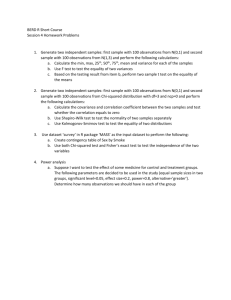

to DOC of full document

advertisement