Week 5

advertisement

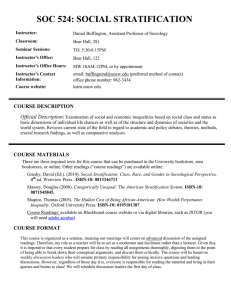

Thinking About Stratification: Week Five A funny thing happened on the way to class this past week—they closed the university. This allowed me to review the readings for this past week (I still have the weekend before our next meeting) and to make some additional progress on my class project—the analysis of race, class, and gender gaps in personal earnings (reported in the Current Population Survey, 19582008, with special attention to the 2001 survey and, eventually, earlier surveys that have data on annual earnings, unionization, firmsize, and self-employment). The latter I will save for a future discussion, but I did think about how I define race, class, and gender and how that relates to the problems of defining a base for social inequality. There are actually two issues here. First, how do we decide what "goodies" are? Second, what elements or essential conditions or processes do we identify as the basis of inequality (or process through which inequality is established or sustained)? This is a somewhat different set of issues from the "distributional" perspective that Grusky defends, but it is intended to encompass both distributional and relational perspectives on inequality. On defining "goodies" we have a series of articles dealing with occupations or classes in various forms. In some cases, these occupations are seen as the foundation for distributing other types of goodies—prestige, solidarity, or income. In some cases (which we will discuss more fully when we talk about status attainment) it seems that occupations are the "goodies" or are convenient markers for what might be considered "socioeconomic status" (which is the goody). We also have Weeden and Weeden et al, who see income or earnings as the "goodies" and view occupation (and occupational closure) as the basis or process which impedes the otherwise "market forces" that seem to be taken for granted by most of these folks. Here we should consider the exent to which prestige or socioeconomic status or jobs are an end in themselves or a means to end (value rational or instrumental rational orientations, as described by Weber). Economists and sociologists who hang out with economists (Grusky, Weeden, Sørensen, and Sen from this week, but Wright should also be included here) all seem to assume that there are markets that are driven by personal preferences and "laws" (e.g., supply and demand, falling rate of profit) that would determine prices and various ways of representing "goodies" if it were not for things (e.g., closure, rents, exploitation, and the five sources of "parametric variation" identified by Sen, pp. 236-7). This way of thinking about distributional mechanisms—as deviations from what the laws of supply and demand suggest, seems to be peculiar to economists (and sociologists who spend too much time with economists). The old guard (Blau and Duncan, Trieman, Featherman and Hauser, Hodge, and even Goldthorpe and Hope) are often focused on what seem like conceptual issues but are often methodological issues of reliability and validity in the construction of measures. These folks also seem to believe in markets and in individual preferences, but they seem to reduce social structure to social-psychological (e.g., deference, status politics, expressions of esteem or social honor) principles that resemble Weber (or George Herbert Mead) more than Adam Smith (or John Stuart Mill). Of course, reductionism is not always apparent in this work. Grusky, Sørenson, Goldthorpe and Hope, and (in his initial point about income and other goodies) Sen are all dealing with institutional structures and processes that cannot be reduced to interpersonal relations. The question of mechanisms is essential here. Wright and Sørensen focus on different versions of micro-economic theories of exploitation (both seem to like the idea of rents, although they disagree somewhat on how rents work) that are embedded in macro perspectives on capitalism. Wright is more concerned with faithful adherence to Marxism, while Sørensen is given to flights of bourgeois fantasy (e.g., p. 226 on how competition can destroy monopoly rents), but they each derive a conceptualization of exploitation-based inequality that is clearly rooted in Marxist or Smithian (or Ricardo-based) theories of how capitalism works. Grusky is more inclined to follow the Sørensen path (Smith rather than Marx) but is more interested in defending a Durheimian theory of the division of labor as the source or social integration (and solidarity and regulation) in modern, highly differentiated societies. Thus Grusky might claim that he offers a universal theory (as some of the status attainment folk do as well) of social differentiation and inequality that should apply equally well in communist or capitalist systems. Until he reverts to his micro-economic concerns with pleasure versus utility, Sen seems to be moving away from this quest for a universal theory of inequality. Honestly, I have gained a new appreciation for Sørensen's arguments as a bourgeois attempt to reduce Marx to Smith and a renewed aversion to the rent-based theory of exploitation and to Wright's efforts to reduce inequality to exploitation. As we shall eventually learn (but not from Grusky), my inclination is to follow Tilly and distinguish between opportunity hoarding (similar to closure but not so exacting) and exploitation (similar to Wright and Sørensen but more narrow because it is not being stretched to accommodate opportunity hoarding). Here, along with Goldthorpe and most mainstream Weberians, Hogan and Tilly are inclined to allow for within class mechanisms (notably, opportunity hoarding, which covers cartels and unions) that generate and sustain inequality. Whether a society without inequality is possible is not a major concern for Tilly (or Hogan). One last observation. It is too early in the semester to miss a class meeting and too late to continue without taking stock. First, we should try to read ahead for next week. "Part IV: Inequality at the Extremes" includes three classic statements that should have been (and were, in the last edition) in the Week 4 assignment—Mosca, Mills and Giddens. The "Contemporary Statements" are all new (except for "Post Communist Managerialism" (which belongs in Part IX). "Poverty and the Underclass" is all new (except for Wilson and Massey, which were in Part VI—race and ethnicity). My inclination would be to treat Giddens, Domhoff and Ehrenreich as the successors to Mosca and Mills. The rest we can discuss when we get to race and gender (after we spend a week a mobility). Basically, this means adding these five reading to the readings from last week for discussion on Tuesday. Can we do that?