The Historical Perspective of the English Lexicon

advertisement

The Historical Perspective of the English Lexicon

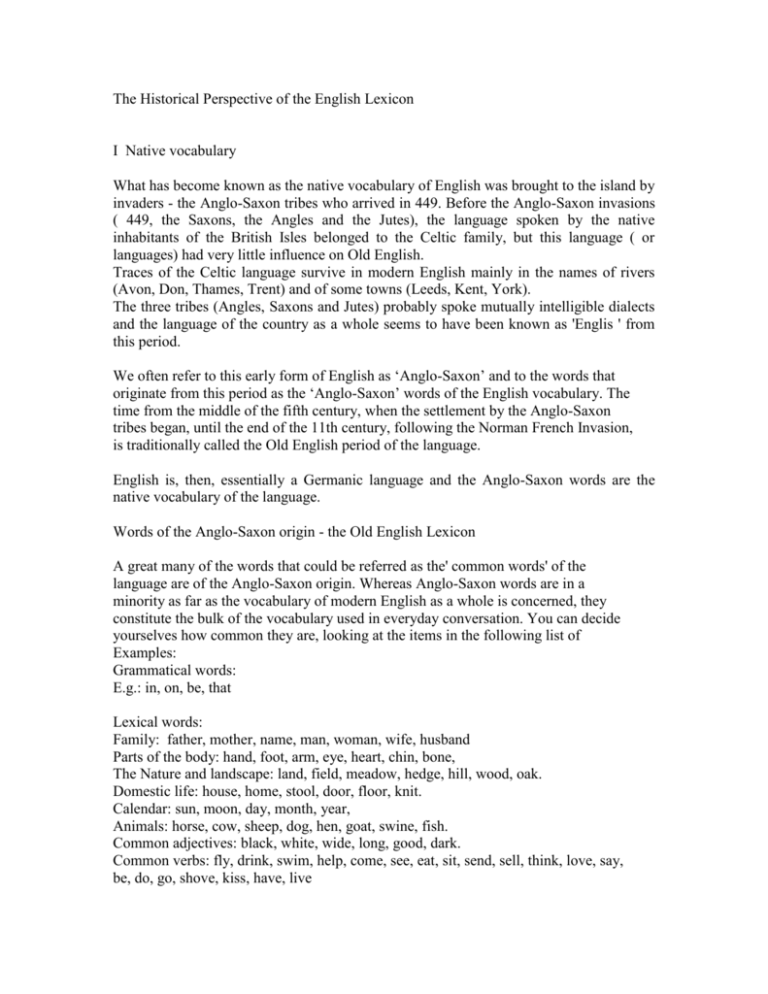

I Native vocabulary

What has become known as the native vocabulary of English was brought to the island by

invaders - the Anglo-Saxon tribes who arrived in 449. Before the Anglo-Saxon invasions

( 449, the Saxons, the Angles and the Jutes), the language spoken by the native

inhabitants of the British Isles belonged to the Celtic family, but this language ( or

languages) had very little influence on Old English.

Traces of the Celtic language survive in modern English mainly in the names of rivers

(Avon, Don, Thames, Trent) and of some towns (Leeds, Kent, York).

The three tribes (Angles, Saxons and Jutes) probably spoke mutually intelligible dialects

and the language of the country as a whole seems to have been known as 'Englis ' from

this period.

We often refer to this early form of English as ‘Anglo-Saxon’ and to the words that

originate from this period as the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ words of the English vocabulary. The

time from the middle of the fifth century, when the settlement by the Anglo-Saxon

tribes began, until the end of the 11th century, following the Norman French Invasion,

is traditionally called the Old English period of the language.

English is, then, essentially a Germanic language and the Anglo-Saxon words are the

native vocabulary of the language.

Words of the Anglo-Saxon origin - the Old English Lexicon

A great many of the words that could be referred as the' common words' of the

language are of the Anglo-Saxon origin. Whereas Anglo-Saxon words are in a

minority as far as the vocabulary of modern English as a whole is concerned, they

constitute the bulk of the vocabulary used in everyday conversation. You can decide

yourselves how common they are, looking at the items in the following list of

Examples:

Grammatical words:

E.g.: in, on, be, that

Lexical words:

Family: father, mother, name, man, woman, wife, husband

Parts of the body: hand, foot, arm, eye, heart, chin, bone,

The Nature and landscape: land, field, meadow, hedge, hill, wood, oak.

