The Clinical Pathways Collaborative Initiative (CPC): Evaluation

advertisement

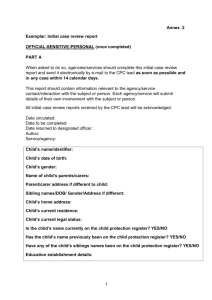

Health Services Research Centre The Clinical Pathways Collaborative Initiative (CPC): Evaluation Report For The Capital and Coast District Health Board Greg Martin, PhD December 2010 2 Table of Contents Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Background ............................................................................................................................. 6 1.2. Capital and Coast Clinical Pathways Collective Process .......................................................... 6 2. Aims............................................................................................................................................... 10 3. Study design and methodology .................................................................................................... 11 Participant recruitment..................................................................................................................... 11 4. Results ........................................................................................................................................... 12 Presentation of findings .................................................................................................................... 12 CPC group meetings .......................................................................................................................... 12 Interview data ................................................................................................................................... 12 Aims of the CPC process ................................................................................................................... 13 Development of individual CPs ......................................................................................................... 15 CP implementation ........................................................................................................................... 18 Process improvement ....................................................................................................................... 19 5. Conclusion and Recommendations............................................................................................... 24 References ............................................................................................................................................ 26 Appendix 2 ............................................................................................................................................ 29 . 3 Abbreviations A&M Accident and medical ACC Accident Compensation Corporation CCDHB Capital and Coast District Health Board CP Clinical Pathway CPC Clinical Pathway Collaborative EBM Evidence based medicine EPA European Pathways Association GP General practitioner HSRC Health services Research Centre PC Primary care PHO Primary Health Organisation SC Secondary care Acknowledgement The author thanks the participants, who gave freely of their time to contribute to this project. 4 Executive Summary In keeping with international and national developments (e.g. The European Pathways Association, the Canterbury Initiative) the Capital and Coast District Health Board (CCDHB) has begun a move toward developing integrated care across Primary and Secondary care providers. The Clinical Pathways Collaborative (CPC) was established to manage the development of Clinical Pathways to improve communication between clinicians, smooth the patient journey between primary and secondary care, maximise the efficient use of resources, and promote the best patient outcomes through the implementation of best evidence-based clinical practice. The ultimate goal being to achieve improved quality, consistent, convenient and streamlined care for patients closer to home. For the first CPC development wave, four multidisciplinary clinical networks were brought together to develop Clinical Pathways for the management four areas of healthcare identified : cancer, palliative care, gastroenterology/endoscopy, and paediatric-to-adult transition. Each of these area networks comprised a group of key stakeholders from primary, secondary and tertiary care; including physicians, nursing staff, and healthcare managers was assembled. The development process is intended to be clinician-led, to reflect the reality that cooperation between clinicians at the various levels of care is critical to the success of clinical integration and CPs. The aims of the current study were to explore the process of bringing together a multidisciplinary clinical group from across the healthcare spectrum to develop clinical pathways for specific disease or problem categories. It documents the barriers and facilitators to effective development of CPs and integration across levels of healthcare, and draws on the experiences of participants to determine how these processes could be improved. We conducted a qualitative, process evaluation. The opinions and experiences of key stakeholders (i.e. representatives from primary, secondary and tertiary care, health service managers) on the clinical pathway development process were canvassed by semi-structured interview. There was a general consensus reported by participants was that it was good to get representatives of primary and secondary care in the same room, and talking face to face. Comments reflecting this were made by all, including those participants most sceptical of the process, and those who judged the current process to have been of limited success in achieving its change goals. The process is seen to have potential to improve clinician understanding and communication, improve patient management, and increase efficiency. A number of less successful aspects of the current process were identified and suggestions for improvements provided. These are documented in the report in the form of direct quotes from those involved. Principal among the suggested improvements for future CPC projects was clearer problem definition at the outset; there needed to be more specific aims that were to be achieved. The topic areas to be addressed needed to be clearer and measurable. It was also suggested that there should be greater transparency; participants should be fully informed of the goals of the project prior to participation, including the resource constraints. Logistical and organisational improvements (e.g. set meeting times; encouraging consistent attendance by participants) were also suggested. It was suggested that future groups formulate the questions very early on so they have a very clear idea of what they are trying to improve and how they are going to measure that improvement. 5 1. Introduction 1.1. Background Integrated Care (or Clinical Integration) has become a widespread goal across health systems and countries in response to the common challenges of the 21st century: an ageing society, long term conditions and multiple morbidity (Chan & Webster, 2010; Bower, 2009; Ryall, 2007), and as a result of concerns over fragmented care arising from the multiple organisations and professional groups involved in delivering health care services. Numerous projects and a great variety of models have been developed over recent years to overcome systemic, professional, organisational and cultural barriers in order to smooth out patient clinical pathways and information flow and ensure equitable provision of high quality, clinically effective services (Vanhaecht, et al., 2006; Rotter et al., 2007). Of course this does not come without frictions, and even when integration projects have proven to be successful, obstacles remain to be solved, such as managing the change and sustaining innovations. 