Read more - Cal Poly Pomona

advertisement

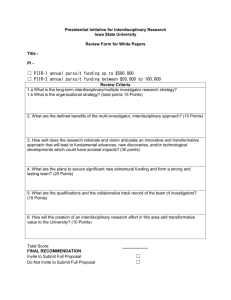

CAL POLY, POMONA DESIGN BASED LEARNING DELIVERS REQUIRED STANDARDS IN ALL SUBJECTS, K-12 Professor Doreen Nelson Teachers find that by using a small activity to ignite their students’ curiosity they can speed up their students’ learning while solving problems of curriculum overload and classroom behavior. Design Based Learning provides a concrete method for teaching and evaluating students that integrates the required K-12 curriculum. It uses techniques from the design professions to form a methodology that challenges students to design hands-on solutions to problems in simulated experiences. As students develop Never-Before-Seen solutions for businesses, cities, villages, or civilizations they learn to think critically. They apply the lessons from textbooks that address the required academic standards. Introduction In all walks of American life there are students who are so turned off to learning that they are not paying attention at school and sometimes not going to school, altogether. Teachers are overwhelmed with all they are required to monitor. Teaching to the tests leads to burnout for them and for their students. Both English Language Learners and English speakers are struggling with basic English fluency skills. Learning Handicapped (L-H) students are lacking the academic confidence needed to enter standard classrooms. Even those learning the skills of reading, listening, speaking, and reasoning, cannot extrapolate information from stories they have read. Disruptive students eat away at classroom time, unable to remain ontask in both individual and group efforts. With all of the in-services and legislation not much has changed except that in the rush to teach to the standards, critical thinking has been lost from the curriculum. In the late 19th century John Dewey described the importance of learning by doing. He believed in the act of discovery and original thought and he rejected replicative learning. In K-12 classrooms Design Based Learning (DBL), an outgrowth of Dewey’s methods, gives teachers a blueprint to teach critical thinking that gets results on standardized tests. By continuing in Dewey’s tradition - and adding a strong Published in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 17, Fall 2004 California Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA 1 evaluation component - DBL provides a way to unify the classroom and to evaluate student progress that meets academic standards. Design Based Learning delivers any required K-12 curriculum by challenging students to design hands-on solutions to problems in simulated experiences. A teacher may focus on building Never-Before-Seen businesses, cities, villages, or civilizations. Based on real places in the future, students develop Never-Before-Seen solutions. Whatever they build becomes a starting point for entering academic lessons as the students compare their designs to what they read about. Criteria are set for each activity as a built-in evaluation process as a rubric for grading. Students learn to set and use criteria. They are graded on their ability to think critically as they develop proposals for solving problems. By creating a tactile experience with a monitoring technique the students have fun, remember what they learned, and can transfer it to other situations. In each of the researched classrooms presented here, students were immersed in Design Based Learning. Across the board they excelled on standardized tests. Those students at the lower end of the testing scale, those with learning disabilities and those usually unable to succeed far surpassed their own previous test scores. They made leaps of 10 to 20 percent. The traditional ‘higher achievers’ continue to accelerate though not at such a dramatic rate. An Example Emily Tilton, a sixth grade Language Arts teacher in La Puente, California, motivated her English Language Learner students to master the test materials. She started using Design Based Learning in 2000 to teach them how to deliver presentations. Once they based their work on a design activity, building a NeverBefore-Seen Recyclable City that took 45 minutes away from instructional time, the investment paid-off with a flurry of persuasive, well-organized presentations. The students readily spent hours researching, writing about, and presenting their designs. Emily demystified the grading process by getting them to use criteria for self-evaluation. As a result, they excelled on the standardized tests and were having so much fun that they thought they were playing. The visual template below describes how Emily met her specific academic standards. She started her students with a design activity, then taught multiple lessons linked to the standards using textbooks, drill, and practice. The lines between the academic standards and the lessons indicate that all but those in the middle took place after the activity. Published in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 17, Fall 2004 California Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA 2 Standards Writing Strategies1.4 Organization and focus: identify topics, ask questions that lead to research. Reading Comp. 3.4 Identify and analyze recurring themes across works. Speaking App.2.0 - Deliver well organized formal presentations. Writing Strategies1.3 Organization and focus: use note taking, outlining, and summarizing to impose structure on drafts. Reading Comp. 2.1 - Understand differences of purpose in various categories of informational materials. Activity Build a Never Before Seen Recyclable City Lessons Share pieces of Recyclable City. Write goals for city committees. Read “Barrio Boy” p. 29. Discuss themes of new experiences, city living, friendship. Keep notes of committee meetings. Research on-line information about recycling. There are hundreds of teachers in California, New York, and across seven cities in Japan raising students’ test scores and meeting local and state requirements with Design Based Learning. Published in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 17, Fall 2004 California Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA 3 Presented here are four case studies from those teachers. The research collected in their classrooms gives a glimpse into how it works for a variety of grade levels and subject matter areas. These teachers each had their own motivations to seek out better teaching methods. Each felt overwhelmed with the many, varied demands that are put on them. Each wanted to have