An Audit of Attitudes Toward Diversity in a Hospital

advertisement

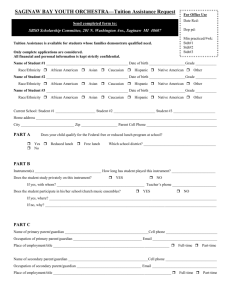

An Audit of Attitudes Toward Diversity in a Hospital Setting John P. Gaze, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Health Science and Business Administration Touro University International 5665 Plaza Drive Cypress, CA 90630 USA Phone: 904-451-4024 Email: JGaze@tourou.edu Jeffrey C. Bauer, D.B.A. Associate Professor of Management and Marketing University of Cincinnati-Clermont 4200 College Drive Batavia, Ohio 45103 USA Phone: 513-732-5257 E-mail: jeff.bauer@uc.edu An Audit of Attitudes Toward Diversity in a Hospital Setting ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to determine the extent to which employee receptivity of diversity and diversity management strategies varied by gender, and ethnicity. Employee attitudes toward diversity and diversity management were measured using previously established receptivity to diversity scales (Soni, 2000). The major findings of this study are: (1) Employees were receptive to diversity and diversity management; (2) Ethnic groups were found to differ on the measures given with: (2a) Male Asian Americans reporting significantly more receptivity to both diversity and diversity management than Caucasians, and (2b) Hispanics reporting more receptivity to diversity management than Caucasians. Key Words: Diversity, Diversity Management, Organizational Design/Development INTRODUCTION A recent review (2007) of company web sites revealed that there is movement by many U.S. organizations of all types (for example, Ford, 3M, IBM, Stanford Hospital and Clinics, and Duke University Health System) to place more emphasis on valuing employee differences, and developing diversity management initiatives (policies and programs that benefit all employees regardless of differences for a common goal). The benefits of a diverse workforce are the topic of discussion in many organizations in a variety of industries. At the same time, organizations are faced with understanding the importance of valuing differences and instituting effective diversity management initiatives as counter-measures to protect themselves from such negative consequences as lawsuits, loss of competitive advantage and diminished legitimacy in the eyes of the customers they serve. The increase in females and racial minority entrants in the work force, along with employers’ concerns about motivating and obtaining satisfactory levels of performance from a diverse group of employees, has created an urgency to understand and recognize the value of differences (Soni, 2000). Although literature on diversity has increased, few healthcare management articles have published original research on the subject of racial and ethnic diversity (Dreachslin, Jimpson, Sprainer & Evans, 2001). The extant literature suggests mixed corporate attitudes toward the philosophy of valuing differences. Historically, several companies have implemented a variety of initiatives for effectively utilizing and managing the current and projected diverse work force, but there are still some that have shown less interest in diversity issues. According to Gilbert, Stead, and Ivancevich (1999), the Avon Corporation implemented awareness training at all levels of the organization. It formed a multicultural participation council, which included the Chief Executive Officer (CEO), other high-ranking officials of Avon as well as minority employees. On the other hand, a survey of 1,406 U.S. companies by the Hay Group (1992) found that more than 60 percent of the respondents reported that they felt diversity was either not very important or not a high priority for the next two years. In the health care industry specifically, Dansky, Weech-Maldonado, DeSouza, & Dreachslin (2003) suggest that health care organizations have been especially slow in implementing diversity management programs. Nonetheless, several researchers (Gentile, 1994; Loden & Rosener, 1991; Thomas, 1991) have reported that gender and ethnic differences continue to have a significant effect on the treatment and experiences of people in the work place. The basic problem is that diversity management strategies call for attention to differences; attention that previous initiatives such as affirmative action and equal opportunity practices have tended to be adopted for symbolic purposes (Konrad & Linnehan, 1995). Present diversity management strategies require people to recognize, respect and celebrate