The Jews in Eretz-Israel/Palestine, From Traditional

advertisement

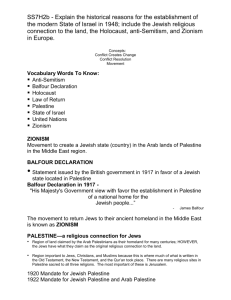

Kark, Ruth and Glass, Joseph. B. “The Jews in Eretz-Israel/Palestine, From Traditional Peripherality to Modern Centrality.” Israel Affairs 5/4 (Summer 1999): 73-107. See Also In Israel: The First Hundred Years Vol 1, Israel's Transition from Community to State. Ed. E. Karsh. London: Frank Cass Publishers, 1999. Introduction We open with a brief note on the state of research. Until about three decades ago most of the research conducted and published on the Jews in Eretz-Israel in the nineteenth and half of the twentieth centuries, might be considered as being characterized by a “Judeo-Palestino-centrist” orientation. Initiated mainly by traditional historians of the Jewish people, economic historians, sociologists, political scientists, and geographers it restricted its focus only on the Jewish sector of the population, and dealt mostly with the changing ideological trends, ties with Diaspora Jewry, and local Ashkenazi community frameworks, interactions and conflicts. Even when choosing the Jewish Yishuv in Palestine as a unit of analysis, topics such as the traits and role of Sephardi and Oriental communities, the status and contribution of women in the different communities, urban and rural planning and architecture, were barely touched upon. The traditional schools of scholars did not consider the Jewish Yishuv in Palestine within a more general and comparative context as part of the Middle East in the period under discussion, nor did they attempt to interface their studies with general theories, models and paradigms. Themes and processes such as the influence of external political systems, or the comprehensive policy of the rulers (being in our case the Ottoman Empire and the British Mandate), westernization, colonialism and colonization, world and regional economic and technological change, environmental, spatial and physical change, and general processes of demographic, social and cultural change, were considered only in a very narrow context. Some of these spheres were dealt with by Middle East historians, who in their turn were criticized as an “Orientalist” school and unqualified to gain full understanding of these processes and of the indigenous society. In Palestine itself the Arab sector of the population was viewed as one side of a dual society and economy, and conveniently put aside, unless it had to do with conflict and clashes between Jews and Arabs. During the 1950s and 1960s geographers 2 emphasized the regional paradigm. Consideration of the historical background of the areas studied was sketchy and minor. Those among the newer generation of Jewish-Israeli historical geographers that focused on study of the Jewish agricultural settlement in Palestine concluded that it was a type of colonization, and not a colonialist process or ethnic colonialism, as asserted by some so-called “new” historians and sociologists. The “Old School” of Jewish researchers of Eretz-Israel in the modern era described above was, and remains to some extent today, influenced pretty much, as Barnai showed, by myths, apologetics and ideologies (“enlightenment”, nationalism, Zionism), and among sociologists as Svirsky hinted, by the approach of retrospective analysis which studies the past in order to understand the building blocks of the present. A recent school of “post Zionist” historians of Eretz-Israel and the Yishuv developed according to Penslar and Bartal, as early as 1967. It was the beginning of a rift between the historians and Zionist ideology, and the detachment of scientific and critical research from the influences of national needs and ideology. The centrality of Eretz-Israel in the history of the Jewish People was questioned, the background to the pre-Zionist Aliyot ceased being part of the Zionist context, and the presence of a second nation became a legitimate topic of study instead of a sensitive political problem. Penslar and Bartal assert that historians of the national-religious camp, however, have adopted the Zionist narrative and under academic cover reintroduced myth into historiography. We set several objectives in writing this paper: To present a longitudinal narrative overview of the Jews of Eretz-Israel/Palestine (the Yishuv) during the late Ottoman and the Mandate periods. To consider the Jews of Palestine within the context of external political systems and the Jewish diaspora on one hand, and the local host society on the other. To provide a generalized dynamic typology of the demographic, political, social, cultural, spatial, and economic components over time. To refine the existing categorization of “old” and “New” Yishuv. 2 3 To further examine the contribution of Sephardi and Oriental versus Ashkenazi Jews to the growth and development of the Yishuv, which in our opinion has been underestimated. Certain aspects such as the status and role of women, and characteristics of several ethnic groups in the Yishuv require a more indepth attention then can be attempted in this framework. Government and Administrative Division Under Ottoman rule (1517-1917) there was no political entity actually known as Palestine but a term preserved by the Christian world referring to the “Holy Land” or “Judea”. The name taken from the Hebrew word Pleshet was used by Emperor Hadrian in an attempt to eradicate any trace of Judaism in the land. By the 425, the Byzantine heirs to the eastern part of the Roman Empire delineated three provinces: Palaestina Prima, which included the coastal towns, the Judean Hills and the Jewish section of the Jordan Rift; Palaestina Secunda, which comprised the Jezreel Valley, the Galilee, and the Golan; and Palaestina Tertia, which consisted of the Negev, Ammon, Moab and Edom. After the Arab conquest in 638, Palaestina Prima was named Jund Filistin. Under the Mamluke (1267-1517) and Ottoman rule, the use of the term Filistin was not resumed. Instead, Ottoman jurisdiction divided the territory between the provinces (vilayets) of Sidon (later Beirut) and Damascus. The latter controlled the northern sections of the area east of the Jordan River. Under the 1864 Law of Vilayets the districts (sanjaks) of Jerusalem, Nablus, and Gaza became a separate administrative unit, called the mutasariflik of Jerusalem. In 1873 its rule was transferred directly to Istanbul. In 1906 an administrative boundary was drawn between Sinai and the Ottoman Empire along the Rafah-Taba line. In 1908 the Negev was placed under the Governor of the Damascus province. The British gained control of Palestine during 1917 and 1918. On April 24, 1920 the Supreme Council of the Peace Conference at San Remo conferred the Mandate over Palestine on Great Britain. The British opted for the name Palestine in line with the European Christian tradition. As a concession to Jews who wanted the historic name Eretz Israel (Heb: Land of Israel), the initials aleph and yud were added in parentheses to the Hebrew form of the name of Palestine. The territory east of 3 4 the Jordan and Arava Valleys was separated and the protectorate of Transjordan was created in 1923 with Emir Abdullah ibn Hussein as its sovereign. The northern boundary of the area west of the Jordan River was finally determined in the spring of 1923. The area of Mandatory Western Palestine was 27,009 square kilometers (10,429 square miles) including 704 square kilometers (272 square miles) of inland water. The events of the 1948 war between the Jews and the Arabs divided Palestine with the newly founded State of Israel occupying 20,700 square kilometers (7,993 square miles). The Hashimite Kingdom of Jordan annexed the West Bank including East Jerusalem and the Kingdom of Egypt occupied the Gaza Strip. The territory consists of three major longitudinal strips. East of the Mediterranean Sea is the coastal plain which narrows from 40 kilometers in the latitude of Gaza in the south to 4-5 kilometers in the north near Rosh Hanikra. Inland the territory consists of a chain of mountains interrupted by latitudinal valleys. In the south are the Negev Hills. The Beer Sheva Depression separates them from the central mountain district (Judaean and Samarian Mountains). The Judaean Mountains peak at an elevation of just over 1,000 meters above sea level in the areas of Hebron and Ramallah. In the north is the Galilee, another mountain area separated from the chain by the Jezreel and Beit Shean Valleys. The northern boundary of this geographic region is Lebanon’s Litani River. The highest peak is Mount Meron (1,208 meters). The third strip is part of the Great Rift Valley. The northern section is defined by the Jordan River Valley including the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea. The elevation drops to 400 meters below sea