1.2. Capital and Coast Clinical Pathways Collective Process In keeping with international and national developments (eg. The European Pathways Association, the Canterbury Initiative) at the Capital and Coast District Health Board (CCDHB), and its partner organisations, there is an emerging move toward developing integrated care across Primary and Secondary care providers. This is not just to look at clinical care pathways but also the priorities for change; collaborative ways of working; value for money; health worker development; and most importantly improved quality, consistent, convenient and streamlined care for patients closer to home. For CCDHB and its partners, clinical integration is: A descriptive term for primary care physicians, specialists and hospitals working together to care for the patient; A clinician-led program and A system to measurably improve patient care. The clinical integration project at CCDHB focuses on better defining clinical pathways through collaboration of clinicians across the healthcare spectrum. These pathways in turn aim to reduce needless referrals and hospital visits by ensuring ready access to diagnostic and specialist support in primary care and community settings. The development of clinical pathways in the promotion of evidence based medicine and equity of access to health services is now well supported in the literature (Panella et al., 2003; Rotter et al., 2007; Gray, 2008; 2009). Clinical pathways (CPs) are multidisciplinary care plans that outline the sequence and timing of actions that are necessary for achieving expected patient outcomes and organisational goals regarding quality, costs, patient satisfaction, and efficiency (El Baz et al., 2007). CPs provide specific guidelines for care that describe treatment goals and define a sequence and timing for meeting those goals efficiently. 6 According to continuous quality improvement principles, CPs stress the improvement of clinical processes in order to improve clinical effectiveness and efficiency. Thus, CPs are clinical management tools used by health care workers to define the best process in their organisation, using the best procedures and timing, to treat patients with specific diagnoses or conditions according to evidence based medicine. As a consequence, the introduction of CPs could be an effective strategy for health care organizations to reduce or at least to control their clinical performance variations (Panella et al., 2003). In keeping with the policy direction of the NZ Government’s “Better, Sooner, More Convenient” discussion paper (Ryall, 2007), CCDHB for the first wave, brought together four multidisciplinary clinical networks (the Clinical Pathways Collaborative) to develop CPs for the management of each of the four areas of healthcare identified : cancer, palliative care, gastroenterology/endoscopy, and paediatric-to-adult transition. These four initial work-stream areas were endorsed by the Primary Secondary Clinical Governance Group; the oversight body which was established in February 2008 (with revised terms of reference in September 2009) to oversee the development of clinical integration. The purpose of this group was described as: “The Primary/secondary Clinical Governance Group will ensure patient outcomes are maximised by improving quality and reducing risk across the patient journey though Primary/Secondary/Tertiary systems” It was noted that the clinical Pathway collaborative would: “feed information to this group for support, agreement to move forward, funding issues and evaluation of change purposes” A number of specialities expressed interest in being involved in CPC development for issues including gastroenterology, opthamology, dermatology, heart failure, paediatric surgery, palliative care, breast cancer diagnosis, discharge planning, neurology, general surgery, cancer (bowel and lung pathways) and respiratory. To enable a transparent process for the identifying the four initial CPC work-streams areas to pursue, the Primary Secondary Clinical Governance Group used a set of evaluation criteria to identify the most appropriate candidates. These criteria included: clinical risk, sub-optimal clinical performance, willingness to participate, funding available, limited cost implications (if known), measureable outcomes, and fit to C&C DHB plan. As noted above the areas identified were cancer, palliative care, gastroenterology/endoscopy, and paediatric-to-adult transition. For each of these area networks comprised a group of key stakeholders from primary, secondary and tertiary care; including physicians, nursing staff, and healthcare managers was assembled. The development process is clinician-led, to reflect the reality that cooperation between clinicians at the various levels of care is critical to the success of clinical integration and CPs. 7 The CCDHB process involves process involves: A timed structured programme of 6 meetings over 15 weeks leading to an implementation plan for 3-4 key priorities for action (see Figure 1 for a schematic). The first two meetings will be with clinicians from Primary and Secondary care to discuss issues, challenges, and opportunities for improving the patient pathway for a specific area by improved collaboration and cooperation. This will aid better understanding or roles, respect for peers issues and develop key relationships. Subsequent meetings with clinicians will include other stakeholders who will be involved with the service to determine pathway details Production of a priority list for improvements and an implementation plan to establish the new integrated pathway A governance structure that includes oversight by the Primary/Secondary Clinical Governance Group, which provides a reporting line for the Clinical Pathways Collaborative The four Clinical Pathways Collaborative projects represent an initial phase in clinical integration and CP development at CCDHB. If this proves successful, further clinical integration and CP development projects are likely in other areas of healthcare, e.g. respiratory, heart failure, breast cancer, ophthalmology. A process evaluation of the initial four projects, as set out here, will provide valuable data to inform the future development of other clinical integration and CP projects. The CPC Initiative proposal to initiate the CPC process (dated September 2009) sets out a governance framework, a structure for prioritising work-streams, a process to identify clinicians to participate in the work groups, a structure and timeframe for the series of meetings themselves, and it emphasizes the need for measurement and evaluation of outcomes to determine progress. In addition it identifies a number of areas of risk associated with the process and some potential mitigation of those risks. These risk and mitigation are summarised in Table 2 Table 1 Risk Financial risk due to: Will need new monies Service should move across sectors but funds cannot follow Contractual arrangements difficult and need unbundling. Lack of participation, unwillingness to participate. Insufficient representation from either side. Mitigation Expectations of new monies must not be raised. Information on budgets to discuss reinvestment should be available. Include finance/ contract personnel in discussions as early as required. Ensure information is shared re context; process; outcomes and governance, along with support from Executive level. Arrange and provide facilities at a mutually convenient time with refreshments and timeframes. 