week-1

advertisement

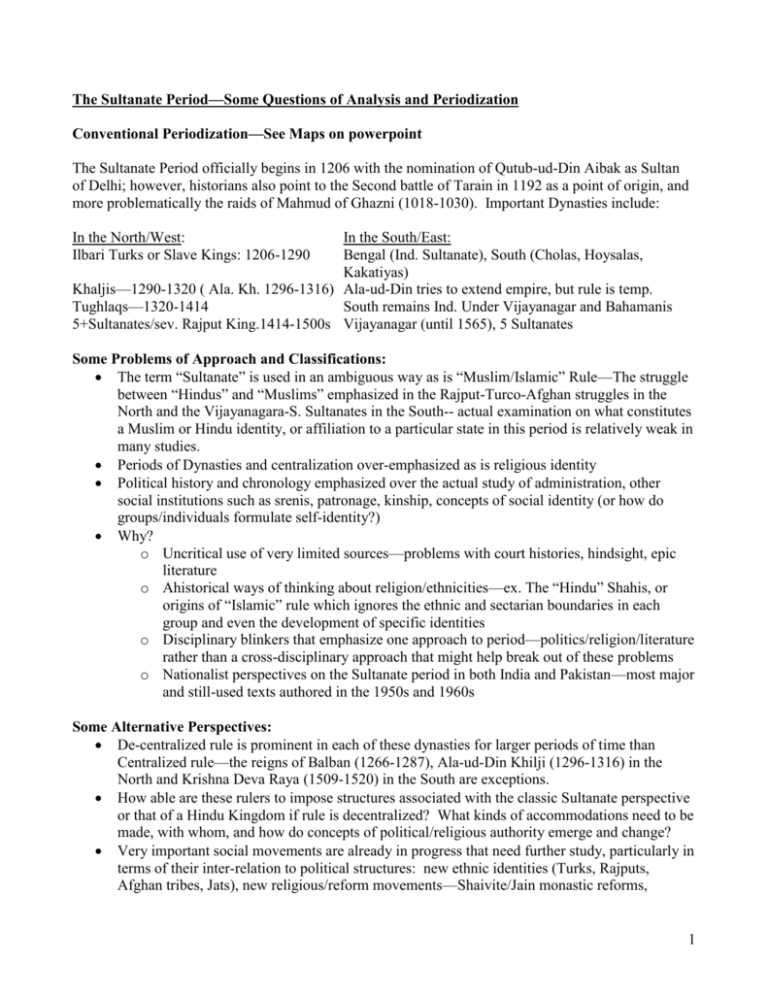

The Sultanate Period—Some Questions of Analysis and Periodization Conventional Periodization—See Maps on powerpoint The Sultanate Period officially begins in 1206 with the nomination of Qutub-ud-Din Aibak as Sultan of Delhi; however, historians also point to the Second battle of Tarain in 1192 as a point of origin, and more problematically the raids of Mahmud of Ghazni (1018-1030). Important Dynasties include: In the North/West: Ilbari Turks or Slave Kings: 1206-1290 In the South/East: Bengal (Ind. Sultanate), South (Cholas, Hoysalas, Kakatiyas) Khaljis—1290-1320 ( Ala. Kh. 1296-1316) Ala-ud-Din tries to extend empire, but rule is temp. Tughlaqs—1320-1414 South remains Ind. Under Vijayanagar and Bahamanis 5+Sultanates/sev. Rajput King.1414-1500s Vijayanagar (until 1565), 5 Sultanates Some Problems of Approach and Classifications: The term “Sultanate” is used in an ambiguous way as is “Muslim/Islamic” Rule—The struggle between “Hindus” and “Muslims” emphasized in the Rajput-Turco-Afghan struggles in the North and the Vijayanagara-S. Sultanates in the South-- actual examination on what constitutes a Muslim or Hindu identity, or affiliation to a particular state in this period is relatively weak in many studies. Periods of Dynasties and centralization over-emphasized as is religious identity Political history and chronology emphasized over the actual study of administration, other social institutions such as srenis, patronage, kinship, concepts of social identity (or how do groups/individuals formulate self-identity?) Why? o Uncritical use of very limited sources—problems with court histories, hindsight, epic literature o Ahistorical ways of thinking about religion/ethnicities—ex. The “Hindu” Shahis, or origins of “Islamic” rule which ignores the ethnic and sectarian boundaries in each group and even the development of specific identities o Disciplinary blinkers that emphasize one approach to period—politics/religion/literature rather than a cross-disciplinary approach that might help break out of these problems o Nationalist perspectives on the Sultanate period in both India and Pakistan—most major and still-used texts authored in the 1950s and 1960s Some Alternative Perspectives: De-centralized rule is prominent in each of these dynasties for larger periods of time than Centralized rule—the reigns of Balban (1266-1287), Ala-ud-Din Khilji (1296-1316) in the North and Krishna Deva Raya (1509-1520) in the South are exceptions. How able are these rulers to impose structures associated with the classic Sultanate perspective or that of a Hindu Kingdom if rule is decentralized? What kinds of accommodations need to be made, with whom, and how do concepts of political/religious authority emerge and change? Very important social movements are already in progress that need further study, particularly in terms of their inter-relation to political structures: new ethnic identities (Turks, Rajputs, Afghan tribes, Jats), new religious/reform movements—Shaivite/Jain monastic reforms, 1 Islamization among Turkish-Mongol groups, New devotional/bhakti reforms, the retreat of Jainism/Buddhism, diffusion of Sufis throughout with theologies that span orthodox and nonorthodox Islamic/Hindu/folk perspectives The flux of political rule unleashes a huge demand for military labor—what