The 1958 And 1970 Cohort Studies compared, Working

advertisement

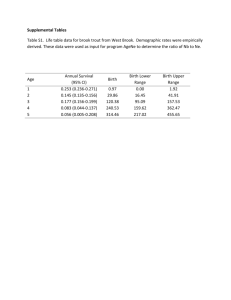

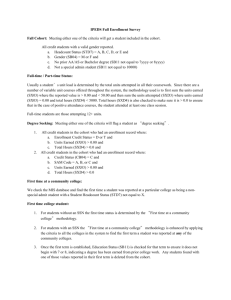

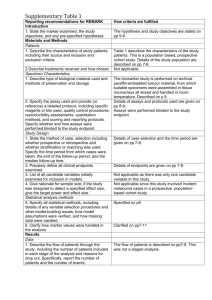

WORKING PAPER 2 DELAYED CHILDBEARING IN BRITAIN: THE 1958 AND 1970 COHORT STUDIES COMPARED. Roona Simpson Centre for Research on Families and Relationships Centre for Research on Families and Relationships University of Edinburgh 23 Buccleuch Place Edinburgh EH8 9LN. Email: Roona.Simpson@ed.ac.uk INTRODUCTION Fertility patterns have changed significantly in most European countries in recent decades; the postponement of first births in particular has been associated with smaller family sizes and increased childlessness, all of which contribute to overall fertility decline. There are a range of theoretical perspectives associated with fertility decline, and a number of factors proposed in the demographic and sociological literature to explain it1. Delayed childbearing has been identified with changes in education and employment in recent decades, particularly for women (see Kohler, Billari and Ortega 2002; Sobotka 2004), with several scholars suggesting that birth timing and spacing may be key strategies individuals adopt to reconcile work and family responsibilities (e.g. Brewster and Rindfuss 2000)2. There is a considerable body of empirical research demonstrating substantial differences in first birth timing by education level and labour market position (e.g. de Cooman, Ermisch and Joshi 1987; Joshi 2002). In addition, there is much debate in both the demographic and sociological literature about individualisation and the changing character of intimacy and partnership, and their relationship to fertility postponement and decline3. Interpreting statistics on changes in demographic behaviour in terms of changing individual motivations is problematic; however, partnership patterns are becoming more complex and diverse, and there is empirical research supporting ideas that changing partnership patterns are associated with late entry into parenthood (see Berrington 2004, Olah 2005)4. This paper reports the results of analysis conducted on the 1958 and 1970 British cohort studies. This analysis illustrates evidence of changes in the timing and extent of first birth amongst different cohorts in relation to various socio-economic 1 See Simpson (2006) Childbearing on Hold: a Literature Review for an overview of the key theories and determinants proposed in the literature. 2 Debates about the options available to individuals in reconciling work and family responsibilities include discussion of the social policy contexts in which these decisions are being made (see Gauthier 1996, Esping-Anderson 1999, Hobson and Olah 2006a, 2006b). 3 Several scholars have attributed various contemporary changes in family and household structures (such as the delay and decline in marriage, rising divorce rates, increasing cohabitation, and increasing periods of singleness) to shifts in societal norms and values, conceptualised broadly in the demographic literature as the Second Demographic Transition (see van der Kaa 1987; Lesthaeghe 1995) and associated with the Individualisation thesis within the sociological literature (see Giddens 1992; Beck and Beck-Gernsheim 1995). 4 These processes are inter-related, and changes in education and employment are associated with changes in the timing and type of partnership (see Oppenheimer 1998, 1994; Berrington and Diamond 2000; Berrington 2003). 1 characteristics such as social class background, educational attainment, and partnership status. Most research on fertility decline focuses on women, to the empirical neglect of men (Greene and Biddlecom, 2000:81)5. These cohort studies allow a comparison of the characteristics and circumstances of women and men remaining childless in their early thirties. As well as comparisons by sex, this intercohort analysis allows comparisons across time, thereby providing a picture of the impact of social change on the lives of cohort members. Those born in 1958 will have experienced their early adulthood during the 1980s, a very different political, social and economic context from those born in 1970: whereas the 1958 cohort initially experienced a buoyant labour market but faced worse conditions as they got older, the opposite occurred for those born in 1970. Rising living standards in recent decades have been accompanied by increasing polarisation in terms of wage inequality. Previous analyses of the cohort studies demonstrate changes across a range of domains such as education, employment, health