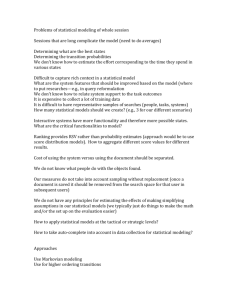

Abstract

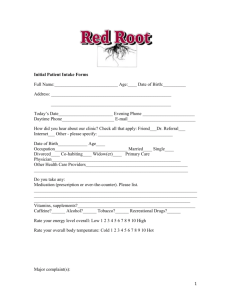

advertisement