a culture’s unique identity, customs and traditions; yet avoid overemphasizing these differences (negative stereotypes) or offering disparate treatment based on them. As such, diversity management initiatives require a distinction that can prove more subtle and potentially controversial in practice than in theory. LITERATURE REVIEW The Diversity Management Movement Shaped by changes in workforce demographics and legislation (Civil Rights Act, 1964 & Equal Employment Opportunity Act, 1972), U.S. Employment practices have evolved in response to numerous factors. While these initially involved legal requirements, moral responsibilities, and responses to internal and external group pressures (Williams & Bauer, 1994), consultants, scholars, and top executives have increasingly advocated the “valuing differences” approach to enhance organizational effectiveness (Cox & Blake, 1991). Valuing differences refers to an appreciation of differences and the creation of an environment in which everyone feels valued and accepted (Svehla, 1994). The motive for diversity management now stems more from the fact that in a global economy, workforce diversity is a reality requiring proper management to achieve organizational effectiveness (Williams & Bauer, 1994). Diversity management is concerned with planning and implementing organizational systems and practices to manage people so that the potential advantages are maximized (Cox, 1993). Despite the acclaim such management strategies have received by scholars and managers, whether employees value differences and support diversity management initiatives remains unclear. There has been a great deal of research on the sources of inequality; however, little has been done on the efficacy of different programs for countering it (Kalev, Dobbin, & Kelly, 2006). What is known is that diversity management has been considered by mainstream business organizations like the Society for Human Resource Management to be a legitimate sub-field of human resources management (Kelly & Dobbin, 1998). This paradigm (Giraldo, 1991,) moves beyond a human resource model based solely on legal compliance to one that suggests there is an inherent value in diversity. By the early 1990s, diversity management initiatives were adopted by 70 percent of Fortune 500 companies (Wheeler, 1994). However, the prevalence appeared to be lower among smaller companies (Kelly & Dobbin, 1998). This management trend has continued in recent years (Gathers, 2003), and organizations have had ample guidance in transforming their Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) and/or Affirmative Action (AA) activities into diversity programs in the form of articles, books, videos, conferences, newsletters and a growing cadre of organizational consultants (Kelly & Dobbin, 1998). Characteristics of diversity management initiatives were similar to those of EEO/AA practices. Practices included mission statements, diversity action plans, accountability for meeting diversity goals, employee involvement, career development and planning, diversity education and training, and long-term initiatives directed at cultural change within the workplace (Wheeler, 1994). The link between diversity and EEO/AA measures is confirmed by one of the new diversity practices, diversity training. In the narrow sense, diversity training is about compliance, (e.g., EEO, AA and sexual harassment). Although there is strong sentiment that diversity moves far beyond compliance, at this point, practices demonstrate a strong link between the two (Wheeler, 1994). Councils and advocacy groups have become popular in organizations promoting diversity management initiatives as well. For example, The IBM Company constituted a global workforce council to foster and promote diversity management. The council identified five issues to address, which are cultural awareness and acceptance, multilingualism, diversity of the management team, the advancement of women and workplace flexibility and balance. In addition, eight task forces were established to optimize satisfaction, productivity and creativity. These task forces were made up of various gender and ethnic groups. Training has been one of the more popular diversity management tools for organizations over the last several years. Diversity training includes a wide range of training sessions both in type and frequency. For example, Johns Hopkins Hospital conducted training on anti-discrimination law and a more personal cross-cultural