and family life, which reflect the wider social context in which these changes were experienced (see Ferri et al, 2003). To illustrate, the expansion in further and higher education is evident in the increased acquisition of qualifications by both men and women (for example, the proportion of women with tertiary qualifications rose from a quarter of those born in 1958 to just under a third of the 1970 cohort), as well as the declining proportions leaving school at 16 (from 60% of 1958-born women to 45% of those born in 1970) (Makepeace et al., 2003). The focus of this paper is changes in the timing and propensity to have children, which are related to other changes over time in family and household composition; these are referred to throughout the paper. However, there is a complex relationship between wider social processes and changes at the family and household level. For example, a declining propensity to home ownership (less than two-thirds of the 1970 cohort buying their own home in their early thirties compared with four-fifths of the 1958-born cohort) in part reflects trends such as rising housing costs, however may also be linked to factors such as the increasing emphasis on educational qualifications 5 This may be in part due to the greater reliability of reported fertility by women. Previous research suggests some unreliability in men’s reporting of children, especially of non-marital births: for example Rendall et al (1999) in an evaluation of men’s retrospective fertility histories from the British Household Panel Study found only 60 of men’s births from a previous marriage were reported per 100 of women’s births, with women’s fertility reports matching birth registration statistics. 2 (Smith and Ferri, 2003). It is difficult to distinguish the relative impact of these processes on specific life events such as starting a family. It is beyond the scope of this paper to consider the extent to which wider social changes support or inhibit family formation, however the findings reported below should be considered in relation to the broader social context in which these are taking place. Data and Methods The National Child Development Study (NCDS) and British Cohort Study (BCS) are longitudinal surveys following a sample of individuals born between March 3-9 1958 and April 5-11 1970 respectively. Surveys to monitor the educational, physical and social development of these cohorts have taken place at varying intervals, with data collected at birth, 7, 11, 16, 23, 33 and 42 for the NCDS and at birth, 5, 16, 26 and 306 for the BCS. Full partnership and fertility histories were collected from the NCDS cohort at age 33 and from the BCS cohort at age 307. Longitudinal data enables the opportunity to investigate demographic events within a life course perspective however are subject to attrition, and approximately 70% of those taking part in the birth survey were interviewed in their early thirties. Previous analyses of the response bias arising from this suggests it is the most socio-economically disadvantaged and those from non-white backgrounds over-represented amongst those lost over time (for further detail see Shepherd 1995). Both samples also under-represent those who began child-bearing in their teens (Berrington 2003). There are 11,471 men and women aged 33 in the NCDS cohort, and 11,261 aged 30 in the BCS cohort. The analysis described in the section below compares the socioeconomic characteristics and circumstances of those who remain childless in their early thirties8. Comparisons are also made with those who have had children at the same age, to provide a broad overview. It illustrates differences between men and women, as well as changes over time between cohorts9. Cohort members remaining childless in their early thirties will have experienced this in somewhat differing 6 Excepting some respondents interviewed prior to April 2000 at age 29. These fertility histories were used in the survival analyses presented below, following cleaning the data to address those with missing/incomplete birth dates. Those giving birth before 16 (15 cases in the 1958 cohort) were excluded from analysis. 8 As the focus of this paper is on postponed fertility, it only considers biological children and childlessness is defined as not having had a live birth; those classified as childless may include respondents with adopted or step-children. 9 All figures cited are statistically significant (p< 0.05). 