paid-content-debate-msword

advertisement

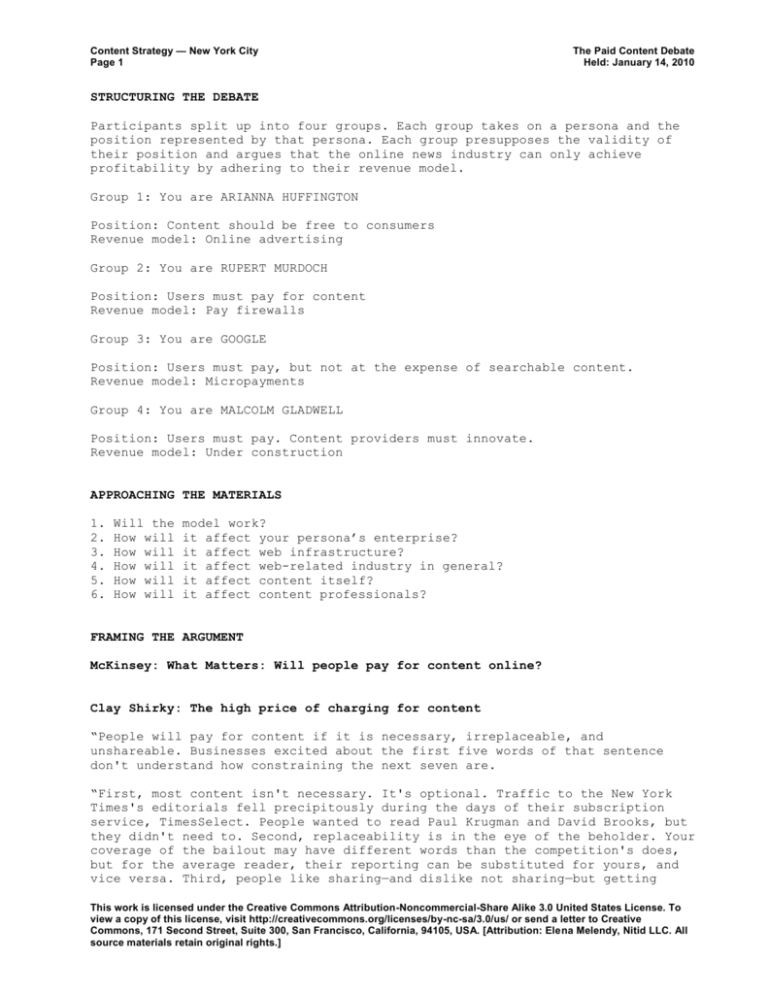

Content Strategy — New York City Page 1 The Paid Content Debate Held: January 14, 2010 STRUCTURING THE DEBATE Participants split up into four groups. Each group takes on a persona and the position represented by that persona. Each group presupposes the validity of their position and argues that the online news industry can only achieve profitability by adhering to their revenue model. Group 1: You are ARIANNA HUFFINGTON Position: Content should be free to consumers Revenue model: Online advertising Group 2: You are RUPERT MURDOCH Position: Users must pay for content Revenue model: Pay firewalls Group 3: You are GOOGLE Position: Users must pay, but not at the expense of searchable content. Revenue model: Micropayments Group 4: You are MALCOLM GLADWELL Position: Users must pay. Content providers must innovate. Revenue model: Under construction APPROACHING THE MATERIALS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Will the How will How will How will How will How will model work? it affect your persona’s enterprise? it affect web infrastructure? it affect web-related industry in general? it affect content itself? it affect content professionals? FRAMING THE ARGUMENT McKinsey: What Matters: Will people pay for content online? Clay Shirky: The high price of charging for content “People will pay for content if it is necessary, irreplaceable, and unshareable. Businesses excited about the first five words of that sentence don't understand how constraining the next seven are. “First, most content isn't necessary. It's optional. Traffic to the New York Times's editorials fell precipitously during the days of their subscription service, TimesSelect. People wanted to read Paul Krugman and David Brooks, but they didn't need to. Second, replaceability is in the eye of the beholder. Your coverage of the bailout may have different words than the competition's does, but for the average reader, their reporting can be substituted for yours, and vice versa. Third, people like sharing—and dislike not sharing—but getting This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Page 2 The Paid Content Debate Held: January 14, 2010 people to pay for content requires forbidding us from forwarding things we care about to family and friends. “In an analog world, per-copy pricing is a strategy for increasing the number of available copies. In a digital world, per-copy pricing is a strategy for decreasing the number of available copies. Pay wall revenues thus reduce audiences and ad revenues, while creating a competitive advantage for (and an audience exodus to) subsidized outlets—whether the subsidy comes from advertisers or users. “Pay walls also threaten syndication revenues, because syndicated content from even one subsidized outlet will spread at the expense of all locked-down versions. “Fees thus attach to special cases: people pay Cook's Illustrated to reward it for not taking ads. People pay the Financial Times because financial data is valuable in inverse proportion to its availability (unlike editorials, say, or political reporting). Harnessing users to expand reach is simple, cheap, and powerful; even if you commit yourself to pretending content is scarce, many of your competitors won't. This dynamic creates a competition between organizations working with and against the Internet's innate capabilities. “The key questions for the average publisher contemplating pay walls are: How serious will that competition be? How many users will you lose? Will banning sharing create a defensible advantage? And the answers are: crushing, most, and no.” Steven Brill: Two revenue streams are better than one “When we launched Journalism Online last April there was a great deal of misunderstanding about what we were doing. We were not suggesting that any publication go behind a pay wall. Rather, we're enabling publishers to sell content (mostly through subscriptions, although there may be some micro-sales) to a small portion of their online audience while maintaining the traffic necessary to sustain advertising revenue. “So, if there's to be a debate about whether our model makes sense, it ought to center on this question: Will, or should, publishers who invest in significant original content—be they newspapers, magazines, or online only sites—continue forever to give away everything they produce to everyone who wants it? Or, as advertising rates continue to plummet amid a growing glut of inventory, should they, and can they, create a circulation revenue stream, too? Here are three of the ways our 16-dial Reader Revenue Platform™ enables them to do that: “Sampling: Publishers will set a dial so that only the most avid online readers are asked to pay. Everyone else will continue to read, and see ads, undeterred. These avid readers may be defined as those who come to the site ten times a month, or 30, or six—or any other measure of engagement the publisher sets (and re-sets as the market develops). “Market Access Pay Points: Publishers will adjust payment requests and amounts based on whether the reader is in- or out-of market. Thus, a newspaper based in London with a small but highly engaged U.S. audience could charge them (and sacrifice minimal ad revenue because its advertisers are likely to be looking for a UK audience.) Or, a college newspaper could use Market Access Pay Points to get alumni and parents to pay a few dollars a month while keeping the paper free to the college community. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Page 3 The Paid Content Debate Held: January 14, 2010 “Select Content Pay Points: Publishers can charge for certain high value content (perhaps in concert with a sampling plan), while keeping much of the site free. “Thus, we're not suggesting that any publisher make an either-or choice between ad revenue and reader-revenue but, rather, that publishers do what they've always done: go for both.” Shirky's response to Brill “Journalism Online assumes that publishers' failure to retain pricing power online is a readily reversible accident. Were this true, any publication could start charging tomorrow, as JO's technical solutions aren't rocket science. Publishers can't start charging tomorrow, of course, because their problem isn't technology—it's new and brutal competition. JO's real offering isn't tools, but collusion. “Adding fees online inhibits use while rewarding disloyalty. Deciding to aggravate only your most faithful users, alumni, or expats limits this tradeoff but doesn't change it. It's no accident that the Big Three fee-for-content services—the FT, the Economist, and the WSJ—all reach price-insensitive audiences. The sad fact for most publishers is that there is no cartel large enough to make the average reader similarly price insensitive, and no user revenues that can offset competition from ad-supported and nonprofit publishers.” Brill's response to Shirky “This exchange demonstrates how last year the either/or debate has become. In fact, I agree completely with Clay's analysis, so this isn't much of a debate. We're against the same pay walls he is. What we're all about is providing our multidial Reader Revenue Platform™ to enable publishers to charge only their most engaged, addicted customers only for that which is, as Clay puts it so well, "necessary and irreplaceable." As for his point about readers being able to share, he's