Review of Fuel Poverty in Scotland

REVIEW OF FUEL POVERTY IN SCOTLAND

Scottish Government

May 2008

1

Foreword

The Scottish Government is committed to creating a more successful country, with opportunities for all of Scotland to flourish, through increasing sustainable economic growth. There is no place for fuel poverty in such a society.

Fuel poverty is a real issue for thousands of Scottish households who are struggling to pay their fuel bills and keep their homes warm. In the face of continuing high fuel prices, more and more are falling into fuel poverty. The effects on people’s quality of life can be profound.

This review sets out what has been achieved so far in the pursuit of the target to end fuel poverty in Scotland by 2016 as far as is reasonably practicable. It concludes that there is much to do to get back on track and that the existing fuel poverty programmes - the Warm Deal and the Central Heating Programmes - whilst well intentioned, have lost their way and urgently need reform. The review highlights how, under our current devolution settlement, we have direct control over measures to improve the energy efficiency of the home. However, this is only one of the three principal factors affecting the level of fuel poverty. Through the National

Conversation, we are exploring what options there are for further devolved powers to also be able to influence incomes and fuel prices in Scotland.

We can’t do this alone. We want to work in partnership with others to reform the programmes and set a clear direction for the future. That is why we are reestablishing the Scottish Fuel Poverty Forum with an independent Chairperson. The

Forum will meet over the summer to reflect upon the review and consider options for change, and will report to Ministers in the autumn. We will work with energy companies, charities, local authorities and housing associations in Scotland, and we will continue to urge Westminster to take more action.

It is clear that there are challenges ahead, but we are committed to doing what we can to meet the target. In an energy-rich country like Scotland there is no room for fuel poverty.

Nicola Sturgeon, MSP

Deputy First Minister and Cabinet Secretary for Health and Wellbeing

2

CONTENTS

Foreword

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1. Introduction

The need for a review

2. Fuel poverty – definitions, causes and extent

Definitions of fuel poverty across the UK

Definitions in other countries

Causes of fuel poverty

Effects of fuel poverty

Changes in the extent of fuel poverty

Factors affecting fuel poverty in rural areas

Improvements in housing energy efficiency

Eliminating fuel poverty – the scale of the challenge

Conclusion

3. Measures to tackle fuel poverty – influence and delivery

Scottish Government powers

Influencing household incomes

Influencing fuel prices and other action by fuel companies

Delivering household central heating and insulation programmes

Central Heating Programme

Targeting of the CHP

Impact on fuel poverty

The shift from first-time installations to replacements

Delivery of the programme

Waiting times

Value for money and controlling costs

Warm Deal

Interaction with EEC/CERT

Conclusion

24

2

5

8

10

3

4. Fit with Scottish Government strategic objectives

Relationship to policy on a fairer Scotland

Relationship to policy on housing repairs and improvements

Relationship to policies on climate change and domestic energy efficiency

Conclusion

5. Conclusions of the review

Despite the successes of our programmes, fuel poverty continues to grow

Fuel poverty is more prevalent in Scotland

The definition makes the target challenging

Fuel poverty is likely to increase further with fuel price rises

Causes and action on tackling fuel poverty

Energy efficiency measures are not enough

The Central Heating Programme now largely provides replacement systems

Existing fuel poverty programmes are not focussed on the fuel poor

Need for better fit with our strategic objectives

A national programme may be less flexible

The programmes may be displacing CERT spending in Scotland

Need for collaborative working

40

45

4

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Purpose of the review

Fuel poverty, a situation in which a household cannot afford to heat the home to a satisfactory standard, can reduce people’s quality of life. In Scotland, the levels of fuel poverty have been increasing since 2002. The most recent data available, for

2005-06, estimated that, in Scotland almost 1 in 4 households are fuel poor; more than 3 times the proportion of English households. We expect these numbers to have risen further with recent energy price increases.

The Scottish Government is committed to ensuring, so far as reasonably practicable, that people are not living in fuel poverty in Scotland by November 2016. This reflects the requirements of Section 88 of the Housing (Scotland) Act 2001, as elaborated by the Scottish Fuel Poverty Statement published in August 2002.

The review recognises what has been achieved in pursuit of the target, assesses why we are not making the progress that was intended and examines the potential to improve and build upon current policies and programmes to ensure that we can get back on track to end fuel poverty in Scotland.

Prognosis for eradicating fuel poverty by 2016

The number of households in fuel poverty in Scotland has been rising consistently since 2002. In 2005/06, an estimated 543,000 households (23.5% of all households) were classified as fuel poor. Fuel poverty is particularly high in rural areas due to a combination of demographic factors (more older households), infrastructure

(properties off the gas grid) and matters relating to the housing stock (more detached and hard to insulate homes).

There are three principal factors that determine the number of households that are fuel poor: fuel prices, household incomes and the energy efficiency of housing. The devolution settlement means that, whilst the Scottish Government can and does seek to influence incomes and fuel prices, the powers to control these factors lie with

Westminster. Its response to fuel poverty has therefore focussed on schemes to deal with the third factor – improving the energy efficiency of housing - through provision of central heating and insulation.

Significant improvements continue to be achieved year on year in the energy efficiency of the Scottish housing stock, partly as a result of these programmes. This has made Scottish householders warmer and more comfortable, lowered fuel bills and reduced carbon emissions, but has not been enough to stop the growth in fuel poor households, largely because of the significant upward trend in fuel prices.

Though fuel poverty has been rising across the UK, it is proportionately higher in

Scotland than in England, despite the fact that Scotland’s housing stock is more energy efficient. This is partly because o f structural factors such as Scotland’s climate, its rurality, income levels and the fact that it has a higher proportion of older people. It is also partly because Scotland has chosen to use a higher temperature in its definition of the satisfactory heating level for pensioner households.

5

With this definition and in the face of high and rising fuel prices, the prognosis for achieving the commitment to end fuel poverty, as far as is reasonably practicable, by

2016, is not good. Analysis undertaken for the review indicates that, for those who are most fuel poor, this could only be achieved by massive increases in income and changes in its distribution (amounting to billions of pounds per annum), huge reductions in fuel prices (almost a 100% reduction) or unrealistic improvements in energy efficiency (even if all Scotland’s home reached very high standards there would still be a quarter of a million fuel poor households).

Further improvements to housing energy efficiency will continue to keep fuel bills lower than they otherwise would be, make homes warmer and reduce carbon dioxide emissions. However, unless fuel prices and/or incomes change favourably as well, fuel poverty is unlikely to reduce significantly in the foreseeable future.

In a context of rising fuel prices, the extent of the increase in household incomes required to abolish fuel poverty is daunting. The “multiplier effect” that is locked into the current ‘10% of income’ definition of fuel poverty means that the real incomes of those on the margins of fuel poverty would need to rise by an amount ten times greater than any increase in fuel prices assuming constant energy efficiency of the housing stock. The indications are that fuel prices will continue to increase, in which case, despite our best efforts, fuel poverty in Scotland is likely to rise still further in future years.

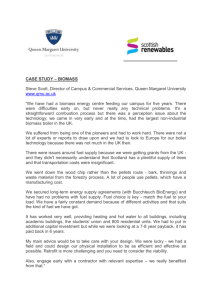

Current fuel poverty programmes and their fit with the Government’s Purpose

Our fuel poverty programmes are broadly popular with the public and have provided significant benefits to many Scottish householders

– warmer homes, lower fuel bills and reduced carbon emissions. In the face of rising fuel costs, they have not been enough to stop fuel poverty levels increasing. However, without them, fuel poverty would be even higher than it is now.