7 3 circumstances: those born in the late 1950s experienced this is in 1991, while those born in 1970 experienced this at the turn of the century (1999/2000). This research considered several variables identified as important in the literature10. As noted above, previous research has attributed fertility postponement to changes in education and employment (particularly for women), and partnership formation. However, these are mediated by social class (Berrington 2003). This paper reports the results of analyses looking at childlessness by sex in relation to social class background11, educational attainment12, current economic status, and current partnership status13. THE PROPENSITY TO CHILDLESSNESS AMONG YOUNG ADULTS DIFFERENCES BY SEX AND CHANGES OVER TIME - The following section compares the incidence of childlessness amongst cohort members at age 29, looking at both women and men. Childlessness by Sex As Chart 1 illustrates, there are significant differences by sex, with larger proportions of men remaining childless at age 29 compared with women in both cohorts. Thus, nearly half of men (47%) in the 1958 cohort remained childless at 29 compared to a third of women at the same age. For the 1970 cohort the figures were around three fifths (59%) of men and 45% of women at the same age. 10 Initial analysis was carried out looking at religiosity. The Second Demographic Transition attributes declining fertility to, inter alia, a growth of values of self-realisation and freedom from traditional forces of authority such as religion, while previous research reports a correlation between increased religious activity and more traditional attitudes to family (e.g. Berrington and Diamond 2000, Olah 2005). However, while there was a decline in religiosity evident (only 11% of the 1970-born cohort who defined themselves a having a religion attended services at least monthly, compared with 30% of the 1958 cohort), there was no significant association with childlessness. 11 Identified using the occupational social class (Registrar General’s definition) of the cohort member’s father (or father figure) at age 16. 12 Recoded into those with no qualifications, school-level qualifications (including A/S level and their NVQ equivalents) and tertiary level qualifications, which include Higher qualifications, degrees and NVQ equivalents (4-6). 13 Here, partnership is defined as co-residential, and results are reported for both marital and cohabiting relationships. The partnership histories record relationships in which respondents ‘lived with someone as a couple’ for a month or more. However, as Murphy (2000) observes, assuming all co-residential partnerships as equivalent raises several issues: these differ not just in de jure status, but in terms of the meanings and motivations these hold for respondents. 4 As these figures indicate, there have been considerable changes across time. Previous analysis of the cohort studies (Berrington 2003) finds an increase in the median age for first birth for women from 26 to 2914. These figures indicate a considerable increase in the proportion of adults remaining childless at 29 in just twelve years. Chart 1: Childlessness at 29, by Cohort and Sex (%) 70 Percentages 60 50 40 Men 30 20 59 47 45 Women 33 10 0 1958 1970 Birth Cohort Childlessness by Social Class Background This section looks at the occupational social class (Registrar General’s definition) of the cohort member’s father (or father figure) at the time of birth to identify the social background of cohort members. As Chart 2 illustrates, there are differences across social class differences in the propensity to remain childless at age 29. For example, for women born in 1958, 46% from professional or managerial backgrounds (I and II) were childless at 29, compared to 26% of those with fathers in semi-skilled and unskilled occupations (IV and V). While there has been an increase over time across the social classes, the patterns differ by sex: for example, men from professional or managerial backgrounds show the largest increase (13%, from 56% to 69%), whilst for women this category has increased the least (9%, from 46% to 55%). 14 While at the same time similar proportions (around 10%) became teenage mothers, indicating increasing polarisation between women in relation to age at first birth. 