right, and we have a plan for that too. Space constraints don't allow me to describe it here in detail, but it has a lot to do with our sampling and viral marketing strategies.” —Clay Shirky is associate new media professor in the ITP grad program at NYC. Steven Brill founded Journalism Online, among other things (McKinsey & Co., What Matters, 10/14/2009). http://whatmatters.mckinseydigital.com/the_debate_zone/will-people-pay-forcontent-online This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 1: You are: ARIANNA HUFFINGTON The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 YOU ARE: ARIANNA HUFFINGTON Position: Content should be free to consumers Revenue model: Online advertising History “Information Wants To Be Free. Information also wants to be expensive. ... That tension will not go away.” —Stewart Brand, The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT, Viking Penguin, 1987 (ISBN 0-14-009701-5), p. 202. “In 1990 Richard Stallman restated the concept but without the anthropomorphization: I believe that all generally useful information should be free. By 'free' I am not referring to price, but rather to the freedom to copy the information and to adapt it to one's own uses... When information is generally useful, redistributing it makes humanity wealthier no matter who is distributing and no matter who is receiving.” —Dorothy E. Denning, Concerning Hackers Who Break into Computer Systems, in Proceedings of the 13th National Computer Security Conference, Washington, D.C., October, 1990, pp. 653–664 (online) [Via Wikipedia. Speaking of which:] "Imagine a world in which every single person on the planet has free access to the sum of all human knowledge." — Jimmy Wales, Founder of Wikipedia, in an appeal for donations. (Right now.) “Rupert Murdoch's move to charge for content opens doors for competitors” “Vivian Schiller, now CEO of National Public Radio in the US, said in an interview with Newsweek last week that talk of charging for news online is ‘mass delusion’. She should know. Schiller was head of nytimes.com when it charged and then stopped charging for its content. “If you can charge for your content - if you are the FT or the Wall Journal, the only brands that do it successfully - and your readers money on your content, and pass the cost of it onto their employers nothing against it. But for most, pinning hopes for the survival of charging for it is not only futile but possibly suicidal. Street can make I have news on “Charging for content brings marketing and customer-service costs. Online, it reduces audience and the advertising they justify. Putting content behind a wall cuts it off from search and links; they cut off your Googlejuice. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 1: You are: ARIANNA HUFFINGTON The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 “When publishers build those walls, they open the door for free competitors, who can now enter the content business with virtually no barrier to entry. Publishers who fool themselves into thinking pay will save the day only further forestall the innovation and experimentation that is the only possible path to success online. “FT editor Lionel Barber has predicted that most newspapers will charge online because they should - and should never have given away their content. But I've never heard a business plan built on the verb ‘should’. “Newspapers have had 15 years since the launch of the internet browser to reimagine and rebuild themselves for the reality of the post-Gutenberg age. But they didn't. Now they are trying to reclaim old business models for a new media economy — a link economy, I call it, in which links give content value. Cut yourself off from links, behind pay walls, and you cut yourself off from the internet and its real value.” —Jeff Jarvis, journalism professor at NYU and author of What Would Google Do? (The Guardian, 8/6/2009) http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2009/aug/06/rupert-murdoch-charging-for-content FOR DISCUSSION General: Will the model work? How will it affect your persona’s enterprise? How will it affect web infrastructure? How will it affect web-related industry in general? How will it affect content itself? How will it affect content professionals? Specific: Can online advertising still proffer a viable economic model for editorial websites? How has the economic downturn over the last few years influenced this debate? Does Jarvis’s point about paid content models cutting off search and links make sense from a content strategy perspective? Who does Arianna Huffington think she is? This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 2: You are: RUPERT MURDOCH The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 YOU ARE: RUPERT MURDOCH Position: Users must pay for content Revenue model: Pay firewalls Why Media Must Charge for Web Content “The high cost of producing original content historically was subsidized at newspapers and other media by the sale of subscriptions and advertising. “With a few exceptions like Consumer Reports, which accepts no advertising and relies entirely on subscription sales, most of the media that sell advertising charge nominal subscription rates to build the largest possible audience. “This worked quite well in the pre-Internet era, when publishers for the most part were able to charge sufficiently high ad rates to subsidize the cost of content and make a handsome profit. “When the Internet emerged, most publishers committed the Original Sin of thoughtlessly giving away their content for free in the hopes of attracting millions of page views where they could sell the sort of high-priced ads that had built the value of their print franchises. This monumental strategic blunder resulted in three major unintended, and unfortunate, consequences: By giving away their content on the web, publishers made it unnecessary for consumers to subscribe to the publications that generated the high advertising revenues that subsidize the cost of producing content. When advertisers saw audiences begin to shrink, they cut back their advertising. That’s why many newspapers have gone from typically being more profitable than Wal-Mart and even some oil companies to hanging on by a thread. Publishers devalued their once-powerful franchises by letting anyone link freely to their content on the web. In so doing, publishers inadvertently subsidized the rise of any number of aggregators that have done quite well by selling low-priced advertising next to the expensive content that the publishers kindly let them have for free. The low price of the advertising on those websites is attracting ever-greater shares of the ad dollars formerly spent at the traditional media companies. At the same time, virtually unlimited ad inventory at competing online venues has driven down the rates newspapers can charge for both print and online advertising. The wide availability of free content on the web quickly convinced consumers, who didn’t need much persuading, that content should be free. Apart from crossword fanatics like my brother in law who has to have a newspaper on which to write the answers, most consumers saw no particular reason to pay for a paper when the same information could be obtained more quickly and conveniently on the Net or an iPhone.” … “[I]t is unreasonable to believe generic news can be effectively sequestered behind a pay firewall. A publisher attempting to do this simply would divert readers from his site to some else’s, throttling the traffic that is the lifeblood of any media business. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 2: You are: RUPERT MURDOCH The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 … “Now, on to the business of trying to save the media business. “If we are going to save the tradition of professional journalism, it is vital for publishers to begin producing content that is sufficiently unique, authoritative and valuable to motivate consumers to pay for it. “The need for the traditional media companies to produce more and better content could not come at a worse time. Newsroom budgets are being gutted by historic declines in ad sales, aggravated by the need for many companies to generate unreasonably large profits to service the heavy debt they incurred to fund ill-considered and ill-timed acquisitions. “As a direct consequence of the breakdown in the traditional media business model, publishers today are cutting the quality and quantity of the content they produce at the very moment they should be investing more aggressively than ever in the sole distinguishing capability that powerfully differentiates them from the millions of websites that are siphoning away their readers and advertisers. “As the most challenged of all the distressed media companies, newspapers are so strapped today that they are producing ever less original reporting. In but one example of the decimation, the number of reporters covering the nation’s capital for American newspapers has dropped by half since 1995 to 300 correspondents. “This is not merely a step in the wrong direction. It is a leap into the abyss. “Fortunately for publishers, for-pay content doesn’t have to be the Watergate investigation of the future. People will pay for all manner of content on the web, it if it is thoughtfully conceived and marketed. “U.S. News and World Report sells access to school rankings and other detailed college data. Consumer Reports gets paid for rating refrigerators. Congressional Quarterly sells high-priced, inside-the-Beltway dope. The New Yorker makes money off reprints of its cartoons. Millions are spent on Kindle books, iPhone applications and even ring tones. “The Wall Street Journal, which claims more than 1 million paid subscribers to its website, is the most notable among newspapers in charging for access to some of its content. How does it get away with charging, when so much business information is available for free from places like Yahoo Finance and 24/7 Wall St.? “The answer is: Original, authoritative reporting and the power of its brand. “Notwithstanding the recent layoff of a small percentage of its staff, the Journal continues reporting at essentially full force to get ahead of and behind complex stories involving business, investing and the economy. “The Journal’s generally reliable and insightful reporting – which is flashed immediately across a variety of interactive and mobile platforms – provides critical and actionable information to executives, investors and policy makers. To steal an old tag line from Forbes, it is an indispensable capitalist tool. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 2: You are: RUPERT MURDOCH The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 “By aggregating an audience of business people willing and able to pay to view its content, the Journal also has created a premium audience for advertisers, who pay top dollar to reach it. Thus, selling content reaps the additional benefit of boosting ad revenees. “The Journal isn’t the only newspaper charging for content. You also hit pay walls at places like the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette and the Santa Barbara NewsPress. But the story is different in each place. “Walter E. Hussman, the publisher of the Little Rock paper, admitted in a recent email to being on the “wrong side” of the paid-content debate for more than decade. And he couldn’t be happier. “I think the most compelling argument [for charging for content] is our paid circulation,” he said, noting that his average daily sale of 176,275 was 1.7% higher in 2008 than it was 10 years earlier. This contrasts starkly with the sharp circulation plunge suffered by the rest of the industry in the last decade. “Like the publishers of many small and medium papers, Hussman is fortunate to have scant competition in his market. With by far the largest force of reporters covering Arkansas, his paper is a must-read for anyone who wants to know what is happening in the state. “As long as the Gazette continues to publish exclusive and authoritative local news, Hussman can continue charging for access to his site. His ability to charge, it should be emphasized, is what helps support the production of the valuable content that gives his brand an unfair advantage over any would-be competitor. “By contrast, the Santa Barbara News-Press is living proof that geography and a long-standing franchise won’t let a publisher successfully charge for content that isn’t perceived by readers as being unique and valuable: “While the News-Press could scarcely be more isolated from California’s several large media markets, its for-pay website has been overtaken by a free site operated by the upstart Santa Barbara Independent. “The 53,817 unique visitors to the Independent site in January were more than double the traffic at the News-Press site, according to Compete.Com. In the last year, significantly, the Independent’s traffic rocketed by 48% while the News-Press audience fell 10% in the same period. “The weakness of the News-Press web strategy was revealed during the devastating fire in November that destroyed more than 100 homes. Scant information on the fast-moving blaze was available for non-subscribers at the News-Press site. At the same time, however, the Independent.Com brimmed with up-to-the-minute bulletins, first-person reports and even fire photos emailed from a Santa Barbara resident to his brother in Ohio, who posted them on the site because the California brother had lost his Internet connection. “The lesson here is not that free content trumps pay (though, all things being equal, it will) but that there has to be much more to a pay strategy than a publisher’s desire to want to be paid. This goes double when the publisher has been giving his valuable content away for free for the better part of two decades, as most newspapers have done. