal condemnation of offenses against groups or communities. “Everyone” and “No one” are systematically the incipit of every article of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). And it was to a large extent this limited conception of Human Rights that lead the UN to approve successive declarations of group rights, culminating, almost 60 years (!) after the San Francisco’s Charter, in a supplementary Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples12, where the collective side of the rights of mankind, hidden by the atomistic conception of society, is finally assumed, notwithstanding the predictable obstacles of their practical implementation in strict legal terms. That is corresponds to a specific European cultural element is possibly proven by the fact that the African Charter on Human Rights is less individualistic (rights of “peoples”) than the European Convention on Human Rights. On the other hand, values included in human nature that were recognized as needing protection were solely those embedded in the Western European elitarian culture, now taken as a universal canon . Not by chance, every right included in the most conspicuous Declarations and Charters was born in the womb of Western culture; notwithstanding the fact that Europeans had already “opened the world” and witnessed both several other ways of life and different sets of communitarian basic values. This ethnocentric concept of Human Rights provoked strong reactions from “exotic” cultures, societies and political entities. On the political arena, arguing and counter-arguing about Human Rights violations, moved from a political to an anthropological level. Mainland China, for example, left the prior arguments based on the “inner” nature of the question and the denegation of legitimacy of third Sates or organizations to interfere in issues depending on each State’s sovereignty, to adopt a brand new defense, anchored on the most influential Western anthropology or philosophy (namely, that of Clifford Geertz or Richard Rorty), when they assess values as “local” and embedded in cultural / political 13 12 Adopted by General Assembly Resolution 61/295 on 13 September 2007. On the violence which made possible sush homogeneization of Western European Culture, s. Zygmunt Bauman, Legislators and Interpreters: On Modernity, Post-Modernity and Intellectuals, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987 13 7 António Manuel Hespanha & Teresa Pizarro Beleza, On witches, fairies and unicorns contexts 14. On the theoretical arena, the issue of Human Rights and decent government gave origin to a lively worldwide debate on the peculiarity of local values, from the “Asian values”, which are deemed to frame conviviality from China to Singapore, India and Japan 15, to “African values”, which grounded a regional Charter of Human rights for Africa, approved in 1981 16. In face of this kind of criticism, are we forced to agree with Alistair MacIntyre, when he writes that to count on Human Rights as a source for normative projects is something akin to believe in witches, fairies and unicorns, which nobody has ever seen ? 17 A possible answer is that Human Rights can actually be seen as far as they are vested in ratified charters or enshrined in agreed international declarations. Although this prerequisite could be viewed as a pyrrhic victory, needing as it does the agreement of the States, it still brings a warrant of “local” social and political embeddeness and the resulting feasibility. Conversely, trying to escape from such realistic approach risks to embody, once again, a further attempt at (occasionally well intentioned) cultural colonialism, imposing as Human Rights expectations which are well rooted in our (European) political mores, but totally unexpected and even strongly irritating in different cultural contexts. Even if majorities are not parliamentary ones, however conspicuous enough 18 to be clearly distinguished from people’s manipulation, it seems wise to credit their political sensitiveness – at least provisional – a status of legitimacy, which prevent their disruption by an external counter-majoritarian 19 14 S., v.g., Julia Ching, “Human Rights: A Valid Chinese Concept?”, on the theoretical background of the Chinese White Paper ion Human Rights, 1991 [http://www.religiousconsultation.org/ching.htm]; also, Wang, Z. , 200901-07 "Historical Embeddedness and Endogenous Constraint: Re-examination of Relation between Sovereignty and Human Rights" Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Southern Political Science Association, Hotel Intercontinental, New Orleans, LA <Not Available>. 2009-05-22 from http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p283489_index.html; Stephen Angle, Human rights and Chinese thought: a cross cultural inquiry, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2002 max., 4/5, describing the evolution in the tone of Chinese White Papers on human rights; a broader panorama of Chinese and Western debate on the theoretical foundation of human rights, Marina Svenssons, Debating Human Rights in China: A Conceptual and Political History, Rowman & Littlefield, 2002. 15 S., v.g., Kishore Mahbubani, Can Asians think, Singapore, Steerforth Press, 2002. Discussing the idea of “Asian” values: Amartya Sen, "Human Rights and Asian Values," The New Republic, July 14-July 21, 1997 (http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/sen.htm). A SEN: The Argumentative Indian… 16 S. http://hdr.undp.org/en/reports/global/hdr2000/papers/MUTUA.pdf. 17 "Some Consequences of the Failure of the Enlightenment Project", After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory. University of Notre Dame Press, 1981. Actually, what MacIntyre was arguing was that it was impossible to demonstrate the existence of Human Rights without a reference to supra-positive levels of belief, like faith. 18 Although under other more or less credible forms of manifestation, like pervasive social consensus. 19 The counter-majoritarian fallacy was originally criticized by Alexander Bickel, The Least Dangerous Branch,1961, to denounce the imposition of pretended truth (or, at least, truthful) values to the values of representative assemblies, claimed as hazardous, self interest-seeking, emotional or populist. The comparison is appealing as “universal human rights” are also deemed to overcome irrationality, lack of cosmopolitism, deficits of civilization, shortage of human sensitiveness, political indecency. 