8 Cultural and poor inter-relationships between professionals. Lack of information on specific aspects of service/pathway. Pathway development covers sub regional areas. National and regional bodies developing alternative pathways No demonstrable or measurable improvement in patient pathways Lack of implementation Obtain accreditation sign off for CME points for Clinicians and certificates of attendance for other Health professionals. Follow process with timelines. Ensure all participants have time to speak and all opinions are respected and valued. Provide access and availability of data and information if requested. Ensure participation from clinical body for all involved areas. Provide alternative governance from other existing forum’s for overseeing if appropriate. Clinical advisors maintain relationships with national processes under development. Strong facilitation. Careful prioritisation to ensure linkages to priorities and funding availability. Clear implementation plans developed as part of process The extent to which these risks were apparent and/or effectively managed in the four work-streams will be considered in relation to the interview data and the outcomes of the group processes. The intent of this project is to provide the CCDHB with policy and clinically relevant information on the processes involved in the development of CPs, the benefits of CPs being developed in this way, and the challenges faced in the development phase, and to contribute to the refinement and continuous improvement of the pathways so developed. The project also provides information about the overall challenges faced in aiming to better integrate care across existing services and providers. 9 2. Aims The aims of the study were to explore the process of bringing together a multidisciplinary clinical group from across the healthcare spectrum to develop clinical pathways for specific disease or problem categories. It documents the barriers and facilitators to effective development of CPs and integration across levels of healthcare, and draws on the experiences of participants to determine how these processes could be improved. The results of the study are intended to directly aid the CCDHB in further development of additional clinical pathways and integration projects, in addition to improving services through the coordinated implementation of evidence based practice. Our key research questions were: What are the strengths and weaknesses of the governance and clinical network arrangements being developed by CCDHB and its partner organisations, in relation to the overall aims of improving integration of services? What issues (barriers and facilitators) are there in relation to integrating services in the four clinical areas where networks have so far been established? What implications do these issues have for future integration? What lessons can be learned from the initial CPC development streams and how can this contribute to an improved process and implementation of future CPC efforts? The ultimate aim of the study is to contribute to development more effective health service delivery across and between all levels of health care for specific areas of need through examination of the development process of clinical networks and clinical pathways. It will provide quality evidence to decision makers and clinicians regarding the development of networks with the aim of improving integration of services. This will explicitly aid in the translation of knowledge into “best practice” as evidence-based clinical pathways are developed which will maximise outcomes by improving quality, increasing efficiency, and reducing risk across the patient journey through Primary/Secondary systems. The contribution of the study is to support the development of efficient systems that will contribute to improved healthcare and improve equity of access to health services through a reduction in practice variation, and the promotion of collaborative clinical pathways. 10 3. Study design and methodology We conducted a qualitative, process evaluation. This qualitative method is appropriate for exploring and understanding different people’s perceptions and experiences of the clinical collaborations (Cresswell, 2009) and it involves an assessment of the processes involved in the clinical collaborations and how well these collaborations are seen to be likely to achieve the key goals set down for them. The research involved two key methods – document review and key informant interviews. Key documents examined included the terms of reference for the collaborations and minutes from the governance groups and collaborative network meetings. The opinions and experiences of key stakeholders (i.e. representatives from primary, secondary and tertiary care, health service managers) on the clinical pathway development process were canvassed by semi-structured interview (the interview schedule is attached as Appendix 1). All interviews were recorded and transcribed for further analysis. Some quantitative data was collected in the form of Likert scale assessment of key questions (e.g. overall satisfaction with the process, perceived usefulness of the Care Pathway developed; extent to which the process was collaborative rather than “top down”). Both documents and key informant interview transcripts were analysed using thematic techniques, using the research and interview questions to guide the analysis, as well as identifying new themes inductively from the data itself. The research documented key activities involved with the collaborative networks, and analyse the findings from the document analysis and interviews to identify the strengths and weaknesses, and ways of improving, clinical network processes at CCDHB. It will also identify any key issues that arise in relation to the aim of increasing integration of services across providers. Participant recruitment A list of work group participants and their contact details was provided by staff from CCDHB Planning and Funding. Recruitment efforts were conducted in such a way as to ensure a mix of representatives from the primary and secondary care, and senior health service managers. Potential participants were approached, initially by email, and subsequently by telephone. Up to four attempts were made to establish contact with each individual before they were considered non-responders. Of the 25 potential participants contacted, four declined to be involved, one had left the country, and five were unable to be contacted or did not respond, leaving 15 participants who completed interviews. 