Individual Behaviour Change:Evidence in transport and public health

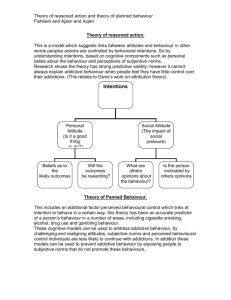

advertisement