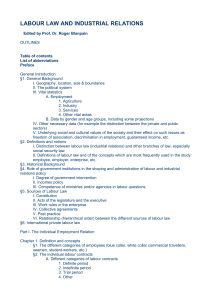

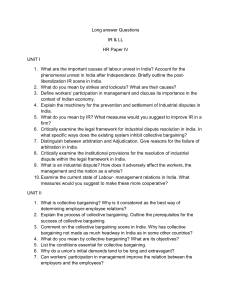

Labour Law - McGill University

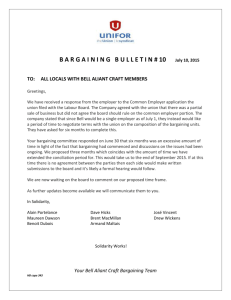

advertisement