The English Vowel Space of Filipino Children–Christine C. Espedido

advertisement

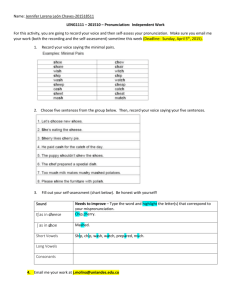

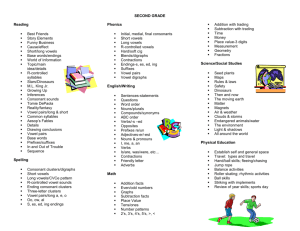

The English Vowel Space of Filipino Children Christine C. Espedido Department of Linguistics, University of the Philippines, Diliman tintin7978@hotmail.com ABSTRACT This paper describes the acoustic characteristics of English vowels, as spoken by Filipino elementary school students. Acoustic measures of duration and first and second formant frequencies were obtained from 30 children, while producing words containing the vowels /i, ɪ, e, ɛ, æ, a, ɔ, o, ʊ, u, ʌ/ in English, representing both genders. In characterizing these vowels, I also compared the data to a vowel mapping of the Filipino vowels of the children and to the vowels of 46 American children from the data of Hillenbrand et al., [J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 97, 3099-3110 (1995)]. The analysis of this study is that Filipino children could produce or 6 out of the 11 English vowels. The Philippine English vowels are /a/, /e/, /ɛ/, /i/, /ɔ/ and a near-close near back rounded /u/. Moreover, Filipino English vowels were 62% shorter than that of the American L1 speakers. This paper is a first approximation of the sounds of Philippine English as spoken in the elementary grades in a particular public school and explores how and why they differ from the sounds that native English speakers produce. Keywords: vowel space, acoustic phonetics, Filipino- English. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Background Any L1 or L2 teacher in any multilingual country must be able to have a good grasp of the learner’s first language and the target language to become an effective language teacher. A good knowledge of acoustic phonetics can also help in this regard. Knowledge of the acoustic cues accompanying speech production of the source and target language and a sense of where the learners are, can prepare the language teacher better for his or her work of facilitating the transfer of L1 skills to the L2. In this paper, a representative vowel inventory of English as spoken by Filipino children will be presented. I will address the problem of mapping the English vowels to the Filipino vowels of the children. To describe further, the data will be compared to the vowels of 46 American children. 1.2 Previous studies English is a global language and it is essential for communication. However, the status of the English language in the world today is different from what it used to be. It is a property of the world and does not belong to native-speakers alone but to all speakers of English worldwide. Philippine English is a variety of English used in the Philippines by the media and the vast majority of educated Filipinos. Philippine English exists and it is a legitimate variety of English, that is developing its own standards. For global competitiveness, English proficiency is needed. Does the “Global Filipino” still have an edge with Philippine English? To answer this question, we need to scrutinize the status of Philippine English. Bautista [1] made an inventory of deviations in the sentences in a corpus and focused on grammatical features which now have become acceptable and part of the standard Philippine grammar. The analysis identified deviations in subject-verb agreement, in the use of articles, prepositions, tenses, mass nouns and count nouns, and in pronoun-antecedent agreement. With regards to pronunciation, she states that “Philippine English has not been stabilized and it still constitutes a multiplicity of idiolectal pronunciations that do not make up a distinct standard variety.” As Gonzales [2] tried to determine the features of the spoken and written English by educated Filipinos over the years, he had found that there has been a diminution of achievement among today’s generation of learners. These works of Bautista and Gonzales reflect on many other studies, capitalizing on performance slip and acquisitional deficiency of the Philippine English. They call for innovations in