level. The southern section, the Arava Valley extends to the Gulf of Eilat (or Aqaba) an extension of the Red Sea. The climate of most of the area is Mediterranean, characterized by winter rains and summer drought. This is typical of regions on or near the west coasts of continents approximately between the latitudes of 25 to 35. Precipitation reaches a maximum annual average of 1,100 millimeters in the Upper Galilee with averages of 625 millimeters for Haifa, 550 for Tel Aviv, and 500 for Jerusalem. An arid zone is found in the southern section of the country and is part of the global desert belt which included the Sahara and Arabian Deserts. In addition, the southern part of the Jordan Valley is arid 4 5 resulting from the rainshadow effect of the adjacent hills. The climate greatly affected human usage. The 300-400 millimeter isohyet was the approximate boundary of human settlement except where groundwater was available or run-off was collected. Beer Sheva receives annual average of 200 millimeters of rainfall and Eilat only 30 millimeters. The arid and semi-arid areas were traditionally inhabited by a nomadic population - the Bedouins. Change of Rule Seventeen-ninety-nine will be our starting point. It was then that Napoleon’s army invaded Palestine. What ensued was a new era in the history of Palestine. From a forsaken province, it became the focal point of a tug-of-war between the European powers and later Zionist efforts for the establishment of a homeland for the Jews. From a political and administrative perspective, the history of Palestine could be differentiated between: Ottoman rule (1799-1917) and British rule (1917-1948). Ottoman rule could be divided into four political sub-periods: 1) the period of Pashas - strong local rulers (1799-1831), i.e. a continuation of the eighteen century and the forms of government common then; 2) the conquest of Syria and Palestine by Egyptian ruler Muhammed Ali via his son, Ibrahim Pasha (1831-1840); in many respects this was a turning point, for despite the brevity of this period, the changes in government and other spheres were many; 3) the period of reforms (18411876), when Ottomans returned to power and tried to institute new patterns of government; 4) the end of the Ottoman period (1877-1917). The first and larger half of this period was marked by centralized rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid II; then came the rise of the Young Turks, who staged a revolution in 1908 and remained in power until the British occupation of Palestine in 1917-1918. The awakening of Palestinian nationalist sentiments began during the years preceding the war. This periodization has meaning vis-a-vis improving the status and security of Jews, Christians and foreign subjects. The rights of foreign nationals, which were mostly Jews, to own land throughout the Empire were revised in 1858 and 1867. However, in the last sub-period, laws and orders restricting Jewish immigration and land purchase in Palestine were issued. They were more strictly enforced from 1897 - the founding of the Zionist movement - to the First World War. 5 6 British rule has been sub-divided by researchers mainly according to criteria connected to the history of the Jewish population i.e. aliyah (waves of immigration), Jewish economic activity, or British activities vis-a-vis Jewish immigration and settlement, the Arab revolt and conflict with the Jews. The periodization from the perspective of the host society opened with the early years after the war (1918-1921) which saw the rise of Arab nationalism. Palestine was seen as part of “Southern Syria” and they demanded its incorporation into a large Arab state. This in many ways was a reaction to the Balfour Declaration (1917), a letter of intent from his Majesty’s Government for the establishment of a homeland for the Jews in Palestine. The second period (1922-1928) was that of appeasement. The Churchill White Paper calmed Arab fears of a Jewish state. This was followed by renewed nationalism (1929-1939) and the demands for a continued Arab majority. It peaked in 19361939 with the Arab Revolt which was expressed through general strikes and armed conflict against British authority and the Jewish population. The final period was that of conflict (1940-1948) with attempts at Arab appeasement during the world war to prevent their alliance with Germany. The exiled Mufti of Jerusalem Haj Amin el-Husseini set the tone and allied himself with Adolf Hitler. As well Jewish pressure mounted for increased immigration and territorial control during and following the war. It ended with the establishment of the State of Israel and the occupation of remaining sections of Palestine by Egypt and Jordan. The Communities of Palestine Palestine was populated by a mix of different peoples. The division may be drawn along religious or ethnic lines. However, until 1922 when the first comprehensive census of the area’s population was conducted information is based on incomplete data and conflicting estimates which are not always objective. In 1800, the population stood at an estimated of 250,000-300,000 (including about 5,500 Jews). Researcher Ben-Arieh basing his estimate on Western sources placed the total population at approximately 350,000 in 700 settlements in the early 1870s including 18,000 Jews (27,000 in 1880). To this we have to add about 25,000 Bedouins. According to Scholch’s estimate Palestine had some 470,000 inhabitants in 1882 (24,000 Jews). On the eve of World War I, 6 7 the population stood according to Schmelz’s new demographic study around 800,000 (and not 689,000) of which 85,000 were Jews (60,000 according to McCarthy). The population consisted predominantly of Sunni Muslim Arabs throughout the Ottoman period. Its growth in the nineteenth century resulted from a slow natural increase together with the migrations of small groups of Muslims mainly from other part of the Ottoman Empire. Egyptians settled in parts of the country under Mohammed Ali’s rule (1831-1840). Small groups of Muslim Bosnians, Algerians, Lebanese, Circassians and Turkomans also settled in Palestine. Part of this migration resulted from resettlement of loyal Muslim subjects who had been displaced by the loss of European territory on the fringes of the Ottoman Empire. Kemal H. Karpat estimated that 1.1 million Circassians were resettled in the Ottoman Empire, mostly in Anatolia, some in Syria including the Golan Heights, Transjordan, and a small number in northern Palestine. Some Metuwalis (Shiites) lived in villages near the border with Lebanon. A small Druze minority resided in villages on the Mount Carmel ridge and the Galilee. Under Ottoman and later British rule the community was not recognized as a separate community. Thus they were refused juridical autonomy and were subject to Muslim court procedure. Samaritans were found in the town of Nablus. A few Kararite families resided mainly in Jerusalem. Other religious groups gained a foothold in Palestine in the twentieth century including Bahais in the vicinity of Acre and Haifa and Ahmedis in Haifa. The Christian population was divided into a number of communities: Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Maronite, Syrian Orthodox (or Jacobite), Copts, and Ethiopian. The Ottoman regime recognized the Greek Orthodox and Armenian communities (and the Jews) as separate millets, religious communities organized around the political-religious authority of its spiritual leader. Protestant churches entered the scene in the early nineteenth century with some engaging in missionary activity mainly among other Christian sects and the Jewish population. Small groups of European and American Protestants even established agricultural settlements and urban neighborhoods, most noteworthy were the German Templers who founded several successful 7 8 settlements in Palestine from the late 1860s onwards. The Protestant activity had a profound effect on the population of Palestine, introducing Western ideas and technologies and improving health, social, and educational standards. Waves of Jewish migration from North Africa and the Middle East were one factor in the Jewish population growth. Eastern European Jews augmented the number; some settling for traditional reasons in the Holy Land and others following 1882 as part of the Hibbat Zion (Love of Zion) and Zionist enterprise. World War I (1914-1918) had a negative effect on Palestine. The area was placed under the virtual dictatorship of Jamal Pasha who expelled foreign Jewish nationals as well as local Muslim and Christian Arab leaders and families. Local Arabs and Jews were conscripted. To the financial and economic hardships caused by the war and aggravated by the corruption or the caprice of Turkish officials were added the outbreak of serious epidemics among