communication class. The frequency of these classes ranges from one to two times each year. The most significant diversity tool in practice today is the audit. The audit utilizes surveys, interviews and focus groups (Thomas, 1991) to measure employee attitudes. Obtaining employee feedback on top diversity issues remains an important tool in healthcare organizations today (Gathers, 2003). However, attempts to change culture are costly long-term projects, especially newly developed initiatives, and therefore are much less common than repackaged EEO/AA measures (example, more compliance driven) that comprise the core diversity management (Kelly & Dobbin, 1998). One reason for this may be too many institutions are overwhelmed by too many healthcare challenges (Ruthledge & Wesley, 2001). The intent of diversity management is to create greater inclusion of all individuals into informal social networks and formal company programs (Sessa, 1992). Moreover, organizations want to ensure that an increasingly diverse group of employees will work together to achieve common goals (Eubanks, 1990). At present, diversity training and EEO/AA practices are performed on a less frequent basis than has been recommended by government polices. Benefits of Managing Diversity Muller and Haase (1994) describe managing diversity in terms of a manager being aware of the values and biases of his/her conventional management approaches, their ability and willingness to use employee focused strategies that affirm peoples’ differences while maintaining a high quality of productivity. Everett, Thorne and Danehower (1996) highlight the importance diversity training in their study of attitudes of men toward women in executive positions. This approach is a strategically driven process whose emphasis is on building specific skills and creating policies that bring out the best in everyone. Its goal is to create a level playing field through the assessment, identification and modeling of behaviors and policies that are seen as contributing to organizational goals (Svehla, 1994). Various benefits have been identified in the diversity literature and include: group performance, organizational performance, profitability, and employee awareness. More specifically, diversity has been linked to an increase in the quality of group performance, creativity of ideas, cooperation and the number of perspectives and alternatives considered (Cox, Lobel & McLeod, 1991; Watson, Kumar & Michalesen, 1993). The synergy model of managing diversity assumes that diverse groups will create new ways of working together effectively in a pluralistic environment. However, resistance due to denial of demographic changes and recognition of the need for and the benefits of a program can quickly derail any efforts to implement and sustain managing diversity efforts (Svehla, 1994). Progress Towards Managing Diversity Diversity has been said to improve tolerance and understanding of differences, supposedly resulting in positive outcomes including heightened group commitment and individual employee satisfaction (Wise & Tschirhart, 2000). However, despite changing demographics of the work force and potential benefits of diversity management, U.S. organizations have made minimal progress toward promoting friendly, productive working relationships across cultural differences (Ivanevich & Gilbert, 2000). It should be noted that despite the increase in diversity literature in the 1990s, there are still too few empirical research studies in the healthcare management field (Dreachslin, et al., 2001). Moreover, only a limited number of studies have focused on the area of receptivity to diversity (employee attitudes toward diversity) and receptivity to diversity management initiatives (employee support for diversity management initiatives implemented by the employer) (Soni, 2000). Among the few studies in this area the focus has primarily been on gender and ethnicity differences in attitudes toward EEO/AA measures (Aguirre, Martinez & Hernandez, 1993; Bobo & Kluegel, 1993) rather than diversity management strategies. In one study, the emphasis on diversity within the organization and the role of AA programs was found to be a point of considerable disagreement between minority and majority samples (Triandis, Kurowski, Tecktiel & Chan, 1993). Women and minorities favored AA programs and favored stronger pro-affirmative action policies than did Caucasian males (Triandis et al., 1993). According to Weech-Maldonado, Dreachslin