The bulk of Scottish Government investment in tackling fuel poverty is directed through the Central Heating Programme (CHP). Pensioner households were originally targeted as they have tended to be more prone to fuel poverty, but not exclusively. Around half of pensioner households in private homes were estimated to be fuel poor in 2005-06, and just over a tenth of non-pensioner households.

Amongst pensioner households, a larger proportion of households aged over 80 were fuel poor than those aged between 60 and 80. There appears to be a much closer correlation between low incomes and fuel poverty than between age and fuel poverty, with three-quarters of those in the bottom two deciles of income being fuel poor.

The Central Heating Programme has been instrumental in bringing Scotland to the position where a house lacking central heating is a rarity. However, while investment in this programme is badged under “fuel poverty” it is now, in effect, a programme to provide free central heating systems to pensioners, regardless of their fuel poverty status. Only around half of the expenditure on the programme was directed to fuel poor households in 2005-06.

6

The CHP has drifted from its original purpose of providing central heating to pensioners without it, to being almost entirely a programme for central heating replacement. Replacements offer less gain, in either fuel poverty or environmental terms, than first time installations. Given demographic trends, and the fact that systems have a finite life, the emphasis on replacements offers the prospect of a self-perpetuating programme with growing waiting lists. Low income households without central heating are, in effect, queuing behind fuel-rich households requesting replacement systems that, in many cases, they could easily afford to install themselves.

The Warm Deal (insulation) programme is better value-for-money in energy efficiency/carbon terms than the CHP. There are also fewer delivery problems in this partially locally managed scheme. However, the Warm Deal is not well integrated with UK programmes, such as the Energy Efficiency Commitment, and its successor

(CERT), which may mean Scottish Government resources are displacing those that could be taken up from the fuel companies. Similar concerns relate to the insulation aspects of the CHP.

The Scottish Government’s Purpose is to focus government and public services on creating a more successful country, with opportunities for all of Scotland to flourish, through increasing sustainable economic growth. This review considers how tackling fuel poverty can contribute to this overall Purpose, through creating a

Scotland where growth reduces inequalities between individuals (solidarity) and regions (cohesion), and contributes to reducing carbon emissions (sustainability).

The review examines the fit of the programmes with the new strategic objectives set out by the Scottish Government. It finds that there is not a good fit between definitions of “fuel poverty” and those of “income poverty” being used as part of our strategy to tackle poverty and disadvantage under the Government Economic

Strategy. While current programmes contribute to greener objectives, the CHP is not particularly cost-effective in this respect, and its poorly targeted grant-led approach does not sit well alongside policies on housing repairs and improvements which emphasise the responsibilities of the home owner.

Next Steps

This review may provide a useful starting point for a debate on the way forward for tackling fuel poverty. The complex range of factors affecting fuel poverty means that stakeholders at UK, national and local level all have a role to play

– including energy companies, charities and the insulation sector – as well as all parts of Government.

The Scottish Fuel Poverty Forum provides a platform for this and stakeholders have requested that it be re-established with an independent chairperson, to provide the opportunity to contribute to the debate and help shape the future direction of policy.

There is an opportunity to improve and build on current programmes to ensure that they operate fairly across Scotland, and that available resources make the most impact to end fuel poverty. There is an opportunity to strengthen links with related policies such as tackling poverty and disadvantage, promoting energy efficiency and addressing climate change, as part of progress towards a wealthier, fairer and greener Scotland.

7

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 This report sets out the findings of an internal review of the Scottish

Government’s approach to tackling fuel poverty. The review considers the extent of fuel poverty in Scotland; and examines how effective current programmes have been in making progress towards our target to end fuel poverty, as far as is reasonably practicable, by 2016.

The need for a review

1.2 The Scottish Government is committed to ensuring, so far as reasonably practicable, that people are not living in fuel poverty in Scotland by November 2016.

This reflects the requirements of Section 88 of the Housing (Scotland) Act 2001, as elaborated by the Scottish Fuel Poverty Statement published in August 2002. The next formal report on progress towards this objective is not required until 2010, however, for a number of reasons this is an opportune time to take stock and consider the way forward for this policy.

1.3

The Scottish Government’s Economic Strategy sets out how we will support businesses and individuals and how, together, we can deliver the following Purpose: to focus the Government and public services on creating a more successful country, with opportunities for all of Scotland to flourish, through increasing sustainable economic growth. By sustainable economic growth we mean building a dynamic and growing economy that will provide prosperity and opportunities for all, while ensuring that future generations can enjoy a better quality of life too. Decisions on all

Government priorities and policies, including the fuel poverty programmes we have inherited from previous administrations, need to be taken in the light of this Purpose.

1.4 The Scottish Budget Spending Review has identified significant resources -

£46m per annum for 2008-2011 – for programmes directly targeting fuel poverty. We need to ensure that these resources, alongside other housing and energy efficiency schemes, are marshalled effectively to ensure real progress is made over the

Spending Review period and beyond to 2016. The Scottish Government’s main fuel poverty programmes - the Central Heating and Warm Deal programmes - have been in operation for 7 and 9 years respectively and we are now almost halfway, in terms of time elapsed, to our ultimate 2016 target. Most significantly, data is now beginning to show a consistent pattern which demonstrates that despite the successes of these programmes in terms of making many Scottish homes warmer and more comfortable, fuel poverty itself has, in fact, been increasing, rather than decreasing.

This means that the outcome milestones originally set by the previous administration will not be achieved when the 2006-7 figures are published in late 2008. Given this context, there is a clear need to examine and challenge current policies and programmes.

1.5 The review recognises what has been achieved, assesses why we are not making the progress previous administrations had planned for and examines the potential to improve and build upon current policies and programmes to ensure that we can get back on track to end fuel poverty in Scotland. It recognises the important role of fuel prices and household incomes, which are primarily the responsibility of Westminster, in determining levels of fuel poverty. Action by the

8

Scottish Government has focussed on the third primary determinant of fuel poverty

– household energy efficiency – with programmes to fit efficient central heating and effective insulation. The review examines the current programmes to ensure that they are operating fairly across Scotland and that available resources are going where they can make the most impact on fuel poverty.

1.6 The review takes place in the context of the

Government’s Purpose and the new set of strategic objectives that flow from this, including a new relationship with local government, as outlined in our Concordat. As well as improving our approach to tackling fuel poverty, the review therefore also considers how we can strengthen links with related policies such as the need to address poverty and disadvantage, and tackle climate change as part of our progress towards a wealthier, fairer and greener Scotland within the over-arching aim of sustainable economic growth.

1.7 In taking forward our fuel poverty programmes we need to engage effectively with stakeholders in Scotland. The Scottish Fuel Poverty Forum was set up in early

2003 with a remit "to work collectively towards .. eradicating fuel poverty so that from

2016 no person should have to live in Fuel Poverty in Scotland." The Forum was chaired by a Scottish Government official and membership included a range of public and voluntary bodies, as well as the three main energy supply companies. The

Forum contributed towards delivering the objectives in the Fuel Poverty Statement.

However, it had always been the intention to review its role after about three years to ensure that it continued to meet current need and to contribute effectively towards achieving the 2016 fuel poverty target. The Forum last met in July 2006, and stakeholders have requested that it be re-established with an independent chairperson, to provide the opportunity to contribute to the debate and help shape the future direction of policy.