Domestic life: house, home, stool, door, floor, knit.

Calendar: sun, moon, day, month, year,

Animals: horse, cow, sheep, dog, hen, goat, swine, fish.

Common adjectives: black, white, wide, long, good, dark.

Common verbs: fly, drink, swim, help, come, see, eat, sit, send, sell, think, love, say,

be, do, go, shove, kiss, have, live

The characteristics of Anglo-Saxon words:

1) most of these words are short, consisting of no more than one or

two syllables;

2) Anglo-Saxon words are characteristically associated with the level of informality or

with colloquial language.

There is an expression in Modern English -'speaking Anglo-Saxon' -which means

'plain, blunt speaking'. Another expression - 'Anglo-Saxon words' - is a euphemism

for obscene or four-letter words (e.g. shit, arse, etc,).

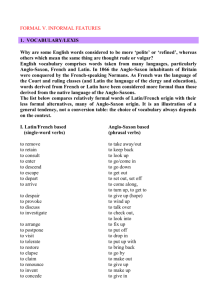

English vocabulary contains many pairs of words, one of whose members is of OldEnglish origin and belongs to the level of informality, whereas the other member is a

borrowed word and associated with more formal contexts.

lexical twins:

pluck -courage (French)

sweat -perspire (French)

guts -determination (Latin)

clothes -attire (French)

climb ascend (Latin)

begin commence (French)

book volume (French)

pride hubris (Greek)

lung pulmonary (Latin)

lexical triplets:

OE

rise

ask

kingly

holy

colloquial

F

mount

question

royal

sacred

formal

L

ascend

interrogate

regal

consecrated

learned

II Foreign borrowings

a)Scandinavian loans

The Scandinavian (Old Norse) effect on English was a result of the Viking raids which

began at the end of the 8th c. and continued for 200 years. For a while the Danes

controlled most of Eastern England in the middle of the 9th c. .By the Treaty of

Wedmore (886), the Danes agreed to settle only in the north-east third of the country

The area became known as the Danelaw

The invaders, who were mostly Danes and Norwegians, spoke dialects of Old Norse the parent language of the modern Scandinavian languages. It was a North Germanic

language related to Old English,

Unlike the Normans who were to follow them, the Scandinavian invaders never

achieved political and cultural dominance over the whole country. The Scandinavians

eventually became absorbed and assimilated into the native Anglo-Saxon culture. Their

linguistic influence was also relatively small and Old English and Old Norse had many

words in common anyway.

The linguistic effect of the period is reflected in a large number of Danish place-names

in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire,

There are over 600 place-names ending in -by ('farm', 'village', 'town'): E.g. Derby,

C;rimsby, Rugby, Naseby, etc. ,

Many place-names end in -thorp ('village'). E.g. Althorp, Astonthorpe, Linthorpe,

The ending -thwaite ('clearing)' E.g. Braithwaite, Applethwaite, ,Storthwaite,

Also family names: ending in -son, E,g, Davidson, Jackson

A number of general words entered the language: E,g, landing, take

Words using Iskl sounds were borrowed (a feature of Old Norse) -E,g. .skirt, sky, skin,

skill, etc, , The Iskl betrays their origin -the equivalent OE consonant

combination, written sc, came to be pronounced Ishl, so that, for example, shirt from

OE and skirt from Old Norse, derive from the same source-word.

Some of the commonest words entered the language at this time: E.g. both, same, get,

give, they, them, their, egg, silver, silver, raise, sick.

b) Norman French loans (the ME period).

The second, and linguistically far more significant political invasion was that of the

Normans under William the Conqueror in 1066.

1066 marks the beginning of a new social and linguistic era in Britain. The linguistic

period -the Middle English period. French was the main influence on English. Not

until Henry Bolingbroke (Henry IV) acceded to the throne in 1399 would an English

monarch have English as his native language.

Unlike Scandinavians, the French formed a cultural, social and political elite

dominating whole areas of public life, like government, the law, the church, and the life

of the court and the manor house. These were also the areas where writing had an

important function, so that for nearly three centuries English fell into comparative

disuse in the written medium: French and Latin dominated.

Over 10,000 French words came into English at that time (about 3/4 of these words are

still in the language today). Not surprisingly, these words were largely related to the

French-dominated areas of life, such as the fields of law and administration, also

medicine, art and fashion, as all the powerful and fashionable people (the kings and

nobility, people related to the structures of power) spoke French.