methodology and competence in teachers. Works done by Martinez [3] and Mata and Soriano [4] deal with raising the standards in the teaching of English in the Philippines. Martinez used an approach of using Filipino models instead of American models or the “integrative approach” in teaching English pronunciation with the use of drills and exercises. Martinez states that the Tagalog speaker will have no difficulty with the vowels /i, e, a, o, u/ of what she calls Standard Filipino English since these are found in his language. But, that speaker will experience difficulty with /, æ, ə, ʊ, and ɔ/. The English vowel / ɪ / is usually replaced by the Tagalog /i/ or /e/, / æ / with /e/ or /a/, / ʊ/ with /u/, / ɔ/ by /o/ and / ə/ by Tagalog /a, e, i, o, u/. For Martinez, the Tagalog vowel phonemes in her dataset are /a, e, i, o, u/ whereas the Standard Filipino English vowel phonemes are /i, ɪ, e, æ, ə, a, u, ʊ, o, ɔ/. 2.2 Procedure Similarly, Mata and Martinez provided drills and techniques to improve oral English. They said that it is insufficient to just merely hear the sound and that it will be necessary for the student to know what to do with the lips, the tongue, and the vocal organs; to know the length of the sound, and other characteristics which will help him produce the sound correctly without substituting the vernacular counterparts. 2.2.1 Data Collection This paper agrees with the idea that the pronunciation quality does not solely depend on the ability to produce the words correctly; it also depends on the knowledge of how the words should be pronounced. Here, I will be using acoustic analysis which can show the spectral distribution and other acoustic dimensions of sounds. The acoustic signal bridges the acts of speech production and speech perception. Acoustic phonetics can suggest appropriate phonological features for descriptive use. There is limited research done in the field of children’s speech analysis and recognition in the Philippines. Even though children’s language learning is highly important, it is relatively hard to obtain effective tools for pronunciation assessment due to the special characteristics of children’s speech and the limited availability of children’s speech data in the speech research community. For example, children’s speech is characterized by higher pitch and formant frequencies in comparison with adults’ speech. Understanding the characteristics of children’s speech can help devise strategies for testing and training speech perception and production skills. This paper aims to describe the acoustic characteristics of English vowels as spoken by Filipino children. To be able to effectively describe the vowel inventory of the target language, it is necessary to highlight its acoustic similarities and differences to the vowels of their mother tongue- Filipino [5]. Delos Reyes et al [6] mentioned that although orthographically there are five vowels in Filipino, there are only four sounds at the acoustic level. These vowel phones are “a” [a], “i",[ ɪ], “e” [ɛ], and /Y/. Of these vowels, /a/ is the most invariant. /i/ and /e/ are two distinct sounds. ‘o’ and ‘u’ are pronounced as the nearclose near-back rounded vowel /Y/. The last sound was found to be lower than /u/ and /i/ but higher than /o/ and /e/ based on the IPA index. 2. METHOD 2.1 Participants Total subjects recorded were 30 elementary school students attending a public school in Quezon City coming from Grades 4, 5, and 6. Each subject is a member of the first section of each grade level. Gender balancing was possible with all groups. Each group had 5 males and 5 females. The age range of the Grade 4 students is from 9 to 10 years old, the Grade 5 students are from 10 to 11 and the Grade 6 students are from 11 to 12 years old. Twelve English vowels were supposed to be analyzed, as spoken by Filipino children and compared to the data by Hillenbrand et al. However, the researcher found one vowel, /ɝ/ in Hillenbrand et al’s data that seemed incomparable to any of the sounds in the data collected in this paper. Thus the present dataset is restricted