and Dansky (2002), research on diversity management strategies in healthcare organizations is scarce. Literature is also scare in the military, especially in military medicine. Although the Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute (DEOMI) conducts research and assists the military with climate surveys, their focus is limited to equal opportunity and equal employment opportunity. RESEARCH QUESTIONS Analysis of the above literature suggests that the available research should be extended, and the common body of knowledge on diversity and diversity management be enhanced. In testing a new theoretical model of receptivity to diversity, Soni (2000) did indeed find significant and meaningful differences in how Caucasian males and females, and minority males and females view diversity and diversity management initiatives. However, very little empirical evidence exists about whether or not organizational members within specific racial groups in fact subscribe to the value of diversity and employer supported diversity management initiatives. This study provides an opportunity to better understand Soni’s (2000) findings and their potential to be generalized in a new setting, by determining the extent to which employee receptivity to diversity and receptivity to diversity management initiatives varied by gender and ethnicity. Unlike the Soni (2000) study that collapsed the racial groups into majority (Caucasian) and minority (African American, Hispanic, etc.), this study enhanced these categories by treating each racial group as a separate category for analysis. Consequently, the research questions at the heart of this study were defined as follows: 1. To what extent does employee receptivity to diversity vary by gender and ethnicity? 2. To what extent does employee receptivity to diversity management initiatives vary by gender and ethnicity? METHODS Selection of Subjects The U.S. Navy Medical Treatment Facility’s (MTF) personnel breakdown is comparable to the population percentages of males, females, Whites, Blacks, Asians and Hispanics in the United States Air Force, Army and Navy, and therefore all 100 percent of the MTF population (894 government civilian employees and military service members) were chosen as study subjects, Demographically divided to: 510 males (57%), 384 females (43%); 393 Caucasians (44%), 244 Asian Americans (27%), 176 African American s (20%) and 80 Hispanics (9%). Research Instrumentation The survey instrument used in this study was developed using the receptivity to diversity factor conclusions drawn from Soni’s (2000) study. The items in each dimension were additively combined to create indexes reflecting the complex concepts. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the indexes ranged from 0.8 to 0.9. Content validity was used as the validity criterion for the instrument. The questions relating to receptivity to diversity and receptivity to diversity management initiatives were rated in the study using a 1-5 Likert scale format, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. Data Collection Procedures An introductory cover letter containing the purpose of the study, a request for cooperation and promise of anonymity was mailed to each member of the organization. All surveys were sent to the mailbox of each member of the organization with a request to return the survey in 20 days. Measures taken to increase the survey response rate included two email reminders and a pledge by the researcher to donate $1.00 U.S. dollar to a local orphanage for every completed survey received. All responses were returned on a voluntary basis, so subjects were not influenced or coerced in any way. Data Analysis Univariate Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the relationships between: Receptivity to diversity and gender/ethnicity, (i.e., whether receptivity scores varied significantly by gender/ethnicity) Receptivity to diversity management and gender/ethnicity, (i.e., whether receptivity scores varied significantly by gender/ethnicity) RESULTS Demographic Data A sound questionnaire response rate of 57% for males and 43% for females provided for a sample of 328 (224 male and 104 female) subjects broken down into the following ethnic groups: Caucasian: 140 (42.7%); Asian American: 86 (26.2%); African American: 67 (20.4%); Hispanic: 35 (10.7%) Statistical Analysis Tables 1 and 2 show the descriptive statistics and between-subjects effects for the dependent variable receptivity to