the very helpless and underfed townsfolk and the invasion of swarms of locusts twice during the war. The front moved through Palestine with Jerusalem falling to the British in December 1917, and the north in the fall of 1918. Following the war the situation in Palestine improved with better health services and economic conditions. Among Muslims infant mortality dropped from 193.6 per thousand (19281930) to 135.3 per thousand (1940-1943). For the Jewish population there was a decrease from 84 per thousand to 55.6 per thousand for the same period. Life expectancy also improved greatly. Between 1926-1927 and 1940-1941 nine years were added to the average life span which a Jew might expect to live (63 years) and nearly eleven years to the average life of a Muslim (48 years). Muslim immigration to Palestine continued mainly from adjoining countries - Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, and Transjordan - in pursuit of economic opportunity. These immigrants constituted two or three percent of the total Arab population. Immigration played a more substantial role in the increase of the Jewish community. The population of Palestine increased by 923,00 between 1922-1943 with 62% from natural increase and 38% from net immigration. The non-Jewish population grew by 503,000 for the same period with 93% from natural increase. 75% of the Jewish growth was from net 8 9 immigration. As a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, part of the Arab population was displaced, some fleeing and others forced out. In 1949 140,000 Arabs became a minority under Israeli rule Yossi check here (See Table 1). Regarding the spatial distribution of the population of Palestine in 1800, it was predominately rural, about one-sixth of the population (54,000) resided in the twelve large towns. (Jerusalem 9,000, Acre 8,000, Gaza 8,000, Nablus 7,500, Safed 5,500). This urban population increased to some 120,000 at the end of the 1870s (Jerusalem 30,000, Gaza 19,000, Nablus 12,500, Hebron and Jaffa 10,000). By 1922 the population of these towns had reached 228,600 or approximately one third of the population. There was also a significant nomadic population. Bedouins roamed the Negev, the Jordan Valley, the Jezreel Valley and sections of the coastal plain. Expansion of the rural population into peripheral areas where settlement had not been possible before paralleled the partial retreat of the Bedouin population. Competition with settlers and entrepreneurs from outside Palestine served to further limit Bedouin control over sections of the country. Ottoman authorities checked their movement particularly from the 1870s onward. In 1931, there were 66,553 Bedouins with over twothirds in the Negev (Beer Sheva sub-district). Yossi check here (See Map 1) During British rule there was a further shift to the towns and cities. In 1945, 49 percent of the country’s population was urban although there were variations among the religious groups (for Muslims 30%, Christians 80% and Jews 74%). A number of factors brought about this urbanization: rural-urban migration due to increased pressure on agricultural land, the need for industrial workers in the cities, superior health services, and the attraction to other amenities found in the city. The Jews of Palestine From Homogeneity to Heterogeneity: Changes in Ethnic Composition and Spatial Patterns The Jewish population of Palestine differed from other Middle Eastern and North African Jewish communities in that they resided in a land of deep religious and ideological significance to Jews. The Holy Land offered the opportunity to be interred in its sacred soil and other forms of 9 10 religious fulfillment. It is believed that in the days of Messianic redemption the Jewish people will be in gathered from the four corners of the earth to Eretz Israel. Jewish liturgy repeats the hope of “Next Year in Jerusalem.” Another difference was the growing heterogeneity of Jewish Edot (ethnic groups) and communities, each with its own language, lifestyle, culture, religious modes and organizational frameworks. In the late nineteenth century Zionism took off as a significant force in attracting Jewish settlement and financial support. The Jewish population which did not exceed 5,000-6,000 in 1800 consisted of mainly Sephardi Jews exiles and their descendants from Spain and Portugal reaching Palestine via southern Europe, the Ottoman Empire and North Africa. European immigrants arrived in small waves. Hasidim came during the second half of the eighteenth century settling in the Galilee towns of Tiberias and Safed. A wave of Perushim (disciples of R. Elijah, the gaon of Vilna) began to arrive in the beginning of the nineteenth century. Prior to the middle of the nineteenth century the Jews of the “Old Yishuv” (see below) lived almost exclusively in the four ‘Holy Cities’: Jerusalem, Hebron, Tiberias and Safed. Their main center was in the Galilee towns. The focus moved to Jerusalem during Muhammed Ali’s rule in the 1830s. An event that contributed to that development was a major earthquake (1837) which killed thousands of Jews in Safed and Tiberias. Many survivors migrated to Jerusalem. The Jewish community of Jerusalem grew from a total of 3,000 (17% Ashkenazim) in the 1830s to 15,000, with over fifty percent Ashkenazim from 1883 and onwards. Since the middle of the century and onwards, Jews were pioneers in building neighborhoods outside the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. This process arose largely from a desire to overcome or escape from overcrowding, poverty, epidemics and the deteriorating infrastructure. The founders of the neighborhoods issued by-laws based on a mixture of Jewish legal tradition and modern concepts planning. The physical, economic and especially social neighborhood planning embodied in these guidelines, were quite advanced compared to prevailing European, American, and, no doubt, Ottoman towns of the same period. Parfitt argues, with much justification, that the “Old Yishuv” played in the years 1800-1880, a much more central role in the creation of a Jewish entity in Palestine 10 11 than has hitherto been recognized, that Jewish migration started long before Zionism, and that many social, demographic and institutional phenomena, which were to be important later, had their beginning during this rather neglected period. The pogroms in Russia in 1881 opened a new period for Jews in Palestine. The mass exodus of Jews from Eastern Europe resulted in the migration of some 25,000 to Palestine over the following two decades. The years 1882-1903 are known the “First Aliyah” (wave of immigration), characterized as the beginning of the Jewish agricultural settlement and proto-Zionist activity. However, the majority of the immigrants joined the orthodox population in the towns. Immigrants also arrived from Yemen and other Muslim countries. The “Second Aliyah” (1904-1914) saw approximately 40,000 immigrants, mainly from Eastern Europe. This strengthened the change in the balance in the composition of the Jewish community, with Ashkenazim becoming the majority. Jaffa which was a tiny walled port city with less than 3,000 inhabitants with a few Jews at the beginning of the nineteenth century, grew dramatically from the 1880s, as a center for the “New Yishuv” (see below). As a town characterized by a cosmopolitan, secular, nationalist spirit, served to balance the more parochial tradition-bound Jerusalem community. By the eve of World War I, Jaffa had grown to become the second largest city in Palestine after Jerusalem (50,000 including 15,000 Jews compared to Jerusalem - 75,000 and 53,800 Jews). It was then that the foundation was laid for its rank as primate city. In 1909 the founding by Ahuzat Bayit Society of a modern Jewish quarter north of Jaffa became the nucleus of the first Hebrew city in Palestine. Tel Aviv grew rapidly (1,500 in 1914, 46,301 in 1931, and 250,000 in 1948) to become the center of the main metropolitan area in Israel. Haifa, and Haifa Bay also developed during the twentieth century into an important center of the “New Yishuv” and the Labor Movements, as well as an economic core and foreland of Britain in Palestine and the Middle East Yossi check (See Table 2). Following World War I two factors, natural increase and immigration brought about a rapid growth in the Jewish population. Between 1922 and 1945 the natural increase was approximately 11 12 two percent per annum. An important factor was the improvement in health services which was expressed in a drop in infant mortality and the decline in the crude death rate from 12 per thousand in 1922 to 7 per thousand in 1945. The birth rate fluctuated around the 30 per thousand mark throughout this period. 