does this do to the new identities mentioned above? How does the shift to cavalry-based war change things? New Economic formations emerging—Rice cultivation in Bengal, textile imports from the South, Slave markets due to the presence of war captives, new demands for horses and weaponry—How doe these interact with the state/society? Continuation of older patterns ignored—the continuing competition between local groups and their outcomes, the dominance of local (and new) land-holding groups in some areas and their ability to negotiate with the state, the persistence of matrimonial alliance across boundaries as a way of establishing patronage ties and as a reflection of hierarchy, older ideas of warrior conduct in each culture—whether Turkic (pre-islamic) or Rajput. What do we know about State Structures in the Sultanates and contemp. kingdoms, based on existing sources? See work of S. Digby, Kumar, M. Habib, P. Hardy, S. Rizvi for details. The Sultanates, like their neighbors, were conquest states—once established they depended on both armed coercion and negotiation to survive, overdoing either strategy limited desired outcomes Sultanate rulers gradually adapted from ideas of administration used in Iran/Turan to local usages—the ideal of the court histories also shows actual accommodation to unavoidable realities The Turco-Afghan dynasties were not sufficient in numbers to effectively create a centralized state on their own, therefore they relied on two strategies: 1) incentives to immigrants from the north-west to immigrate (greatly aided by Mongol expansion/raids) ; 2) establishing connections with local elites (the dehqans, rais, rajas) to govern The modified Iqta system emerged as the major unit of governance—all lands divided into Khalisa (crown) or Iqtas (revenues earmarked for officers/military commanders), but it was prone to abuse and greatly limited the authority of the ruler. The classic sharia model described in history remained a theoretically desired goal, but in actual practice accommodation to local realities was the norm. Equally, the cultural borrowings of Imperial Persia with its emphasis on the King as the “shadow of God,” rigid ideas of class and etiquette, the idea of a hereditary kingship was more useful to the ruler. Despite objections from some ulema, non-Sunnis were accepted largely as “Dhimmis” or protected minorities and Hindus were viewed as Ahl-e Kitab, the limits of enforcing the sharia outside of garrison towns and qasbas was acknowledged early on. This had some practical uses in ensuring some income from the jizya tax, higher taxes based on income from the Muslim nobility, and also policing the limits of the elite social identity—in other words conversion, contrary to political claims new and old, was never the goal. Similar modes of accommodation in other states, patronage of Brahmins does not necessarily mean the state was a theocracy. While revenue could be fixed, limits had to be placed on its collection—peasants were not easily cowed and intermediaries were crucial to securing revenue rights for both groups. Sultans constantly faced threats—most often from their own ethnic groups (chehelgan) and therefore quickly sought alliances with other groups to balance the influence in court— Immigrants, Local elites, Religious authority figures. The same holds true for non-Turkish dynasties. 2