8 António Manuel Hespanha & Teresa Pizarro Beleza, On witches, fairies and unicorns conception of good governance. Once rendered visible by the hegemonic / majoritarian native community, Human Rights should obey the geometry proper to this community. Delicate and extremely controversial issues may arise when locally rooted values damage the rights of particular groups within a local culture. This is typically the case of women in some Islamic communities, in orthodox Jewish groups or even in traditional Mediterranean societies. Often, the proper answer to the troubling question of Susan M. Okin, Is Multiculturalism Bad for Women? 20 shall definitely be “yes”. However, wisdom and caution are highly required by the diagnosis and the therapeutics in these critical areas of protecting rights which a rooted / hegemonic / majoritarian local culture does not acknowledge. Actually, the first need is a hermeneutical task, a thick interpretation of local attitudes, in order to uncover their deeply contextualized meaning, instead of hastily give them the meaning they have for us. Sometimes modesty, reserve of intimacy or sense of restraint are read as self-humiliation, serfdom or submission to external constraint; often, in spite of troubling but quite unequivocal signals, we don’t accept easily to consider that, in these uncomfortable cases, what is finally at stake is a different “anatomy of the soul” (as “strange” it may be). Also on the level of social therapeutics, experience is eloquent in telling us that a to hasty imposition of “correct” values and behaviors often triggers a violent social refusal and a consolidation of what would be to erase. Are we proposing a simple surrender of our convictions on Humanity and on its core values and rights ? Or even a seemingly hopeless expectation of spontaneous changes in the uncomfortable otherness ? Surely not. The deference to difference is also a deference for our own feelings of fairness. On the other hand, cultures are mobile and entangled artifacts, made up of conflicting perceptions and senses of belonging and identity. Subaltern groups within a culture do participate in several and often contradictory feelings of fairness, some arising from their unbalanced social position, others imported from external cultural sensitiveness. This intricate network of systems of values, with the inherent triggering of a political dialogue about confronting values, does introduce a real but autonomous dynamism in the group definition of good life and fair governance 21. Actually, the problem is similar to that recently raised by Karl-Heinz Ladeur with 20 Susan Moller Okin, “Is Multiculturalism Bad for Women?” in Joshua Cohen and Matthew Howard, Is Multiculturalism Bad For Women? Princeton University Press, 1999. 21 S. Amartya Sen, Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny (Issues of Our Time), New York, W. W. Norton Company, Inc., 2006. 9 António Manuel Hespanha & Teresa Pizarro Beleza, On witches, fairies and unicorns respect to the weighting (Abwägung) of conflicting legal values within a legal system 22; this has to be the outcome of an internal self-adjusting process producing the least irritating solution, instead of the result of an external adjudication jeopardizing generalized expectations. This process of autopoietic adjustment will surely take its time to reach an equilibrium. However, taking time can be more productive than forcing it; also here, indolence could be a wise way of capitalizing and making work social experience 23. A last couple of phrases about the scope and addressees of a legal shelter of Human Rights. Human Rights comprise all the expectations consistent with a conception of well being and well-ordered society – expectations towards the state, but also towards other social groups or individuals. Life is lived in many rooms (State, family, job, gender groups, very primary needs, to basic communicational requisites), each of one inhabited by specific dangers and threats. In some rooms, individual rights are required; in others, what a life worth being lived needs, is probably mutual duties of cooperation, “republican” solicitude and brotherly and sisterly compassion; in many, on the opposite, real public assistance and care are the main needs. Without the protection being afforded in each one of these living rooms, human life can be so severely amputated that it will no more merit the qualification of human, becoming eventually a residual “naked life” (G. Agamben), where the very sense of being human may be lost. Since the appeal to Human Rights is more than a programmatic or rhetorical proposition, it will only make sense where its force is doubled by an institutionalized procedural efficiency that can grant the availability of their implementation or defense to everybody, individuals or groups. This is a crucial issue, because the current legal rules usually design the jurisdiction proper to claim such rights as a highest jurisdiction, frequently dependent on unknown, foreign, far and expensive procedures, therefore almost inaccessible to ordinary people. The rationale seems to be either a symbolic one – the correspondence between the high rank of this kind of rights and the high level jurisdictional institution – or an idea inherited from the prior conception that the normal offender being the State, the jurisdictional control had to be outside the possibility of State control. 22 Boaventura Sousa Santos, A Crítica da Razão Indolente. Contra o desperdício da experiência, Vol. I, Edições Afrontamento, 2000. 23 K.-H. Ladeur, Kritik der Abwägung in der Grundrechtsdogmatik. Plädoyer für eine Erneuerung der liberalen Grundrechtstheorie, Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck, 2004. 10 António Manuel Hespanha & Teresa Pizarro Beleza, On witches, fairies and unicorns The result is that Human Rights, whose main feature is their ubiquity and pervasiveness, are only actionable by small elites, well informed, assisted by legal counsel, wealthy enough to afford a rather specialized and least known jurisdictional path. This may mean that some have seen the witches, the fairies and the unicorns; many more may have imagined them; but only a few have had the privilege to come near them and checked for real if they were more than a passing fancy. And yet, the banality of evil and the resistance of goodness might have engendered a denser population of realistic dreams. i Prof. at the Faculdade de Direito, Universidade Nova de Lisboa (amh@oniduo.pt) – Legal History, Theory of Law. ii Prof. at the Faculdade de Direito, Universidade Nova de Lisboa (tpb@fd.unl.pt) – Criminal Law, Human Rights Law, Gender Law. 11