Subject profile objectives

Guidelines for the wording of

subject profile objectives

At the Courses Committee meeting of 14 April 2005 the following motion was passed:

“The Faculty of Science and Agriculture Courses Committee agreed to note the “Writing of

Instructional Objectives ” guidelines and recommended that their use be encouraged but not made compulsory for writing subject profile objectives” (CCS 05/32)

At a subsequent meeting of the ITDC it was decided that a summary of the relevant documentation on the writing of objectives for subject profiles be produced to provide guidance to Subject Coordinators of IT subjects, on the writing of objectives for their subjects.

Rationale

There has been debate and confusion about the concept of objectives and the purposes for which they are used. This debate has ventured into areas such as the use of instructional and/or behavioural objectives to prepare items of curriculum that are not directly relevant to the discussion at hand. While academic regulations are not always perfect, they do give a flavour for what is required. The current regulations (as embodied in

CASIMS) state that:

“The intention of this field [objectives] is to identify outcomes in terms of the skills, attributes and knowledge that a student who has successfully completed this subject should possess. While outcomes should clearly relate to the syllabus and assessment, they should not be simply a list of activities either undertaken in the subject or able to be undertaken by the graduate.”

This forms a reasonable working basis for the writing of subject profile objectives. Unfortunately, when one analyses what is sometimes provided in the objectives field, there is a wide variation in the level of consistency with this working definition. There are several problems that manifest themselves. These include:

Use of verbs that imply an ‘affective’ domain ie an emotional or abstract state that is not readily observable and hence assessable. For example : “appreciate some of the myths surrounding object-

orientation while retaining a genuinely optimistic evaluation of its prospects as a practical tool for software engineers” or “feel confident that they have a sufficient depth of knowledge to enter the practical field of objectoriented technology” or “be aware of …”. The use of such words as “appreciate”,

“feel”, “understand” or “know” results in statements that are difficult, if not impossible, to assess.

Emphasis on elements that are largely at the bottom level of cognitive demand ie statements that simply expect knowledge or comprehension. For example: “explain the mechanisms for …”, “recognise

…”, “list the …”. The problem here is not that such statements of outcomes are inappropriate but rather that the predominance of these sorts of statements inappropriately neglects higher order elements. The objectives field in a subject profile ought to be a short list (5 or so according to the manual) which should favour the higher levels of cognition over the lower. Too many subject profiles never venture beyond knowledge and comprehension.

Too few or too many statements of outcomes ie profiles that have only two objectives run the risk of

generalising to the point where the statements may be interpreted in far too many ways to be useful or do not cover the full set of expected outcomes for the subject. On the other hand having twenty objectives either represents detail that is more appropriate at the day to day teaching/learning level or indicates that far too much is being expected in the subject. It is clearly impossible to categorically give a number but again the academic guidelines of 5-10 is a statement of what is considered reasonable.

Use of multiple objectives in the one statement Sometimes this is done by combining verbs; for example, “research and report on how …” or “analyse, document and reflect on …”. At other times it combines items that are really separate skills, for example “be able to use tools to assist in the construction of the first stages of a compiler and know the relationship between these tools and the abovementioned abstract machines ”. While the former is justifiable and may show a gradation of cognitive levels associated with some subject matter, the latter is less so. In some cases, the use of multiple conjunctions is a sign that the objective has not been written at a sufficiently general level for example “prepare and give both formal and informal, and both written and oral presentations of a technical nature to a varied audience”

Phrasing suitable objectives

Unfortunately, one of the critical problems that one encounters with the writing of objectives is that the ‘stem’ that the University chose to implement ie “Upon successful completion of this subject, students should:” makes it extremely awkward to phrase objectives without resorting to a techniqu e that Ken Lodge calls “mangling”; phrases such as “be able to” or “have carried out” etc added immediately after the stem to allow the complete sentence to make sense. There is no easy way around this problem. Mangling may need to take place until the

University changes the stem.

Given the discussion above, the recommendations for the writing of statements of outcomes would be to:

1. Give a clear indication of the essential elements of the subject

2. Avoid the use of affective terms such as appreciate, know, understand, feel etc

3. Link the expectation to some way that it can be demonstrated

4. Include the full range and especially higher level, of cognitive skills

5. Ensure that the set of statements adequately covers the expectations for the subject

6. Write statements that are of a macro rather than a micro nature

7. Avoid arbitrary combinations of outcomes

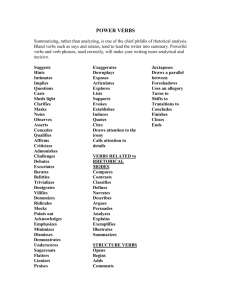

Cognitive levels and suitable action verbs

The taxonomy of cognitive behaviours consists of:

Knowledge (the lowest level behaviour)

Comprehension

Application

Analysis

Synthesis and

Evaluation (the highest level behaviour)

Below is a brief explanation of the different behaviours you can expect to observe in students working at these levels, and a list of suitable action verbs you can include in corresponding objectives.

Knowledge – behaviours which emphasise remembering, recognition and recall at a later date.

Suitable verbs: ‘recall’, ‘list’, ‘define’, ‘state’ or ‘recognise’. (Do not use ‘know’, ‘understand’ or ‘remember’).

Comprehension – behaviours which emphasise understanding, perception and insight.

Suitable verbs: ‘outline’, ‘paraphrase’, ‘describe’, ‘match’, ‘predict’, ‘name’, ‘interpolate’, ‘label’, ‘extrapolate’,

‘identify’, ‘interpret’, ‘locate’, ‘translate’, ‘tabulate’, ‘illustrate’, ‘sketch’, ‘draw’, ‘graph’ or ‘give examples of’.

Application – behaviours which emphasise using something in a specific manner.

Suitable verbs: ‘apply’, ‘connect’, ‘show’, ‘mix’, ‘demonstrate’, ‘stir’, ‘use’, ‘measure’, ‘perform’, ‘set up’, ‘relate’,

‘filter’, ‘develop’, ‘evaporate’, ‘transfer’, ‘photograph’, ‘construct’, ‘calibrate’, ‘explain’, ‘prepare’, ‘infer’, ‘compute’,

‘solve’, ‘record’, ‘tell’, ‘present’, ‘participate in’ or ‘report’.

Analysis – behaviours which emphasise the breaking down or separation of a whole into its component parts.

Suitable verbs: ‘analyse’, ‘interpret’, ‘identify’, ‘separate’, ‘break down’, ‘discriminate’, ‘distinguish’, ‘detect’ or

‘categorise’.

Synthesis – behaviours which emphasise the combining together of separate elements to form a more complete whole. Synthesis is the opposite of analysis.

Suitable verbs: ‘combine’, ‘restate’, ‘modify’, ‘summarise’, ‘estimate’, ‘precis’, ‘generalise’, ‘conclude’, ‘derive’,

‘revise’, ‘organise’, ‘design’, ‘deduce’, ‘classify’, ‘formulate’, ‘propose’, ‘compose’ or ‘assemble’.

Evaluation – behaviours which emphasise the combination of all of the previous five categories. As its name suggests evaluation is concerned with making judgements about value

Suitable verbs: ‘evaluate’, ‘qualify’, ‘judge’, ‘decide’, ‘justify’, ‘choose’, ‘verify’, ‘assess’, ‘contrast’, ‘criticise’,

‘select’, ‘debate’, ‘defend’, ‘support’, ‘dispute’, ‘attack’, ‘question’, ‘avoid’, ‘seek out’, ‘appraise’, ‘compare’, or

‘determine’.