359,066 Jews arrived in Palestine between 1919 and 1945. Their citizenship was Poland 40.9%, Germany 11.7%, U.S.S.R. 9.2%, Rumania 6.3%, Yemen 4.3%. British restrictions on Jewish immigration were circumvented through illegal immigration, with an estimated 25,000 tourists and illegal immigrants entering before World War II and over 12,000 illegal immigrants arriving during the war. After World War II and the holocaust there were attempts to bring Jewish displaced persons (sherit ha-plitah) from Europe to Palestine. Despite British restrictions 120,000 Jews entered Palestine during 1945-1948. 50,000 illegal Jewish immigrants were expelled by the British to Cyprus in 1946-48. Following the establishment of an independent state, the Jewish population was greatly transformed with a mass influx of Jews from the Middle East , North Africa and Soviet satellite states. The Jewish population of Israel almost doubled from 716,700 in November 1948 to 1,404,400 in December 1951. This resulted in the rapid decline in the Jewish population of certain Arab countries and a significant change in the percent of Asian-African-born Jews among foreign-born Jews in Israel, increasing from 15.1 percent to 37.0 in the span of just over three years (See Tables 2 and 3). Management Frameworks Under Ottoman rule, the millet system gave non-Muslim communities autonomy to organize their internal affairs. Minority prominent community leaders served as spokesmen to the Sultan who in turn by firman (Imperial order) exercised broad authority over their coreligionists. This found expression in education and religious spheres and jurisdiction concerning matrimonial law, but these minorities could participate neither in the affairs of the larger Muslim community, nor in state affairs. The reaya (non-Muslim Ottoman subjects, including both Christians and Jews), were regarded as second class citizens both by the government and by the Muslim public. By law they had 12 13 to wear distinctive dress and pay poll-tax, and their evidence was invalid in the courts. They were also denied permit to build or repair places of worship, perform certain ceremonies, ride horses in the towns, or walk in certain places within them. They were often subjected to oppression, extortion, and violence by both the authorities and the Muslims. This was the reason why many Jewish and Christian immigrants who settled in Palestine chose to keep their original nationality, thus gaining more privileges and security of body and property under the capitulation agreements. During the Tanzimat (Ottoman reform) era (1839-1861) the regime aimed at creating a new pattern of intergroup accommodation and fraternity among all its subjects. Ma’oz however claims that in Syria and Palestine it served in affect to aggravate and further polarize the intercommunal relationship, particularly between Muslims and Christians as well as between Christians and Jews. After the reforms of 1839, the chief rabbis were nominated in the Empires districts, including Jerusalem as Hakham Bashis (Chief Sage). After 1864, the district Hacham Bashis were chosen by a council of leaders and rabbis and the appointment was authorizes by the local Pasha, the head of the local Council and the Hakham Bashi in Constantinople. In Jerusalem he also had the title of Rishon LeZion (Foremost of Zion). The post was always held by a rabbi from the Sephardi community. Only three Chief Sephardi rabbis (the Rishonim LeZion - Foremost of Zion), were nominated by the “Sublime Porte” (the Ottoman Empire or State) for that post in Jerusalem. Rabbi Avraham Gagin (1842-1848), Rabbi Raphael Meir Panigel (1881-1893) and Rabbi Yaakov Shaul Eliashar (18931906). Together with the elite of the Sephardi community, they played an important role in leading the Yishuv. The hegemony of the Rishon LeZion was shaken with the growth of the Ashkenazi community. The major organizational forces of the “Old Yishuv” (the traditional, religious Jewish community in Palestine whose old timer members were imbued with a deep religious faith that theirs was the only way of life that should be followed in the Holy Land), were the Ashkenazi rabbinate, the heads of the Sephardi community and the Kolelim (a Kolel is a community or congregation of Orthodox Jews in Palestine, comprising individuals and families from a particular town or region in 13 14 the Diaspora who receive financial support from a halukkah - halukkah - distribution of funds collected in the Diaspora for support of needy Jews in Palestine). The Kolelim began to diversify from the 1830s onward. The main reason behind this process was the allocation of charity funds. In 1837 Jews of German and Dutch origin left the Perushim Kolel and established their own organizational and financial institution, Kolel Hod (abbreviation for Holland and Deutschland). Separate Kolelim of Hasidim and Perushim originated from districts of Poland, Hungary, Russia etc. were establishes in the 1850s and 60s. By the 1860s there were nineteen Kolelim in Jerusalem. In 1900 their number reached 30. Similarly Oriental Jewish communities broke away from Sephardi control establishing their own communal organizations, the first were the Moghrabim (North African Jews) in 1860. The Yemenites separated in 1908 and formed their own Bet Din, cemetery and Shchitah. The Ashkenazi community in an effort to minimize differences and draw the Kolelim together founded the “Va’ad HaKelali (General Committee) of the Ashkenazi Kolelim” in 1866. It elected a local rabbi as its chief rabbi of Jerusalem’s Ashkenazi population. Although not recognized by the Ottoman authorities, he wielded control over Ashkenazi community affairs. The “Old Yishuv” suffered from internal conflicts and a lack of unity and harmony, particularly in Jerusalem, its central community. A further blow to the Hakham Bashi’s control was the growth of the Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion) and Zionist movements from the 1880s onward. These adherents to the ideology of renewed Jewish settlement in Palestine, labeled the “New Yishuv” as opposed to the conservative “Old Yishuv”, that predated their migration, began to develop their own communal institutions. Some of the new nationalists and the maskilim (enlightened) had a secularist world-view. This found expression in the establishment of the Halutzei Yesud haMa`ala Committee in Jaffa in 1882. The choice of Jaffa for this institution and others was due to geographical and demographic considerations. Jaffa was the main port and was near the first Jewish agricultural settlements and the Jewish population was of a different temperament. Furthermore, Jaffa was away from the quarrels and in-fighting of Jerusalem’s Jewish population. Representatives of the Hovevei Zion movement 14 15 centered their activities in Jaffa. With the growth of Herzlian Zionism after 1897, its institutions were established in Palestine. In 1908 the Palestine Office was set up in Jaffa in order to assist in the settlement and absorption of immigrants. Jaffa rose to be not only an organizational center, but a center of ‘Hebrew culture’ including education, a library, theater, and the publication of books and newspapers. As the years passed, the process of secularization and enlightenment intensified particularly during the Second Aliyah with the immigration of young settlers who were imbued with the secular socialist-Zionist ideology. Women in this group took part in public and communal life. The ideological tensions and conflicts between the Old and New Yishuv grew. In addition, there was a struggle for control of the sources of funds from abroad, and for leadership positions within the Yishuv. In the thirty years prior to World War I the strength and status of the “Old Yishuv” and the Kolelim was eroded. The center of gravity of activity within the Jewish community in Palestine passed over to the economic institutions and cultural organizations of the “New Yishuv”. The British Mandate inherited the Ottoman millet system. It further strengthened their authority and extended it to include the Muslims as well. Of the three religions, the Jews made the best of Mandatory communal legislation to build up their national institutions that led to the establishment of the state of Israel. The events of World War I changed the balance of power among Jewish organizations in Palestine. The World Zionist Organization took on greater administrative and leadership responsibilities for the Jewish population in Palestine. The Zionist Commission (19181921), the Palestine Zionist Executive (1921-1929), and the Jewish Agency for Palestine (19291948) administered outside funding to the Yishuv and guided various policies for absorption of immigrants, settlement projects, and negotiations with the British authorities. In 1920 elections were held for the Asefat Hanivharim (Elected Assembly). Women had the vote