9

2. FUEL POVERTY – DEFINITIONS, CAUSES AND EXTENT

2.1 This part of the review describes what fuel poverty is and how it has been defined; examines why it is important to tackle it; and presents information on the extent of fuel poverty across Scotland and how this has changed since the commitment to tackle fuel poverty was introduced. It presents evidence that fuel poverty has been growing at the same time that the energy efficiency of Scotl and’s housing stock has been improving. Data modelling is used to illustrate the scale of the challenge required to fully eliminate fuel poverty.

Definitions of fuel poverty across the UK

2.2

“Fuel poverty” can loosely be defined as a situation in which a household is not able to heat a home to an acceptable standard at an acceptable cost, in relation to its income. It can thus be defined more specifically in a variety of ways depending on the judgements and assumptions made about what constitutes “poverty” (for example, which elements of income are included or excluded; the proportion of income considered acceptable to spend on heating) and the level of heating it is reasonable for a household to enjoy (for example, what is an acceptable temperature standard?). The nature of the definition chosen has a significant impact on the extent of fuel poverty; its distribution, both geographically, and between population groups; and the nature, extent and cost of the interventions required to address it.

2.3 The 2002 Scottish Fuel Poverty Statement used the following definition of fuel poverty :

“A household is in fuel poverty if, in order to maintain a satisfactory heating regime, it would be required to spend more than 10% of its income (including Housing Benefit or Income Support for Mortgage Interest) on all household fuel use.”

The Statement also established that households needing to spend more than 20% of their income on fuel use would be regarded as being in extreme fuel poverty.

2.4 In Scotland, a

“satisfactory heating regime” for the main living area in the home for all pensioners aged 60 upwards (and also those who are long-term sick and disabled) is regarded as being that the room must reach a temperature of 23 degrees Celsius for 16 hours a day, 7 days a week. This is a more demanding requirement than for non-pensioner households, where the requirement is 21 degrees Celsius for 9 hours per day weekdays and 16 hours per day weekends.

2.5 In 2001, Scotland chose to use a more demanding satisfactory heating regime for pensioners, the long term sick and disabled people than in the rest of the UK. In

England, irrespective of whether or not they are headed by pensioners, all households are judged to require a 21 degree Celsius temperature in their main living area, and an adjustment is made for under-occupancy. Thus pensioners, the sick and disabled people in Scotland are deemed to require warmer homes than their counterparts in England. This is significant given that these groups together make up more than one third of Scottish households.

10

2.6 These standards relate to internal temperatures and therefore cannot be justified on the basis of a longer heating season in Scotland which is already factored into the calculations. The Scottish definition means that, for a given level of fuel prices, the improvement in energy efficiency and/or increase in income required to take a pensioner household out of fuel poverty in Scotland is significantly greater than in the rest of the UK.

2.7 In 2005/06, 24% of the population in Scotland were classed as fuel poor compared with only 7% of households in England. This is despite the fact that the energy efficiency of Scottish homes is generally better than those in England 1 .

However, this definitional difference is only one of the reasons why the rate of fuel poverty is 3.4 times greater in Scotland than in England. Other reasons for the higher rate in Scotland include demographic factors (a higher proportion of pensioners and the long term sick living on essentially fixed incomes)

; Scotland’s greater rurality

(which correlates to factors which increase fuel costs, such as lack of access to the gas grid), and a colder climate and generally higher wind speeds (especially in

Northern-most regions) leading to a longer heating season.

Definitions of fuel poverty in other countries

2.8 Over the course of this review, we have been unable to find evidence which indicates that countries outside the UK, have defined fuel poverty in anything like similar terms to those applied in Scotland. Programmes do exist to assist low income families with the costs of high fuel bills – in the USA, this is sometimes referred to as

“weatherisation payments”. For example, New England Farm Workers’ Council

(NEFWC) has managed the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program

(LIHEAP) for the City of Springfield since 1982. LIHEAP assists low-income households, including owners and renters, in meeting the high cost of home heating.

LIHEAP pays benefits of fixed amounts based on household income. An additional benefit is available to households having a high energy burden. The agency makes utility payments to the primary heating vendor - oil, gas, electric or other. However, while these programmes address similar issues to our fuel poverty programmes, the trigger for action is low income rather than fuel poverty and the focus is on subsidising consumption, rather than seeking to reduce it, through energy efficiency measures.

Causes of fuel poverty

2.9 The three main factors that influence the level of fuel poverty, and which are amenable to a greater or lesser extent, to Government influence 2 are :

fuel prices

1 A direct comparison is not straightforward, but using the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP

2005) scale, the mean rating for Scotland’s housing stock in 2004-05 was between 55 and 59, compared to a score of 48 for England’s housing stock, in 2005.

2

Under-occupation can also contribute to fuel poverty, which helps to explain the prevalence of fuel poverty in single person households.

11

household incomes; and

energy efficiency of the housing stock.

The relative importance of each factor varies depending on the period examined. For example, analysis of the reduction in fuel poverty between 1996 and 2002 is shown to be attributable mainly to increases in household income (50%); and decreasing fuel prices (35%), with energy efficiency improvements playing a lesser role (15%).

2.10 The definition of fuel poverty and its inter-dependence with these factors means that a household can move into, or out of fuel poverty at different times and for a variety of different reasons. For example, a person who stops work temporarily to undertake a course of study may move into fuel poverty and then move back out of fuel poverty on their return to employment. A household may be brought into fuel poverty when fuel prices rise, but leave fuel poverty when these fall.

Effects of fuel poverty

2.11 Fuel poverty can impact negatively on quality of life and health. For example, households on low incomes that have to spend a high proportion of that income on fuel have to compensate in other parts of their family budgets. This can lead to poor diet, or reduced participation in social, leisure and educational activities.

Overcrowding, caused by families having to remain in limited heated areas of the homes, can also adversely affect the education of young people.

2.12 However, it is important to note that the relationship between indoor temperatures, fuel poverty and ill-health is a complex one. There is a widely held opinion that installing central heating and ensuring warm homes will reduce excess winter deaths 3 (EWD). There is, however, no hard evidence for this. Indeed the term "excess" winter deaths is in some ways misleading in suggesting extra or avoidable deaths. There is no single common cause behind these deaths and very few indeed are caused by hypothermia. Scotland has similar levels of excess winter deaths to other UK countries, but lower levels than Southern European countries such as Portugal. Low levels in the Scandinavian countries may well reflect not only high standards of home heating and insulation but effective protection against outdoor cold.

2.13 Various research projects over recent years have set out to consider the possibility of a correlation between fuel poverty and excess winter deaths (EWDs).

However, while this research has served to highlight the complexities of the issue, it did not conclusively establish such a link. Research by Howieson and Hogan

(2005) 4 identified a link between deprivation and excess winter deaths highlighting that the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) is positively correlated with

EWD by region. This relationship suggests that a range of issues are likely to be a factor in EWDs - including health inequalities, income and lifestyle rather than

3 Excess winter mortality is calculated as winter deaths (deaths occurring in December to March) minus the average of non-winter deaths (April to July of the current year and August to November of the previous year).

4

Multiple deprivation and excess winter deaths in Scotland, Journal of the Royal Society for the

Promotion of Health, February 2005 pp18-22 ISN 1466 4240.

12

simply climatic variations, or having an energy efficient house. GROS 5 statistics show that numbers of EWDs in Scotland are greatest in the area of Greater Glasgow

Health Board, however when compared against population statistics, there is very little geographic variation across the country. If colder temperatures and energy inefficient housing play a significant part in these deaths we would expect to see greater levels in areas which are colder or have housing stock which is difficult to make thermally efficient.