5 Chart 2: Childlessness at 29, by Social Class Background (%) I and II IIINM IIIM IV and V No Father Figure TOTAL 80 70 60 50 40 30 59 47 20 10 0 45 33 1958 Men 1970 1958 Women Birth Cohort and Sex 1970 Childlessness by Educational Attainment This section reports analysis comparing the incidence of childlessness by educational attainment amongst cohort members in their early thirties, at ages 33 for the NCDS and 30 for the BCS respectively. Recent decades have seen a massive expansion in post-secondary education, and young adults spend an increasing proportion of time in education. The 1958 cohort experienced an educational context in which the majority (over 60%) of young people left school at 16, however by the time the 1970 cohort reached 16, in 1986, this had declined to less than half (54% of males and 45% of females). The likelihood of remaining childless as a young adult is influenced by educational attainment15. There is considerable evidence from previous research of large differences in first birth timing according to levels of education (see Sobotka 2004), and there has been much attention to increases in women’s educational attainment in particular16. Nevertheless, as the analysis presented below illustrates, these differentials also hold for men. 15 There is much debate about the role of educational attainment and the extent to which this influences fertility decline directly and indirectly; for example, the time spent in education may be incompatible with starting a family (see Kohler, Billari and Ortega, 2002), however is also associated with changing values and preferences (Oppenheimer 1994). For further discussion see Simpson 2006. 16 However, as Makepeace et al. (2003) observe, this broad observation does not address continuities in the large differences by gender in subjects studied. Furthermore, their analysis of the cohort studies demonstrate that the gap in the chances of gaining tertiary qualifications for those from the highest and lowest social classes has widened steadily over time. 6 Table 1 presents figures for the proportion of men and women remaining childless in their early thirties. Differentials by educational attainment levels are significant for both men and women. Amongst childless women in the 1958 cohort, for example, the proportion of those with tertiary education (37%) is nearly three times that for those without qualifications (13%). These differences are similar, if not so extreme, for childless men. Looking at difference by sex, the largest differences are between men and women from the 1970 cohort with no qualifications: a third of these women remain childless compared with over half (53%) of unqualified men. Looking at changes over time, the largest increase has been amongst men with tertiary qualifications, a rise of 37% (from 41% to 78%). This compares with the largest increase for women in the same educational category, 31% (from 37% to 68%). Table 1: Childlessness by Educational Attainment, Early Thirties (%) Sex Birth Cohort MEN 1958 29 31 41 5453 1970 53 58 78 5450 WOMEN 1958 13 21 37 5687 1970 33 45 68 5773 No School Level Tertiary Qualifications Qualifications Qualifications Sample (100%) Chart 3: Childlessness by Educational Attainment, Early Thirties (%) 100 80 60 No Qualiications 40 School Level 20 Tertiary 0 Men Women 1958 Men Women 1970 Birth Cohort and Sex 7 Childlessness by Current Economic Activity Analysis was conducted to compare the proportions of men and women remaining childless in their early thirties by economic activity, as well as looking at changes over time. There has been much debate in the literature over the role of women’s employment in particular in fertility decline, with some commentators proposing women’s increased labour force participation as an indicator of increasing gender equality. Such claims however do not address factors such as hours of work or levels of pay (see Simpson 2006). Previous research by Makepeace et al. (2003) finds differences by sex in the proportions of men and women born in 1970 who experienced continuous employment between ages 16 to 30, 30% compared with 14% respectively. There is also an increasingly strong relationship between qualifications and continuous employment: in the 1970 cohort, highly qualified women are more likely to remain in continuous employment than both their less qualified contemporaries and their predecessors in the 1958 cohort (Makepeace et al, 2003:58). Preliminary analysis of the 1958 cohort’s economic activity showed significant differences in economic status by sex: 89% of all men were in full-time employment, compared with 36% women, of whom around another third, 32%, worked part-time or looked after the home and family (28%). Similar analysis on the 1970 cohort demonstrates considerable change in the economic activity of all women, with over half (51%) now in full-time employment and concomitant decreases in the proportions working either part-time (23%) or looking after home