2001 Annual report - NSW Coroner`s Court

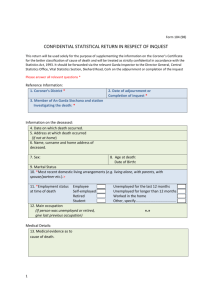

advertisement