11 4. Results Presentation of findings The presentation of findings will be broadly structured as per the interview schedule. The questions will be briefly restated and, where possible, a summary of the central theme of the responses will be provided in addition to a selection of verbatim answers to illustrate the responses. In some cases there is a degree of thematic unity around the responses received. In many other cases, however, there was a broad diversity of opinion and as such responses will be reported to reflect this diversity. In certain cases, questions were skipped due to many respondents being unable to provide an answer; this will be noted, as appropriate. It should be noted that the four CPC groups reported on here addressed very different CP issues and this is reflected (and noted) among the responses. Where appropriate it will also be noted whether the participant is a representative of primary health care (PC), secondary health care (SC) or health management (HM). CPC group meetings The background document describing the CPC meeting process which was presented to the Primary and Secondary Clinical Governance Group (September 2009; included as Appendix 2) recommended a series of six CPC group meetings over a period of some 16 weeks. Despite an ostensibly similar CPC development process, it was clear that the groups progressed differently. The Cancer group met three times in total while the Palliative Care group met up to seven times (plus some additional “offline” sub-group meetings). The relatively low number of meetings held by the cancer group was in part due to delayed starting and logistical issues within the hospital oncology department, rather than a lack of will. Interview data Prior to addressing specific questions and themes it is worth noting that a universal theme reported by participants was that it was good to get representatives of primary and secondary care in the same room. Comments reflecting this were made by all, including those participants most sceptical of the process, and those who judged the current process to have been of very limited success. “The great thing is that it does get both primary and secondary together, and talking. And I think that’s really useful. It’s nice to see people face-to-face, actually, rather than just email all the time. It provides a good forum...for everybody to put their ideas on the table and 12 discuss them. There’s a lot from the hospital point of view that we don’t understand in general practice....and I think that there is a lot they don’t understand” (PC) “It was good that representatives of primary and secondary care got together in the same room. There was no bad vibe between primary and secondary doctors”. (PC) “meeting the GPs was good – we don’t usually get to meet them; it was good to meet a motivated group of GPs” (SC) “getting people together was good – to get a sense of what the issues are. It was mandated by the CEO and Board so it had high level support” (SC) “I think having the clinicians both primary and secondary get together in the first instance to talk about what the issues are, what the outcomes are looking for and therefore what some of the solutions might be is really good. Because you usually find then that they have quite a frank, open discussion without worrying about funding and all those things that get in the way. And then bringing in the operational management side and the funding side a bit further into the process is good” (HM) Aims of the CPC process What do you understand to be the background to the CPC? Most participants had some comment on the background of the CPC, though the understanding of the background and aims of the group varied widely. Some expected specific issues to be addressed while a number of others were unaware of or unclear about the group aims. Most had only a vague or general notion of the aims of the CPC process. “For us it was very specific, they were looking at the interrelationship between primary and secondary care but within that, through Gastro, there were already some identified issues. So it wasn’t a nebulous start, you had a very definite start with, what can you do about referral numbers? Are there ways we can reduce the number of referrals?” “I didn’t really know why we were there and who had called this together. Was it the DHB or was the Gastroenterology clinic, or was it GPs, and what was the aims of it............I got the feeling early on that there were people sitting around this table that don’t want to be here” 13 “I understood it was to foster some understanding between primary and secondary care to see how we could move forward, I guess, in giving patients the best treatment, but also perhaps also taking some of the burden off secondary care....moving it a bit more into primary care. And also i think it was an opportunity to have a bit of a discussion and perhaps forge a few links” (PC) “As much as possible between primary and secondary care...in agreeing on what the evidence based pathway is and getting to a common set of principles or actions that would occur prior to each step to actually make the continuum better for the patient but also the most efficient use of resource.” “...it was about facilitating interaction between primary and secondary clinicians” “no idea....I was invited to join” What were your expectations of the CPC? Expectations of the process were mixed, with some scepticism but also considerable evidence of good will. “I don’t think I had any” “..to me, that’s how I perceived it....looking for efficiencies. Can we achieve the same outcomes in different ways” “expectations were minimal due to being involved in other projects within the DHB that become a talking shop and go nowhere....resigned to ‘here we go on anther process’. And what is that is going to be different with this process? When we look back in two years and see that nothing has changed. People left...senior management leave...there isn’t funding...the politics remains the same” “I certainly had expectations that <we> would come up with some ideas that we would be able to implement and that it would better define what could be done in primary versus what we’re doing currently, in secondary” “My expectation was...I imagined there must be some issue with access to gastro stuff, or their ability to provide a service....and we were trying to work out a way of streamlining or improving that...but I didn’t know what the problems were, what GPs were saying to the gastro clinics about where the shortfalls were, what gastroenterology was wanting to get from GPs, or whether this was driven by the DHB. I suspected it was about saving money......” 14 Development of individual CPs Was the CPC process clear? As noted above there were differing opinions on the clarity of the expected process. Was the process clear? “Yes” “Not particularly, I have to say. You get on to these committees – somebody says ‘you’ll be alright, you have some spare time, why don’t you do it’.....I’m not sure we’re always the best representatives, if you know what I mean” “I obviously knew it was about oncology; I was a bit hazy on everything else...it was sort of to increase liaison between primary and secondary and see how things could be improved..” “I don’t think the specific goals......you can talk about “we need to improve communication”......you can say “we want to improve patient outcomes” , but what do you want to improve by? What is the issue? It’s all very jargonised and cliché: outcomes and measurable and so on, whatever the current words are. Is it about improving cure rates, is it about patients being happier, is it the community being happier about what is going on. What is it that you want to improve. And some things might not need to improve; I certainly got the feeling in the Cancer one that a lot of things are working”. What were the good and less good things about the CP development process? Good things: As noted above, the most commonly cited “good thing” about the CPC development process was getting people in to the same room to allow a face to face dialogue, exploration of the issues, and an understanding of each other’s perspective. This was by far the most commonly cited “good thing” about the process. “Getting to meet some of the Gastroenterolgists face to face - that was good” “...we had the clinicians from the DHB and then we had primary care and they all came in willing with a positive attitude that we can achieve something. So yeah that was good…. There seemed to be administrative support of what’s happening and that doesn’t often happen in the DHB and that’s how a lot of things fall over, they say let’s do this, then you turn up and you realise that you’ve got to do everything. Yeah so they seemed to have the time and funding to do it.” “Fostering any sort of closer relationship is positive” “There was an underlying ethos of trying to do the best for the patient..” 