diversity. As can be seen in Table 2 there was no main effect for gender, [F(1,320) = 2.862 (p = .092)] however, the result approached significance with males scoring slightly higher than females on receptivity to diversity (MFemales=3.55; MMales = 3.68). Table 1 Descriptive Statistics, Dependent Variable: Diversity Gender Ethnicity Mean Std. Deviation N Male Caucasian 3.5108 .5752 102 Asian American 4.0000 .5116 59 African American 3.6523 .5437 44 Hispanic 3.6895 .6732 19 Total 3.6826 .5932 224 Caucasian 3.4342 .5625 38 Asian American 3.5481 .5041 27 African American 3.5913 .4274 23 Hispanic 3.8000 .4211 16 Total 3.5548 .5076 104 Caucasian 3.4900 .5708 140 Asian American 3.8581 .5485 86 African American 3.6313 .5043 67 Hispanic 3.7400 .5668 35 Total 3.6421 .5698 328 Female Total Table 2 Univariate Analysis of Variance, Tests of Between-Subjects Effects; Dependent Variable: Receptivity to Diversity Source Type III Df Mean Sum of F Sig. Square Squares Corrected 11.702 7 1.672 5.664 .000 Intercept 3146.776 1 3146.776 10660.601 .000 GENDER .845 1 .845 2.862 .092 ETHNICITY 4.708 3 1.569 5.317 .001 GENDER X 2.546 3 .849 2.875 .036 Error 94.457 320 .295 Total 4456.980 328 Corrected 106.159 327 Model ETHNICITY Total As seen in Table 2, the 4 ethnic groups were found to differ significantly in receptivity to diversity [F(3, 320) = 5.317, P=.001]. A Bonferroni multiple comparisons procedure was conducted to determine which means were significantly different across ethnicity. As indicated in Table 3, Asian American employees were found to be significantly more receptive to diversity than Caucasian employees. The significant main effect for ethnicity was qualified by an interaction effect between gender and ethnicity whereby as a group male Asian American employees reported greater receptivity to diversity than Caucasian employees while female Asian American employees did not (see Figure 1). Table 3 Post Hoc (Bonferroni) Comparisons of Receptivity to Diversity by Racial Group Mean Std. Error (I) Ethnicity (J) Ethnicity Caucasian Asian Sig. 95% Difference Confidence (I-J) Interval Lower Bound Upper Bound -.3681*** 7.444E-02 .000 -.5657 -.1705 -.1413 8.071E-02 .485 -.3556 7.292E-02 -.2500 .093 -.5226 2.258E-02 .065 -8.2355E-03 .4618 American African American Hispanic Asian African American American African .1027 .2268 8.853E-02 Hispanic .1181 .1089 1.000 -.1710 .4073 Hispanic -.1087 .1133 1.000 -.4095 .1922 American *** = Significant at p<.001 Figure 1 Estimated Marginal Means for Receptivity to Diversity by Ethnicity 4.25 4 Caucasian Asian Am African Am Hispanic 3.75 3.5 3.25 Male Female Tables 4 and 5 show the descriptive statistics and between-subjects effects for the dependent variable receptivity to diversity management. As the F-Test and significance levels presented in Table 5 indicate, there was no significant difference between female and male employees’ receptivity to diversity management scores (MFemales=3.50; MMales = 3.52), F(1, 320) = .173, P=.678. Table 4 Descriptive Statistics, Dependent Variable: diversity management Gender Ethnicity Mean Std. N Deviation Male Caucasian 3.3765 .4285 102 Asian 3.7356 .4898 59 3.5341 .4759 44 Hispanic 3.6158 .5014 19 Total 3.5223 .4817 224 Caucasian 3.3658 .4634 38 Asian 3.4889 .3886 27 3.5783 .3849 23 Hispanic 3.7313 .4785 16 Total 3.5010 .4434 104 Caucasian 3.3736 .4366 140 Asian 3.6581 .4724 86 3.5493 .4443 67 Hispanic 3.6686 .4874 35 Total 3.5155 .4693 328 American African American Female American African American Total American African American Table 5 Univariate Analysis of Variance, Tests of Between-Subjects Effects Dependent Variable: Receptivity to Diversity Management Source Type III Sum df Mean Square F Sig. of Squares Corrected 6.742 7 .963 4.721 .000 Intercept 2976.850 1 2976.850 14590.477 .000 GENDER 3.520E-02 1 3.520E-02 .173 .678 ETHNICITY 3.966 3 1.322 6.480 .000 GENDER X 1.130 3 .377 1.846 .139 Error 65.289 320 .204 Total 4125.810 328 Model ETHNICITY Corrected 72.031 327 Total The ANOVA results presented in Table 5 indicate that receptivity to diversity management differed significantly across ethnicity F(3, 320) = 6.480, P<.001. A Bonferroni multiple comparisons procedure was conducted to determine which means were significantly different from one another (Table 6). The results revealed, that Asian Americans reported significantly greater receptivity to diversity management than their Caucasian co-workers. Statistically significant differences were also found between Hispanic and