2.14 Research by Edinburgh University commissioned by the former Scottish

Executive in 2002 found that two years after installation the Central Heating

Programme had had no clear impact on recipients’ current health or their use of health services or medication. Recipients were actually more likely than the comparison group to report receiving a first diagnosis of a nasal allergy (such as hay fever) during the evaluation period. Receipt of central heating under the programme was associated with a reduced probability of receiving a first diagnosis of heart disease and of high blood pressure. This finding must be treated with much caution, however, as it was based on self-reported data, rather than clinical records and was not accompanied by any reduction in the use of medical services or medication which might be expected as a consequence. The Programme did significantly reduce condensation, dampness and cold in recipients’ homes, long-term exposure to which is associated with poor health. A further fourteen outcome measures representing specific symptoms and health conditions exhibited no significant associations with the receipt of heating under the Programme.

Changes in the extent of fuel poverty

2.15 The main source of information on fuel poverty in Scotland is the Scottish

House Condition Survey (SHCS). Prior to 2003, surveys were conducted in 1991,

1996 and 2002. Since then they were moved to a continuous format to allow more flexibility in content and the ability to more closely monitor Ministerial targets.

Figure

1 shows that from 1996 to 2002 the number of fuel poor households in Scotland fell substantially from around 36% to 13% 6 . However, since 2002 fuel poverty levels have increased every year with a particularly large increase to 2005/06. In 2002,

13% of households (286,000) were assessed as fuel poor, rising to 15.4% of households (350,000) in 2003/4. This rose again to 18.2% of households (419,000) in 2004/05 and then to 23.5% of households (543,000) in 2005/06. 7.5% of households (173,000) in 2005/06 were estimated to be in “extreme fuel poverty” (i.e. having to spend in excess of 20% of their income on fuel). This means that almost a third of those in fuel poverty are in extreme fuel poverty.

5 General Register Office for Scotland

6 This comparison uses two different definitions of fuel poverty. A comparison using the same definition results in a fall from 36% to 9%. See the 2002 fuel poverty report for further details: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Statistics/SHCS/FuelPoverty

13

Figure 1: Households in Fuel Poverty 1996-2005/6 (%)

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

1996 2002 2003/4 2004/5 2005/6

Survey year

2.16 Changes in fuel prices were an important factor in both the reduction in numbers in fuel poverty between 1996 and 2002 and in the subsequent increase.

Because of the small sample sizes in the 2004/5 and 2005/6 surveys, the precision of any estimates of the effect of improved energy efficiency measures will be poor as will estimates of the offset of those improvements against the impact of fuel price increases. However, in general terms, re-running the fuel poverty calculations on the

2005/6 sample using 2004/5 fuel prices up-rated for general inflation showed that there would have been no statistically significant change in fuel poverty between

2004/5 and 2005/6 had fuel prices not increased in real terms over the period.

2.17 Figure 2 and Table 2 show that households living in dwellings with low levels of energy efficiency (i.e. t hose with ‘poor’ scores under the National Home Energy

Rating (NHER) system) are more likely than those with higher NHER scores to be fuel poor. Not surprisingly, fuel poverty is also closely correlated with low incomes.

Almost all of those with a household income of less than £100 per week are fuel poor. Fuel poverty is, however, lowest in social housing, particularly the housing association sector (17% of households). This is likely to be due to the preponderance of flats, younger stock age profile and Government refurbishment targets affecting the socially rented sector. Fuel poverty is highest in owner-occupied dwellings (25 % of households).

14

Figure 2: Households in fuel poverty by tenure, NHER band, household type, household income and urban/rural (%) owner-occupier

LA/other public

HA/co-op private-rented

Poor

Moderate

Good single adult small adult single parent small family large family large adult older smaller single pensioner

< £100 p.w.

£100 -199.99 p.w.

£200 -299.99 p.w.

£300 -399.99 p.w.

£400 -499.99 p.w.

£500 -699.99 p.w.

£700+ urban rural

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Percentage in Fuel Poverty

2.18 From Figure 2 and Table 2 , it can be seen that just under half of single pensioner households (181,000) and around two fifths of older smaller households 7

(143,000) were fuel poor, making them more likely than other household types to experience fuel poverty. 24% of single adult households (81,000) were also in fuel poverty. Family and non-pensioner couple households were least likely to be fuel poor.

2.19 Table 2 shows that households with partial central heating or no central heating (of which there are relatively few in Scotland) are around twice as likely to suffer fuel poverty as those with full central heating.

In terms of their main fuel source, twenty per cent of gas users are fuel poor compared to 32% of electricity users and 37% of oil users. Furthermore those who use oil or ‘other fuel types’ (not gas or electricity) are around three times more likely to experience extreme fuel poverty than gas users.

7 Mostly pensioner couples

15

Table 2: Fuel poverty by dwellings and household characteristics (%)

Tenure

Owner-occupier

LA/other public

HA/co-op

Private-rented

Private

Social

Central heating extent

Full

Partial

No central heating

Primary heating fuel

Gas

Electricity

Oil

Other fuel type

NHER band

Poor

Moderate

Good

Household type

Single adult

Small adult

Single parent

Small family

Large family

Large adult

Older smaller

Single pensioner

Weekly income band

< £100 p.w.

£100 -199.99 p.w.

£200 -299.99 p.w.

£300 -399.99 p.w.

£400 -499.99 p.w.

£500 -699.99 p.w.

£700+ p.w.

Urban/rural

Urban

Rural

All Scotland

Unweighted sample size

Not Fuel Poor Fuel Poor

% %

75

78

83

77

75

80

78

62

59

80

68

63

59

42

69

88

1

42

78

89

95

98

99

76

89

86

92

88

86

59

53

79

66

77

2,318

25

22

17

23

25

20

22

38

41

20

32

37

41

58

31

12

99

58

22

11

5

2

1

24

11

14

8

12

14

41

47

21

34

23

785

Extreme Fuel

Poor 8

%

7

12

16

6

8

16

18

25

11

2

78

16

3

1

1

3

5

18

14

5

4

2

1

6

14

7

263

9

3

2

9

9

2

Unweighted sample size

2,092

505

296

210

2,302

801

2,866

155

82

2,261

471

247

124

167

1,576

1,360

130

654

638

479

383

449

370

407

531

165

445

216

310

503

526

2,411

692

3,103

8 Extreme fuel poverty is a subset of fuel poverty i.e. those who are extreme fuel poor are included in the figures for fuel poverty.

16

Factors affecting fuel poverty in rural areas

2.20 Table 2 shows that rural households are more susceptible to fuel poverty

(34% are fuel poor) than urban households (21%). 14% of rural households are in extreme fuel poverty, making extreme fuel poverty more than twice as likely for a rural household as for an urban household. The patterns revealed in the survey data, taken together with the particular definition of fuel poverty adopted in Scotland, with its differential heating regime for pensioner households, provide a clear indication of the types of locations across Scotland that are more likely to be vulnerable to fuel poverty. Most of these factors, as outlined below, are generally more prevalent in rural areas.

2.21 In terms of social and demographic factors , fuel poverty will tend to be higher in areas where there is a higher proportion of :

pensioner households;

long-term sick and disabled households;

single person households.

In terms of the housing stock , there will be tendency for greater levels of fuel poverty in areas where there is a higher proportion of :

houses, especially detached houses;

stock built using solid wall construction, for example, stone built or built using non-traditional construction methods;

older housing.

In terms of the energy infrastructure , there will be tendency for greater levels of fuel poverty in areas where there is limited access to the gas grid – again, this is more likely in rural rather than urban areas. The chances of a household that is ‘off the gas grid’ being fuel poor are approximately double that of a household ‘on the gas grid.