and family (19%). However, for men, there is little change in the proportions working full time (88%); in both cohorts the second largest category for men was unemployed (6% and 4% of the 1958 and 1970 cohorts respectively). Subsequent analyses considered the incidence of childlessness in relation to economic activity by parental status. Not surprisingly there were significant differences evident amongst women, for both cohorts. Amongst the 1958 cohort, the vast majority of childless women were in full-time employment, 82% compared to 22% of mothers. The picture for men was very different however, with a slightly higher proportion of fathers (90% compared with 88%) working full-time. Looking at the 1970 cohort indicates very little change over time – 80% of childless women worked full-time 8 compared with 22% of mothers. The figures for men had also not changed, with 88% of father and childless men working full-time. Thus, men are overwhelmingly in full-time employment, regardless of parental status. Interestingly, childless women from both cohorts are more likely to be categorised as either working part-time or looking after home and family (over 12%) than fathers of the same age (less than 3% in both cohorts). Previous findings indicate that British men have the highest average number of working hours compared with other men in the European Union, while British fathers work longer hours on average than men without dependent children (Kiernan, 1998). These figures suggest a lack of change in the retention of caring responsibilities by women compared with men, regardless of parental status. As well as providing a salutary caveat to optimistic claims of increasing gender equality, these findings suggest discrepancies in resources of time, a factor which Presser (2001) relates to fertility decline. The considerable changes in patterns of family formation in recent decades include not just dramatic changes in parenthood, but also partnership. These include a delay in forming first partnerships, a decline in marriage alongside an increase in both cohabitation and singleness, and an increase in relationship turnover17. These all have implications for the context of childbearing18. The following section illustrates the association between partnership status and the incidence of remaining childless. Childlessness by Partnership Status Previous analyses of the cohort studies have highlighted the dramatic decline in marriage: whereas three quarters of women and two thirds of men had married by age 29, just over half of women and a little over a third of men born in 1970 had done so (Berrington 2003). Some of the decline can be explained by an increase in cohabitation, and cohabitation was the most common form of first partnership for the 17 While in 1971 the average age of first marriage in England and Wales was 25 for men and 23 for women, by 2003 this had increased to 31 for men and 29 for women. Non-marital cohabitation amongst those under 60 in Great Britain doubled between 1986 (the earliest year for which data are available on a consistent basis) and 2004, from 11% to 24% for men, and 13% to 25% for women (ONS 2006). 18 Births by unmarried women accounted for 42% of all births in the United Kingdom in 2004, compared to an EU (15 countries) average of 33% (Eurostat 2006). Scotland had an even higher proportion with nearly half of all births (47% in 2004), a considerable increase on less than a third (31%) ten years previously (GROS, 2005). 9 1970 cohort (Berrington 2003). However, there is also an increase in the proportions who have never experienced any cohabiting partnership, as well as evidence of a delay in partnership, whether marriage or cohabiting. For example, women born in 1970 are also very much less likely to have entered their first partnership at a very young age: just over a quarter had lived with a partner by age 20, compared with 40% of women born in 1958 (Ferri et al. 2003). In addition, there is a rise in relationship dissolution, with twice as many men and women born in 1970 having been in at least one previous relationship by age 30 (Ferri et al. 2003). These changes indicate a concomitant increase in singleness, either prior to or between relationships. In terms of living arrangements, other research identifies a higher proportion of men in their early thirties either living alone (14% compared to 9% of women born in 1970) or living in the parental home (one in six men born in 1970, more than twice as many compared to women of the same age), and as such a greater decline in residential partnership amongst men (Ferri et al 2003). Analyses of the British Household Panel Survey notes an increasing tendency since the 1980s for young adults to return to the parental home (Ermisch and Francesconi, 2000). In part this may be related to changes such as the increase in partnership dissolution. However, this may also be associated with wider changes in areas such as housing or education, and indicate a delay in young adults establishing themselves as economically independent19. Preliminary analysis of the cohorts by legal marital status20 indicates a dramatic increase in the proportions remaining never-married over time, as well as significant differences by sex. A fifth (21%) of all men from the 1958 cohort remained nevermarried in their early thirties, compared to 14% of women of the same age. However this had increased to 57% and 44% of the 1970 cohort respectively. Differences between men and women may be explained in part by the fact that traditionally 19 Preliminary analyses of the cohort studies identify a significant decline in home ownership between the cohorts. Interestingly, slightly higher proportions of women born in 1970 compared to men were buying with a mortgage (62% versus 58%), a reversal of the situation for the 1958 cohort (75% women compared with 78% men). While the proportion living in social housing (housing associations or local authority) remained the same at about 15%, the proportions of those renting from other than social landlords had increased over time (from 6% to 21%) for the 1970 cohort, while the proportions classified as ‘living rent free’, including with parents, had also increased. 20 In both cohorts the relevant variables were recoded to identify those married (combining first or second marriages), those previously married (that is currently legally separated or divorced, as well as widowed, of whom there are very small numbers in each cohort), as well as the never-married. 10 women have tended to marry at younger ages than men. This category refers to the civic status of never having married, thus does not preclude those who may currently be cohabiting, hence the subsequent analysis reported below considers current partnership status which distinguishes those currently cohabiting, regardless of previous marital status. Table 2 provides figures for the proportions of men and women who remain childless at age 29 by partnership status. Given the changes in partnership formation noted previously, we might expect the significance of marital status to wane over time. Yet, despite changes such as an increase in cohabitation, an association between marriage and childbearing persists across time. For example, the proportion of childless men from the 1958 cohort ranges from 35% of the married to 97% of those never-married and currently single. Figures for childlessness amongst women of the same age range from a quarter of married women to 83% of the never-married. There has been a slight decrease over time, nevertheless figures for the 1970 cohort show these differentials by partnership status persist. Looking at changes over time, childlessness appears to have increased amongst married and cohabiting women (by 5% and 6% respectively) but not men of the same status. Childlessness has risen amongst the previously married by 11% for both sexes however, from 37% to 48% of previously married men and 24% to 35% of previously married women. Table 2: Childlessness by Partnership Status at age 29 (%) Sex Birth Cohort Married Cohabiting Single NeverMarried Previously Married Sample (100%) MEN 1958 35 62 97 37 5543 1970 35 61 90 48 5376 WOMEN 1958 25 48 83 24 5767 1970 30 54 72 35 5761 Charts 4 and 5 below illustrate these changes graphically, showing the relative decline in childlessness as cohort members’ age. Charts 4a and 4b look at those born in 1958 up to age 33, and it can be seen that the proportions of childless married decline considerably for both sexes between 29 and 33, to 17% of married men and 13% of 11 married women. There is also a continuing decline in childlessness for those cohabiting, to 50% of men and 40% of women. The decline for other categories between the ages of 29 and 33 is more gradual. Chart 4a: Childlessness by Partnership Status amongst Men, 1958 Cohort Married Cohabiting Single Never-Married Previously Married 100% 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Chart 4b: Childlessness by Partnership Status amongst Women, 1958 Cohort Married Cohabiting Single Never-Married Previously Married 100% 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Charts 5a and 5b below compare the proportions remaining childless in the 1970 cohort. Comparing these charts, the delay and decline in childbearing across cohorts up to age 29 is evident. However we do not yet know what this cohort will do in the future, and these figures suggest the importance of comparing cohorts at later ages to see whether there is an overall increase in the propensity to childlessness. 