15 Looking to see how you can do something better is always a good thing..” “The potential to streamline referrals.....I would like to see some clear guidelines around referral for gastroscopy.....we don’t want to make inappropriate referrals but it helps if we are given guidelines as to what is an appropriate referral” Less good things A common theme of the “less good “aspect revolved around the difficultly of having the same people attend consistently. This led to the revisiting of issues covered in previous meeting and the need to spend time getting people up to date. “The group...there was a core who might be present at most meetings.....but....a fairly essential person was only present at one....people were present for some meeting but not for others.....I think that was a real failing, it was difficult to get these busy people, as a group, together at one time” “To be truly effective you needed the same people to be present so you weren’t reinventing the wheel – going over old ground...relitigating what had been discussed at previous meetings” “The only thing that did vaguely irk me...was that...the meeting nights were changed.....so that wasn’t very well organised....expectations...you should have some sort of document that about what the expectations are: how many meetings you are going to go to, what days they are, what times they are, and stick to that..” “I think it could have been organised slightly better.....and it would have been nice to have a final meeting...it just sort of finished...I didn’t feel it was completed” “we couldn’t get the same group of people together consistently.....so I thought that did undermine the veracity of it” “Just the stickability of the clinicians was poor, myself included. I tried…Also I think just the size of the task. It sounds very simple, do this but actually to do it properly it is actually quite an involved task. Having to turn a juggernaut around or develop new systems or having people work a different way… it’s huge. Maybe bite size pieces would have been better.” “One criticism I would have, or one short fall, is how are we going to measure whether we’ve done anything? Good, bad and different.” “We didn't pick narrow enough areas we could deliver on”. “I got the impression that a lot of this was about improving the cancer patient ‘journey’. Making it better for the patients. But what do the patients want? Nobody ever asks the patients. It‘s all very well to say make it better but why not ask the patients?’ “It felt ad hoc” 16 <In relation to an earlier report on the Primary/Secondary interface> “In the report he wrote about 3 years ago were the things that we were talking about in this session........it was like no-one had read it, or picked up the ball and run with it, or taken any notice of it. It was extraordinary. So I thought to myself... if someone had taken the time to follow through with the recommendations, we may not have needed to meet” Was the CP developed based on evidence and local consensus? There was broad agreement that discussions were based on evidence and broad consensus, even when this did not translate into new CPC protocols. For most groups there was no successful completion and documentation of a CP protocol . A successful example was the FODMAP diet advice and training that emerged from the Gastroenerology group, along with guidelines on CT Colonoscopy which are being developed and will be distributed to GPs. “A new diet, the FODMAP diet, was discussed and an education session was conducted for GPs” “The FODMAP diet was based on the evidence that in diagnosed patients with irritable bowel syndrome forty percent would improve so we used that as basis for our recommendation okay if the GP is confident about diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome immediately start the diet and see what happens and see if that has an effect on our referral process and see if it has an effect on patient management for GP perspective. The CTC is based on best practice”. Other groups were less successful in developing CPs, although after-hours medication availability was successfully addressed in the Palliative Care group. Was the process collegial or imposed top-down? (Were all voices listened to?) “I think it was sort of collegial.....the discussions around the table were collegial...we (GPs) certainly respect the knowledge of our specialist colleagues.....I think it comes back to this business of why we were there and did people want to be there...” “The tone of the meetings was very collegial...it was refreshing..” “Yes, all voices were listened to” How effective was the workgroup facilitation? Some groups found the facilitation to be excellent where others were less satisfied. This seemed to differ across groups, with the members having differing opinions. “From the meetings I attended I thought it was very good, ongoing follow up, emailing updates and new information… that was what I was alluding to before that it seemed to 17 have the right back up which was a bit of a surprise… We might be talking about something and say look is there an article that can help us out here, is there some data that we need and that would be circulated in the group.” “I think it was poorly facilitated” “The facilitation was irritating.... drove it in a preconceived direction...and in the wrong direction” “The facilitator was excellent. Her style of engaging with people and her ability to bring people together who may not have known each other very well, particularly primary and secondary medical clinician” “..the woman who facilitated it; she had a really difficult job and she actually did quite well. She was good at trying to sum up what had been done, and sending out the mails....keeping people in the loop, trying to keep the meetings on track, identifying the areas we thought we’d look at and trying to get some outcomes in those areas...... but it was all a bit ‘waffly”’ really, I mean, the whole thing was a bit ‘waffly” Is the CP documentation clear? Do you have a written CP protocol? How could it be improved? No written CP protocols were available at the time of interview. What monitoring and evaluation of variances from the pathway is included in the CP? (e.g. timeframes, availability of appropriate medications)?? Who is responsible for variance analysis/detection and response? No variance analysis was built in to the pathways as they were at an early stage of development, and do not necessarily lend themselves to that model CP implementation The initial design of the evaluation included consideration of the issues surrounding the implementation of the CP projects developed in the earlier phase, to see what could be learned for future implementation processes. At the time of evaluation, however, no CPC had begun implementation, although the Gastroentetrology group was in the process beginning to do so with the FODMAP diet and the CT Colonoscopy guideline. Other CPCs were either still in development or were on hold following staff changes. 