’ Many houses off the gas grid are in also the North of Scotland, where the heating regime used for modelling is stricter to account for the longer heating season and higher wind speed. Similarly, many of these houses are detached and/or have stone walls making them harder to insulate using conventional means.

Improvements in housing energy efficiency

2.22 The SHCS also shows that energy efficiency has been consistently increasing in recent years at the same time that fuel poverty has also been on the rise. Table 3 and Figure 3 show how the energy efficiency of the housing stock has improved. In

2002, an estimated 31% of dwellings achieved a “good” NHER rating of 7 or above.

By 2005/6 this proportion had risen to an estimated 47%. Correspondingly fewer dwellings were given a poor rating in 2005/6 than in 2002.

17

Table 3: Change in banded NHER by tenure 2002-2005/6 ( %)

NHER Band

All

Unweighted sample size

All tenures

2002

2003/4

2004/5

2005/6

Private sector

Poor Moderate Good

Row Percentages

8

6

5

4

60

54

51

48

31

40

44

47

2002

2003/4

2004/5

2005/6

Social sector

2002

9

8

6

5

65

58

57

55

27

35

38

40

2003/4

2004/5

2005/6

6

2

2

1

51

43

35

32

43

56

63

67

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

14,965

3,088

3,085

3,146

10,107

2,220

2,305

2,340

4,858

868

780

806

2.23 Table 3 shows that improvements in energy efficiency of social rented dwellings have been greater than those for the stock as a whole. This is likely to reflect the impact of fuel poverty programmes on this sector, as well as housing improvement programmes linked to the achievement of the Scottish Housing Quality

Standard. In 2005/6, about two thirds of social rented dwellings had a “good” NHER rating, compared to 43% in 2002. Over the same period, the proportion of private sector dwellings rated “good” increased from 27% to 40%. Only about 3% of the housing stock has no central heating. A further 4% have only partial central heating.

Table 4 shows that, of those 3% without central heating, 60% have “poor” NHER ratings, compared to just 2% of those with full central heating - with almost half of those with full central heating having ‘good’ ratings.

18

Figure 3: Mean NHER by tenure, type of dwelling, household income and urban/rural indicator owner-occupier

LA/other public

HA/co-op private-rented

Detached

Semi-detached

Terraced

Tenement

Other Flats

< £100 p.w.

£100 -199.99 p.w.

£200 -299.99 p.w.

£300 -399.99 p.w.

£400 -499.99 p.w.

£500 -699.99 p.w.

£700+ urban rural

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Mean NHER score

2.24 Despite these improvements, problems remain. Table 4 shows that 14% of dwellings in the private rented sector are rated “poor”, compared to an average of

4% across all sectors. Those who use ‘other fuel types’ 9 such as solid fuels are over

30 times more likely than those who use gas to have a ‘poor’ NHER score. Urban dwellings are around twice as likely to have a good NHER rating and around six times less likely to be rated ‘poor’ than those in rural areas. This may be partly explained by factors such as rural dwellings being more likely than those in urban areas to be off the gas grid, and so must use oil or solid fuels which are more costly.

Many of these homes are also stone built or of non-traditional construction and so cannot benefit from energy efficiency measures such as cavity wall insulation.

Consequently, these types of houses and in particular detached houses have poorer energy efficiency than flats.

9 Other fuel types includes solid fuels such as coal, smokeless fuels, wood and peat, and community heating. Community heating systems have been included in this category as their sample size in the

SHCS is too small to allow them to be a separate category but they would generally be expected to have better energy efficiency ratings than solid fuel systems.

19

Table 4: NHER band by dwelling and household characteristics (%)

NHER band

Poor

%

Tenure

Owner-occupier

LA/other public

HA/co-op

Private-rented

Private

Social

Dwelling type

Detached

Semi-detached

Terraced

Tenement

Other flats

Age of dwelling

Pre-1919

1919-1944

1945-1964

1965-1982

Post-1982

Central heating extent

Full

Partial

No heating central

Primary heating fuel

Gas

2

10

60

4

1

2

14

5

1

10

3

2

3

3

14

4

3

2

0

1

12

15

33

Electricity

Oil

Other fuel type

Household type

Single adult

Small adult

Single parent

Small family

Large family

Large adult

Older smaller

Single pensioner

Urban/rural Indicator

Urban

Rural

All Scotland

2

13

4

5

5

1

4

3

2

7

3

Moderate

%

48

56

38

44

63

79

43

45

52

29

49

46

55

56

44

63

58

52

50

25

61

65

44

32

35

56

34

28

44

55

32

46

61

48

Good

%

50

43

70

47

51

43

37

52

23

38

45

48

75

29

32

53

65

62

40

65

70

41

40

67

49

34

2

56

25

6

24

52

25

47

Total

%

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

Unweighted sample size

2,120

506

300

220

2,340

806

794

713

734

530

375

525

411

784

820

606

2,900

159

87

2,277

482

257

130

419

539

168

450

218

315

508

529

2,430

716

3,146

20

Eliminating fuel poverty

– the scale of the challenge

2.25 The improvements in energy efficiency that have been achieved across all housing tenures in recent years are significant and welcome. Further progress will be more challenging as the focus shifts to properties that are harder, or to put this another way, more expensive, to treat 10 . Nevertheless, improving household energy efficiency must be an important component of any successful fuel poverty strategy.

However, in terms of our aim of eliminating fuel poverty, as far as practicable, this positive progress needs to be set against the countervailing influence of significant rises in fuel prices.

2.26 Figure 4 shows how fuel prices have risen markedly in 2005-6 with a 30% real rise in gas prices and 20% real rise in electricity prices between May 2005 and

May 2006. Analysis undertaken for this review has revealed that fuel prices would need to fall by almost to zero to eliminate fuel poverty entirely. Indeed, fuel prices would have to fall by something like 80% even to eradicate only 80% of fuel poverty.

11 . This is extremely unlikely in the medium or even the long term, and, indeed, further significant fuel price increases have been announced in recent weeks.

Figure 4: Fuel Price Indices adjusted for inflation , (1990 =100)

150

100

50

0

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Gas

Electricity

Source: BERR Quarterly Energy Price Tables. May each year.

10

Hard to treat houses are generally regarded as those that are either expensive or technically difficult to insulate (such as those with solid walls that cannot receive cavity wall insulation; or with roofs that are flat or have restricted loft space); or are remote from the supply of mains gas meaning that it is difficult or expensive to install heating that uses cost effective fuel. Houses that are difficult to insulate include pre-1930s stone built properties and system built post-war buildings using concrete or metal construction for solid walls or with flat roofs. Multi storey blocks could also be regarded as hard to treat.

11 This is based on statistical modelling using SHCS data which can be used to fix the energy efficiency of the stock and incomes at today’s levels and then calculate the fuel price reduction required to eliminate fuel poverty. The reason why the fuel price reduction is so large is because there are groups of people in Scotland whose incomes are so low and/or their homes are so energy efficient that the current level of fuel prices essentially places them at the far end of the fuel poverty curve. These people require extremely large reductions in fuel prices to lift them out of fuel poverty – as defined - i.e. to bring them below the 10% line.

21

2.27 There are also limits to how far energy efficiency improvements can take us towards meeting the ultimate goal of eliminating fuel poverty, in the context of high and rising fuel prices. Statistical modelling has shown that, even if all houses were rated as ‘good’ under the NHER system (i.e. every house achieved a score of 7), or, in fact, even if all households achieved the highest NHER rating (i.e. a score of 10 out of 10), then, given today’s levels of fuel prices and incomes, fuel poverty in

Scotland would still be present in a large number of households (see Table 5 ). It should be stressed th at improving all Scotland’s homes to an NHER level of 7 would be extremely expensive. Improving the stock to an NHER level of 10, would probably be impossible without significant amounts of demolition and new build to higher environmental standards. Even if it were possible to achieve such high energy efficiency standards, it is estimated that almost a quarter of a million fuel poor households would remain in Scotland.