Caucasian employees (p = .004) with Hispanics being more receptive to diversity management. While not as disparate as the groups above, the difference in means between Caucasian and African American employees approached significance (p = .056). Table 6 Post Hoc (Bonferroni) Tests Ethnicity Multiple Comparisons Dependent Variable: Diversity management Mean Std. Difference (I- Error Sig. Confidence J) (I) Ethnicity (J) Ethnicity Caucasian Asian American African American Hispanic 95% Interval Lower Bound Upper Bound -.2846 *** 6.188E- .000 -.4489 -.1203 .056 -.3538 2.454E-03 .004 -.5216 -6.8384E-02 02 -.1757 6.710E02 -.2950 ** 8.536E02 Asian African American American Hispanic .1089 7.360E- .840 -8.6516E-02 .3043 02 -1.0432E-02 9.056E- 1.000 -.2509 .2300 -.3694 .1308 02 African Hispanic American -.1193 9.420E- 1.000 02 ** = Significant at <.01 *** = Significant at <.001 DISCUSSION Contrary to similar gender and ethnicity research (Soni, 2000), no significant difference was found between female and male employees in their receptivity to diversity. However, gender did mediate the impact of ethnicity on receptivity to diversity in that male Asian Americans reported significantly greater receptivity to diversity than Caucasians, while female Asian Americans did not. The lack of a significant main effect for gender on either dependent variable may represent a selection effect due to the military environment studied. Females that work in a male dominated environment such as the military may be those that have less traditionally feminine identities and thus don’t perceive the personal benefit of treating gender as a target for diversity management interventions. This lack of differences could also reflect the success of Navy medicine in promoting the work and value of female personnel. The absence of a gender finding could also be the leveling result of a rule oriented and compliance driven environment where mandated equal employment opportunity training and regular command climate evaluations are the norm. It is also arguable that recruit training and subsequent operational experiences provided by the U.S. Navy offer some of the most effective approaches to managing diversity seen in large organizations. The U.S. Navy builds cohesive units out of diverse groups of individuals during recruit training, emphasizing the importance of teamwork in overcoming obstacles. Strong bonds are often forged though overcoming shared adversity. Moreover, early on in the indoctrination to Navy life, personnel are taught a set of unified values more commonly referred to as core values (Honor, Courage and Commitment). It is suggested that these core values may moderate attitudinal differences based on gender and ethnicity. Such a team-oriented society may engender respect and appreciation for the unique skills and perspectives brought to bear on shared problems by team members from diverse backgrounds. As such, there may be a general level of acceptance and appreciation for diversity that mitigates most between-group differences. The benefits of these experiences may be limited however, as differences between racial groups became more amplified when receptivity to diversity management was examined. In other words the hypothesized respect for diversity inherent to the military culture may only go as far as leveling people’s openness to diversity but not to diversity management. When it came to endorsing diversity initiatives in the workplace, Hispanic and Asian American employees were significantly more receptive to these than Caucasian employees. A similar though non-statistically significant pattern was seen for African Americans compared to Caucasians. Still there is one question that needs to be reconciled. Why was the difference in receptivity to diversity more pronounced between Caucasian and Asian American employees as opposed to the other ethnic groups? This is an interesting finding since the literature (Kravitz & Platania, 1993; Bell, Harrison & McLaughlin, 1997; Bobo, 1998; Kravitz & Klineberg, 2000) suggests that Asian American employees are generally less receptive to diversity than Hispanic and African American employees, but more receptive to diversity than Caucasian employees. Further information that may help explain this significant difference follows below. Most of the Asian Americans in the study were born in the Philippines. As a subpopulation within the category of Asian Americans they are likely to have unique characteristics, which warrant