Community Services

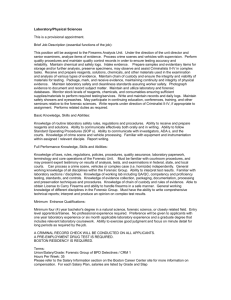

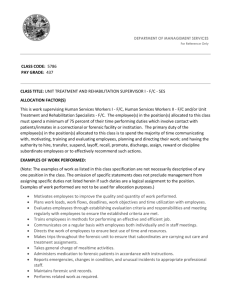

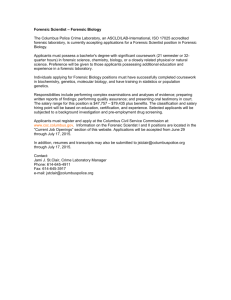

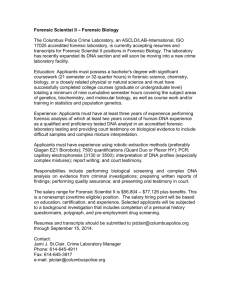

advertisement