to the vowels /i, ɪ, e, ɛ, æ, a, ɔ, o, ʊ, u, ʌ /. Audio recordings were made of subjects reading 2 word lists. The first word list contains 22 English monosyllabic words, 2 tokens for each of the 11 vowels of American English: /i, ɪ, e, ɛ, æ, a, ɔ, o, ʊ, u, ʌ /, as shown in Table I. The second word list contains 20 Filipino words, 4 tokens for each of the 5 Filipino vowels: /a, e, i, o, u/, as shown in Table II, with stresses at varying positions. This data set has a total of 42 tokens per subject. Table I. Vowel tokens for acoustic analysis – English Vowels Tokens i feet teeth ɪ bit hit e bait fake ε bet get æ cat map a lock knock ɔ caught chalk o boat coat ʊ book pull u boot cool ʌ but nut Table II. Vowel tokens for acoustic analysis – Filipino Vowel Tokens “i” ibon itim putik puti “e” tenga relo balde ate “a” bata kanta bantay lata “o” bola bodega buntot tito “u” usok ubo pintura sinturon The recordings were done in a quiet classroom at the Quirino Elementary School. The read speech data was recorded using a Sony IC Recorder, ICD-P520. Each utterance was recorded in an individual .wav 16-bit sound file at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz. Since the room where the recordings were conducted was not sound-attenuated, the data had to undergo a noise removal process using NCH WavePad sound Editor. 2.2.2 Data Analysis Praat scripts were written to facilitate automatic acoustic measurements of the data. All sound files and textgrid files were hand-checked for accuracy. The following acoustic measurements were made: duration of individual phonemes and the first two formants (F1 and F2) of the vowels of interest. Extreme outliers of formant analyses were eliminated. 2.3 RESULTS vowels of the students from grades 4 and 5. The mean duration of the vowels of the grade 6 students is 45 ms longer than the mean duration of grades 4 and 5 students. One of the goals of this paper is to try to determine if the spoken English vowels of the Filipino children are affected by their L1 (Filipino) vowels by analyzing and comparing their acoustic characteristics. 600 tokens of the Filipino vowels were recorded and analyzed but only 300 of the tokens were selected for investigation. The tokens involve the vowels, “a”, “e”, “i”, “o”, “u”. In the analysis, it was found out that the means of the durations of the vowels of Filipino-English (168ms) and Filipino (166ms) vowels are just the same. 2.3.1 Duration (ms) of American and Filipino-English and Filipino vowels as spoken by Filipino children Vowel Duration 300 Since, vowel duration may be expected to contribute to the perceptual identification of vowel tokens by English listeners, I measured vowel duration in each of the 660 tokens in my data and plotted the mean vowel duration for each of the eleven types. 200 ms The English vowel durations of Filipino children speakers are shorter than that of the American L1 speakers (with differences of means between 65-152 ms). The duration of the Filipino children’s English vowels range between 151 to 195 ms, compared to the range of 234-322 ms for American L1 speakers. This means that Filipino English vowels were 62% shorter than that of the American L1 speakers. 250 150 Series1 100 50 350 300 0 American Filipino-English Filipino 250 200 4 5 6 American 150 Figure 2. Average Duration (ms) of American, FilipinoEnglish and Filipino vowels as spoken by Filipino children. Table III. Average durations of English vowels produced by 30 Filipino children and 45 American children at Hillenbrand et al’s data. 100 50 Duration Vowels 0 /ε/ /ʌ/ /U/ /I/ /u/ /i/ /o/ /a/ /e/ /Ɔ/ /æ/ Figure 1. Average duration (ms) of English vowels as spoken by Grades 4, 5 and 6 Filipino and American children. The four short vowels with short durations in American English are / ɪ, ɛ, ʌ, ʊ/ (with means between 234-248 ms), while the long vowels are /i, e, æ, ɔ, o, u, a/ (with means between 278322 ms). When the vowels are ordered from short to long, the increment between adjacent vowels is not more than 19 ms (which is the difference in mean vowel duration between /u/ and /i/). If we now consider the English vowel durations of the thirty grades 4, 5 and 6 Filipino children, we notice that the vowels of the grade 6 students are the longest as opposed to that of the American Filipino i 297 160 ɪ 248 151 e 314 191 ε 235 170 æ 322 177 a 311 161 ɔ 319 167 o 310 195 ʊ 247 162 u 278 165 ʌ 234 152 Table IV. Average F1 frequencies (Hz) of English vowels produced by 30 Filipino children and 45 American children in Hillenbrand et al’s data. F1 Vowels American Filipino Table VII. Formant frequencies (Hz) of Filipino stressed and unstressed vowels produced by 30 Filipino children Vowels F1 F2 “i" 446 2498 “e” 630 2262 i 452 471 ɪ 511 478 “a” 873 1590 e 564 500 “o” 606 1222 ε 749 668 æ “u” 482 945 717 952 a 1002 938 ɔ 803 731 o 597 519 ʊ 568 496 u 494 487 ʌ 749 864 Table V. Average F2 frequencies (Hz) of English vowels produced by 30 Filipino children and 45 American children in Hillenbrand et al’s data. 2.3.2. Formant Frequencies According to Ladefoged [7], the best way of describing vowels is not in terms of the articulations involved, but in terms of their acoustic properties. And the most important acoustic properties of vowels are the formants which can be readily seen in sound spectrograms. Therefore the first and second formant frequencies (resonant frequencies of the vocal tract) were taken. F1 corresponds inversely to the height dimension (high vowels have a low F1 and low vowels have a high F1). F2 corresponds to the advancement (front/back) dimension (front vowels have high F2 and back vowels have low F2). F2 Vowels American Filipino i 3081 2961 ɪ 2552 2790 e 2656 2410 ε 2267 2191 æ 2501 1611 a 1688 1475 ɔ 1210 1225 o 1137 951 ʊ 1490 963 u 1345 967 ʌ 1546 1518 Table VI. Average durations (ms) of Filipino vowels produced by 30 Filipino children Vowels Filipino “i" 169 “e” 165 “a” 160 “o” 181 “u” 158 Figure 3. Average values in Hertz of F1 and F2 of American English vowels as spoken by 46 children (Hillenbrand et al [10]) ; “i”=/i/, “ɪ”=/ɪ/, “e”=/e/, “E”=/ɛ/, “æ”=/æ/, “a”=/a/, “c”=/ɔ/, “o”=/o/, “”U”=/ʊ/, “u”=/u/, “ʌ”=/ ʌ/. Figure 3 shows the mean of the F1-F2 of all the English vowels of 46 American children in Hillenbrand et al’s data. The distributions of measured formants in this plot, corresponds closely to the distributions of phonetic values. However, the values are higher compared to the vowels of adults, considering the fact that the subjects in this particular analysis are children. Figure 4. Average values in Hertz of F1 and F2 of English vowels as spoken by 30 Filipino grade school children “i”=/i/, “ɪ”=/ɪ/, “e”=/e/, “E”=/ɛ/, “æ”=/æ/, “a”=/a/, “c”=/ɔ/, “o”=/o/, “”U”=/ʊ/, “u”=/u/, “ʌ”=/ ʌ/. Figure 4 shows the mean of the F1-F2 of all the English vowels of Filipino children. The Filipino children’s vowels show tight clustering, and therefore little spectral distinction between intended /u/, /ʊ/ and /o/. Similarly, there is hardly any spectral difference between /æ/, /ʌ/ and /a/, nor between /i/ and /ɪ/. The vowel /e/ is a mid-front unrounded vowel like the /e/ of American English, as well as the vowels /ɛ/ and /ɔ/. 2.4 DISCUSSION The F1/F2 formants of the vowels of American children in Hillenbrand et al’s data are slightly higher in frequency than those of the Grades 4, 5 and 6 Filipino children, speaking English. Also, the American children’s vowels showed longer durations (62%) than Filipino-English as spoken by the Filipino children. These differences may be observed in the mean formant frequencies and duration given on Table III. This paper sought to determine if the Filipino (L1) vowels affects the production of English (L2) vowels as spoken by Filipino elementary school children. As expected, in the Filipino-English and Filipino vowel space, considerable overlapping of areas is indicated, particularly between [o], [], and [u] of Filipino-English and [u]-Filipino. The Filipino children’s English vowels show tighter clustering, and narrower space, and therefore there is little distinction between /i/ and /ɪ/ of Filipino-English and the “i” of Filipino. The comparison of F1 means for the