further study as a separate group. Additionally, a post survey interview of some of the Asian American employees revealed that some had past experiences with discrimination and value different cultures and heterogeneous teams. The location of the institutional setting in Okinawa, Japan also deserves mention. The embedding of a western-based institution in an eastern culture may have highlighted cultural differences that were more salient to Asian Americans than to other minorities. Lastly, qualitative data collected in the form of post survey interviews underscored the differences in the receptivity to diversity management means between Caucasian employees and Asian and Hispanic employees. Many Asian Americans and Hispanics reported that they thought diversity management policies and programs were necessary in the workplace. Some commented that programs “let people know they need to treat others fairly” and that “[the organization is] simply open to diversity.” In fact, some of respondents believed that diversity policies and programs assisted them with their advancement. LIMITATIONS This study expands our knowledge of diversity management in healthcare. However, there are a few noteworthy limitations. First, the Hispanic population in this study was small (80 or 9% of the hospital population) as this is part of the makeup of the organization. This may limit the generalization for that group in a similar setting. Next, there is some evidence to suggest that individuals can differ in the extent to which their group membership is central and salient to their self-concept (Luhtanen & Crocker, 1992; Markus & Kunda, 1986). Lastly, this study confined itself to surveying civilian and military members of an overseas U.S. Navy MTF and while the author believes this sample to be reasonably representative of other employee populations, caution is recommended in generalizing these findings to other settings. IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGERS There is a challenge for organizational leaders to influence everyone to want to work together as an effective and efficient team. As workplace diversity increases in organizations so will the possibility of problems among different cultures. Leaders who understand this upfront can help temper the adverse effects on the staff and on the organization as a whole. Hiring staff who value differences (especially leaders), focusing on team building, offering diversity training, developing policies and programs that recognize differences, but share a common goal towards unity, conducting periodic culture audits and sharing results with staff are all ways to improve receptivity to diversity and achieve and maintain diversity management. References 3M. (n.d.). Diversity at 3M. Retrieved on February 20, 2007 from http://solutions.3m.com/wps/portal/3M/en_US/us-diversity/diversity/ Aguirre, A., Martinez, R. & Hernandez, A. (1993). Majority and minority faculty perceptions in academia. Research in Higher Education, v34, 371-385. Bell, M., Harrison, D. & McLaughlin, M. (1997). Asian American attitudes toward affirmative action in employment: Implications for the model minority myth. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 33, 356-377. Bobo, L. & Kluegel, J. (1993). Opposition to race – targeting: Self-interest, stratification ideology, or racial attitudes? American Sociological Review, v58, 443- 464. Bobo, L. (1998). Race, interests, and beliefs about affirmative action. American Behavioral Scientist, 41, 985-1003. Cox, T. (1993). Cultural diversity in organizations: Theory, research & practice, San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler. Cox, T. & Blake, S. (1991). Managing cultural diversity: Implications for organizational competitiveness. The Executive, v5, i3, 45-55. Cox, T., Lobel, S. & McLeod, P. (1991). Effects of ethnic group cultural differences on cooperative and competitive behavior on a group task. Academy of Management Journal, v34, 827-847. Dansky, K., Weech-Maldonado, R., DeSouza, G., & Dreachslin, J. (2003). Organizational Strategy and Diversity Management: Diversity-Sensitive Orientation as a Moderating Influence. Health Care Management Review, v28(3), 243-253. Dreachslin, J., Jimpson, G, Sprainer, E. & Evans, R. (2001). Race, ethnicity, and careers in healthcare management/Practitioner response. Journal of Healthcare Management, v46, i6, 397-410. Duke University Health System. (n.d.). Diversity at Duke Hospital. Retrieved on February 20, 2007 