Metaphor and denominative variation in science: A cognitive

advertisement

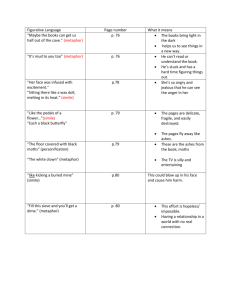

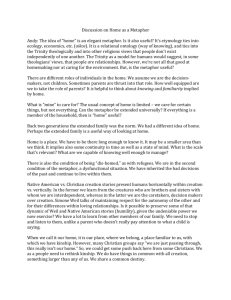

A cognitive sociolinguistic approach to metaphor and denominative variation: A case study of marine biology terms1 José Manuel Ureña Gómez-Moreno (University of Castile-La Mancha) Pamela Faber (University of Granada) This research applied corpus analysis techniques to a corpus of marine biology texts in Peninsular Spanish (PS) and Latin American Spanish (LAS). The results explain why these varieties of Spanish have different designations for the same sea organism. The focus of our research was thus on types of formal onomasiological variation (Geeraerts, Grondelaers & Bakema, 1994) and its pervasiveness in Spanish scientific discourse. Also addressed was the incidence of metaphor in specialized concept formation and designation. Domain-specific and standard strategies were used for the semi-automatic retrieval of metaphorical terms. The resulting qualitative and quantitative account of terminological diversity reflected the pervasiveness of intralingual denominative variation in scientific language and also identified its causes. Keywords: intralingual variation, cognitive sociolinguistics, metaphor Metaphor and denominative variation in science 2 1. Introduction Cognitive Sociolinguistics (e.g. Geeraerts, Kristiansen & Peirsman, 2010; Kristiansen & Dirven, 2008; Speelman, Grondelaers, & Geeraerts, 2003) is a field of research that focuses on the interaction of conceptual meaning and variational factors as reflected in the analysis of corpus data (Geeraerts et al., 2010, p. 1). This model draws on empirical methods to measure lexical-semantic as well as constructional language-internal variation. According to Geeraerts (2006, p. 30), language variation has been studied in Cognitive Linguistics and related disciplines from many perspectives: (i) a diachronic perspective (Bybee, 2001; Geeraerts, 1997); (ii) a cross-linguistic and anthropological perspective (Levinson, 2003; Pederson, 1998); (iii) a developmental perspective (Tomasello, 2003). However, until recently, intralingual and sociolinguistic diversity has been largely ignored. This is also true of research on conceptual metaphor where introspective research has been done from a monolingual perspective (e.g. Feldman, 2006; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980, 1999) and a cross-linguistic perspective (e.g. Kövecses, 2005, 2006). However, now there is increasingly more research that uses statistical and corpus-based strategies. Monolingual corpus studies on metaphor include Koller et al. (2008), Sardinha (2008), and Semino (2006), whereas examples of cross-linguistic studies are Charteris-Black & Musolff (2003) and Chun (2002). Nevertheless, none of this research addresses language-internal variation. In Terminology, there is a growing number of corpus-based studies that provide statistical data on conceptual and linguistic metaphor in architecture (Caballero, 2006), civil engineering (Boquera, 2005), and marine biology (Ureña & Faber, 2011). In fact, in the same way as in Cognitive Linguistics, Terminology has also experienced a Metaphor and denominative variation in science 3 sociocognitive shift, which brings communication-oriented and discourse-centered research to the forefront (Temmerman & Kerremans, 2003). For instance, Ureña & Tercedor (2011) establish a typology of sociocognitive patterns for marine biology metaphor and highlight how they reflect interlinguistic differences and similarities. Such research complements and enriches monolingual work on the sensorimotor underpinnings of terminological metaphor (e.g. Ureña & Faber, 2010). It is only recently that language-internal variation has started to be addressed in depth in domain-specific and specialized language. One of the sociolectometric studies that address the convergence and divergence between intralingual varieties in domainspecific discourse is Da Silva (2010) for Brazilian and European Portuguese in football and clothing. There are studies on terminological diversity in different specialized knowledge domains, such as energy fields (Dury & Lerva, 2008) and American Legal English (Goźdź-Roszkowski, 2011). To further research in terminological variation, this study examines a corpus of marine biology texts in Peninsular Spanish (PS) and Latin American Spanish (LAS). The results explain why these varieties of Spanish have different designations for the same sea organism. The focus is thus on types of formal onomasiological variation (Geeraerts, Grondelaers & Bakema, 1994) (i.e. intra-lingual denominative diversity) and its pervasiveness in Spanish scientific discourse. Also addressed is the incidence of metaphor in specialized concept formation and designation. The difference between synonymy and variation has always been a controversial topic. According to the standard view, synonymy concerns lexical change whereas variation involves syntactic or morphosyntactic order change, morphological change, as well as orthographic and typological change (Freixa, 2002). Nevertheless, Suárez (2004, Metaphor and denominative variation in science 4 p. 65) claims that there are currently no conclusive criteria that differentiate variation from synonymy. For this reason, variant and synonym are used interchangeably in this paper. All types of variant retrieved from the corpus were considered and computed, except for orthographic and typological change (e.g. seafan, sea fan, sea-fan). Our vision of synonymy is closely linked to context. According to Hamon and Nazarenko (2001, p. 200), two terms X and Y are synonymous in a context C if both terms are syntactically identical and semantically substitutable in that context. This assumption is central to our analysis because as reflected in our corpus data, the meaning of single-word terminological variants can vary or even be deactivated when the term is decontextualized. The application of domain-specific strategies previously used for semi-automatic metaphorical term retrieval (cf. Ureña & Faber, 2011) provided qualitative and quantitative evidence of regularities in language-internal terminological variation. In this sense, our study explains the causes of specialized language variation with a particular emphasis on metaphor. This paper also shows how both variation and metaphor operate to channel conceptualization and knowledge transfer in scientific communication. The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the materials and method used in the study to find terminological variants, identify their metaphorical nature, and quantify them. Section 3 explains how the research method was applied and discusses the qualitative (3.1) as well as the quantitative results (3.2) obtained. Finally, Section 4 summarizes the conclusions that can be derived from this research. 2. Materials and method Metaphor and denominative variation in science 5 2.1 Research objectives Our research study had the following objectives: To obtain the onomasiological range of a set of concepts referring to sea organisms, namely the nearly total set of expressions that occur as designations of each of these concepts in a text corpus (Geeraerts & Speelman, 2010). To quantify the incidence of the types of intra-linguistic term variation in the corpus. In this regard, particular attention was paid to geographical variation, interlinguistic borrowings, and cognitive perspective. To quantitatively determine the significance of metaphor as a trigger of terminological heterogeneity. To achieve these goals, a corpus of marine biology texts was processed and analyzed. Details about this corpus are provided in section 2.2. 2.2 The corpus The search for observational patterns inevitably involves examining authentic corpus data, regardless of the theoretical model chosen. This type of bottom-up methodology is the foundation of usage-based linguistics (Langacker, 1999, 91). The analysis of authentic data is even more important in metaphor research because corpus evidence helps users to detect cases of inactive conventional metaphors and compensates for the arbitrariness of dictionaries (Charteris-Black, 2004, p. 19). Accordingly, we compiled a corpus of texts from Spanish academic journals on marine biology and environmental science. Some of the journals are included in the Journal Citation Reports2, which provides an objective means to rank the world’s leading journals with quantifiable, statistical information based on citation data. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 6 Although the other journals in the corpus did not have a JCR ranking, they were considered to be quality publications because they were published by official organisms or because they appeared either on the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) or the Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal (Redalyc) websites. These websites have a strict set of norms, guidelines, and selection criteria that guarantee the quality of the articles3. Geographical parameters are a major cause of intralingual lexical variation (Geeraerts et al., 2010). In this study, geographical distance was a particularly productive cause of intra-lingual terminological diversity. For this reason, the journals were grouped according to the country or region whose sea life is described. In this sense, not only were Peninsular Spanish (PS) and Latin American Spanish (LAS) compared, but also the varieties of each that were spoken in a country or region. Table 1 lists the journals in this study. Table 1. Spanish academic journals and the number of research articles and tokens in the corpus Mexico JCR Citation Index 0.041 Number of articles 11 Chile 0.032 57 450,335 Spain 0.028 64 609,998 Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas Spain — 1 (book) 152,208 Investigaciones Marinas Chile — 56 449,506 Costa Rica — 33 252,069 Colombia — 28 276,371 Journal Origin Ciencias Marinas Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía Instituto Español de Oceanografía Revista de Biología Tropical Boletín de Investigaciones Marinas y Costeras Tokens 74,792 Metaphor and denominative variation in science Multequina – Latin American Journal of Natural resources Argentina — 6 44,584 Total: 256 Total: 2,309,863 7 2.3 Lects and causes of variation in this study To quantify intralingual variation in marine biology, it was first necessary to gain knowledge about the different causes of this variation. Table 2 shows Freixa’s (2006, p. 69) typology, which helped us to carry out our study. The left column lists six types of variation and the right column, two or three subtypes for each. Paying attention to this classification enabled us to subsequently focus on those causes that were expected to have a significant impact on the marine biology terminology (see below). Table 2. Causes of terminological variation Type Subtype 1. Preliminary causes Linguistic redundancy Arbitrariness of the linguistic sign 2. Dialectal causes Geographical variation Chronological variation Social variation 3. Functional causes Adaptation to the level of language Adaptation to the level of specialization 4. Discursive causes Avoiding repetition Linguistic economy 5. Interlinguistic causes Cohabitation of the “local” term and the loanword Diversity of alternative approaches 6. Cognitive causes Conceptual imprecision Ideological detachment Differences in conceptualization Based on corpus data, we estimated the importance of these causes and evaluated their overlap. A language-internal variant is also known as a lect, a general term used to Metaphor and denominative variation in science 8 refer to a wide range of language varieties, such as dialects, regiolects, national varieties, registers, styles, and idiolects (Geeraerts, 2006, p. 30). Our aim was to explore how lectal variables in marine biology texts pattern with each other as well as with linguistic variables (Geeraerts, 2010b, p.6). As previously mentioned, not all of the subtypes in Table 2 were considered in the corpus. In this regard, we only focused on terminological hetero-variation (when different experts name the same concept in different ways) and excluded self-variation (when an expert uses different designations for the same concept) (Freixa, 2006, p. 52). Self-variation normally occurs for discursive and stylistic reasons (e.g. avoidance of repetition). In contrast, hetero-variation typically emerges from geographical, cognitive, and interlinguistic factors (Freixa, 2005), which are more relevant to denotational synonymy in scientific discourse. This study thus explores the characteristics and relational structure of concepts (cognitive causes) in which metaphor plays a leading role. Accordingly, it analyzes conceptualization and its relation to the sociocommunicative factors that have an impact on term choice (geographical and interlinguistic causes). This study complements previous research by providing quantitative empirical evidence of the most recurrent types of denominative terminological hetero-variation in specialized language. This is all-important because currently there are no reliable data on the importance of any of these causes. 2.4 Method We applied a set of corpus-searching techniques devised in a previous study (Ureña & Faber, 2011) to retrieve English-Spanish metaphor term pairs. These techniques were the following: (i) extraction with target domain keywords; (ii) extraction with source Metaphor and denominative variation in science 9 domain keywords; (iii) extraction with lexical markers. This third technique was found to be particularly useful for the semi-automatic extraction of language-internal synonyms. Lexical variation has rarely been studied as a sociolinguistic variable because there is the problem of determining whether two words are semantically equivalent and whether they designate the same concept (Geeraerts, 2010a). The lexical markers provide a solution for this problem. Furthermore, a tagging system was used to quantify the occurrences of synonyms. This quantification also involved measuring and parameterizing terminological divergence in PS and LAS as well as between more local varieties within the continent. One of the very few sociolectometric studies that address the convergence and divergence between intralingual varieties in specialized discourse is Da Silva (2010) for Brazilian and European Portuguese. Unlike our study, Da Silva addresses domainspecific rather than specialized terminology, and does not specify which strategies were used to retrieve variants from his corpus. Moreover, his study is diachronic, whereas ours is synchronic. Finally, it was necessary to identify the metaphorical basis of the terminological variants drawn from the corpus. Metaphor identification is often understated in current research, and this applies to specialized language as well (Caballero, 2006, p. 65). This can lead to somewhat unreliable results since metaphor identification is far from easy. From a linguistic perspective, studies of terminological metaphor are mostly based on intuition and random inference to determine the metaphorical nature of terms. However, there are strategies that can be used to avoid subjective choices. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 10 We used two strategies to obtain objective evidence of metaphorical usage. The first strategy involves exploring the linguistic context of the term in academic article(s) and online marine biology databases, such as Fishbase (http://www.fishbase.org), in search of an explicit or implicit explanation. Context analysis was performed by using the View Text option in the Concord module of Wordsmith Tools. This function displays a cotext of 400 words for single concordance lines, as shown in context (1). This context, which was extracted from an academic journal published in Cuba, contains an explicit explanation of the figurative meaning of pez león [lionfish]. As specified in (1), this fish “belongs to the family Scorpenidae, which means little scorpion in Greek due to the pointed protuberances that inject potent venom”. (1) El pez león (Pterois volitans) […] pertenece a la familia de los Escorpénidos o peces espinosos, del griego skorpaina (diminutivo de escorpión), por sus prolongaciones espinosas y la potencialidad de su veneno. (Revista Cubana de Medicina Militar 42(2), 235-243) Context (2), which was extracted from an academic journal published in Venezuela, explains that “scorpion fish have strong, short, erectile spines with anterolateral poisonous glands showing elongates cavities”. (2) Los peces escorpión del género Scorpaena […] poseen espinas o púas eréctiles cortas y fuertes (12-13 en su aleta dorsal, 2 en la pélvica y 3 en la anal), las cuales tienen en su porción antero-lateral glándulas de veneno con cavidades alargadas. (Investigación Clínica 49(3), 299-307). This is thus an explicit explanation of the same metaphorical basis of pez león. In this case, however, the term defined is pez escorpión [scorpionfish], which designates a fish of the same family as pez león. These examples anticipate more cases of terminological variation found in this study. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 11 Context (3) provides an implicit explanation of why pez mantequilla [butter fish] receives its name. It is argued that “a rectal excretion of a greasy substance after consumption of certain fish with high fat content” is analyzed, concretely, “after intake of butterfish”. The metaphorical nature of pez mantequilla can thus be inferred from this description. (3) Se conoce como keriorrhea la emisión rectal de una sustancia grasa anaranjada tras el consumo de ciertos peces con alto contenido en grasas. Se presenta el caso de dos niños que manifestaron este cuadro tras consumir un pescado llamado "pez mantequilla". (Revista de Pediatría y Atención Primaria 14(3), 49-52). When the contextual analysis was not sufficient to attest the metaphorical motivation of a term, it was necessary to examine the image of sea organisms in the electronic database consulted as well as on the Google image search engine. This study includes pictures of sea organisms, some of which were crucial to finding the metaphorical motivation of their terms (e.g. Picture 7). By applying these two strategies, we were able to test the metaphorical nature of marine biology terms against empirical data. 3. Results and discussion This section explains how lexical markers and tags facilitated the retrieval of intralingual terminological variants in Spanish. 3.1 Qualitative study As previously mentioned, lexical markers were used to retrieve terminological variants. These markers, which recovered literal and figurative common names from the corpus, were both domain-specific and standard. The domain-specific markers were taxonomic Metaphor and denominative variation in science 12 designations4 and the standard markers were the phrases (localmente) conocido/a como “(locally) known as”, denominado/a (comúnmente) como “(commonly) named”, and (también) llamado “(also) called”. Both types were concordanced with the lexical analysis program Wordsmith Tools®. The collocational horizons of the search word were five words to the left and five words to the right of the node. 3.1.1 Domain-specific markers As evidenced in the concordances and collocates, taxonomic designations were extremely productive lexical markers for common-name terms. This was crucial for the identification of metaphorical PS-LAS variants because no theory of metaphor can predict which word forms will be used more often metaphorically (Sardinha, 2008, p. 128). Taxonomic designations were collected from the co-texts of extracted terms and from the checklists in the academic articles (see Figure 1 for a species list from a Mexican estuary). Although taxonomic designations are used to guarantee referential accuracy, the corpus data showed that synonymy is frequent in specialized discourse. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 13 Figure 1. Checklist of fish species in the Tuxpan-Tampamachoco estuary, Mexico. The concordance lines showed significant convergence in the way the two speech communities designate the same concepts. However, the concordances also reflected many denominative differences. This can be observed in concordance lines (4) and (5), which include the pair yubarta and ballena jorobada, both of which are Spanish terms for humpback whale. Although the quantitative analysis revealed that both terms are commonly used by experts in Spain and Latin America, it was also evident that PS biologists tend to favor yubarta (81 hits across a range of articles) over ballena jorobada (35 hits). In contrast, LA biologists clearly prefer ballena jorobada (97 hits) to yubarta (1 hit). The comparison of each term in the onomasiological range of a concept in the marine biology corpus is one of the three criteria that were used as evidence of terminological Metaphor and denominative variation in science 14 variation mediated by geographic fragmentation. The other two criteria were the following: (i) the lexical markers (localmente) conocido/a como “(locally) known as”, and (también) llamado x en y “(also) called x in y” (where x stands for the commonname term and y stands for the place where the term is used); (ii) the first author’s knowledge of scientific terminology. In the previously mentioned case, it was the taxonomic designation Megaptera novaeangliae that helped to identify the variants yubarta and ballena jorobada in examples (4) and (5). (4) Este último es el caso de la YUBARTA (Megaptera novaeangliae) que, aun siendo habitual en los océanos de todo el mundo (Fernández-Casado et al. 2001), en raras ocasiones se adentra en el interior del MAR MEDITERRÁNEO (Aguilar 1989) (IEO < Galemys 18(1-2), 2006, Notas, 40-42) (5) La BALLENA JOROBADA del Pacífico suroriental (Megaptera novaeangliae) migra entre el área de reproducción, principalmente en las aguas de ECUADOR Y COLOMBIA, y el área de alimentación alrededor de la península Antártica. (Rev. Biol. Mar. Ocean.41(1), 2006, 11-19) The metaphorical motivation of these terms indicates that this is a terminological doublet, i.e. a term pair in which the semantics of one term is transparent whereas the other is Latin in origin, and thus, opaque (Suárez, 2004, p. 64). Accordingly, yubarta comes from the French jubartes, which in turn stems from gibbus (Latin for Spanish giba/joroba, ‘humpback’). Ballena jorobada, ‘humpback whale’, is a transparent metaphor. In both cases, a physical feature is compared with the curve of the whale’s back when diving. However, despite its opaque meaning, the formal term, yubarta, is more frequent in PS scientific discourse. Visuals greatly assist experts in explaining specialized concepts (Fernandes, 2004). This is true for concept names based on resemblance5 metaphor concepts (see Picture Metaphor and denominative variation in science 15 1), which illustrates the motivation for the metaphorical transfer of the synonyms yubarta and ballena jorobada. Picture 1. Humpback of the ballena jorobada/yubarta. The terms in contexts (4) and (5) are examples of how geographic fragmentation prompts intralingual variation, even when the cognitive perspective regarding the motivation for the naming of the concept (i.e. metaphorical transfer) is shared by the two speech communities. Other examples in this study show that geographic fragmentation and cognitive preferences generally go hand in hand since different cognitive perspectives often involve different speech communities, which are separated geographically. The concordances also show the influence of English on Spanish, which triggers term variation in Spain and Latin America. This influence was reflected in the corpus by interlinguistic borrowings, adaptations of the English terms, and literal translations. These three types of borrowing are what Bertaccini, Massari & Castagnoli (2010, p. 16) call pathological synonymy. Unlike physiological synonymy, pathological synonymy is arbitrary (i.e. not functional), involves the coexistence of a foreign and a native term, and gives rise to a wide range of equivalent expressions. An example of term adaptation is the LAS term macarela in (6), which stems from mackerel. As shown in (7), this adaptation is an example of intra-lingual variation Metaphor and denominative variation in science 16 because the PS designation of this fish (Scomber scombrus) is caballa, the Latin word for Spanish yegua and English mare. This is a metaphor originally based on the jumping and flying ability of the fish Cheilopogon heterurus (Exocoetidae family), whose morphology and striped dorsal skin partially resemble that of the Scomber scombrus (Pictures 2 and 3). This physical resemblance caused the Scomber scombrus to also be known as caballa (Coromines & Pascual, 1997). (6) La abundancia relativa de la MACARELA (Scomber scombrus) fue significativamente mayor en la REGIÓN DE LA ISLA PATOS, respecto a cualquier otra región. (Revista de Biología Tropical, 56(2), 2008, 575-590) (7) La pretensión de esta tesis es tener un conocimiento más amplio de las características biológicas de la CABALLA Scomber scombrus L., 1758 del Atlántico nordeste en el norte y noroeste de la PENÍNSULA IBÉRICA. (IEO, PhD dissertation) Picture 2. Exocoetidae fish (flying fish) Picture 3. Scomber scombrus (caballa) A case of direct borrowing that causes PS-LAS variation is turbot, which was extracted by concordancing the taxonomic designation Psetta maxima. As shown in (8) and (9), LAS biologists use the terms rodaballo and turbot with a preference for the latter. In contrast, PS experts prefer rodaballo. Turbot and rodaballo occurred 51 and 10 times in the LAS texts, respectively, whereas the PS texts yielded 73 occurrences of rodaballo with no hits for turbot. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 17 (8) La alimentación de juveniles de Paralichthys adspersus ha sido provista tradicionalmente por dietas formuladas para juveniles de RODABALLO o TURBOT (Psetta maxima Linnaeus, 1758), bajo el supuesto que los peces planos tienen hábitos de vida similares (Alvial and Manríquez 1999). (Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. (1), 2011, 9-16) (9) Trataremos en particular los problemas patológicos de especies conocidas de peces planos en cultivo, como el RODABALLO (Scophthalmus/Psetta maxima), lenguado (Solea sp.), fletán (Hippoglossus hipoglossus), así como de otras especies. (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2000) Interestingly, (9) shows that denominative variation is not only present in scientific common names but also in taxonomic designations (Scophthalmus/Psetta maxima). Concordances of Tursiops truncatus, a type of dolphin, reflected that terminological diversity in Spanish can be caused by literal translations from English. Figure 2 was extracted from an article in Ciencias Marinas, a bilingual Latin American journal. This format was extremely helpful in identifying not only literal translations, but also other types of borrowing. Figure 2 shows that LA Spanish is more influenced by English than peninsular Spanish. LA biologists use the metaphorical term delfín nariz de botella, which is the literal translation of bottlenose dolphin. This name refers to the dolphin’s snout, which is short and stubby in comparison with that of the rest of members of the Delphinidae family (see Picture 4). Figure 2. Extract from a bilingual article in Ciencias Marinas (36 (1), 2010, 71-81). Metaphor and denominative variation in science 18 In contrast, the corpus data reflected that peninsular Spanish has less of a tendency to adapt or incorporate English names. Context (10) shows that PS biologists metaphorically refer to Tursiops truncatus as delfín mular ‘mule dolphin’. The dolphin is compared to a mule because of its robust appearance as well as its energetic and hardy nature. In fact, this species is the most common in aquaria, where it is in close and constant contact with people. (10) […] las aguas que rodean el ESTRECHO DE GIBRALTAR, del 8 al 26 de julio de 1993, se realizaron períodos de observación para el avistamiento de cetáceos. Se hicieron 62 avistamientos que correspondieron a las siguientes especies: delfín común Delphinus delphis Linnaeus, 1758 (31 % de los avistamientos); calderón Globicephala sp. (26 %); delfín listado Stenella coeruleoalba (Meyen, 1833) (23 %); DELFÍN MULAR Tursiops truncatus (Montagu, 1821) (18 %) (IEO, 24, 1997, 65-73) The corpus revealed that LA scientists also make use of the alternative term tursión (11), an adaptation of the Latin tursio ‘porpoise’ and the Greek ops ‘face’, which combine to form Tursiops. Curiously enough, truncatus, the second constituent, also refers to the shortness of this animal’s snout in that it appears to be cut off or truncated. (11) El primero corresponde a un grupo observado junto con TURSIONES (Tursiops truncatus) y calderones de aleta corta (Globicephala macrorhynchus) en bahía Cumberland, isla Robinson Crusoe frente a CHILE CENTRAL. (Rev. Biología Marina y Oceanografía, 38(2), 2003, 81-85). Metaphor and denominative variation in science 19 Picture 4. Short snout of the bottle-nose dolphin. These corpus examples provide evidence that Tursiops truncatus has three metaphorical common names. In this case, variation is largely due to the influence of the English language on LAS. Different cognitive perspectives are associated with the geographical distance separating LAS and PS. 3.1.2 Standard markers Standard markers were very productive in identifying synonyms on an intracontinental scale. For instance, the phrase también llamado ‘also called’ in (12) revealed the presence of the terms flecha de plata and matungo, together with pejerrey. All three terms designate a fish typically found in Argentina and Uruguay. (12) Unos años más tarde, en 1960, se transplanta oficialmente en nuestro medio acuático una especie más, el PEJERREY (Odontesthes bonariensis) o también llamado vulgarmente «FLECHA DE PLATA» o «MATUNGO», oriundo del RÍO DE LA PLATA, RÍO PARANÁ y URUGUAY MEDIO E INFERIOR y LAGUNAS DE LA CUENCA DEL RÍO SALADO (BUENOS AIRES) (Ringuelet, 1967). (Multequina 4, 1995) Although the three are LAS variants, pejerrey is a generic term, widely used across Latin America. This supports the claim that lectal varieties are not necessarily discrete entities with well-defined characteristics and strict isoglosses (Kristiansen, 2008, p. 59). However, terminological diversity is a fact since flecha de plata and matungo are mostly used in Argentina and Uruguay. In fact, the geographical range (Geeraerts & Speelman, 2010, p. 32) of matungo is specified in its non-figurative general language sense in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española: ARG. y UR. Dicho de un caballo: Que carece de buenas cualidades físicas. ‘ARGENTINA and URUGUAY. Of or relating to a horse in poor physical condition’ Metaphor and denominative variation in science 20 More specifically, matungo is a Latin American word with an African origin. This is a common linguistic phenomenon in the Latin America because of the importation of African black slaves that began in the 15th century (Lapesa, 1942, p. 534). Matungo thus reflects that borrowings from indigenous languages even exist in scientific terminology. These borrowings may in turn be the cause of intralinguistic variation affecting the geographical continuum of a speech community, as is the case of matungo with respect to flecha de plata (typically Argentinean and Uruguayan) and pejerrey (a more widespread term). According to Geeraerts & Speelman (2010, p. 23), lexical variation in a geographical or social continuum occurs because societal and material factors trigger the interaction of different language systems. In studies on metaphor, the significance of borrowing has been discussed in a range of knowledge fields. For instance, Trim (2011, p. 84), who conducts a diachronic analysis of the evolution of conceptual mapping, argues that a great deal of borrowing takes place in drug terminology as a result of its international nature. However, research in metaphorical borrowing in marine biology is yet to be exploited. In our case, the phrase que carece de buenas cualidades físicas ‘in poor physical condition’ in the definition of matungo is a cue for the metaphorical motivation of the term since it establishes a comparison between an enfeebled horse and a fish with a thin elongated shape (Picture 5). The metaphorical motivation of pejerrey is also grounded in the shape and physical appearance of the fish. However, rather surprisingly, the cognitive perspective in this case is positive instead of negative. The explanation lies in the term itself, which reflects the fact that specialized language is subject to the same rules as general language. More specifically, pejerrey is combination of pej6 (phonological adaptation of pez ‘fish’ and Metaphor and denominative variation in science 21 rrey (orthographic adaptation of rey ‘king’). Consequently, the term, pejerrey “king fish”, foregrounds the slimness and elegance of this fish. In fact, its elongated shape and shiny gray color is also the metaphorical motivation of the term flecha de plata ‘silver arrow’. Therefore, the same fish can be named from a negative, positive, and neutral cognitive perspective. Unlike the term pair, ballena jorobada-yubarta, the onomasiological range of Odontesthes bonariensis reflects different cognitive perspectives, underlying the geographic fragmentation of the designations. Picture 5. Fish known as pejerrey, flecha de plata, or matungo. When pejerrey was concordanced, the data showed that this term designated a different fish in peninsular Spanish, as shown in context (13). (13) Aspectos de la biología reproductora del PEJERREY o GUELDE BLANCO Atherina presbyter Cuvier, 1829 (Atherinidae) en GRAN CANARIA (Islas Canarias) […] En Canarias, esta especie, denominada comúnmente GUELDE BLANCO, es utilizada como cebo vivo en la pesquería de túnidos desarrollada por la flota artesanal. (Boletín Instituto Español Oceanografía 17(3-4), 2001) This example supports our claim that the meaning of a single-word term can change, depending on the context. Accordingly, pejerrey can refer