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 2: You are: RUPERT MURDOCH The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 “The trick to charging for content, therefore, is coming up with unique and valuable information that people will pay for. The converse is to let information be free that ought to be free. Things, for example, like the life threatening community emergency in Santa Barbara. … “Paid content doesn’t have to be business-oriented. It simply has to scratch the itch of a large enough niche of readers to make it worthwhile to produce the content. “Although the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel provides plenty of free coverage of the Green Bay Packers, the paper for years also has published a premium “Packer Insider” newsletter. Judging from the enormous number of people you see at Packer games wearing $17.95 plastic cheese wedges on their heads (not to mention the $34.95 cheese bra), the team should have at least 25,000 die-hard fans willing to shell out $44.95 annually for the newsletter. Assuming there are, the newsletter would be grossing more than $1 million a year. “The biggest mistake a newspaper can make is to cheap out on premium content. A few years ago, the Sacramento Bee tried selling an expensive newsletter that promised a wealth of exclusive insider news from the state’s capital. It should have been a hit. “Instead of profound insights, exclusive tips and actionable information, however, it was padded with things like the governor’s schedule for the next day. So, the newsletter flopped. Not because people won’t pay for content but because it failed to deliver enough unique, authoritative and actionable information to merit a premium price. “If you happen to be a publisher wrestling with how to move from free to paid content, don’t let anyone tell you that you can’t charge for it. If it’s good enough, readers will pay. If you attract the right audience, advertisers will pay, too. …” —Alan Mutter, Journalism and Technology Consultant (March 1-2, 2009) http://newsosaur.blogspot.com/2009/03/why-media-must-charge-for-webcontent.html FOR DISCUSSION General: Will the model work? How will it affect your persona’s enterprise? How will it affect web infrastructure? How will it affect web-related industry in general? How will it affect content itself? This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 2: You are: RUPERT MURDOCH The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 How will it affect content professionals? Specific: Is there a difference between the kinds of content users will pay for and the kinds they won’t? Would the pay firewall model require a collective shift across the entire news publishing industry? Has anybody thought about whether that would constitute illegal price-fixing? What makes the Wall Street Journal a successful model? What happened when the NYT tried it? Does Rupert Murdoch care about anything but Rupert Murdoch? This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 3: You are: GOOGLE The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 YOU ARE: GOOGLE Position: Users must pay, but not at the expense of searchable content. Revenue model: Micropayments “How to Save Your Newspaper” TIME Online “During the past few months, the crisis in journalism has reached meltdown proportions. It is now possible to contemplate a time when some major cities will no longer have a newspaper and when magazines and network-news operations will employ no more than a handful of reporters. “There is, however, a striking and somewhat odd fact about this crisis. Newspapers have more readers than ever. Their content, as well as that of newsmagazines and other producers of traditional journalism, is more popular than ever — even (in fact, especially) among young people. “The problem is that fewer of these consumers are paying. Instead, news organizations are merrily giving away their news. According to a Pew Research Center study, a tipping point occurred last year: more people in the U.S. got their news online for free than paid for it by buying newspapers and magazines. Who can blame them? Even an old print junkie like me has quit subscribing to the New York Times, because if it doesn't see fit to charge for its content, I'd feel like a fool paying for it. “This is not a business model that makes sense. Perhaps it appeared to [be] when Web advertising was booming and every half-sentient publisher could pretend to be among the clan who "got it" by chanting the mantra that the adsupported Web was "the future." But when Web advertising declined in the fourth quarter of 2008, free felt like the future of journalism only in the sense that a steep cliff is the future for a herd of lemmings…. “Newspapers and magazines traditionally have had three revenue sources: newsstand sales, subscriptions and advertising. The new business model relies only on the last of these. That makes for a wobbly stool even when the one leg is strong. When it weakens — as countless publishers have seen happen as a result of the recession — the stool can't possibly stand. “Henry Luce, a co-founder of TIME, disdained the notion of giveaway publications that relied solely on ad revenue. He called that formula ‘morally abhorrent’ and also ‘economically self-defeating.’ That was because he believed that good journalism required that a publication's primary duty be to its readers, not to its advertisers. In an advertising-only revenue model, the incentive is perverse. It is also self-defeating, because eventually you will weaken your bond with your readers if you do not feel directly dependent on them for your revenue. When a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, Dr. Johnson said, it concentrates his mind wonderfully. Journalism's fortnight is upon us, and I suspect that 2009 will be remembered as the year news organizations realized that further rounds of cost-cutting would not stave off the hangman…. “One option for survival being tried by some publications, such as the Christian Science Monitor and the Detroit Free Press, is to eliminate or drastically cut their print editions and focus on their free websites. Others may try to ride out the long winter, hope that their competitors die and pray This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 3: You are: GOOGLE The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 that they will grab a large enough share of advertising to make a profitable go of it as free sites. That's fine. We need a variety of competing strategies. “These approaches, however, still make a publication completely beholden to its advertisers. So I am hoping that this year will see the dawn of a bold, old idea that will provide yet another option that some news organizations might choose: getting paid by users for the services they provide and the journalism they produce. “This notion of charging for content is an old idea not simply because newspapers and magazines have been doing it for more than four centuries. It's also something they used to do at the dawn of the online era, in the early 1990s. Back then there were a passel of online service companies, such as Prodigy, CompuServe, Delphi and AOL. They used to charge users for the minutes people spent online, and it was naturally in their interest to keep the users online for as long as possible. As a result, good content was valued. When I was in charge of TIME's nascent online-media department back then, every year or so we would play off AOL and CompuServe; one year the bidding for our magazine and bulletin boards reached $1 million. “Then along came tools that made it easier for publications and users to venture onto the open Internet rather than remain in the walled gardens created by the online services. I remember talking to Louis Rossetto, then the editor of Wired, about ways to put our magazines directly online, and we decided that the best strategy was to use the hypertext markup language and transfer protocols that defined the World Wide Web. Wired and TIME made the plunge the same week in 1994, and within a year most other publications had done so as well. We invented things like banner ads that brought in a rising tide of revenue, but the upshot was that we abandoned getting paid for content. “One of history's ironies is that hypertext — an embedded Web link that refers you to another page or site — had been invented by Ted Nelson in the early 1960s with the goal of enabling micropayments for content. He wanted to make sure that the people who created good stuff got rewarded for it. In his vision, all links on a page would facilitate the accrual of small, automatic payments for whatever content was accessed. Instead, the Web got caught up in the ethos that information wants to be free. Others smarter than we were had avoided that trap. For example, when Bill Gates noticed in 1976 that hobbyists were freely sharing Altair BASIC, a code he and his colleagues had written, he sent an open letter to members of the Homebrew Computer Club telling them to stop. ‘One thing you do is prevent good software from being written,’ he railed. ‘Who can afford to do professional work for nothing?’ “The easy Internet ad dollars of the late 1990s enticed newspapers and magazines to put all of their content, plus a whole lot of blogs and whistles, onto their websites for free. But the bulk of the ad dollars has ended up flowing to groups that did not actually create much content but instead piggybacked on it: search engines, portals and some aggregators. “Another group that benefits from free journalism is Internet service providers. They get to charge customers $20 to $30 a month for access to the Web's trove of free content and services. As a result, it is not in their interest to facilitate easy ways for media creators to charge for their content. Thus we have a world in which phone companies have accustomed kids to paying up to 20 cents when they send a text message but it seems technologically and psychologically impossible to get people to pay 10 cents for a magazine, newspaper or newscast. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 3: You are: GOOGLE The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 “Currently a few newspapers, most notably the Wall Street Journal, charge for their online editions by requiring a monthly subscription. When Rupert Murdoch acquired the Journal, he ruminated publicly about dropping the fee. But Murdoch is, above all, a smart businessman. He took a look at the economics and decided it was lunacy to forgo the revenue — and that was even before the online ad market began contracting. Now his move looks really smart. Paid subscriptions for the Journal's website were up more than 7% in a very gloomy 2008. Plus, he spooked the New York Times into dropping its own halfhearted attempts to get subscription revenue, which were based on the (I think flawed) premise that it should charge for the paper's punditry rather than for its great reporting. (Author's note: After publication the New York Times vehemently denied that their thinking was influenced by outside considerations; I accept their explanation.) “But I don't think that subscriptions will solve everything — nor should they be the only way to charge for content. A person who wants one day's edition of a newspaper or is enticed by a link to an interesting article is rarely going to go through the cost and hassle of signing up for a subscription under today's clunky payment systems. The key to attracting online revenue, I think, is to come up with an iTunes-easy method of micropayment. We need something like digital coins or an E-ZPass digital wallet — a one-click system with a really simple interface that will permit impulse purchases of a newspaper, magazine, article, blog or video for a penny, nickel, dime or whatever the creator chooses to charge. “Admittedly, the Internet is littered with failed micropayment companies. If you remember Flooz, Beenz, CyberCash, Bitpass, Peppercoin and DigiCash, it's probably because you lost money investing in them. Many tracts and blog entries have been written about how the concept can't work because of bad tech or mental transaction costs. “But things have changed. ‘With newspapers entering bankruptcy even as their audience grows, the threat is not just to the companies that own them, but also to the news itself,’ wrote the savvy New York Times columnist David Carr last month in a column endorsing the idea of paid content. This creates a necessity that ought to be the mother of invention. In addition, our two most creative digital innovators have shown that a pay-per-drink model can work when it's made easy enough: Steve Jobs got music consumers (of all people) comfortable with the concept of paying 99 cents for a tune instead of Napsterizing an entire industry, and Jeff Bezos with his Kindle showed that consumers would buy electronic versions of books, magazines and newspapers if purchases could be done simply. (See Apple's 10 best business moves.) “What Internet payment options are there today? PayPal is the most famous, but it has transaction costs too high for impulse buys of less than a dollar. The denizens of Facebook are embracing systems like Spare Change, which allows them to charge their PayPal accounts or credit cards to get digital currency they can spend in small amounts. Similar services include Bee-Tokens and Tipjoy. Twitter users have Twitpay, which is a micropayment service for the micromessaging set. Gamers have their own digital currencies that can be used for impulse buys during online role-playing games. And real-world commuters are used to gizmos like E-ZPass, which deducts automatically from their prepaid account as they glide through a highway tollbooth. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 3: You are: GOOGLE The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 “Under a micropayment system, a newspaper might decide to charge a nickel for an article or a dime for that day's full edition or $2 for a month's worth of Web access. Some surfers would balk, but I suspect most would merrily click through if it were cheap and easy enough. “The system could be used for all forms of media: magazines and blogs, games and apps, TV newscasts and amateur videos, porn pictures and policy monographs, the reports of citizen journalists, recipes of great cooks and songs of garage bands. This would not only offer a lifeline to traditional media outlets but also nourish citizen journalists and bloggers. They have vastly enriched our realms of information and ideas, but most can't make much money at it. As a result, they tend to do it for the ego kick or as a civic contribution. A micropayment system would allow regular folks, the types who have to worry about feeding their families, to supplement their income by doing citizen journalism that is of value to their community. “When I used to go fishing in the bayous of Louisiana as a boy, my friend Thomas would sometimes steal ice from those machines outside gas stations. He had the theory that ice should be free. We didn't reflect much on who would make the ice if it were free, but fortunately we grew out of that phase. Likewise, those who believe that all content should be free should reflect on who will open bureaus in Baghdad or be able to fly off as freelancers to report in Rwanda under such a system. “I say this not because I am ‘evil,’ which is the description my daughter slings at those who want to charge for their Web content, music or apps. Instead, I say this because my daughter is very creative, and when she gets older, I want her to get paid for producing really neat stuff rather than come to me for money or decide that it makes more sense to be an investment banker. “I say this, too, because I love journalism. I think it is valuable and should be valued by its