18 Process improvement What should future CPC development projects do differently? Participants had a broad range of suggestion for how to improve the CPC process; these focussed on clarity of purpose, definition of aims and goals, and choosing appropriate specific, measurable and achievable goals. Many of the participants recommended that the people involved in the development of CPC projects have a much clearer idea of the content of the discussions before the first meeting: “Before it started I’d like to know, first, whose idea it was, what the perceived problem was, and what the aims of the group were. So, in this case it might have been useful to know, for example, that P&F had called for this group, maybe that it was thought that there were too many inappropriate referrals, or maybe they thought that the waiting times were too long, or maybe they were wanting to save money and we were potentials for savings...and how is this going to impact on general practice and how is this going to impact on the gastroenterology clinic.” (PC) “I think that people...before they came to the meeting should actually have garnered some ideas or identified areas that could be improved on so we came to the meeting having already identified a number of areas, and we thought that those identified would probably be similar to what our colleagues identified – so that we could use our time more efficiently”.....(SC) “Maybe formulate the questions very early on so you have a very clear idea of what you are trying to improve and how you are going to measure that improvement.” (SC) “Before it started... I would have liked to have got something in writing to look at before it started.” (PC) “Having background material to read prior to meetings would be god...to feel prepared.” (PC) “I think it might have been better if, as GPs going in to it, we had more of a feel of what our colleagues wanted....I talked a little bit to my peer review group but that was really after the process had started. If we are representing general practice it would have been be nice to have some more generalised views. So I suppose I felt a bit under-prepared.” (PC) As documented above many participants commented on the need to have stable groups and regular participation. 19 The first meeting was highlighted as being of particular importance by some of the interviewees as a time to define the scope and direction and provide a framework upon which other meetings are based: “At the start there should be a sort of definitional exercise; maybe, from a general practice point of view, what are your issues?.... from a gastroenterology point of view what are your issues?... from a Planning and Funding point of view, what are your issues? Then everyone has put it out there and weca look at how we can go about solving some of these.” (PC) “The first meeting and the last meeting is really important. At the first meeting you have to set the agenda, say why you are there and what everybody’s expectation are....” (PC) “First meeting should give a framework for the rest of the meetings and formulate some ideas that you can then add on in the next meetings...” (PC) “The initial findings of areas of interest should be identified by clinicians....otherwise be up front and say the purpose of the meeting is to save us money, which was never said as being involved. It was not set up as a goal....if it is not transparent what the process is then we can’t really engage” A related issue that emerged very strongly was the requirement to have clear and appropriate goals set out about what is being attempted to be achieved. This is where the participants showed the clearest unity in their opinions. “Clinical pathway means something different to me...I didn’t really feel that the patients pathways was clarified...what do you do here and what do you do there...how can we speed up the process. It was a lot more of a morass, it went around and around” (SC) “They needed to have much more specific goals that they wanted to achieve...they need to know what they are evaluating. You have to be measure it.” (PC) “There need to be clear parameters about the what it is the needs to be sorted. Is it a clinical question that needs to be answered; or is it a process that you want to change, alter or improve; or is it just a discussion to get an opinion.” (PC) “You need to be a lot more specific about the questions being asked of the people in the group.” (PC) “Clear objectives” (PC) They need to have much more specific goals that they wanted to achieve...they need to know what they are evaluating. You have to be measure it (PC) “I think it would be easier if there was one clear problem to be addressed” (PC) “Membership correct to begin with and they need to be clear on the parameters – everyone needs to understand the parameters. What's the resources available?” 20 “Better pick on what topics … we're going to develop them (CPs) for.” (HM) “What we've actually picked for CPC were areas – we should have done that instead of dumping it to the group because what we had when we dumped it to the group was just too many personal interests on that – it needed to be pushed above that”. (HM) This the implications for future CPC project related to this issue is perhaps best described by this participant: “I think in the future, from my perspective, it would be really good ... get together a group, maybe manager and clinicians and people who are interested and say" 'what is the problem here? and which part of this process to we want to put through a CPC process? and what outcome are we looking to achieve, really?" ... If we know and truly understand what the problem is then there might be 6 or 7 pieces of work are needed to find a solution to that problem, and maybe you can't do all 6 of them or maybe there are 2 or maybe there is just one there that might help solve all the other problems or issues - or in fact maybe the problem definition is too broad anyway, and maybe there is a very specific component of that greater problem definition that we want to put through that process to get to an outcome....We need to define the problems much better. Other comment s also relate to this issue: “Membership correct to begin with and they need to be clear on the parameters – everyone needs to understand the parameters. What's the resources available?” “Set up evaluation before and after – really clear. What's the point of doing something if you don't know if it worked?” “I don't believe the pediatric → adult is really a CPC – can't do an algorithm”. “We went for quite a consensus way of what we're going to do a CPC on – I would have picked a much narrower range of things... I'd be picking a disease and condition and how you'd manage that. But then I have a 2 fold bias – I run a hospital, and that's what I saw as worked before coming here”. The need for general transparency of the agenda, particularly as this related to resourcing was mentioned by a number of participants. This may have been relieved if clearer description of the overall process (as outlined in the Primary secondary Clinical Governance Group documents) had been provided. “The initial findings of areas of interest should be identified by clinicians....otherwise be up front and say the purpose of the meeting is to save us money, which was never said as being involved. It was not set up as a