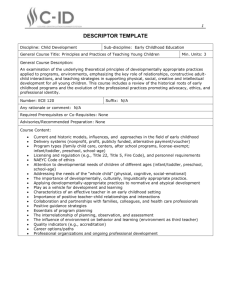

A Program-Wide Model for Supporting Social Emotional

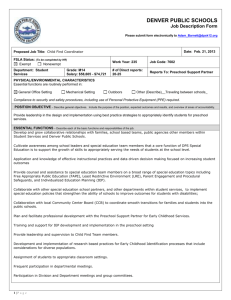

advertisement