12 Chart 5a: Childlessness by Partnership Status amongst Men, 1970 Cohort Married Cohabiting Single Never-Married Previously Married 100% 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Chart 5b: Childlessness by Partnership Status amongst Women, 1970 Cohort Married Cohabiting Single Never-Married Previously Married 100% 80% 60% 40% 20% 0% 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 The persistent differences by partnership status suggest the pace of shifts in the context of childbearing (within marriage) lag behind shifts in partnership formation, a finding which has implications for future fertility patterns. The decline in marriage may herald a shift to cohabitation, while the delay in partnership may reflect postponement rather than overall decline21. However, there is considerable evidence that cohabitation is a more fragile relationship than marriage, and that divorce is more common in marriages preceded by cohabitation (e.g. Haskey 1992, Ermisch and Francesconi 1996). Previous research on the 1958 cohort (Berrington and Diamond 21 Berrington (2003) suggests broadly similar proportions of men and women do go on to partner by age 29. Other analyses indicates that of those born in 1958, the great majority (about 8 out of 10 men and women) were living with a partner at age 42 (Ferri et al. 2003). 13 2000) suggests that experience of independent living prior to partnership formation is associated with a preference for cohabitation rather than direct marriage, and higher separation rates amongst cohabiters. Relationship stability is related to both timing and type of relationship; this suggests that current patterns of fertility decline are unlikely to alter in the future, given trends in partnership formation and dissolution and the association of childbearing and marriage identified above. CONCLUDING REMARKS This preliminary investigation into delayed childbirth identifies associations between delayed childbirth and various socio-economic factors, and highlights the need for further research. While there is much attention in the sociological and demographic literature on fertility decline to notions of increasing individualisation and values of personal autonomy (see Simpson 2006), this analysis indicates structural factors influencing the incidence of childbirth, with consistent differences by social class background evident across the cohorts. The analysis also identified differences by factors such as educational attainment across cohorts. Differences between men and women in relation to economic activity, including between childless women and all men indicate the importance of gender over parental status in shaping work practices. These figures also suggest claims of gender equality based on labour market participation are somewhat over-optimistic. Inter-cohort comparisons presented in this paper identify a delay in childbearing in the context of increasingly diverse partnership patterns. Nevertheless, childbirth remains associated with being ever-married. These findings suggest the importance of research investigating changes in partnership formation as a precursor to fertility decline. The gendered nature of shifts in partnership is striking. There is little contemporary research on singleness for men22. However, the association of singleness with childlessness demonstrated here suggests the need for further research encompassing a gendered analysis of changes in partnership formation more generally, and the propensity to singleness in particular, in order to get a fuller picture of the processes underlying delayed childbirth. 22 Until recently there has been relatively little research on singleness, however the past few years has seen an increase in both historical research and research on contemporary singleness for women (see Simpson 2005 for an overview). 14 REFERENCES Beck, U. and Beck-Gernsheim, E. (1995) The Normal Chaos of Love, Oxford: Polity Press Berrington, A. (2003) Change and Continuity in Family Formation among Young Adults in Britain, SSRC Working Paper A03/04, University of Southampton. Berrington, A. (2004) ‘Perpetual Postponers? Women, Men’s and Couple’s fertility Intentiona and Subsequent Fertility Behaviour’, Population Trends 117, Autumn. Berrington, A. and Diamond, I (2000) ‘Marriage or Cohabitation: a competing risks analysis of first-partnership formation amongst the 1958 British birth cohort’, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 163: 127-151. Brewster, K. L. and R. R. Rindfuss. 