goal....if it is not transparent what the process is then we can’t really engage” (SC) “The process needs to be made more transparent...with the cards on the table” (SC) 21 “The reality is that you need to know what the financial constraints are......I’m a pragmatist” (PC) “If it is a budget, then you need to know, where is the most money being spent, where within the budget are you able to chop. The financial agenda should be clear; I think we are all aware that there isn’t a bottomless pit of money.” (PC) “If me to tell you about how to cut the budget, say so; don’t tell me it’s about communication or patient satisfaction.” (PC) “I’d be more inclined if it wasn’t coming from planning and funding; so it wasn’t something that was “lets save money”, if there was an obvious problem that clinicians had identified and they were wanting help from GPs to come to a solution; then i think they would have been more interested in finding outcomes.” (PC) “Probably in the future we would really benefit from describing, in a big picture way, what it is we're trying to do and that's all about linking all of this to a strategy of sorts ... you present that bigger picture in a summary to people you've been invited to come to the party and they're much clearer about what their role is...” (HM) “We could have provided more executive leadership..”. (HM) General Additional Comments about Primary/Secondary Communication There was considerable discussion from the GPs about computer systems and the possibility of them being used to a much greater extent to improve communication and collaboration between primary and secondary care “one of the recommendations that should come out of our meeting is that attention should be given to their <the hospital> IT system(s)..” “There was a discussion about the new pathway that will happen when all the IT systems are up and running and that there will be far more electronic communication...and you wonder, maybe they should address that first..and then see how that could be manage. They are going to an electronic system between GPs and the hospital and back...that will change the nature of how we do things....” . 22 23 5. Conclusion and Recommendations There was a general consensus reported by participants was that it was good to get representatives of primary and secondary care in the same room, and talking face to face. Comments reflecting this were made by all, including those participants most sceptical of the process, and those who judged the current process to have been of limited success in achieving its change goals. The process is seen to have potential to improve clinician understanding and communication, improve patient management, and increase efficiency. The C&CDHB CPC process, as outlined in the document submitted to the Primary Secondary Clinical Governance group is clear and based on other national and international best practice CPC development processes. It seems that in this initial series of CPC developments, the development phase did not follow the specified process as closely or successfully as it might have optimally. Valuable lessons can be learned for how the first CPC processes evolved. The interview data reveal key themes and lessons that could be applied to future CPC developments. The first is that in the clinical participants’ eyes, there should be a clear purpose and a well understood rationale for being involved in the CPC process that is clearly and fully communicated to them prior to the beginning of the process. According to some participants, they were unclear as to the aims and goals of the CPC and it parameters. Future CPC developments should ensure that all participants are fully informed of the rationale and aims of the process, in detail and preferably in writing, to remove any misunderstanding of the motivations of the process. The resource implications (i.e. financial boundaries) of the process should also be made clear to participants from the outset. The need for transparency of process was a common theme in this project. This could be assisted by careful choice of participants and ensuring that groups are not brought together ad hoc, without sufficient information about what they will involve. Written invitation to participate, with full project description, may be preferable to , for example, a brief telephone invitation. The appropriate choice of members of a group was also discussed by some participants and recognised as a potential risk by C&CDHB planning documents. In particular a common theme of the “less good “aspects revealed in this project revolved around the difficultly of having the same people attend meetings consistently. This led to the revisiting of issues covered in previous meetings and the need to spend time getting people up to date. While this is to some extent unavoidable, future groups should attempt to obtain a reasonable level of commitment from participants to maintain their involvement, and set a firm timetable. The principal lesson to emerge from this study is that future CPCs would benefit from including a clearer, more specific problem definition; work areas that can be defined, operationalised and measured. While there still exists considerable debate in the literature about the nature of “clinical pathways” (Vanhaecht et al., 2006; Gray, 2009), it is clear that being able to define them at a functional and operational level is key. The most common concerns with the C&CDHB CPC process was the lack of clear problem definition. The notion of “improving paediatric to adult transition”, for example, is a type of “meta goal” that can be conceived of as consisting of smaller more clearly defined aspects which can be pursued individually. The Christchurch Initiative has produced a 24 significant number of pathways for various clinical areas; it may be that the approach they have taken – very tightly defined problems areas and responses – is the way to make incremental progress toward the larger strategic goals of improving patient outcomes and maximising the efficiency of resource use in both primary and secondary care. 25 References Bower, K.A. (2009). Clinical pathways: 12 lessons learned over 25 years of experience. International Journal of Care Pathways,13, 78–81. Chan R,Webster J. End-of-life care pathways for improving outcomes in caring for the dying. CochraneDatabase of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD008006. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008006.pub2. Creswell, J.W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed models approaches (3rd Ed). Los Angeles: Sage. Cropper, S., Hopper, A. & Spencer, S.A. (2002). Managed clinical networks. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 87, 1-4. El Baz, N., Middle, B., van Dijk, J., Oosterhorf, A., Boonstra, P. & Reijneveld, S. (2007). Are the outcomes of clinical pathways evidence-based? A critical appraisal of clinical pathway evaluation research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 13, 920–929 Feuth, S. & Claes, L. (2008). Introducing clinical pathways as a strategy for improving care. Gray, J. (2009). The future of care pathways and their journal. Journal of Integrated Care Pathways, 12, 5660. Gray, J. (2008). It’s not what you do, it’s the way that you do it. Journal of Integrated Care Pathways, 12, 43-44. Gray, J. (2009). The future of care pathways and their journal. International Journal of Care Pathways, 13, 1-6. Panella, M. (2009). The impact of pathways: a significant decrease in mortality. International Journal of Care Pathways, 13, 57-61. Panella, M., Marchisio, S. & Di Stanislau, F. (2003). Reducing clinical variations with clinical pathways: do pathways work? International Journal for Quality in Health Care,15, 509-521. Rotter, T., Koch, R., Kugler, J., Kinsman, L., & James, E. (2007). Clinical pathways:effects on professional practice, patient outcomes, length of stay and hospital costs. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3, CD006632. Ryall, T. (2007). Better, sooner, more convenient: Health discussion paper. Wellington: Office of the Leader of the Opposition. Vanhaecht, K., Bollmann, M., Bower, K., Gallagher, C., Gardini, A., Guezo, J., Jansen, U., Massoud, R., Moody, K., Sermeus, W., Van Zelm, R., Whittle, C., Yazbeck, A.M., Zander, K. & Panella M. (2006). Prevalence and use of clinical pathways in 23 countries-an international survey by the European Pathway Association. Journal of Integrated Care Pathways, 10, 28-34. 26 Vanhaecht, K., De Witte, K. & Sermeus, W. (2007). The care process organization triangle: a framework to better understand how clinical pathways work. Journal of Integrated Care Pathways, 11, 54-61. Verkerk-Geelhoed, J. & Van Zelm, R. (2010). What competencies are needed by operational managers in managing care pathways? International Journal of Care Pathways, 14, 15-22. 27 Appendix 1 WEEK CLINICAL PATHWAY COLLABORATIVE Step 1: Gather information from service providers/clinicians and identify wave 1 Use clear transparent process to identify first wave participants 5 Step 2: Meeting 1 Primary and Secondary Care Clinicians Presentation on background/context free to discuss issues: challenges: concerns 7 Step 3: Meeting 2 Relevant Key Stakeholders and Clinicians Continue discussion from above and priority list for improvement described 9 Step 4: Meeting 3 Relevant Key Stakeholders and Clinicians Clinicians present issues/priorities and open discussion. Review priority list and requirements for change 11 Step 5: Meeting 4 Relevant Key Stakeholders and Clinicians Repeat above and discuss. Finalise priorities list with plans to implement change including identifying any resources required 13 Step 6: Meeting 5 Relevant Key Stakeholders and Clinicians Finalise implementation plan with key responsible roles agree output measures 1-3 19 Step 7: Meeting 6 ALL Evaluate and Impact Analyse Outcomes Present to Primary and Secondary Clinical Governance Group Present to Primary and Secondary Clinical Governance Group Appendix 2 August 2010 Clinical Pathways Collaborative Evaluation Project Clinician/Stakeholder Interview The following guide provides an outline of the topics that will be covered. The questions are indicative of the subject matter and are not verbatim descriptors of the interviewer’s questions. Introduction Explanations of the use of the evaluation data Comments Report to C&CDHB Appreciation of contribution Confidentiality and procedure of the interview [including the use of audio equipment] Confirmation of the duration of the session Establish parameters 0.5 to 1 hour Thank you for agreeing to be interviewed as part of the Clinical Pathways Collaborative Evaluation. The purpose of the interview is to examine how individual practitioners and other stakeholders feel about the development of the CPC projects, how it is affecting your practice, and how future CPC projects could be improved. CONSENT FORM I agree to be interviewed for this research project by one or two members of the Research Team. I agree to the tape-recording of the interview, understanding that the tapes will be heard only by the research team. I understand that the discussions will be coded and identifying information will be removed. I understand that I may withdraw information from the Project at any time. Signed:_________________________________________ Name:__________________________________________ Date: _______________________ Please note: The Wellington Regional Ethics Committee has agreed that this research does not require formal ethics approval. A copy of their letter is available on request. 30 1.3. 1. Participant’s role in the CPC structure and process Which CP are you involved with? Palliative care/Cancer/GI-endoscopy/Paedeatric to adult transition? Your role: Clinician? Primary/secondary? Clinical team leader? Health manger? Were you involved as a member of the Primary Secondary Clinical Governance Group? How many workgroup meetings did you attend? How useful were they? 1.4. 2. Aims of the CPC process What do you understand to be the background to the CPC? What were your expectations of the CPC? 1.5. 3. Development of individual CPs How satisfied were you with the CP development process? Was the process clear? What were the good and less good things about the CP development process? Was the CP developed based on evidence and local consensus? What barriers, if any, were there to the CP development process? Was the process collegial or imposed top-down? (Were all voices listened to?) How effective was the workgroup facilitation? In your opinion does the CP clearly specify the desired goals and outcomes for patients and the care activities needed to achieve these goals? How do you feel about the recommendations? Is the CP documentation clear? Do you have a written CP protocol? How could it be improved? What monitoring and evaluation of variances from the pathway is included in the CP? (e.g. timeframes, availability of appropriate medications)?? 31 Who is responsible for variance analysis/detection and response? 1.6. 4.CP implementation How are the new CP processes working? If the CP(s) have not been implemented, why not? What are the characteristics of the CP that have been most useful and those that have been least useful? What were the implications of the new CP for service delivery and for your practice? What barriers/difficulties were there in implementing the CP? In what way and to what extent have patient outcomes been (or will be) improved by the CP? How would we know? How important it is to formally evaluate the outcomes from the individual CPs. 1.7. 5. Process improvement What should future CP development projects do differently? How could the process of CP development have been improved? How could the implementation of the CP been improved? 32 What processes might be included to promote ongoing quality improvement? 1.8. 5. Quantitative evaluation (on a scale of 0 to 10) How satisfied are you with the CPC development and implementation process overall? On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0= not at all satisfied, and 10 = extremely satisfied: How useful is the CP that has been developed? On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0= not at all useful, and 10 = extremely useful How successful has the CPC project been in smoothing out patient pathways and information flow between clinicians and health services providers at all levels of the system? On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0= not at all successful, and 10 = extremely successful How successful has the CPC project been in improving patient experience of treatment? (or will be if implemented) On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0= not at all successful, and 10 = extremely successful How successful has the CPC project been in improving patient outcomes? (or will be if implemented) On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0= not at all successful, and 10 = extremely successful Summary of key findings. Invitation to raise any other issues/comments Thank and Close 33 34