12

Table 5: Number and rate of fuel poverty given theoretical energy efficiency improvements

Current efficiency levels energy

Number

543,000

Rate

23.5%

All stock attains NHER 7

All stock attains NHER

10

422,000

231,000

18.2%

10.0%

Source: SHCS statistical modelling exercise based on 2005-6 data

2.28 Analysis has also shown that tackling fuel poverty - as defined - through household incomes alone is not realistically achievable. The Scottish Government has modelled the increases in income required to establish how far they would have to rise to eliminate fuel poverty in Scotland. This i nvolves ‘freezing’ the energy efficiency of the stock and also fuel prices at 2005-6 levels. The results suggest that total personal incomes in Scotland would have to rise overall by somewhere between £3-3.5 billion per annum 13 . Those around the margins of fuel poverty and in lower income groups in particular would require substantial income increases 14 . To eliminate fuel poverty at 2005-06 levels would have required this additional income to be distributed across household groups in a particular way so as to compensate the fuel poor as appropriate. If the additional income required to remove fuel poverty was to come from the Scottish Government Budget, this would account for over 10% of devolved expenditure every year. In simple percentage terms, the incomes of the fuel poor would have to rise by an average of 60%, including increases of between

12 Statistical modelling is used to fix fuel prices and incomes at current levels and estimate what fuel poverty would be under two scenarios for energy efficiency in the stock, NHER 7 (all houses rated

‘good’) and NHER 10 (all houses reach the current highest standard for energy efficiency, for example, equivalent to new build flats built to the latest building standards).

13 Total household income in Scotland was in the region of £67 billion in 2005-06.

14 This time the statistical model fixes the energy efficiency of the stock and fixes fuel prices and calculates for each household group the increase in income required to take them out of fuel poverty.

This could be the required increase in wages for those who are employed, or the increase required in benefits and pensions for those who are not in work or who are pensioners. The reason why the increase is so large is because, again, fuel prices are so high relative to some very low incomes that huge increases are required to bring some households below the 10% threshold.

22

75% and 80% for pensioner groups. Again, such sums are prohibitively high and suggest that to fix the problem with higher incomes (or effectively a redistribution of income) alone is unlikely to be sustainable, and is not realistic under the current devolution settlement.

2.29 Such a large extra income requirement highlights how the definition of fuel poverty and its use of the

‘10% rule’ (in which fuel poverty is deemed to affect those paying more than 10% of their income on energy) dictates the scale of the problem.

Using the current definition of fuel poverty , a £100 increase in the annual fuel bills of a particular household would require a compensating rise in income of at least

£1,000 if the household was to maintain its position, in fuel poverty terms, compared to before the price increase. The nature of the fuel poverty definition means that the level of income compensation required to keep the fuel cost/income ratio of a household steady is 10 times greater than the fuel cost increase itself. This implies that, to hold the numbers in fuel poverty static, Scottish or UK governments would have to find resources that are 10 times greater than the value of the fuel price rise every time fuel prices rise assuming that energy efficiency levels do not change.

Conclusion

2.30 This part of the report has made clear the importance of household income and fuel prices, as well as energy efficiency, in determining levels of fuel poverty. It has shown that a range of demographic, housing and infrastructural factors make fuel poverty much more prevalent and harder to tackle in rural, as opposed to urban areas. It notes that the there are particular aspects of the definition of fuel poverty that has been adopted in the UK (in particular, the “10% rule”) that make it extremely difficult to completely eliminate fuel poverty in an environment of high and rising fuel prices. This has been compounded by the specific definition of pensioner fuel poverty adopted in Scotland in 2001 which has added further to the challenge.

2.31 In the context of high or rising fuel prices, fuel poverty continues to increase, despite significant ongoing improvements to household energy efficiency. This means that current programmes – which focus on improving energy efficiency through central heating and insulation measures

– are not enough on their own to turn around fuel poverty. Continuing to improve energy efficiency will be more challenging in the future as we begin to address problems in hard-to-treat properties.

However, even if the energy efficiency of all the Scottish stock reached very high standards across the board, fuel poverty would still be a significant factor in

Scotland. Fuel prices and/or incomes would need to change substantially, alongside further major improvements to energy efficiency, in order to eliminate fuel poverty.

23

3. MEASURES TO TACKLE FUEL POVERTY – INFLUENCE AND DELIVERY

3.1 This part of the review sets out the powers available to Scottish Ministers to deliver schemes to tackle fuel poverty and those reserved to Westminster. Given this context, it describes how we are seeking to work within the devolution settlement to influence household incomes and fuel prices, which have such an important role to play in determining the number of people in fuel poverty. It then considers in more detail the delivery of the main fuel poverty schemes directly under Scottish

Government control – the Central Heating Programme and Warm Deal.

Scottish Government powers

3.2

The Scottish Government’s powers to introduce measures to tackle fuel poverty are limited by the devolution settlement. Our principal powers in relation to fuel poverty are in regard to measures to improve the energy efficiency of the home, which, as outlined in the previous chapter, is the least important of the three principal factors influencing fuel poverty. The Social Security Act 1990 enables Scottish

Ministers to make arrangements for the payment of grants for the purposes of improving thermal insulation or preventing wastage of energy. However, the

Scotland Act reserves to Westminster all matters relating to social security benefits

(which determine the incomes of many low income households) and to the regulation of energy companies (including pricing). The Scottish Government cannot therefore develop schemes of direct financial assistance for the fuel poor. Nor can it legislate in such matters as social tariffs or smart meters, even if it wished to. However, while the Scottish Government has no direct control over these matters, it is seeking to influence them as far as it can.

Influencing household incomes

3.3 The Scottish Government Economic Strategy (GES) recognises that sustainable economic growth must go hand in hand with a fairer sharing of the wealth of the country and with an absolute commitment to tackling poverty and disadvantage by improving the life chances of those who are most in need. Tackling fuel poverty must sit within these broader objectives. This must, however, take into account the complex relationship between “poverty” (essentially about incomes) and

“fuel poverty” (which depends on a complex of factors including incomes, fuel prices and energy efficiency). The relationship is examined in more detail in chapter 4.

3.4

Changes to household income are a major factor contributing to fuel poverty.

The Scottish Government has an important role in enabling the growth pf the

Scottish economy and promoting employment which may offer a route out of fuel poverty for some people. However, factors such as the level of pensions and welfare benefits are reserved to Westminster. The significant reduction in fuel poverty between 1996 and 2002 is associated with factors such as the introduction of the

Minimum Wage and tax credits, alongside reductions in fuel prices, with energy efficiency gains taking only a minor role. In the absence of further redistributive policies of this scale (with the notable exception of Pension Credit) the importance of income related policies in determining the level of fuel poverty has waned in the last few years.

24

3.5 The Scottish Government can and does, however, work with Westminster to increase household income by promoting benefit take-up and this is an important aspect of our fuel poverty programmes. The DWP estimates that up to 40% of eligible pensioners may not be claiming Pension Credit 15 - a third of which are expected to be aged over 80. It estimates that as much as between £5,800 million and £9,380 million in income related benefits including Income Support and Pension

Credit were left unclaimed in 2005-06; between 15 and 22% of the overall welfare benefits budget.