Words derived from French are sometimes recognizable from their characteristic

patterns of spelling, e.g. the -ity endings (felicity, equity), the -our ending (favour) or

the -ant (infant). Mostly, however, the words borrowed during the ME period have

become nativised and assimilated in English in terms of spelling and pronunciation.

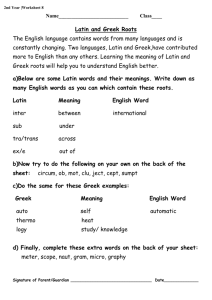

c) Earlier Latin loans.

Latin had for centuries been the language of the church in western Europe and the first

significant wave of influence of Latin on English dates back to AD 597 when the

Roman Monk St. Augustine (the first Archbishop of Canterbury) came to Kent with

the commission from Pope Gregory I to convert England to Roman Christianity

During this period, hundreds of words were borrowed into English. The new words

were mostly ecclesiastical, connected with the Church and its services, there were also

some general words. Among these earlier Latin loans, the year 1000 can be considered

a dividing landmark Up to 1000, words were mostly borrowed from spoken Latin, and

related more to practical everyday matters.

Ecclesiastical. E.g. altar, apostle, bishop, mass, monk, school

General: E.g. lily, plant, rose, study, organ.

After AD 1000, following the rebirth of learning associated with King Alfred, the

vocabulary came from written sources and was much more scholastic:

Ecclesiastical: E.g. clerk, creed, cross, demon, paradise,

salvation.

d) Later classical loans.

During and after the Renaissance (15,16 centuries) Latin became more generally the

language of learning, and along with Greek, was widely regarded as superior to the

vernacular languages of Europe like English. It was thought, that

the nearer the vernacular languages approximated to Latin and Greek, the more

'perfect' they would become. At this time a number of Latin and Greek words was

borrowed into the 'learned' vocabulary of English - a process that has continued to the

present day, especially in the scientific and medical fields. From Greek, sometimes by

way of Latin, English has borrowed agnostic, diagnosis, athlete, catastrophe,

encyclopedia, climax, etc.

Typical Latin endings:

um (quorum, referendum);

us ( campus, chorus, fungus);

a (diploma, drama, formula);

ex/-ix (index, appendix, matrix).

Typical Greek endings:

is ( analysis, crisis, synopsis);

on (automaton, neutron, phenomenon).

In modern English many technical words are formed from Latin and Greek combining

forms television (Gr.+Latin), electrocardiograph (L. (Gr.) + Gr.+ L (Gr)).

The period during and after the Renaissance was also the period when the world-wide

explorations of Englishmen began. Travelling led to contacts with other peoples and

other cultures and words were taken over from over 50 other languages.

e)Recent loans.

The English of our contemporary time is a fully developed cultural language and

borrowings no longer play the key role that had in the earlier stages of the language There

has continued to be borrowing on a smaller scale from many languages of the world. In

many cases the spelling and the pronunciation of a word

may betray its origin:

avant-garde, chic, detente (French);

rucksack, kindergarten (German);

cantata, concerto, oratorio, opera, soprano (Italian);

chocolate, cocoa, potato, tobacco, vanilla (Spanish);

pogrom, bolshevik, czar, balalaika, samovar,sputnik (Russian);

bungalow, dinghy, shampoo, cot, juggernaut (Hindi};

boomerang, kangaroo, wombat (Australian aboriginal languages)

Borrowing is a sociolinguistic process which is not always appreciated by all members

of the language community. In countries that have a language academy, there is usually

an attempt to keep the language "pure" by prohibiting borrowed words. France, for

example, has tried to prevent the use of English words in French by law. It is

nevertheless highly questionable if even law can stop a process so natural. Because all

languages borrow words from other languages. All cultures that have contact are likely

to borrow words from each other

It should be noted that within English, this century has seen an active and almost

exclusively one-way traffic from American sources to other varieties.

English has continued to borrow liberally from French. A recent source of borrowings

has been the French-dominated European Union bureaucracy. Interestingly, there doesn't

seem to have been much opposition among

English-speakers to the excessive borrowing from French If anything, British English

speakers may complain about the influx of americanisms.

But on the whole, the linguistic purity of English has always been pretty much a nonissue.