despite objections from orthodox elements. This democratic body was established to run the affairs of the Jewish community in Palestine. It brought together the Old and New Yishuv, orthodox and secular, Ashkenazi and Sephardi. The Va’ad Leumi (National Council) was the assembly’s executive organ. The Arab Palestinian population during the Mandate period went through a short and partial process of a 15 16 crystallization as a political-national community. However, unlike the Jews it lacked an effective and broadly recognized national center and institutions. It’s contents of political identity were mostly Muslim-Arab, and expressed negative stands toward Zionism and the Jewish Yishuv. Jewish communal organization also dealt with the issue of security. Organized Jewish selfdefense began with the establishment of Hashomer (The Watchman) in 1909. It sought to protect life and property in Jewish settlements. In 1920 it was incorporated into the Haganah (Defense), the underground militia of the Yishuv. Originally responsible for defense matters, its role changed over the years, maturing to a military body. In 1947 there were 45,000 men and women in its ranks. Jewish Cultural Diversity In the nineteenth century Jews in Palestine communicated in the languages of their countries of origin, local languages (Arabic and Turkish) and also European languages. Sephardi Jews used Ladino, Askenazi Jews used Yiddish and Yemenite Jews used Arabic and Hebrew. Hebrew originally was used as a means of communication between leaders of the different communities and to some extent in daily life. With the introduction of foreign sponsored schools additional languages were introduced to Jewish youth -- French by the Alliance Israelite Universelle and German by the Hilfsverein der deutschen Juden (Ezrah in Hebrew). However, a movement arose in the 1880s, led by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda which fostered the revival of Hebrew as the lingua franca of the Jews. Despite opposition of those who saw this effort as the profanation of the sacred tongue, Hebrew became the dominant language of the Jewish community of Palestine. An important event which contributed to that effect was the language controversy - the Yishuv’s successful campaign at the end of 1913, against the decision of Ezrah to teach in German at the Technion. In 1921 the British Mandate recognized Hebrew as one of the three official languages. Arabic and English were the other two. It is of interest to note that 60 languages were recorded in the census of 1931, as being “habitual language in use”. Hebrew became the language of instruction in almost all Jewish schools as well as the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Only a small group from extreme orthodox Jewish circles continued to oppose the use of Hebrew for secular purposes. 16 17 Jewish education in the nineteenth century consisted of religious schools for boys only heders, kuttabs (religious elementary schools of Oriental Jews), and Talmud Torahs as in traditional Jewish society as well as yeshivas for higher education. In 1870, the Alliance Israelite Universelle established the Mikveh Israel agricultural school on the outskirts of Jaffa. This represented an attempt to transform local society by providing youth with new skills. Other Jewish philanthropists and philanthropic organizations established schools in Palestine (Eliza von Laemel, Montefiore and Rothschild). Some of those were for girls. The Sephardi and Oriental commmunities were more open to new modes of education, sending their sons and daughters to the new schools. In Jerusalem Dr. Nissim Bechar and Albert Antebi, introduced many changes into the “Alliance” vocational school in Jerusalem. Antebi convinced the “Alliance” to build two new schools for boys and girls, were in the mid-Mandate period studied 1,500 and 1,000 pupils respectively. Yossi please check and edit or add a connecting sentence if neede, about Bechar and Antebi. Hebrew schools became more common towards the end of the century. The school system that developed in the 28 colonies of the ‘First Aliyah’ (1882-1903) reflected parallel trends: the first was traditional religious heder or Talmud Torah education , often in Yiddish; and in the second and third ones a more secular and modern education with either stress on the French language and culture or national education with Hebrew as the main language of instruction. A purely secular nationalistic educational institution began to take shape in Jaffa in 1890. The school for both boys and girls Ashkenazim and Sephardim was supported by the members of B’nei B’rith and B’nei Moshe in Jaffa, Hovevei Zion and the Alliance Israelite Universelle. In 1906, the first Hebrew high school, Gymnasium Herzlia was established in Jaffa. The national struggle of the Yishuv for its culture and language during the “language war” in 1913, brought about the establishment of a new and prosperous Hebrew educational network. These developments influenced Hebrew education in EretzIsrael and the educational systems of the State of Israel. Following World War I the Zionist Commission established a Department of Education, a unified Hebrew system of education through which all Jewish children would receive an elementary 17 18 education in Hebrew. This measure of autonomy, or according to Rachel Elboim-Dror “this paradox of cultural colonialism” was stipulated under Article 14 of the Mandate which assured communities the right to maintain their own school system in their own language while conforming to certain general requirements. Less than 20 percent of the budget came from the British Mandatory government. Eventually administration of this educational system was transferred from the Jewish Agency to the Va’ad Leumi. This Hebrew Public System embraced at the beginning of 1939, 396 schools with 52,816 pupils. The Hebrew education was imbued with a sense of cultural superiority and national mission. Three Jewish systems were developed -- one religious under the auspices of the Mizrachi organization, the second general under the General Zionists system and the third under the Labor Zionists. Outside the system were the Agudat Israel and the Alliance Israelite Universelle schools. In addition to the educational systems described above were a number of higher education programs. In 1906 Boris Schatz established the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts to foster arts and handicrafts among the Jews of Palestine as well as developing a new national Jewish style of art. A Bezalel colony of Yemenite artisans was established at Ben Shemen. A technical school was initiated in Haifa in 1912. Only in 1924 was the Technion officially opened. The following year the Hebrew University of Jerusalem was formally opened. Teaching at first was limited to a number of fields Jewish studies, oriental studies, humanities, and mathematics. Research focused on the sciences -physics, chemistry, microbiology, hygiene and the botany and zoology of Palestine. In 1940/41 it had an enrollment of 1,118 (809 men and 309 women).The Hebrew Teachers Seminary was established in Jerusalem to train educators. Towards the end of the Mandate period an Information Paper of the Royal Institute of International Affairs claimed that one of the unique characteristics among immigrants found among Palestine’s Jews is “the predominance of a far higher standard of education and technical skill than is common among settlers”. The percentage of immigrants who had received a secondary education, the paper adds was striking. 