Filipino English /i/, /ɪ/, and “i” of Filipino, using ANOVA provided evidence of a meaningful difference [F=8.91; p<0.05]. We can say that these three vowels have different vowel height. The Filipino-English /i/ is slightly more back than Filipino-English /ɪ/ and Filipino “i”. Similarly, the vowels /æ/ (which is a low front vowel in American English), /ʌ/ (which is in the mid central position) and /a/ are articulated in the low-back region together with the Filipino “a’. A comparison of F1 means for the vowels /æ/ and /a/ using student’s t test provided no evidence of difference between the two. from individual words. Therefore, for this study, the Filipino vowels of the Filipino children are /a, e, i, o, and u/. On the other hand, the Filipino-English vowels also include the vowel /ɔ/. It is different from the Filipino vowels “o” nor “u” for it occupies a different area in the vowel space, from Figure 7, and from the evidence using ANOVA, [F=119.58;p<0.05]. The Filipino-English vowels are /a/, /e/, /ɛ/, /i/, /ɔ/ and a near-close near back rounded /u/ which is the vowel /Y/ in Delos Reyes et al’s data. 2.5 CONCLUDING REMARKS Figure 6. Plot of Mean Values in Hertz of F1 versus F2 of the Filipino Vowel Space of Filipino children With the inventory in Figure 6, we could see that the Filipino children could produce or approximate 6 out of the 11 English vowels. As for the other sounds, substitutions are being made by Filipino learners of English, that could result into serious confusion. For example, the substitution of /ɪ/ for /i/ as observed in children’s pronunciation of the word “bit” with /bi:t/ instead of /bɪt/, of the word “map” with /map/ instead of /mp/. Such “errors” can be noticeable by just plain hearing it. Now that a phonetic data analysis has provided us with the acoustic data to differentiate there variable pronunciation in English, the next step would necessarily be on how to view these variable pronunciation in Philippine English. Is this a bad thing or a good thing? This paper however is not prepared to deal with this controversy at this time. 3. REFERENCES [1] Bautista, L. 2000. Defining Standard Philippine English: It’s Status and Grammatical Features. Manila, Philippines: De La Salle University Press, Inc. p. 72-75. [2] Gonzales, A.. Jambalos, T., and Romero, C. 2003. Three Studies on Philippine English across Generations: Towards an Integration and Some Implications. Manila, Philippines: De La Salle University Press, Inc. p. 43-44. [3] Martinez, N. 1975. Standard Filipino English Pronunciation. Manila, Philippines: Navotas Press. [4] Mata, L. and Soriano, I. 1967. English Pronunciation for the Filipino College Student: Theory, Technique and Practice Material on Sound, Rhythm and Intonation. Quezon City, Philippines. Figure 7. Plot of Mean Values in Hertz of F1 versus F2 of the Filipino vowels “o” and “u” and the English vowel /ɔ/ as spoken by Filipino children. With the plot of the formant frequencies of the Filipino vowels as spoken by the Filipino children on Figure 7, this paper contradicts the study done by Delos Reyes et al [6] that proposes that there are only four sounds in Filipino, which are /a/,/e/,/i/ and /Y/, where “o” and “u” are pronounced as the near-close near back rounded /Y/. As seen in Figure 7, the Filipino vowels “o” and “u” are in different areas in the vowel space. One explanation for the difference may be because Delos Reyes et al’s data was taken from a sentence reading material whereas this paper’s data came [5] Oppelstrup, L., Blomberg, M., and Elenius, D., 2005. Scoring Children’s Foreign Language Pronunciation. In Proceedings of FONETIK, Department of Linguistics, Goteborg, University. p.51 [6] Delos Reyes, J., Santiago, P.J., Tadena, D., Zubiri, L.A. 2009. Acoustic Characteristics of the Filipino Vowel Space. In Proceedings of the 6th National Natural Language Processing Research Symposium. De la Salle University, Manila, Philippines. [7] Ladefoged, P., Phonetic Data analysis: An Introduction to Fieldwork and Instrumental Techniques. 2003. Oxford, UK. Blackwell Publishing. p. 104-105.