consumers. Charging for content forces discipline on journalists: they must produce things that people actually value. I suspect we will find that this necessity is actually liberating. The need to be valued by readers — serving them first and foremost rather than relying solely on advertising revenue — will allow the media once again to set their compass true to what journalism should always be about.” —Walter Isaacson, former managing editor of TIME, president and CEO of the Aspen Institute and author, most recently, of Einstein: His Life and Universe (Time online, 2/5/2009) http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1877191,00.html?iid=sphereinline-sidebar FOR DISCUSSION General: Will the model work? How will it affect your persona’s enterprise? How will it affect web infrastructure? How will it affect web-related industry in general? This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 3: You are: GOOGLE How will it affect content itself? How will it affect content professionals? The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 Specific: Can editorial content be compared directly to the content sold on iTunes? Does this article betray any underlying assumptions about content creation or content professionals? What are the implications for content strategy? Is Google going to take over the universe? Or just the known universe? This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 4: You are: MALCOLM GLADWELL The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 YOU ARE: MALCOLM GLADWELL Position: Users must pay. Content providers must innovate. Revenue model: Under construction. “Newspaper web sites must shift their primary focus from connecting people-tocontent to connecting people-to-people first, a.k.a. social networking. This is how news is going to get consumed as well as generate new revenue. Will this revenue support the current newsrooms? Highly unlikely. News organizations need to restructure. Many are being forced to through layoffs. “We need creative minds to think of new ways to monetize the changing media landscape. Attempts to setup pay walls is nothing more than last gasp efforts to retain a dying business model in a new media world.” —Eric Kaiser, Director of New Media Development, Sun Journal/Sun Media Group (March 9, 2009) http://erickaiser.com/?p=98 Business Week — The Tech Beat “Edgeio's New Model for Paid Content” “Edgeio, a site that aggregates classified listings across the Internet, today is introducing a new way for content creators to sell their digital wares—and for publishers to distribute it and take a cut. Although some folks, such as Jeff Jarvis, are not big fans of paid content online, even he thinks the Silicon Valley startup’s ‘transactional classified’ has interesting potential. “Essentially, you’ll be able to view and then immediately buy premium content on a site, whether that’s a research report, a song, a video, or an event ticket, without leaving the site to pay for it. At the same time, other publishers, whether Web sites, Web stores, blogs or whatever, can provide a link to the content and take a cut of resulting sales. So Edgeio’s providing a way to distribute content much more widely than on a single site or store. A rock band, for instance, could enable the sale of an album through fan blogs, and the fans get a cut along the way to sweeten the deal. “Here’s how Edgeio CEO Keith Teare describes it: We are making it possible for valuable content to be made available for sale on any web site. The web site does not need to have an ecommerce system, or a billing system – edgeio takes care of both. We have two customers for whom we work to make this possible. Firstly a content creator who has paid content that they would like to sell and have distributed. The content creator comes to edgeio and tells us about their content and we give them the means of publishing it. Secondly a publisher, whose main goal is to add revenue to their web site. The publisher comes to edgeio and can choose to become a point of sale for any paid content that they wish to be associated with. Any web site in the world can now become a point of sale for the things they are passionate about. “And here’s how the revenue model works, so far: This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 4: You are: MALCOLM GLADWELL The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 Edgeio’s business model is to enable a three-way revenue share. Firstly edgeio itself takes 20% of all transactions. The content creator takes the other 80%. The content creator can choose to enable affiliates to become additional sales points for the content and can define how its 80% is split with an affiliate. In that case their content always appears with a “Resell this Item” link, allowing affiliates to sign up as additional points of sale. “As Jarvis notes, though, the most interesting part may be less the payment system than the new distribution system, a potentially viral way to get content out there well beyond the confines of a single Web site or store.” —Rob Hof, Silicon Valley bureau chief, BusinessWeek, 8/10/2009 http://blogs.businessweek.com/mt/mt-tb.cgi/7332.1412913873 Stop the Presses (Editor & Publisher) by Steve Outing “Forget Micropayments -- Here's a Far Better Idea for Monetizing Content…” … “There is a better way [than micropayments] for online publishers to get people to pay for their content -- and of the many recent articles about how the newspaper industry can get people to start paying for their content (since online advertising alone doesn't bring in enough money to support large newsrooms), I've yet to see any suggestions like a model that I learned about recently from a California start-up venture called Kachingle…. … “I don't know if Kachingle will be the company that becomes the giant of online content payments; a lot depends on the execution, and the inevitable competition. But I do believe that the patented model Kachingle represents can work, and that it will allow online publishers to earn money from users paying for content. Paradigm shift “To start with, publishers have to get over the idea that they are going to get paid directly by the user. For the vast majority of a news publisher's content, there can be no barriers before an article asking the user if he wants to pay a penny or a nickel, or buy a $2 monthly subscription, to read on. “The user must be given the option of whether to pay for a Web site's content (by financially supporting the site), or read it for free. I'm betting this one will be a tough pill to swallow for many industry executives with traditional media mindsets, but it's critical because it fits the culture, indeed the nature, of the Internet. Traditional micropayment schemes for online news content – ‘pay up or go elsewhere’ -- fight it, and thus are doomed to fail, in my view. “Newspaper executives also have to grasp the notion that few publishers will be able to get very many people to pay for their content specifically. The Wall Street Journal Online can do it, because many of its paid online subscribers This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 4: You are: MALCOLM GLADWELL The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 are businesspeople who can charge the subscription bill to their expense accounts. Most other newspapers will only be able to charge online users directly for truly premium content that is not replicated