18 19 In 1863 two pioneering Hebrew newspapers began their publication in Halevanon and Habazeleth. The publishers were Ashkenazi. To the second Jerusalem - one was added for a short while a supplement in Ladino, for the Sephardi readers. A shortlived bi-monthly Hebrew and Yiddish (!) newspaper, Shaarei Zion (1876 - 1884) was considered, a Sephardi mouthpiece. The others hardly reported on the Sepahrdi Kolel, its welfare houses, or the part of the Sepharadim in the new neighborhoods. Moshe A. Azriel and Shlomo Israel Shirizli opened two printing houses in Jerusalem to supply the demand for Ladino publications in Palestine and abroad. In 1909, to counter-balance the political views of Ben-Yehuda’s newspapers Hatzvi and Ha’or, several Sephardi activists including Antebi, Azriel, Haim Ben-Atar and Avraham Elmalech established Haherut, a Jewish nationalist newspaper for Sepharadim. From a Ladino weekly it soon switched into Hebrew with a daily circulation of 2,000 in the Yishuv and other Mediterranean Jewish communities. Its editorials supported Jewish colonization in Palestine, Hebrew and National education, and Arab-Jewish rapprochement. Dr. Shimon Moyal conceived the idea of an Arabic-Hebrew newspaper, Saut al-’Uthmaniyya (The Ottoman Voice), which, in fact, appeared in Jaffa from 1913-1914. In 1932 Elmalech and the lawyer Meir Laniado tried to renew the publication of Haherut but it was short lived. Elmalech, a proliferous scholar and writer, initiated in 1919 the publication of Mizrach Oumaarav (Orient et Occident). He viewed it as a non-political scientific, historic, and literary journal aimed at presenting the great heritage, history, customs, and rabbinical and literary writing of the Sephardi and Oriental communities, which were hardly studied. . Closing after a year, it reopened in 1928 for four years as a monthly supported by the World Federation of Sephardi Jews, and several Oriental committees. In 1942 a new mouthpiece of the Sephardi Jews - Hamizrach (The Orient) later renamed Heid (Ecco) Hamizrach, was started in Jerusalem. Its first editor was Eliyahu Elyashar. This organ aspired to express the life, opinions, wishes, and demands of the Sephardi and Oriental communities in Palestine which constitutes a third of the Yishuv. It ceased appearing in 1951. One characteristic of the Sephardi and Oriental social groups was a similar lifestyle in each, expressed through housing, food, dress, customs, festivals, rituals etc. These distinguished between one community and another, and made them unique. Among the Sephardi and Oriental communities was the importance of extended family, characterized by a feeling of unity, religious tradition, honoring of parents and elderly, and the wish to marry the children at an early age (12-14). Among the Yemenites marrying several wives was still common. Intermarriage between communities was not 19 20 frequent. The women ran the household. Family life concentrated in the enclosed courtyards. Cooking, washing, cleaning and sometimes eating took place there. Shared by several families it was also a focus of social life, and enabled mutual aid. Sephardi and Oriental women stayed mostly at home. Men went to work and to the market. The meals were simple. Meat and fish were served only on the Sabbath. Among the Sepharadim, the Purim (Feast of Esther) holiday was an important one. Other celebrations were on Lag BaOmer at Meiron, and the one near the Tomb of Shimon Hatzadik in Jerusalem. In Jaffa, the lifestyle of Sephardi, Maghrabi, and other Oriental communities was much influenced by the new trends. The young generation of Yemenites in Tel Aviv in 1930 spoke Hebrew and: “... aspire to become “Europeans” ...visit the theaters, still movies, concerts etc.” The Zionist culture came as an addition to the culture of Enlightenment, which preceded it. The Sephardi elite, embraced the Enlightenment (Haskala) and added to it values of national revival in its older version of proto-Zionism. Sephardi rabbis supported Zionism as long as it did not break with its beliefs and traditions, which guided community patterns and daily life. They opposed its secular revolutionary dimension. Yossi, please edit if necessary, and check if it fits here. If so add also to list of sources. The interaction between the Edot brought about thoughts on what was common -- Hebrew, the study of Torah, the practice of מצוותand holiday celebrations. On the other hand we find friction, as evidenced by redicule and hostile attributions. Some written sources describe interethnic stereotypic perceptions as follows: the Ashkenazis claimed that the Sephardis were lazy both in mind and in actions, and the glory and adornment of their leaders concealed their dullness. The Sephardis responded that the Ashkenazis were crafty, sycophants, cheats, and “shnorers”. The Yemenites gained a good name among the other Edot. They were considered clever, industrious, quite, pleasant and somewhat docile and obedient. The Maghrabis were very poor, as their rich class did not come. The Bucharans did not exel in scholarship, but quite a few of them were rich, and supported Sephardi institutions because of the honour given to them. The Georgians were known as healthy in body, and work lovers. The Kurds were known (not un-biased) to have physical streangth, and ones who treatsome negativ traits as lack of culture, primitiveness, and as treating their women as oriental despots. These were compensated by their industriousness which 20 21 contributed to the building of the country. Others attributed to the Kurds a rich folklore of stories and legends. (Mea Shana, I, p.56; Yisrael Yeshayahu, “Changes Among Yemenites”, Bamaaracha, No. 10, Tel Aviv, 6 April 1948, p. 5; Meir Frenkel, “The Kurdistani Jews”, Hagalgal, Vol. 5, No. 37, 8 April 1948, pp. 6, 18; Yona Chohen, “Edot Hamizrach in Jerusalem”, Hagalgal, Vol. 5, No. 6, 11 September 1947, pp. 8-9). From Economic Dependency to Entrepreneurship and Utopian Experimentation In the early nineteenth century the Jews in Palestine earned their livelihood mainly from trade and handicrafts (metal and textile). Funds sent by Jews in the Diaspora by five bodies: Hasidim, Perushim, “Va’ad Pekiday Eretz-Israel be-Kushta” “Irgun Hapekidim vehaamarkalim meAmsterdam” and emissaries sent from the four “Holy Cities” provided the main income for the Jewish population. The method of allocating these halukkah funds varied among the Jewish communities. The Sephardi community used the moneys for community needs (taxes, institutions, salaries etc.), support of scholars and the needy - widows, orphans, and the aged. The Ashkenazi groups provided subsidies for all their members. This afforded them with the possibility of devoting themselves to the study of Torah and not working. The amount received varied according to the size of the contributions from abroad and the number of members in Palestine. As such in 1839 one finds that in Jerusalem out of a total of 1,751 breadwinners, 229 Sepharadim and 28 Ashkenazim earned their livelihood from physical labor and crafts. The remainder were supported by halukkah funds. Some members of the “Old Yishuv” were influenced in the 1850s to the 80s by messianic preachers of the redemption and settling of the land of Israel such as Rabbis Zvi Hirsch Kalischer and Judah Ben Solomon Hai Alkalai, and the founding in 1860 of the Society of “Yishuv Eretz-Israel” by Hayyim Luria in Frankfurt. These ideas, combined with the wish to replace halukkah with heightened productivity and an enhancement of the economic situation of the “Old Yishuv”, led some to buy and develop rural land privately, and others to established societies for the purchase, settlement and cultivation of land. 21 22 The mid-nineteenth century saw certain changes in the Jewish economic structure. New immigrants as well as local entrepreneurs, mainly Sephardi and North African families (Amzalak, ‘Abu, Moyal, Chlouche, Valero) established themselves mainly in the coastal towns - Jaffa and Haifa. In addition to crafts, they engaged in modern commerce, real-estate, transportation and banking and later in small-scale industry. This activity was facilitated by their contact and representation sometimes as consular agents of the European nations. In the middle third of the nineteenth century, and before the formation of the “New Yishuv” this group together with Christian settlers and the Arab elite was already involved in the process of productivization and modernization. All of them were the main pioneers in introducing modern technologies into Palestine. During the last two decades of Ottoman rule, Jewish economic activity started to flourish. Improved transportation with Europe and the infusion of capital underlined this process. The Jews became an important element, together with other sectors of the population, in the development of Palestine’s commerce, agriculture and fledging industry. Despite the set backs caused by World War I, after it Jewish economic activity further expanded into industry. During the period of British rule it was facilitated by an improved infrastructure of electric power stations and transmission lines, roads, railroads and the new harbor facilities at Haifa. Jewish industrial enterprises grew in number from 536 with a personnel of 4,894 in 1925 to 2,120 establishments with 45,049 employees in 1945. It was under the British Mandate in the period 1921-1936, that the traditional Arab sector as well experienced fast and wide-ranging technological progress. An important force in the economy of Jewish Palestine was the Histadrut (the General Federation of Jewish Labor). Established in 1920 it functioned as a trade union and simultaneously developed economic enterprises including cooperative credit institutions, consumer cooperatives, producers’ cooperatives, housing cooperatives, agricultural cooperatives, manufacturing associations, insurance and construction companies. Furthermore it was involved in various social and cultural activities. It organized a sick fund Kupat Holim, unemployment funds, disability funds, and old age pension funds. Membership rose from 53% of the Jewish workers in 1925 to 74% in 1945. 