to different fish species (Atherinopsidae or Atherinidae), if it appears in a PS article or in an LAS article. However, not surprisingly, the same metaphor has been lexicalized in both speech communities because the two fish families belong to the same order. Atheriniformes Metaphor and denominative variation in science 22 have an elongated and slender shape, and furthermore, the Atherina presbyter is grayish in color (see Picture 6). Picture 6. Atherina presbyter. Interestingly enough, the standard marker denominada comúnmente ‘commonly known as’, together with the more specific geographical marker en Canarias ‘in the Canary Islands’, showed that the generic PS term pejerrey has a lectal variant, guelde blanco ‘white guelde’. Consequently, geographic fragmentation also affects PS texts. The geographical origin of the term was confirmed by the entry for guelde in the Diccionario Básico de Canarismos (2010, p. 227): (Atherina presbyter) Pequeño pez pelágico de color plateado […] Los pescadores lo suelen utilizar como carnada […] En algunas zonas de Canarias se conoce con los nombres de “longorón” y “ruama”. ‘(Atherina presbyter) Small pelagic, silvery fish […] Fishermen generally use it as bait […] In certain areas of the Canary Islands, this fish is known as longorón and ruama’. This dictionary entry is relevant for three reasons. First of all, this entry contributes two more lectal variants for Atherina presbyter, i.e. longorón and ruama. Secondly, the Canary Islands term, ruama, is a variant of ruana, which means grayish in color (Diccionario de la Real Academia Española). The terms guelde blanco ‘white guelde’ and ruama are thus examples of social categorization (Kristiansen, 2008, p. 417), which is a cognitive process involving the accentuation of intragroup similarities and Metaphor and denominative variation in science 23 intergroup differences on a continuous dimension. In this sense, white and gray are colors that overlap in a transition zone of the dimension of color. The color of Atherina presbyter (light gray or grayish white) lies in this transition zone (see Picture 6). One group of Canary Islanders originally perceived the color of this fish as light gray (ruama), whereas another group perceived the color as dirty white (guelde blanco). Thirdly, the dictionary entry states that fishermen use this fish as bait. The term guelde evidently resembles gueldo, which is defined by the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española as follows: Cebo que emplean los pescadores, hecho de camarones y otros crustáceos pequeños. ‘Bait used by fishermen, which consists of shrimp and other small crustaceans’ The term guelde must thus be an insular lectal variant of the general language word gueldo, which designates not only small crustaceans, but also fish. These examples not only show that geographical fragmentation in specialized language occurs in PS and LAS, but also within Spain. The corpus also yielded instances of country-specific LAS variation in which metaphorical thought figures prominently. For example, the keywords conocida como ‘known as’ in (14) show that the species Fissurella crassa is called lapa de sol ‘sun limpet’ in northern Chile, whereas it is called lapa ocho ‘eight limpet’ in central and southern Chile. This means that the maximal geographical range (Geeraerts & Speelman, 2010, p. 32) of the term lapa ocho is wider than that of lapa de sol. (14) Con este propósito se ha escogido a Fissurella crassa, conocida como “LAPA DE SOL” SUR en el NORTE DE CHILE (Bretos 1978) o “LAPA OCHO” en la ZONA CENTRAL Y del país. (Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía, 33(2), 1998: 223–239) Metaphor and denominative variation in science 24 Again, metaphor is a cognitive cause underlying geographical fragmentation in intralingual diversity. Lapa ocho refers to a limpet whose shape is more ellipsoid than normal, and which resembles the number eight (Picture 7). In contrast, lapa de sol is not metaphorical, and refers to the fact that this limpet usually clings to rock clefts where it is easily reached by the sunlight. Picture 7. Lapa ocho [eight limpet]. The physical and behavioral characteristics of marine organisms have been shown to have a crucial bearing on their conceptualization and lexicalization. In fact, certain concept features enhance onomasiological heterogeneity not only in everyday language (Geeraerts & Speelman, 2010, p. 24), but also in specialized language. By the same token, the different cognitive perspectives adopted to conceptualize marine biology entities through metaphor demonstrate that “experience affects representation” (Bybee, 2001, p. 67). In other words, these perspectives are an integral part of the dynamics of cognition in specialized language, according to which “cognition is a dynamic process in which concepts and conceptual structures adapt to the speakers’ cultural, social and situational environment” (Fernández-Silva, Freixa & Cabré, 2001). 3.2. Quantitative study: Corpus annotation and term quantification Metaphor and denominative variation in science 25 The second tool used was a manual tagging system. Corpus annotation has been shown to yield optimal results concerning different aspects of metaphor description. Manual tagging is the most frequent type of corpus formatting. For instance, Semino (2006) annotates her corpus to describe a specific kind of metaphorical speech act annotation, whereas Sardinha (2008) annotates his corpus to compute the probabilities of each candidate word form being a vehicle metaphor. Another body of research relies on artificial intelligence, which offers automatic semantic field annotation tools, such as the UCREL Semantic Annotation System for English texts (Koller, Hardie, Rayson & Semino, 2008; Hardie, Koller, Rayson & Semino, 2007), and metaphor extraction systems that exploit the codification of pre-defined semantic relations between units in lexical databases, as is the case of CorMet (Mason, 2004). Although convincing results have been obtained, the approaches of these studies are not suitable for our research. First of all, it is not clear how the USAS could be systematically exploited to reflect intra-lingual differences of resemblance metaphors in Spanish, something that is guaranteed by our tag set. Secondly, the procedure used in projects such as CorMet is only valid for verbs7, whereas this study focuses on nouns. All instances of intra-lingual variants in the PS and LAS corpora were annotated with one of the tags used in Ureña & Faber (2011). Accordingly, TAXO was placed next to each taxonomic designation co-occurring with a figurative or literal common name term. Concordancing this tag with Wordsmith Tools was particularly useful since it also facilitated the retrieval of those PS and LAS terms that were not metaphorical in nature. The next step was to analyze the TAXO-tagged terms and their co-text to identify cases of language-internal synonymy. Needless to say, non-specific markers, such as conocido como ‘known as’, were also of great help for this purpose. The goal was not Metaphor and denominative variation in science 26 only to quantify PS and LAS terminological synonyms, but also to classify them based on geographic fragmentation and interlinguistic borrowings8. For this purpose, the following tags were added to the variants identified: - Tags indicating geographic fragmentation: o INTER: for terms reflecting PS-LAS variation o LAT: for terms reflecting varation in LA countries or regions o PEN: for terms reflecting variation on the Iberian Peninsula and Islands - Tags indicating English-Spanish interlinguistic borrowings: o DB: direct borrowing o ADA: adaptation o LT: literal translation In addition, the tag METAPH was crucial for the computation of Spanish-language metaphorical variants. Figure 3 is a Wordsmith Tools screenshot of some of the concordances from the corpus by concordancing the tag INTER. This procedure facilitated the retreival of LASPS terminological synonyms. The cotext of many of the terms reveals that they are used in Latin America or Spain. Figure 3. Concordances of the INTER tag with PS-LAS term variants. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 27 In Figure 3, concordances 1 and 2 include the synonyms tortuga golfina ‘gulf turtle’ and tortuga olivácea ‘olive turtle’, mostly found in PS texts, and their variant tortuga lora ‘parrot turtle’, only found in LAS texts. Concordances 3 and 4 (Fig. 3) show the LAS term tortuga cabezona ‘big-head turtle’ and tortuga boba ‘loggerhead turtle’, widely used in the PS texts. Concordances 5 and 6 (Fig. 3) include the PS term lampuga [no translation] and its LAS synonym pez dorado ‘golden fish’. Concordances 7 and 8 (Fig. 3) show the term ostión del Pacífico ‘giant oyster from the Pacific’, used in peninsular Spanish, and the LAS variant ostra rizada ‘curly oyster’. As can be seen, many of these terms are metaphorical in nature. Figure 4 shows concordances of the tag LAT, which contain terminological variants in Latin America. Concordances 1 and 2 (Fig. 4) retrieve the term pargo manchado ‘stained snapper’, used in Costa Rica, and pargo lunarejo ‘spotty snapper’, which appears in a Mexican article. Concordances 3 and 4 (Fig. 4) include the Mexican, Colombian and Ecuadorian synonyms, pata de mula ‘mule-leg (clam)’, piangua [no translation], and concha prieta ‘swarthy shell’, respectively. These synonyms were also retrieved by concordancing the lexical marker conocido como ‘known as’. Concordances 5 and 6 (Fig. 4) contain the two common name variants of Nodipecten subnodosus in the corpus, escalopa (no translation) and almeja mano de león ‘lion’s paw clam’. Figure 4. Concordances with terminological synonyms in Latin America. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 28 Figure 5 includes concordances obtained with the tag PEN, which was used to retrieve PS synonyms. Again, the cotext indicates the origin of the terms. Concordances 1 and 2 (Fig. 5) show the Canary Islands metaphorical synonyms sebadales ‘barley field’ and manchones ‘soiled field’, which are variants of the standard Spanish term pradera marina ‘marine meadow’. Concordance 3 (Fig. 5) contains chanquete ‘transparent goby’, used in Murcia to designate the species Aphia minuta. Concordance 4 (Fig. 5) shows that the standard term besugo americano ‘American sea bream’ is called alfonsiño ‘dear/little alphonse’ and fula de altura ‘deep-sea fula’ on the Canary Islands. Fula is a term used in Canary Islands to designate the bell-shaped umbrella of a jellyfish (Alvar, 1975, p. 432). In Concordances 5 and 6 (Fig. 5), the standard term boquerón ‘whitebait’ is called anchoa ‘anchovy’ in the north of Spain, including the Cantabrian region. In concordances 7–8 (Fig. 5), the standard term pargo ‘snapper’ is called bocinegro ‘black snout’ in the Canary Islands. Figure 5. Concordances including terminological variants in Spain. Figure 6 includes concordances of the tags, LAT DB and INTER DB, showing instances of direct borrowings from English. Only a few examples reflected PS-LAS or LA terminological divergence. Concordance 1 (Fig. 6) shows an example of direct borrowing, halibut, extracted from an LAS article. As can be observed in the taxonomic Metaphor and denominative variation in science 29 designation in concordance 2 (Fig. 6), this borrowing is synonymous with the metaphorical term lenguado del Atlántico ‘tongue-shaped (fish) from the Atlantic’. Since this term appeared in both LAS and PS publications, the tag LAT/INTER was inserted. Concordance 3 (Fig. 6) includes the metonymic direct borrowing redclaw, which is synonymous with the standard term langosta australiana de agua dulce ‘Australian freshwater lobster’ in concordances 3 and 4 (Fig. 6). Concordances 5 and 6 (Fig. 6) contain the metaphorical PS term pez reloj ‘clock fish’ and its LAS synonym, orange roughy, a direct borrowing from the English language. Figure 6. Concordances with examples of direct borrowings and their synonyms. Figures 7 and 8 show concordances of the tags LAT LT and INTER LT, which contain terminological synonyms that are literal translations of the English terms. They were obviously literal translations because most were extracted from English-Spanish articles in the bilingual journal Ciencias Marinas. In other cases, the original English terms were found in English-language articles in JCR academic journals, such as Marine Biology and Environmental Biology of Fishes. Concordances 1 and 2 (Fig. 7) include two LAS metaphorical variants of the seal species Otaria flavescens: lobo marino ‘sea wolf’ and león marino ‘sea lion’. Lobo marino is the standard name in LAS and PS. As for león marino, it is hardly a coincidence that the English common name for this species is sea lion, as shown in (15). Metaphor and denominative variation in science 30 Figure 7. Terminological variation in Latin America caused by the influence of English. (15) Several major breeding areas have been defined for the South American SEA LION (Otaria flavescens) along the Atlantic Ocean including the Uruguayan and Patagonian coasts. (Marine Biology, 158(8), 2011: 1857-1867) Figure 8 includes PS-LAS terminological variants. Concordance 1 (Fig. 8) contains tiburón limón, which appeared in many LA articles, and is a literal translation of the metaphorical English term, lemon shark (the shark is yellowish in color). Concordance 2 (Fig. 8) shows the metaphorical variant tiburón galano ‘gallant shark’ in a PS text. Concordances 3 and 4 (Fig. 8) include the PS term langostino blanco ‘white prawn’, and its LA synonym camarón rosado, which is the literal translation of pink shrimp. Finally, concordances 5-6 (Fig. 8) show the PS term rabil [a type of mill] and the LA atún aleta amarilla, which a calque of yellowfin tuna. Figure 8. PS-LAS variation due to English. Finally, two adaptations from English were found. Of these two, only macarela reflects a PS-LAS divergence. In contrast, marlín/marlines (adaptations of marlin) are used in both Spain and Latin America. Figure 9 is a concordance of the tag ADA with Metaphor and denominative variation in science 31 the term marlines. This concordance also contains two metaphorical terms used by both speech communities, pez vela ‘sailfish’ and pez espada ‘swordfish’. Figure 9. Spanish adaptation of marlin. All the corpus common names, including the previous examples, were classified and quantified based on the tags and lexical markers. The results showed that the corpus contained 15,327 metaphorical terms for sea organisms. Table 3 shows the figures obtained for (metaphorical) variants of different types. Table 3. Figures/distribution of tokens of terminological variants. 2,309,863 Tokens Variants and % Metaphorical variants and % PS-LAS variants (metaphorical) and % PS variants LAS variants (metaphorical) (metaphorical) and % and % 11,589 9,468 3,189 (2,472) 3,791 (2,273) 4,609 (4,723) 0.5% 0.4% 0.14% 0.16% 0.2% Table 3 shows the number of tokens rather than of types to provide a more accurate quantification of Spanish-language synonyms in marine biology. This methodology was applied by Geeraerts & Speelman (2010, p. 36), who prefer a token-based measure of diversity. Although the terminological variation in the corpus is fairly low, the figures still reflect the presence of synonymy in specialized language. As shown in Table 3, intra-continental and country-internal variation outnumbers intercontinental variation. A possible explanation for this is that in international communication scientists tend to use standardized terminology to avoid ambiguity. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 32 It is also evident that metaphor is a recurrent cognitive mechanism of term creation, especially in Latin American Spanish. In all likelihood, the reason for this is that LAS is more influenced by English as well as indigenous languages. In fact, the corpus revealed a good number of terms of indigenous origin (as many as 29 terminological units of this type were identified by means of the semi-automatic strategies applied in this study). However, many of them did not generate synonym pairs, probably because the organisms designated are only found in Latin America. For example, (16) contains the huachinango, which clearly stems from Quechua. Even its taxonomic designation, L. peru, indicates the origin of this species. (16) Se identificaron registros de pesca completos para 18 especies de importancia comercial pertenecientes a ocho familias (tabla 1). La especie más capturada en la Bahía de La Paz entre 1998 y 2005 fue el HUACHINANGO L. peru, con 43% de la captura total. Also found were PS terms with no correlates in the LAS texts (as many as 45 terms of this type were identified). In some cases, the reason was cultural (19 metaphorical terms were found to be culture-dependent). An example is ochavo (no translation) in (17), a metaphorical term that designates a fish typically found off the coasts of Spain, and which has a roundish shape (Picture 8). This shape prompts the comparison between the fish and an ochavo, a coin used in Spain from the reign of King Philip III until the 19th. This clearly shows that culture affects conceptualization and designation of specialized concepts through metaphor (see Ureña & Tercedor, 2011 for a finegrained classification of culture-bound metaphorical terms). It should thus not be surprising that this fish did not appear in the LAS texts. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 33 (17) EL MAR DE ALBORÁN, que está delimitado al oeste por el ESTRECHO DE GIBRALTAR y al este por la línea imaginaria que une el CABO DE GATA (ESPAÑA) con el cabo Figalo (Argelia), ocupa una superficie de unos 54 000 km2 y su fondo posee una compleja topografía con variadas subcuencas, altos estructurales y plataformas. […] En la zona costera septentrional han estado presentes, a lo largo de todo el ciclo estacional considerado (primavera, verano y otoño), las larvas de peces de diferentes grupos taxonómicos (mictófidos, espáridos, góbidos, callyonimidos, blénidos y bótidos) y de la especie Capros aper (OCHAVO). (IEO, Microfichas, 1997). Picture 8. Ochavo (Capros aper). The corpus contained 32 PS variants from the Canary Islands. The geographical distance of these Islands from the Iberian Peninsula is certainly a major cause of variation. Table 4 shows the number of variant pairs/triples produced because of geographical fragmentation and types of borrowing. Table 4. Pairs/triples of terminological synonyms and their causes. PS-LAS synonym pairs/triples PS synonym pairs/triples LAS synonym pairs/triples 65 83 111 Direct borrowing from English 9 0 3 Adaptation from English 1 0 1 Metaphor and denominative variation in science 34 Literal translation from English 16 2 21 Those pairs/triples that do not fit in any of the three borrowing types are triggered by different cognitive perspectives, which are primarily shaped by metaphorical thought. As many as 206 pairs/triples of this type were retrieved from the texts, including 13 terms stemming from indigenous languages (it should be noted that not all terms of this origin could be coupled to their corresponding equivalents since these latter were not always found in the texts). Adding up, 259 pairs/triples were identified in the corpus. 4. Conclusions Language-internal variation remains a little studied area in general language (Geeraerts et al. 2010, 6) and even more so in terminology research. To fill this gap, this paper presented the results of a corpus-based study on language variation in peninsular and Latin American Spanish in marine biology. The qualitative and quantitative results of the study show that although the percentage of terminological variation is not significant compared to the total number of tokens in the corpus, the number and types of synonyms reflect that denominative diversity is a common phenomenon in specialized language. The strategies for the semi-automatic retrieval of (metaphorical) terms focused on in this study were found to be highly productive since they effectively provided the onomasiological range of the set of sea organism concepts extracted from the corpus. The strategies also enabled us to quantify the incidence of the types of intra-linguistic term variation. The results show that geographical fragmentation, reinforced by the influence of languages other than Spanish (especially English, but also indigenous languages), is a crucial factor that triggers inter- and intracontinental variation. The Metaphor and denominative variation in science 35 figures show that in contrast to PS, LAS has a greater tendency to incorporate terms stemming directly or indirectly from the English language (25 and 2 terminological variants of this type were found in the corpus, respectively). Indigenous languages (particularly Quechua) have an influence on term coinage in LAS, which further increases terminological diversity. In fact, the results of this study provide evidence that LAS is more prone to producing terminological variants (4,609) than PS (3,791). In our opinion, it is not only the geographic closeness between North and Central/South America that prompts this phenomenon, but also the fact that in Latin America, there is more of a willingness to embrace new terms. Peninsular Spanish is more conservative in this regard though an exception is evidently the role of dialects from the Canary Islands (42 PS variants were identified). Inter-continental diversity, which is regarded as an effect of geographic fragmentation as well, is a less common phenomenon. Experts’ observation of international standardization is most likely to be a crucial factor. In any case, the number of PS-LAS variants obtained — 2,472 — is significant. The quantitative analysis also revealed the pivotal role of metaphor in prompting denominative diversity. In fact, as many as 9,468 metaphorical terms out of 11,589 variants were identified in the corpus. Again, it is LAS that is more open to metaphorical denominations than PS (4,723 and 2,273 variants, respectively). The occurrence of metaphor in LAS-PS pairs/triples is also representative (2,472 terms were extracted). It can thus be argued that conceptual salience significantly influences the occurrence of onomasiological heterogeneity in specialized communication as well. As reflected in this research, metaphoric thought is instrumental in helping experts to highlight and recall the physical and/or behavioral features that characterize sea Metaphor and denominative variation in science 36 organisms. A direct consequence of this might be that experts referred to such organisms more easily than using taxonomic designations, which are longer and opaque names. However, this is something that requires validation. Notes 1 This research was carried out within the framework of the projects RECORD (FFI2011-22397) and VARIMED (FFI2011-23120), both funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. 2 3 http://www.scimagojr.com/index.php. The SciELO website’s criteria for journal evaluation and selection can be accessed at http://www.scielo.org/php/level.php?lang=es&component=44&item=2. 4 The taxonomic designation of a species is the Latin name in binomial nomenclature used by the scientific community to classify such a species into a specific taxon. The first and the second constituents of the binomial refer to the genus and the specific name, respectively. Both constituents must be written in italics (e.g. Dicentrarchus labrax). 5 Resemblance metaphors arise from physical and/or behavioural analogy. In contrast, non-resemblance metaphors are grounded in more abstract aspects (Lakoff, 1993), although they also involve the retrieval of mental images (Ureña & Faber, 2010). 6 As the corpus showed, this phonological adaptation is widespread in the marine biology terminology, giving rise to different names, such as pejerrey and pejesapo “toad fish”. This finding supports the claim that “some systemic factors in the terminology of a domain determine the formation of new terms and the growth of terminology” (Kageura, 2002, p. 34). 7 CorMet identifies metaphors by finding systematic differences in selectional preferences between domains. A selectional preference is “a verb’s predilection for a particular type of argument in a particular role” (Mason, 2004, p. 23). 8 The third cause, cognitive perspective, was not quantified because it is comprehensive. Each of the common names included in one onomasiological range offers a distinct cognitive standpoint, which may or may not be figuratively motivated (tagged with METAPH in the corpus). Moreover, it is pointless to tag those synonyms that have the same cognitive perspective (e.g. doublet-terms). Metaphor and denominative variation in science 37 References Alvar López, M. (1975). La terminología canaria de los seres marinos. Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos, 25, 419–470. Bertaccini, F., Monica, M., & Castagnoli, S. (2010). Synonymy and variation in the domain of digital terrestrial television: Is Italian at risk? In M. Thelen, & F. Steurs (Eds.), Terminology in Everyday Life (pp. 11–20). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Bybee, J. (2001). Phonology and Language Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Boquera, M. (2005). Las metáforas en textos de ingeniería civil: Estudio contrastivo español-inglés. Doctoral dissertation, University of Valencia. Caballero, R. (2006). Reviewing Space: Figurative Language in Architects’ Assessment of Built Space. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Charteris-Black, J, & Musolff, A. (2003). ‘Battered hero’ or ‘innocent victim’? A comparative study of metaphors for euro trading in British and German financial reporting. English for Specific Purposes, 22, 153–176. Chun, L. (2002). A cognitive approach to Up/Down metaphors in English and Shang/Xia metaphors in Chinese. In B. Altenberg, & S. Granger (Eds.), Lexis in Contrast. Corpus-Based Approaches (pp. 151–174). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Coromines, J, & Pascual, J.A. (1991-1997). Diccionario crítico etimológico castellano e hispánico (6 vols). Madrid: Gredos. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 38 Da Silva, A. (2010). Measuring and parametizing lexical convergence and divergence between European and Brazilian Portuguese. In D. Geeraerts, G. Kristiansen, & Y. Peirsman (pp. 41–84). Advances in Cognitive Sociolinguistics. Berlin: Mouton de Grutyer. Dury, P., & Lervad, S. (2008). La variation synonymique dans la terminologie de l’énergie: approches synchronique et diachronique, deux études de cas. LSP and Professional Communication, 8(2), 66–79. Feldman, J. (2006). From Molecule to Metaphor: a Neural Theory of Language. Cambridge (Massachusetts): MIT Press. Fernandes, C. (2004). Interactions between words and images in lexicography: Towards new multimedia dictionaries. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Nova Lisboa, Lisboa. Fernández-Silva, S, Freixa, J., & Cabré, Teresa. (2011). A proposed method for analysing the dynamics of cognition through term variation. Terminology, 17(1), 49– 73. Freixa, J. (2002). La variació terminològica: Anàlisi de la variació denominativa en textos de diferent grau d’especialització de l’àrea de medi ambient. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pompeu Fabra. Freixa, J. (2005). Variación terminológica: ¿Por qué y para qué? Meta, 50(4), 1492– 1421. Freixa, J. (2006). Causes of denominative variation in terminology. Terminology 12(1), 51–77. Geeraerts, D. (2006). Methodology in Cognitive Linguistics. In G. Kristiansen, M. Achard, R. Dirven, & F. Ruiz de Mendoza (Eds.), Cognitive Linguistics: Current applications and future perspectives (pp. 21–50). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 39 Geeraerts, D. (2010a). Lexical variation in space. In P. Auer, & J. E. Schmidt (Eds.), Language and Space. An International Handbook of Linguistic Variation (pp. 820– 836). Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. Geeraerts, D. (2010b). Schmidt redux: How systematic is the linguistic system if variation is rampant? In K. Boye, & E. Engeberg-Pedersen (Eds.), Language usage and language structure (pp. 237–262). Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Geeraerts, D., Grondelaers, S., & Bakema, P. (1994). The Structure of Lexical Variation: Meaning, Naming, and Context. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. Geeraerts, D., & Speelman, D. (2010). Heterodox concept features and onomasiological heterogeneity in dialects. In D. Geeraerts, G. Kristiansen, & Y. Peirsman (Eds.), Advances in Cognitive Sociolinguistics (pp. 23–40). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Goźdź-Roszkowski, S. (2011). Explorations across Languages and Corpora. Bern: Peter Lang. Hamon, T., & Nazarenko, A. (2001). Detection of synonymy links between terms: experiment and results. In D. Bourigault, C. Jacquemin, & M. C. L'Homme (Eds.), Recent Advances in Computational Terminology, vol. 2, (pp. 185–208). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Hardie, A., Koller, V., Rayson, P., & Semino, E. (2007, July). Exploiting a semantic annotation tool for metaphor analysis. Proceedings of the Corpus Linguistics 2007 conference, Birmingham, AL. Kageura, K. (2002). The dynamics of terminology. A descriptive theory of term formation and terminological growth. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Koller, V., Hardie, A, Rayson, P., & Semino, E. (2008). Using a semantic annotation tool for the analysis of metaphor in discourse. Metaphorik, 15, 141-160. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 40 Kövecses, Z. (2005). Metaphor in Culture: Universality and Variation. New York: Cambridge University Press. Kövecses, Z. (2006). Language, Mind, and Culture. A Practical Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Kristiansen, G. (2008). Style-shifting and shifting styles. In G. Kristiansen, & R. Dirven (Eds.), Cognitive Sociolinguistics: Language Variation, Cultural Models, Social Systems (pp. 45–88). Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago University Press. Lakoff, G. (1993). The contemporary theory of metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and Thought (pp. 202–251). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Langacker, R. (1999). Grammar and Conceptualization. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Lapesa, R. (1942). Historia de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Gredos. Mason, Z. (2004). CorMet: A computational, corpus-based conventional metaphor extraction system. Computational Linguistics, 30(1), 23–44. Pederson, E. (1998). Spatial language, reasoning, and variation across Tamil communities. In P. Zima, & V. Tax (Eds.), Language and Location in Space a Time (pp. 111–119). Munich: Lincom Europa. Sardinha, B. (2008). Metaphor probabilities in corpora. In S. Zanotto, L. Cameron, & M. Cavalcanti (Eds.), Confronting Metaphor in Use (pp. 127–148). Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Semino, E. (2006). A corpus-based study of metaphors for speech activity in British English. In A. Stefanowitsch, & S.T. Gries (Eds.), Corpus-based Approaches to Metaphor and Metonymy (pp. 36–63). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 41 Speelman, D., Grondelaers , S., & Geeraerts, D. (2003). Profile-based linguistic uniformity as a generic method for comparing language varieties. Computers and the Humanities, 37, 317–337. Steen, G. (2007). Finding Metaphor in Grammar and Usage. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Suárez, M. (2004). Análisis Contrastivo de la Variación Denominativa en Textos Especializados: Del Texto Original al Texto Meta. Barcelona: Institut Universitari de Lingüística Aplicada. Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Temmerman, R., & Kerremans, K. (2003). Termontography: Ontology building and the Sociocognitive Approach to terminology description. Prague CIL17- conference. http://www.hf.uib.no/forskerskole/temmerman_art_prague03.pdf. Accessed 23 April 2012. Tomasello, M. (2003). Constructing a Language. A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition. Harvard: Harvard University Press. Trim, R. (2011). Metaphor and the Historical Evolution of Conceptual Mapping. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan. Ureña, J.M., & Faber, P. (2010). Reviewing imagery in resemblance and nonresemblance metaphors. Cognitive Linguistics, 21(1), 123–149. Ureña, J.M., & Faber, P. (2011a). Strategies for the semi-automatic retrieval of metaphorical terms. Metaphor and Symbol, 26(1), 23–52. Ureña, J.M., & Tercedor, M. (2011b). Situated metaphor in scientific discourse: An English-Spanish contrastive study. Languages in Contrast, 11(2), 216–240. Metaphor and denominative variation in science 42 Authors’ addresses + emails José Manuel Ureña Gómez-Moreno Department of Modern Philology University of Castile-La Mancha Faculty of Arts Avda. Camilo José Cela, s/n, University Campus 13071 Ciudad Real, Spain josemanuel.urena@uclm.es Pamela Faber Department of Translation and Interpreting University of Granada C/ Buensuceso, 11 18071 Granada, Spain pfaber@ugr.es About the authors José Manuel Ureña obtained his PhD in Translation and Interpreting from the University of Granada. He is currently a Junior Professor at the Department of Modern Philology of the University of Castile-La-Mancha, Spain, where he teaches Translation and Academic English. His main research interests lie in (socio)cognitive semantics and Terminology, with a special focus on figurative language and English-Spanish Metaphor and denominative variation in science 43 contrastive studies. He has published in high-impact journals, such as Cognitive Linguistics, Metaphor and Symbol, Terminology, and Language Sciences. Pamela Faber holds degrees from the University of North Carolina, the University of Paris IV, and the University of Granada where she has been a full professor in Translation and Interpreting since 2001. She is the author of various articles and books on Lexical Semantics and Terminology. She is also the Head of the LexiCon research group, with whom she has carried out various research projects on terminological knowledge bases, conceptual modeling, ontologies, and cognitive semantics.