16 In an arrangement unique to Scotland, the Managing Agent for the programmes has a cross-referral agreement in place with the Pension Service and a face to face benefits entitlement check is offered to anyone of pensionable age who applies to the Warm Deal or Central Heating Programme.

3.6 There is currently no similar scheme in place for Warm Deal applicants who are not pensioners. These groups who are not eligible for central heating could also benefit from income maximisation support. Statistics show that in particular, single people need encouragement to claim all the benefits to which they are entitled. The

DWP estimates that in 2005/06 more than half of those entitled to, but not claiming,

Jobseeker’s Allowance (Income-Based) were single people under the age of 25 and the take-up of Income Support appeared to be lower amongst non-pensioners without children 17 . Take-up for Housing Benefit is lowest amongst families with children. A benefits health check provided to these householders, could complement the package of insulation measures provided under Warm Deal.

3.7 In addition, the Scottish Government has done much to indirectly enhance the disposable income available to potentially vulnerable households, as part of broader anti-poverty initiatives. For example, the Scottish Parliament has introduced free national bus travel for pensioners, as well as free dental checks and eye examinations and the universal provision of free school meals is now being piloted.

While these initiatives will increase the disposable income of many households vulnerable to fuel poverty, because of the specifics of how fuel poverty has been defined, the impact of these measures will not be reflected in the fuel poverty figures.

However, the current definition does mean that the Scottish Government’s proposals to abolish the council tax in favour of a tax based on the ability to pay would be a factor influencing fuel poverty levels.

Influencing fuel prices and other action by fuel companies

3.8 Government policies developed at Westminster to liberalise the energy markets and promote competition may have initially contributed to significant reductions in energy prices and this did play an important part in the fall in fuel poverty from 1996 to 2002. However, in more recent years, fuel prices have continued to rise and this is a major factor in the growth of fuel poverty.

15 http://www.dwp.gov.uk/mediacentre/pressreleases/2007/mar/pce-29-03-07-1.pdf

16 http://www.dwp.gov.uk/asd/income_analysis/sept_2007/0506_NSPR.pdf

17 http://www.dwp.gov.uk/asd/income_analysis/sept_2007/0506_NSPR.pdf

25

3.9 Whilst fuel prices are a matter reserved to Westminster, Scottish officials maintain good working relationships with the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR) and the Department for Environment, Food and

Rural Affairs (DEFRA). This includes: regular informal meetings; participation in the

UK-wide Energy Efficiency Partnership for Homes and contributions to consultations

(a recent example being the future of the Energy Efficiency Commitment - EEC).

Officials also maintain regular contact with Ofgem and Energywatch. In addition to the overall level of fuel prices, a number of other issues relating to the operations of fuel companies and the obligations upon them have an affect on fuel poverty. These include the use of pre-payment meters (PPM), social tariffs and the obligations of fuel companies under EEC/CERT.

3.10 Many of the poorest households may be paying more for their energy because they are unable to take advantage of competition in the energy market. This may be because their circumstances prevent them from switching energy supplier or because it would not be worthwhile for them to do so. For example, they may be without the wherewithal to switch or may be in arrears with fuel bills. For those with

PPM there may not be a choice of competitive tariffs. PPMs are popular amongst low income households as they provide greater control over payment and thus prevent arrears accruing. A PPM allows small cash payments and so is an attractive way of budgeting for fuel; particularly for those without a bank account.

Unfortunately, this method of payment can also be the most expensive; particularly when compared to direct debit payment methods which offer a discounted tariff.

3.11 As fuel prices have been rising since 2003 in response to world energy markets, the UK Government has exhorted suppliers to do more to protect vulnerable energy customers including the provision of social tariffs. Social tariffs are a low cost energy tariff designed to mitigate the impacts of high fuel prices on lowincome households. These vary across energy suppliers, as do their benefits, but are normally offered to a specific group of energy customers (for example, pensioners) and are often means tested. Perceptions of the success of social tariffs vary across Government, energy suppliers and stakeholders and are often viewed as a complementary measure to improved energy efficiency, rather than a contribution to reducing fuel poverty.

3.12 The Energy White Paper set out the UK Government’s commitment to instruct

Ofgem to evaluate the energy companies’ Corporate Social Responsibility measures including social tariffs to see how these compare in terms of supporting the fuel poor.

This review was to compare measures across the companies, highlight good practice and draw attention to areas where improvements were needed. Ofgem concluded from the review that each company had initiatives and approaches with

“worthwhile aims” providing assistance to some of their most vulnerable customers.

It furth er concluded that these initiatives should be “recognised as valuable steps which go beyond suppliers’ regulatory obligations.”

3.13 The White Paper also stated that the UK Government would introduce powers within the Energy Bill to enable the Secretary of State to require companies to have an adequate programme of support for their most vulnerable customers, and to consider the role of mandated minimum standards for social tariffs. However, the draft Energy Bill does not include such powers. We understand that this was deemed

26

unnecessary as the Ofgem review had concluded that the measures provided by the companies were effective. On 21 February 2008, energy regulator Ofgem announced an investigation into the markets in electricity and gas in response to public concern about whether the market is working effectively and customers getting a good deal. Their probe will focus on all energy customers, including those with prepayment meters, or who do not pay by direct debit.

3.14 A Fuel Poverty Summit was held on 23 April 2008, chaired by Ofgem chair Sir

John Mogg, to discuss what further action can be taken to tackle fuel poverty. The

Minister for Communities and Sport attended and proposed further measures to combat the impacts of high fuel prices in Scotland. He suggested actions should include reconvening the UK-wide Ministerial Fuel Poverty Group, transparency around Carbon Emissions Reduction Target spending by energy companies in

Scotland and sharing of Department for Work and Pensions data to help focus resources on those most vulnerable to fuel poverty.

3.15

Action on pricing needs to be seen in the context of the legal obligations faced by energy companies under the Energy Efficiency Commitment (EEC) and Carbon

Emissions Reduction Target (CERT) to deliver energy saving targets by improving domestic energy efficiency. This energy saving target is met through provision to householders of measures such as cavity wall and loft insulation, energy efficient boilers, appliances and light bulbs. A significant proportion of these savings are aimed at low-income consumers in order to alleviate fuel poverty. EEC/CERT is funded through a levy on all domestic fuel bills and thus represents a redistribution between fuel company customers, rather than direct investment by the UK

Government.

3.16 The UK Government began a new three year programme called CERT

(Carbon Emission Reduction Target), building on the previous EEC scheme, but with a stronger emphasis on carbon saving. CERT doubles the level of activity compared to EEC, and includes provision for full funding of measures for low income priority groups and the offer of discounts to those who are “able to pay”. CERT could potentially be equivalent to provision of investment in energy saving measures of around £80m per annum in Scotland - significantly more than the amount currently invested in Scottish Government fuel poverty programmes. There is anecdotal evidence that Scotland’s householders are not receiving a proportionate share of

EEC resources.

Delivering household central heating and insulation programmes

3.17 In the context of its limited powers to address the key contribution of household income and fuel prices to fuel poverty, the Scottish Government has instead focussed on seeking to improve household energy efficiency. These measures consist of a mixture of programmes to improve housing and domestic energy efficiency across the board and schemes focussed specifically on fuel poverty.