22 23 The field of agriculture underwent a radical change during the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century. In the early nineteenth century only a small number of Jews were engaged in agriculture. Sources point to farmers in the northern villages of Pekein, Kfar Yasif and Shefaram. By the 1830s there were attempts to expand Jewish agricultural activity. Sir Moses Montefiore, a proponent of Jewish productivization searched for appropriate lands for the establishment of 200 agricultural settlement. In the 1850s Jewish and Christian groups developed irrigated gardens and a Model Farm in the vicinity of Jaffa aimed at inspiring Jews to agriculture or training them in this direction. Some Jews invested in irrigated gardens focusing production of the lucrative orange market. With the promulgation of the new Ottoman land law in 1858 and its ratification with foreign governments land purchase was facilitated. Various plans were proposed to establish Jewish agricultural settlements. In 1878 two failed attempts at Jewish agriculture were made in the Sharon (Petah Tikvah) and the Galilee (Gei Onni later Rosh Pinna). The First Aliyah brought new immigrants with capital and the proto-Zionist motivation for the return to the soil. In 1882 four settlements were founded Rishon Lezion, Rosh Pinna, Zichron Yaakov, and Petah Tikvah. By 1904 there were twenty-eight Jewish settlements with approximately 5,500 residents on nearly 23,500 hectares (1 hectare = 2.471 acres). The Baron Edmund de Rothschild provided supported most of these settlements. The administration of the Baron's assistance guided the direction of activity and for a time focused on monoculture and with its agricultural based industry, for example the wine cellars of Rishon Lezion and Zichron Yaakov or the silkmill at Rosh Pinna. In 1903 the Jewish National Fund, the land purchasing instrument of the World Zionist Organization was established. Certain Zionist schools of thought perceived a restructuring of the Jewish economy with a large number of settlers engaging in primary activities as in other nations. Penslar’s recent study on the engineering of Jewish settlement in Palestine, 1870-1918, presents the creation of a Jewish homeland in modern Eretz-Israel as a monumental technical achievement. It differentiated among three schools of technocrats and settlement engineers: the French, the German 23 24 and the East European, which attempted to transplant European social and agrarian policies on Middle Eastern soil. On lands belonging to the Jewish National Fund kibbutzim (sing. kibbutz: communal settlement) and later moshavim (sing. moshav: cooperative settlement) were founded. On the eve of World War I, the Jewish National Fund had acquired 1,380 hectares of land. Its holdings increased to 86,500 hectares in 1946. In 1946 the area of land in Jewish possession amounted to 180,700 hectares, i.e. 6.8% of the total area of Western Palestine. The spatial distribution of the Jewish population and settlements in Palestine on the eve of independence, was determined by the availability of land bought and owned by Jews. It resembled the shape of the letter N on the map of the country, going along the coastal plain on the west, through the Kishon, Jezreel and Beit Shean Valleys and then north along the Jordan Valley (See Map 2). Private capital also served to expand Jewish agricultural activity. Citrus groves, the most lucrative form of agricultural investment, were planted along the coastal plain. In 1945 72,486 hectares of Jewish owned land were cultivated including 12,000 hectares of citrus plantations. The progress made in agricultural settlement was striking. From a few villages with a population of 500 in 1885, it reached within 60 years a population of 153,000 living in 266 villages. While in 1890, 8 years after the beginning of modern Jewish settlement on the land, only 6 Jew out of every hundred lived in villages, in 1945 the ratio was 25 to hundred. A unique contribution of the Jewish sector in the urban sphere was the introduction and application of novice European town planning and architectural ideas such as the Garden City, Garden Suburbs , Workers’ Estates and Working Class Housing, and the International Style and influences of the Bauhaus school in architecture. The results of the expansion of agriculture and the development of industry were a significant change in the employment structure of Jews in Palestine as compared to Jewish communities abroad (See Table 4). A characteristic of the Jewish population in Palestine unusual among immigrants was the remarkably high percentage of newcomers of independent means who entered Palestine in the interwar period. It was partially due to Mandate authorities certificate policy limiting the settlement of immigrants without means. This capital and investment by Jews in the Diaspora spurred economic 24 25 growth, but when misdirected to real estate speculation brought about economic hardship. In 1926 crisis set in and resulted in high unemployment and a negative net Jewish migration the following year. The 1930s were again years of growth which was partially due to the captial transferred by German Jewish immigrants. During World War II the economy further expanded since it was geared toward supporting the allied war effort. Some 25,000 Jews (including almost 4,000 women) enlisted in the British Army. The economic foundations were laid for absorbing the “she’erit hapleita” (displaced persons) and an independent state. At the end of the Mandate period, the Jew of Palestine, in spite of their growth and strengthening, were still a minority in a country ruled by a foreign power, as well as in the Jewish world. The Arabs of Palestine, which comprised two thirds of the population, viewed them as a foreign colonial element intending to displace them. The solution suggested by the United Nations was a territorial partition of Palestine and the creation of two States, Arab and Jewish, did not materialize, and the State of Israel was established as an outcome of an armed conflict and war. Conclusion In the one and a half centuries between Napoleon’s invasion to the Near East and the founding of the State of Israel (1799-1948) the Jews of Palestine passed through several major stages of transformation. Political and economic changes in the international and regional arenas, and legal, economic, social, cultural and ideological processes and trends in Europe and North America and in the Jewish world, brought about these transformations. It’s population grew from about 5,500 souls (2.2% of the total population) in 1800, to 650,000 (32%) in 1948. On the eve of Israel’s independence the Yishuv’s percentage among world Jewry was 5.5%. Some of the determinants of change and modernization were unique to the Jewish community in Eretz-Israel, while others characterized the whole Near East and North Africa, and other Jewish and non-Jewish communities and sects. A uniqueness of the Yishuv compared to Jewish communities in the Diaspora was its growing internal variety of Jewish ethnic groups and communities, and Eretz-Israel being the site of messianic yearning and Zionist national aspirations. 25 26 The main dominant types of the Yishuv during the rule of two major external powers - the Ottoman Empire, and Britain, were, in a simplified chronological presentation as follows: Old Yishuv I - mainly Sephardi traditional, religious, small, and partially unproductive community depending on charity, living only in the four ‘Holy Cities’ (Tiberias, Safed, Jerusalem, and Hebron). The traditional attachment of the Jews to Eretz-Israel led to the Aliyah of Hassidim and Perushim from Eastern Europe. The Yishuv was peripheral both in the Jewish world and in Palestine and the Ottoman Empire in the first third of the nineteenth century. Old Yishuv II - in the middle third of the nineteenth century, still a traditional, religious community but with an improved legal and social status due to the opening of foreign consulates and the Ottoman reforms. Growing immigration from North Africa and Europe, led to the founding of additional Jewish communities and institutions in Palestine, some of them more productive and entrepreneurial in the urban and rural spheres. Growing ratio and variety of the Ashkenazis in the Yishuv, and a shift of its center of gravity from the Galilee to Jerusalem. The spirit of Western Jewish Enlightenment and modernization reaches the Jewish population. First Jewish attempts at agriculture are made, new residential quarters built, modern schools opened and the first newspapers published. New Yishuv I - 1882-1918, included a less conservative and more educated, secular and