somewhere else -- for example, e-books and other high-value content that's not typical newspaper fare. “Newspapers probably can charge for some multi-platform personalized news and information services, if they're good enough and useful enough. But that's not charging for the content (the news), it's charging for the valuable service of individual customization. “Also perhaps hard to accept (but you have to): The online news consumer samples many brands, from the New York Times to Joe's Blog. Most online users visit many Web sites on a typical day, bouncing around the world of free content. They'll have a few media brands and bloggers that they visit regularly, but they also encounter new ones frequently, via the serendipitous link spotted when reading something from a known media brand, to the recommendation of a friend on Facebook or Twitter or e-mail. Your once-powerful newspaper brand doesn't mean as much as it used to, and to get paid for newspaper content online, it must become part of a giant pool of content that's financially supported en masse. “Think of it this way and you'll understand the core concept behind Kachingle: Just as online users currently pay an Internet provider $30 or more a month for their computers to access the Internet, and perhaps a monthly fee for all the music they want from a service like Rhapsody, they'll also pay a monthly fee for all the news and blog content on the Web. Only the last fee is voluntary, and it will be up to publishers to educate the public on the importance of paying for content online. (National Public Radio has been doing this for itself for decades. Now commercial news publishers and bloggers need to do it to benefit all of them, not just one entity.) “The next important point to grasp about the Kachingle model is that it allows individuals to financially support the online content providers that they like best. So if a newspaper wants to get paid for its content when a Web site visitor clicks through to one of its articles, it should ask that the visitor support the site via Kachingle. Kachingle specifics “I've explained some of the concepts -- now let's get to the specifics, best understood in list form. “The Web user experience: As you read news sites and blogs all over the Web, you'll start to see sites with Kachingle "medallions." You'll join Kachingle by registering (the sites you visit will probably encourage you to), and you'll agree to pay a monthly fee to support valuable online content from publishers and bloggers you like. When the service starts in beta, the monthly default fee will be $5, but ultimately you'll be able to set whatever amount you wish. You might decide that all the content you read on media sites and blogs for "free" is worth $1 a month because that's all you can afford, or perhaps you can give $100 a month. It's your decision, in the same way you decide how This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 4: You are: MALCOLM GLADWELL The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 much you give to National Public Radio stations during their regular pledge drives. You can ignore Kachingle's plea for you to pay a monthly fee for online news and blog content, just as you can choose to send nothing to the NPR station but still listen to it. You will be able to see any free content on any site that has a Kachingle medallion. If you are a paying Kachingle account holder, you'll sign in once per device (PC, laptop, smart phone) and be remembered. So anytime you visit a site that uses Kachingle, the Kachingle medallion will recognize you. As a Kachingle account holder, when you visit, say, NYTimes.com, the Kachingle medallion on its pages will ask if you'd like to support the site. If you do, you'll click the support button on the medallion, which means that some of the monthly fee you pay Kachingle will go to NYTimes.com. That site will always remember that you support it, but the medallion will allow you to rescind support with one click. You'll see Kachingle medallions on lots of sites (in theory). Click to support the ones you like, or don't, as you visit them. You may end up with, say, three newspaper Web sites, one magazine site, and 30 blogs that you want to support; at each of those you would have clicked the Kachingle support button once. Now what happens is that Kachingle tracks your Web site and blog visits over the month. If you visited NYTimes.com 30 times, Editorandpublisher.com 10 times, and the blog SteveOuting.com 10 times (but none of the other sites that you support), then NYTimes.com would get 60% of your monthly Kachingle fee, and Editorandpublisher.com and my blog would get 20% each. In other words, the money you spend on your monthly Kachingle account is allotted by how often you visit the sites you support, rather than every site you support getting an even split of your money. (You may click to support a blog, but then never return to it; that blog won't get any of your money other than for the initial visit.) Kachingle doesn't change the current Web experience. Most content remains free, and you can view it as always with no barriers or mental transaction costs. “The publisher experience: Any publisher can join Kachingle for free. You can be an individual blogger with 100 readers, or NYTimes.com. Participating publishers put a Kachingle "medallion" (or more than one) on their Web sites, typically in a right or left column and highly visible. (Simple: Sign up as a Kachingle publisher and add a code snippet to your site's template.) As people visit your site who are already Kachingle users, they will see a “Support” button on the Kachingle medallion. If they like your site or blog and want to contribute some of their monthly Kachingle fee to it, they'll click “Support.” Initially, Kachingle will count an individual user visiting your site as one point, even if he reads 10 stories in a session. The supported blog that's visited by the same user who only clicks on a single page also gets logged as one point. A more sophisticated tracking system that would split funds among publishers based on page counts rather than site visits is possible in the future, according to Typaldos. She says Kachingle wants to start with a very simple system for the user to get them used to what is a new concept: voluntarily paying for online content. But as the This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 4: You are: MALCOLM GLADWELL The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 service evolves, the company will create new algorithms that Kachinglers will be able to choose. For example, a user might prefer to have her money split based on number of pages viewed, rather than the simpler split between sites visited. A Kachingler might request that 80% of his money goes to news sites and 20% goes to blogs. There are lots of possibilities, but Kachingle with start with a simple fixed model. While Kachingle might appear to favor bloggers who have limited content over giant news Web sites with lots of content, Typaldos says one option for the larger sites is to use multiple Kachingle medallions. For example, NYTimes.com if it had a single medallion would only get credited 1 point per day for every visitor. But it could use different medallions on each of its many blogs and perhaps earn more. The trade-off would be in simplicity for the consumer. In the latter scenario, a Kachingler would choose to support (or become