from http://diversity.duhs.duke.edu/ Eubanks, P. (1990). Workforce diversity in healthcare: Managing the melting pot. Hospitals, 48-51. Everett, L., Thorne, D., & Danehower, C. (1996). Cognitive moral development and attitudes toward women executives. Journal of Business Ethics, v15, n11. Ford Motor Company. (n.d.). Valuing Diversity. Retrieved on February 20, 2007 from http://www.mycareer.ford.com/ONTHETEAM.ASP?CID=15 Gathers, D. (2003). Diversity Management: An Imperative for Healthcare Organizations. Hospital Topics, v81, i3, 14-21. Gentile, M. (1994). Differences that work. Boston: Harvard Business Review. Gilbert, J., Stead, B., & Ivancevich, J. (1999). Diversity management: A new organizational paradigm. Journal of Business Ethics, v21, n1. Giraldo, Z. (1991). Early efforts at achieving a diversified work force: Going beyond EEO/AA. In Gilbert, J., Stead, A. & Ivancevich, J. (1999). Diversity management: A new organizational paradigm. Journal of Business Ethics, v21, i1, 61-76. Hay Group Management Consulting Firm. (1992). Tensions keep focus on diversity issues. Working Together, 1, 10. IBM. (n.d.). Valuing Diversity. Retrieved on February 20, 2007 from http://www-03.ibm.com/employment/us/diverse/feature_nafe.shtml Ivancevich, J. & Gilbert, J. (2000). Diversity management. Public Personnel Management, v29, i1, 75-93. Kalev, A., Dobbin, F., & Kelly, E. (2006). Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. American Sociological Review, v71. Kelly, E. & Dobbin, F. (1998). How affirmative action became diversity management. American Behavioral Scientist, v41, i7, p960-985. Konrad, A. & Linnehan, F. (1995). Formalized HRM Structures: Coordinating Equal Employment Opportunity or Concealing Organizational Practices? The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 38, No. 3 Kravitz, D. & Klineberg, S. (2000). Reactions to two versions of affirmative action among White, Blacks, and Hispanics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 597-611. Kravitz, D. & Platania, J. (1993). Attitudes and beliefs about affirmative action: Effects of target and of respondent sex and ethnicity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 928-938. Loden, M. & Rosener, J. (1991). Workforce America! Managing employee diversity as a vital resource. Homewood, IL: Business One-Irwin. Muller, H. & Haase, B. (1994). Managing diversity in health services organizations. Hospital & Health Services Administration, v39, i4, 415-424. Ruthledge, E. & Wesley, N. (2001). The struggle for equality in healthcare continues. Journal of Healthcare Management, v46, i5, 313-325. Sessa, V. (1992). Managing diversity at the Xerox corporation: Balanced work force goals and caucus groups. In Gilbert, J., Stead, A. & Ivancevich, J. (1999). Diversity management: A new organizational paradigm. Journal of Business Ethics, v21, i1, 61-76. Soni, V. (2000). A twenty-first century reception for diversity in the public sector: A case study. Public Administration Review, v60, i5, 395-403. Stanford Hospitals and Clinics. (n.d.). Managing and valuing diversity and inclusion. Retrieved on February 20, 2007 from http://www.stanfordhospital.com/newsEvents/eventsLectures/2005/1005/ceManage Div Svehla, T. (1994). Diversity management: Key to future success. Frontiers of Health Services Management, v11, no2, 3-34. Thomas, R. (1991). Beyond race and gender: Unleashing the power of your total work force by managing diversity, New York: AMACOM. Triandis, H., Kurowski, L., Tecktiel, A. & Chan, D. (1993). Extracting the emics of diversity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, v17, 217-234. Watson, W., Kumar, K. & Michaelsen, L. (1993). Cultural diversity's impact on interaction process and performance: Comparing homogeneous and diverse task groups. Academy of Management Journal, v36, 590-602. Weech-Maldonado, R., Dreachslin, J. & Dansky, K. (2002). Racial/ethnic diversity management and culture competency: The case of Pennsylvania hospitals/Practitioner application. Journal of Healthcare Management, v47, i2, 111126. Wheeler, M. (1994). Diversity training: A research report. New York: The Conference Board. Williams, M. & Bauer, T. (1994). The effect of a managing diversity policy on organizational attractiveness. Group & Organization Management, v19, n3, 295309. Wise, L. & Tschirhart, M. (2000). Examining empirical evidence on diversity effects: How useful is diversity research for public-sector managers? Public Administration Review, v60, n5, 386-395.