2000. “Fertility and women's Employment in Industrialize d Nations, Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 271-96. De Cooman, E., J. Ermisch, and H. Joshi. 1987. “The next birth and the labour market: A dynamic model of births in England and Wales”. Population Studies 41 (2): 237-268. Esping-Andersen, G. 1999. Social foundations of postindustrial economies. Oxford University Press, Oxford. European Commission (2006) Eurostat Total Fertility Rate Indicators, http://epp.eurostat.cec.eu.int/portal/page?_pageid=1996,39140985&_dad=portal&_schem a=PORTAL&screen=detailref&language=en&product=sdi_as&root=sdi_as/sdi_as/sdi_as _dem/sdi_as1210 Ferri, E. , Bynner, J. and Wadsworth, M. (eds.) 2003. Changing Britain, Changing Lives: Three Generations At The Turn Of The Century, London : Institute of Education, University of London Gauthier, A. H. 1996. The State And The Family. A Comparative Analysis Of Family Policies In Industrialized Countries. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Giddens, A. 1992. The Transformation Of Intimacy. Sexuality, Love & Eroticism In Modern Societies. Polity Press, Cambridge. Greene, M. and Biddlecom, A.. (2000) “Absent and Problematic men: Demographic Accounts of Male Reproductive Roles”, Population and Development Review 26(1), March 2000, pp:81-115 GROS (2005) ‘Scotland's Population 2004 - The Registrar General's Annual Review of Demographic Trends’, General Register Office for Scotland, http://www.groscotland.gov.uk 15 Hobson, B. and Olah, L. Sz. (2006a) ‘BirthStrikes?: Agency and Capabilities in the Reconciliation of Employment and Family’, Marriage and Family Review, No. 39, The Haworth Press Hobson, B. and Olah, L. Sz. (2006b), ‘The Positive Turn or BirthStrikes?: Sites of Resistance to Residual Male Breadwinner Societies and to Welfare State Restructuring’, Recherche et Previsions no.83 (March), Special Issue: Kind and Welfare State. Reforms of Family Policies in Europe and North America, CNAF Joshi, H. 2002 Production, Reproduction And Education: Women, Children And Work In Contemporary Britain,. Population and Development Review 28, 3, 445-474. Kiernan, K. (1998) ‘Parenthood and Family Life in the United Kingdom’, Review of Population and Social Policy, No.7, pp:63-81 Kohler, H.-P., F. C. Billari, and J. A. Ortega. 2002. “The emergence of lowest-low fertility in Europe during the 1990s”. Population and Development Review 28 (4): 641-680. Makepeace, G. Dolton, P., Woods, L., Joshi, H, and Galinda-Rueda, F. (2003) ‘From School to the Labour Market’ , in Ferri, E., Bynner, J. and Wadsworth, M. (eds.) Changing Britain, Changing Live, London: Institute of Education Lesthaeghe, R. 1995. “The second demographic transition in Western countries: An interpretation”. In.: K. O. Mason and A.-M. Jensen (eds.) Gender and family change in industrialized countries. Oxford, Clarendon Press, pp. 17-62. Murphy, M.(2000) 'The Evolution of Cohabitation in Britain, 1960-1995. Population Studies 54, no. 1 Oláh, Livia Sz. (2005) ‘First childbearing at higher ages in Sweden and Hungary: a gender approach’, paper presented at the 15th Nordic Demographic Symposium, Aalborg University, Denmark, 28 – 30 April 2005 Oppenheimer, V.K. 1988. "A Theory of Marriage Timing." American Journal of Sociology 94:563-91 Oppenheimer, V. K. 1994. ‘Women’s Rising Employment and the future of the family in industrialised societies’, Population and Development review, 20:2, 293-342. Presser, H. (2001) ‘Comment: A Gender Perspective for Understanding Low Fertility in Post-transitional Societies’, Population and Development Review, Vol. 27, pp.177183. Simpson, R. (2005) Contemporary Spinsterhood in Britain: Gender, Partnership Status and Social Change, unpublished PhD thesis, University of London. Simpson, R. (2006) Childbearing on Hold: A Literature Review, Working Paper 1, available at: http://www.uptap.net/project05.html 16 Smith, K. and Ferri, E. (2003) ‘Housing’, in Ferri, E. , Bynner, J. and Wadsworth, M. (eds.) 2003. Changing Britain, Changing Lives, London: Institute of Education Sobotka, T. 2004. Postponement of Childbearing and Low Fertility in Europe, PhD thesis, University of Groningen. Dutch University Press, Amsterdam, 298 pp. Van de Kaa, D. J. 1987. “Europe’s second demographic transition”. Population Bulletin 42 (1). 17