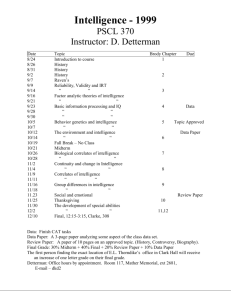

MAYBE NeedTheoryIntel

advertisement