a fan of) different blogs within the site, rather than clicking a Kachingle medallion just once to initiate financial support for NYTimes.com as a whole. All the monthly user fees (or contributions) collected by Kachingle are dispersed to participating publishers based on Kachingle account holders' Web activity on sites that they support. Kachingle will take 20% of the fees to support its business. Publishers will promote Kachingle in different ways, depending on how aggressive they want to be. Some might have nothing but a Kachingle medallion and hope that their site visitors will support their site if they are already Kachingle account holders. Others may choose to be more assertive and use a pop-up box requesting that site users sign up for Kachingle and support the site. (Kachingle will have such a pop-up available in the future.) Of course, the latter choice may annoy and/or turn away some Web site visitors, so the decision on how aggressively you want to ask for support is one you'll want to take seriously. Kachingle is offering marketing advice to participating publishers. The publisher's site will not change in any way other than the added Kachingle medallion. Anyone can read the content, just as before, whether they are a Kachingle account holder or not, and whether they support your site via Kachingle or not. “As you can see, other than the initial effort of signing up for Kachingle and thus deciding to financially support online content, there is no mental transaction cost to the online user in visiting a news site or blog. Click, read, share any content as you've always done with no barriers in the way. The only mental effort expended is one time per Web site: Do I financially Support this site or not? If I support it, I make one click. … Publishers need to educate, market “The power of the system is in its many participants. [I]t will be important for any participating publisher to urge their users to sign up for a Kachingle account ($5 a month as things start up), and educate and persuade them of the importance that they (voluntarily) pay for online content. The trick -- and this is the part that traditional-thinking publishers will have trouble accepting -- is that you are not just asking users to support your content, you are asking them to support all the news and blog content online. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 4: You are: MALCOLM GLADWELL The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 “But if this bothers you, think about it for a minute. When you get your users to sign up for Kachingle and start paying for content, you're helping lots of other Web publishers. And as all those other Web publishers and bloggers encourage their users to sign up for Kachingle, they are helping your site earn more money. Call it the power of the commons. The winners are the blogs and Web sites with the best content and that attract the most visitors and fans. Newspaper sites can win at that game, right? “Also, there's the social networking aspect of the Kachingle service, which will use Facebook and Twitter, for instance, to spread the word. Let's take an example in which I’m a paying Kachingler and I click the medallion on Editorandpublisher.com to support it. Assuming I've approved this in my privacy settings, Kachingle will note that "Steve Outing just became a financial supporter of Editorandpublisher.com via Kachingle" (or wording along those lines) and post it to my Twitter feed and my Facebook news feed, for my followers and friends to see and be influenced by it. The Google factor “The new wave of micropayment promoters -- while genuine in their desire to save the jobs of journalists and stop the decline in the quality of journalism resulting from newspaper layoffs, cutbacks and bankruptcies -- is actually suggesting something that will dig an even deeper hole for the newspaper industry. “A significant problem with micropayments is that it walls off content and makes it difficult to share with others and spread it around the Web. If I like an article and promote it in one of my Twitter posts, many of the people will not read it if they encounter a pay demand even for 5 cents; it's a barrier that will turn many away, especially if to get to the article the prospective user first has to sign up for some content payment network account. If I've paid 5 cents to read an article and want to promote it to my social network friends or followers, will the URL that I share even work? Perhaps not if the publisher hasn't set up the system to account for that. Internet users from other countries may not be able to access the content at all because they can't sign up for the micropayment system. “And of course there's Google, and the various news and blog search services. Will they index your content if it's behind a micropayment pay wall? If Google can't point people to your content, you may as well not be on the Web. And you're out of business. You have an answer, now run with it “Recently, New York Times executive editor Bill Keller wrote in his column some answers from readers about why NYTimes.com doesn't charge for its content. (You'll recall its TimesSelect paid-content experiment with Op-Ed columnists and archives put on a subscription plan, which failed to bring in enough revenue so was scrapped for a return to free content, more readers and more ad dollars.) Keller said he favors the general idea of Times online content being paid for by consumers who value it, but leaves an open mind about what approach to take. … “I think that Keller and other newspaper editors, struggling to survive a nasty downturn in print revenues and unable to find a way to adequately replace them This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.] Content Strategy — New York City Group 4: You are: MALCOLM GLADWELL The Paid Content Debate 2/13/16 on the digital publishing side, would approve of the Kachingle approach. That is, if they can get their minds past the hurdle of the payment for their content being voluntary, and that their content payment is mixed up in the big pile of money with all sorts of publishers, down to the pajama blogger. Otherwise, the Kachingle approach addresses Keller's concerns about stifled traffic, search engines and fleeing advertisers. …” —Steve Outing, founder of Digital Media Test Kitchen at U Colorado Boulder, etc. (Editor & Publisher, 2/10/2009) http://www.editorandpublisher.com/eandp/columns/stopthepresses_display.jsp?vnu_ content_id=1003940234 FOR DISCUSSION General: Will the model work? How will it affect your persona’s enterprise? [For Malcolm Gladwell, discuss start-ups or new content distribution models generally.] How will it affect web infrastructure? How will it affect web-related industry in general? How will it affect content itself? How will it affect content professionals? Specific: What are the hidden agendas of these bloggers? Is there a theoretical relationship between the “social networking” or shared content model and the “content wants to be free” argument? Where does branded content fit in? Do users care about the sourcing of their content? Do they care about its reliability and accuracy? How do the revenue models affect content quality? Is Malcolm Gladwell really an intellectual? Or does he just talk a good game? This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. [Attribution: Elena Melendy, Nitid LLC. All source materials retain original rights.]