3.18 Measures to improve energy efficiency in the housing stock as a whole, include :

27

- provision of energy efficiency advice through the Energy Saving Trust and a

Scotland-wide network of energy advice centres;

- setting the highest energy requirements in the UK in the building standards for new buildings, including housing. The Minister for Transport, Infrastructure and Climate Change commissioned an Expert Panel to advise the Scottish

Government on a Low Carbon Building Standards Strategy aimed at moving the construction of new buildings, including housing, to the rigorous energy performance levels imposed in Scandinavia. The cost implications arising from its proposals are being considered;

- the introduction of Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) - linked to the

Home Report in the case of home sales - will mean that the energy performance of houses will be rated when they are constructed, sold or rented.

- introduction of minimum insulation standards through the Tolerable Standard.

3.19 Measures intended for fuel poor and/or low income households include :

- The Scottish Housing Quality Standard (SHQS) which includes a commitment to ensure all social rented houses (615,000 homes) have effective insulation and a full, efficient central heating system by 2015.

- The Central Heating and Warm Deal (insulation) programmes.

Our main programmes for tackling fuel poverty are therefore the Central Heating

Programme and Warm Deal, to which we now turn to assess in more detail.

CENTRAL HEATING PROGRAMME (CHP)

3.20 The Central Heating Programme (CHP) is a national Scottish Government programme providing a package of measures to pensioner households (i.e. those over 60). These are :

- A full, efficient central heating system;

- All suitable insulation measures 18 ;

- Cold alarm, smoke and carbon monoxide detectors;

- Energy efficiency advice;

- Optional benefits health check provided by the Pension Service.

3.21 The first phase of the programme was aimed both at pensioners and also households of all ages living in social housing. A major achievement of this phase was the provision of free central heating to all public sector tenants where they had not previously had central heating, and wanted it installed - 25,000 households in social housing received the package. This part of the programme is complete and attention is now focussed on pensioner households in the private sector.

3.22 The original intention of the programme was to tackle the energy efficiency aspect of fuel poverty by installing energy efficient heating and insulation in the homes of pensioners without central heating. Over time, eligibility for the scheme has

18 That is, depending on the nature of the property : loft, cavity wall, tank and pipe insulation and draught proofing.

28

gradually expanded with a mix of universal and means-tested entitlements and the programme now effectively has three sets of eligibility rules 19 . Any householder or their spouse living in private sector housing who conform to the following age/income requirements are currently eligible for the central heating package :

- Aged over 60 and have no central heating or a system broken beyond repair;

- (Introduced from May 2004) Aged over 80 who have a partial or inefficient system;

- (From January 2007) Aged 60-79, who receive the guarantee element of

Pension Credit and have a partial or inefficient system.

3.23 In 2006/07, 5,847 homes (57% of the overall central heating programme) benefited from the main (over 60s) programme; 3,982 homes (39%) received replacements under the over 80s programme; and 409 dwellings received replacements under the more recently introduced programme for 60-79 year olds in receipt of pension credit. Since the beginning of the programme in 2001, up to March

2008, nearly £300 m was spent by the Scottish Government installing central heating systems in nearly 100,000 homes in the private and public sector.

Targeting of the CHP

3.24 The Scottish Government’s commitment to tackle fuel poverty covers all household types in fuel poverty, however, our programmes are not specifically targeted on the fuel poor. Instead, the Central Heating Programme is targeted at the household type that is statistically most likely to be fuel poor – that is, pensioners.

Table 2 , which uses 2005/06 data from the SHCS, has shown that fuel poverty is much more prevalent in pensioner groups than in other household types. Nearly half

(47%) of single pensioners and 41% of “older, smaller” households are fuel poor.

The household type with the next highest incidence of fuel poverty is single adults, with the much lower rate of 24% 20 . It is clear that if resources are to be targeted on any particular household type, then pensioners are the most effective group to target, and it avoids issu es around “means-testing” that could follow from alternative methods of targeting. However, the end result is that it would be expected that more than half of the household group primarily benefiting from public expenditure on fuel poverty programmes is not actually fuel poor. At the same time, many household types that include significant numbers of fuel poor

– such as single adults and lone parents - are not eligible for the CHP (although such households do qualify for Warm

Deal (insulation) measures, if in receipt of certain benefits).

3.25 Figure 5 shows the proportion of those living in private sector homes (i.e. the sector targeted by the CHP) that are fuel poor, according to age. This indicates that pensioner households are more prone to fuel poverty, but not exclusively. Around half of pensioner households in private homes were estimated to be fuel poor in

2005-06, and just over a tenth of non-pensioner households. It also shows that amongst pensioner households, a larger proportion of over 80s are fuel poor (62%), compared to those between 60 and 80 (48%).

19 The element of the programme dealing with central heating in Glasgow Housing Association dwellings is now complete.

20 Source : SHCS, 2005-06

29

Figure 5: Relationship between Fuel Poverty and Age

– Proportion of

Households in Group that is Fuel Poor

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

25

51

11

48

62

All ages All over 60s < 60 60-79 80+

Source: Scottish Housing Condition Survey, 2005-06, Private households only

3.26 Figure 6 takes this a stage further and breaks down each group into those that are on a low income, defined here as the bottom two deciles, and those that are not. This indicates that there is a much closer correlation between low incomes and fuel poverty than between age and fuel poverty. Three-quarters of those in the bottom two deciles of income are fuel poor, whereas only half of the over 60s are fuel poor.

30

Figure 6: Relationship between Fuel Poverty and Household Income

–

Proportion of Households in Group that is Fuel Poor

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

77

15

57

6

88

32

94

47 inc om e inc om e inc ome inc ome

inc ome

All age s,

low s,

not

low age

All

<6

0,

low

0 not

<6

low

60

-7

9, low

60

-7

9, not

low

inc ome

80

+,

low

80 inc ome

+,

not

low inc ome

Source: Scottish Housing Condition Survey, 2005-06, Private households only. Low income defined as bottom two deciles.

3.27 Pensioners in Scotland are gradually becoming better off as measured by the official poverty statistics. In 1996-7, there were around 270,000 officially poor 21 pensioners in Scotland (31% of all pensioners). This had fallen to 220,000 (25%) by

2002-3 and has fallen further to about 160,000 (18% of all pensioners) by 2005-6.

This means that over the 9 years to 2005-6, the number of pensioners in poverty in

Scotland fell by around 40% due to such factors as the introduction of Pension

Credit.

22 Therefore, if such trends continue, the expectation would be that there would be downward pressure on the level of fuel poverty among pensioners as incomes increase making the targeting of pensioners as a group even less effective than at present.

Impact on fuel poverty

3.28 Table 6 provides illustrative comparative data on the effectiveness of the CHP and Warm Deal programmes in terms of energy efficiency, carbon saving and fuel poverty reduction. The impact of the schemes will vary according to the particular property and household affected. The data for this modelling exercise is based on a

3 bedroom semi-detached house in Edinburgh, which in many ways is typical for

Central Scotland. This shows that, in this example, first time installations under the

CHP have greater impact on energy efficiency and fuel poverty than replacements;

21 Poverty is defined as below 60% of median income after housing costs.

22 From Households Below Average Income Dataset (Department for Work and Pensions).

31

and that boiler-only replacement is more cost-effective than whole system replacements. While this example is illustrative only, it is based on contemporary data. Other more detailed, academic studies have also been undertaken to assess the impact of previous phases of the CHP.

Table 6: Comparison of effectiveness of different types of central heating provision

First time fitting of efficient central heating (house with no insulation, no central heating)

Thermal comfort (NHER scale 0-10)

Annual fuel bill (£)

Without

2.2

1,562

With

5.8

1,004

Change

3.6

-558

CO 2 emissions (tonnes)

Percentage of income spent on fuel

8.5

13.6

5.6

8.7

Replacement of inefficient central heating with efficient central heating

(house with no insulation, inefficient central heating)