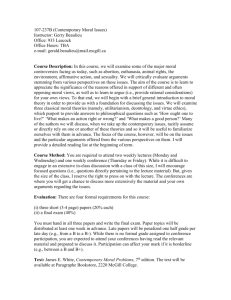

Particularism and Supervenience

advertisement