productive sector of the local Jewish community and immigrants of the First and Second Aliyot of Hovevei Zion and Zionists who came to settle in Palestine. Members of the New Yishuv were involved in modern economic processes. A changeover to a new society and way of life, and different ideological concepts of the goals of their settlement in Palestine included national aspirations, personal fulfillment, agricultural settlement, manual labor, nationalization of land, co-operation and equality. An attempt to fulfill an utopian vision and transplant contemporary European social policies, and agrarian and urban planning concepts in the country. The establishment of new institutions and secular Hebrew schools. The center of gravity of the New Yishuv moves to Jaffa. There was a rise of conflicts between old and new populations as the traditional section of the “Old Yishuv” tried to 26 27 protect itself from modernization processes, and establish an utopian society that will preserve it’s traditional worldview and frameworks. In the “New Yishuv an alliance between the World Zionist Organization and Labor Zionism began. Negative attitudes of the Ottoman Government and the Arab local population towards mass Jewish immigration, land purchase and settlement with national aspirations in the country, increased. New Yishuv II - 1918-1948, The promise of creating a homeland for the Jews in Palestine underlined many of the Jewish community’s activities and developments. The Jews became a legitimized and much more autonomous and central sector of the country’s population, running its own institutions. The World Zionist Organization and its local institutions took a central role in many spheres. The foundations were laid for the building of an independent Jewish economy, and the central institutions of the Labor Movement (the Laborer’s parties, the Histadrut, the Kibbutz, Hashomer and the Haggana). Tel Aviv, the first Jewish-Hebrew city and Haifa and its bay became main population, administrative, economic and cultural centers of the modern sectors of the New Yishuv and the influx of immigrants of the new legal and illegal Aliyot. After World War I when the modern Jewish settlement enterprise was resumed, Zionist thinkers, settlement activists and leaders of Zionist institutions grew more convinced that the redemption of the land of Eretz-Israel by Jew bore social and educational message besides being a pioneering act and a means for obtaining territory for the Jewish people. The conviction that physical presence on the land was no less important than the legal right of possession strengthened after the events in Germany and German immigration to Palestine from 1933 onwards. A change in policy and an adoption of a Geopolitical strategy in the settlement sphere occurred after the Arab Revolt in 1936 and the change in British policy that followed it. The conflict between Arabs and Jews strengthened mainly due to competing on the main two resources essential to the success of the Zionist enterprise - land and labor. The Jewish attempt to “conquer” labor failed, while the attempt to establish collective agricultural settlement on national land with The Zionist Organization’s assistant was highly successful. The New Yishuv II and its institutions laid the foundations for the first conceptual and governmental frameworks of the independent State of Israel. 27 28 Suggestions for Further Reading Yossi add from Columbia paper - Almaleh, Ben Zvi, Druyan, Gaon, Gurevich-Gertz A Survey of Palestine prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the Information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry. 3 vols. Jerusalem: Government Printer, 1946. Yossi, add Barnai’s book in Hebrew (the English title). Bachi, Roberto. The Population of Israel. Jerusalem: xxxxx, 1977. Ben-Arieh, Yehoshua. Jerusalem in the Nineteenth Century,2 Vols. Jerusalem and New York: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi and St. Martin’s Press, 1984 and 1986. Glass, Joseph B. and Ruth Kark. Sephardi Entrepreneurs in Eretz Israel, the Amzalak Family 18161918. Jerusalem: Magnes Press ,1991. Kark, Ruth (ed.). The Land That Became Israel, Studies in Historical Geography. New Haven, London, and Jerusalem: Yale University Press and Magnes Press, 1990. -- Jaffa, A City in Evolution, 1799-1917. Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi, 1990. Kark, Ruth and Oren-Nordheim Michal. Jerusalem and its Environs, 1800-1948. Jerusalem: Magnes Press (in press). Kimmerling, Baruch. Zionism and Territory, The Socio-Territorial Dimensions of Zionist Politics. Berkeley: University of California Institute of International Studies, 1983. -- Zionism and the Economy. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman Publishing Company, 1983. Kushner, David (ed.). Palestine in the late Ottoman Perid, Political, Social and Economic Transformation. Jerusalem and Leiden: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi and E.J. Brill, 1986 Laskier, Michael M. “The Sepharadim and the Yishuv in Palestine: The Role of Avraham Albert Antebi: 1897-1916,” Shofar 10:3 (Spring 1992), 113-26. Add McCarthy’s book? (Pop. of Pal.) Ma`oz, Moshe (ed.). Studies on Palestine during the Ottoman Period. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1975. Parfitt, Tudor. Tha Jews in Palestine, 1800-1882. Exeter: The Royal Historical Society, 1987. 28 29 Penslar, Derek, J. Zionism and Technocracy, The Engineering of Jewish Settlement in Palestine, 1870-1918. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1991. Royal Institute of International Affairs. Great Britain and Palestine, 1915-1945. Information Paper No. 20, London and New York, 3rd edition, 1946. Yossi - Add Scmelz? Schmelz, Uziel O. “The Decline in the Population of Palestine during World War I”, in: Eliav Mordechai (ed.). Siege and Distress, Eretz Israel during the First World War. Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi, 1991, 17-47. Yossi - Add Scolch? 29 30 Yossi, New updated list of Tables, Figures and Plates Maps and Tables Map 1: The process of spatial change in Palestine, 1800-1914. Source: Ruth Kark, “Landownership and Spatial Change in Nineteenth Century Palestine: An Overview,” In: Roscizewsky, M. (ed.). Transition from Spontaneous to Regulated Spatial Organization, Warsaw: Polish Academy of Sciences, 1984, p. 86. Map 2: Jewish land ownership and settlement, 1947. Source: Palestine: Land in Jewish Possession (as of 30.6.47). Survey of Palestine. 1:250,000, April 1947. Table 1: Population of Palestine according to religious groups during the British Mandate (in thousands) Year 1922 percent 1931 percent 1946 percent Muslims 600.7 78.7 759.7 73.5 1,141.5 60.2 Jews 83.8 11.0 174.6 16.9 593.8 31.3 Christians 71.5 9.4 88.9 8.6 144.5 7.6 Others 7.6 1.0 10.1 1.0 15.2 0.8 Total 763.6 100.0 1,033.3 100.0 1,895.0 100.0 Source: R. Bachi, The Population of Israel. Table 2: Jewish Rural and Urban Population (selected cities) in Palestine (1800-1945) Year Jerusalem Jaffa Tel Aviv Haifa Safed Tiberias Hebron Rural settlements Total population 1 1800 2,000 0 + 0 2,250 1,000 300 * 5-6,000 1840 (1835)1 5,000 200 + * 1,500 (3,750) 1,000 (1,700) 400 * 8,700 1880 (1890) 18,000 1,000 + 600 4,300 2,400 900 * (3,000) 27,000 1914 1922 45,000 33,970 10,500 4,960 1,500 15,190 3,000 6,230 7,000 2,990 6,000 4,430 1,000 430 12,000 15,712 85,000 83,800 1931 53,800 7,700 46,300 16,000 2,500 5,400 0 38,450 174,600 1945 97,000 34,000 174,000 66,000 2,400 7,000 0 152,800 592,000 Estimate before the 1837 earthquake * Negligible amount + Tel Aviv was founded in 1909 Source: D. Gurevich, Statistical Handbook of Jewish Palestine, 1947 (Jerusalem: Jewish Agency for Palestine, 1947), 48; Y. Ben-Arieh, “The Development of twelve Major Settlement in Nineteenth Century Palestine,” Cathedra 19 (April 1981), 83-144. 30 31 Table 3: Jewish Population by Communities Palestine 1918 Palestine 1936 Palestine 1945 Jerusalem 1939 Rural population 1941/42 Ashkenazim Sepharadim Yemenites 33,000 (58.9) 310,000 (76.7) 460,000 (77.7) 38,256 (50.9) 116,271 (86.6) 4,400 (7.9) 18,000 (4.4) 29,000 (4.9) 3,632 (4.8) 7,628 (5.7) 11,000 (19.6) 37,000 (9.2) 57,000 (9.6) 10,067 (13.4) 6,275 (4.7) Other oriental communities 7,600 (13.6) 39,000 (9.7) 46,000 (7.8) 23,195 (30.9) 4,102 (3.0) Total 56,000 (100.0) 404,000 (100.0) 592,000 (100.0) 75,150 (100.0) 134,276 (100.0) Source: Gurevich, ibid, 60.. Table 4: Occupational structure of Jews: Palestine 1939, North Africa 1936, and Global estimate 1940. Sector Palestine Agriculture 19.3 Industry, handicrafts, building and 27.1 construction Commerce and insurance 14.1 Transportation 5.7 Public service and liberal 14.6 professions Others 19.2 Source: Gurevich, ibid, 72. 31 North Africa 1.5 36.2 Global 3.0 35.8 40.0 2.3 9.1 38.8 including transportation 10.9 14.6 7.8