fun with their students and to make his or her own time in the classroom more fulfilling. Each wanted to teach the required information and have their students pass the tests. Case Studies Maria Teresa (Teri) Ceja, a 2nd grade teacher in La Puente, CA, started using Design Based Learning in 1998 after having taught for 12 years. Teri had three objectives when she changed her teaching method to Design Based Learning: to make students want to be at school, to teach them the English language, and to have them meet the required standards. Teri’s 2nd grade students’ test scores showed that for her lowest end students, Design Based Learning experiences produced marked improvements. Teri developed a Design Based Learning project called Creatureland. They started out backwards. Each week she led an activity in which her students role-played, set criteria, designed solutions to problems, and actually built their designs. They took on double personalities pretending to be everyday objects then invented a new cover for their body. They interviewed their object about what it liked, disliked, or feared and described who they were and why. Their verbal skills translated into written stories. Math skills became relevant as they measured themselves and their objects to compare ratios and proportions. Published in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 17, Fall 2004 California Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA 4 QuickTime™ and a GIF decompressor are needed to see this picture. As “creatures” these at-risk students from low-income households liked coming to school “to play”, significantly improving daily attendance rates. Once their object creatures were ‘born’, each located their family, friends, and natural predators. Sound Boy (radio) decided that Flashy Girl (camera) was his sister, as they are both communication tools. Water Boy (milk) who made things wet was a natural enemy to both. All of the creatures moved into a never-before-seen future city. They pretended to live on a physical landsite with their families and used natural resources (junk materials) to create shelters. They experienced the meaning of private and community ownership. They named and located necessary services. They tried out different governments for Creatureland. They made agendas and conducted town meetings to decide where to place structures in their community. They designed a Never-Before-Seen movement system for the city creatures. They compiled booklets to document the history of their activities. They produced puppet shows to learn to construct dialogue and drafted written and oral presentations for classroom visitor tours, identifying main ideas. All of these products were used as evidence for grading. Teri developed a curriculum that tied together many of the disconnected standards. She found it easier to communicate with parents, administrators, and students about expectations and evaluation. Leslie Stoltz, a 6th – 8th grade Social Studies and Language Arts teacher in Diamond Bar, CA, started using Design Based Learning in 1996 after having taught for 15 years. Leslie had five objectives when she began using Design Based Learning: to teach the required standards so that the variety of material added up to something memorable for the students; to team teach with and train her partner Mark Lantz, a Science teacher; to cover extensive material in their three subjects; to keep 70 students on-task over an extended time block; and to continue her own intellectual growth as a teacher. Published in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 17, Fall 2004 California Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA 5 Leslie’s students, from upper-middle to lower-middle income households, significantly strengthened their literacy skills - to read, listen, speak, and reason while making oral and written presentations. The students were divided into four quartiles with the lowest achievers being on the right. The lavender represents before DBL and the blue indicates the results after. Leslie used four separate landforms (approx. 4’ x 6’) with each representing the geographical features and climates of the ancient civilizations she was required to teach in Social Studies (Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Greece). Calling it Civilization Building, the students had to meet specific pre set criteria as they developed shelters, a division of labor, a government, a culture, and a communication and movement system for each culture. Instead of building Egypt, they were given the situation and problems which ancient Egyptians encountered. Calling themselves the Dune People, they built NeverBefore-Seen biomes, ways to move around and ways to live to eternity. If Leslie had shown them the pyramids they would have built replicas of them. Instead they made their own places for rites, rituals, and religion before studying the Pyramids. These built models helped students find the similarities and differences between their designs and those of the four historical cultures. The Mountain People (China), the Desert People (Mesopotamia), and the Seaside People (Greece) all had the same problems to solve, but each with different physical conditions. Leslie wondered when to tell her students what they were really studying. They liked pretending they were creating the first civilizations on earth, much like those that they were reading about in their texts. When she did tell them they said, “Yes, we knew we were studying Egypt, but our Egypt is better.” Now, six years later Leslie says it doesn’t matter when or even if you tell them, because they know. Design Based Learning put a stop to Leslie’s burnout. She now chooses to remain in the classroom and train other teachers. Published in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 17, Fall 2004 California Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA 6 Leslie developed her students’ problem-solving techniques by having them work on physical landsites in order to learn in a context. Her disruptive students were channeled to remain on-task in both individual and group efforts. Don Huey, a high school World History, Life Science, Governments, and U.S. History teacher in Pomona, CA, started using Design Based Learning in 1995 after having taught for 19 years. His Learning Handicapped (L-H) students gained heightened levels of confidence and many were able to enter standard classrooms. An autistic student was motivated to enter the Toyota Automobile of the Future Competition without additional coaching from the teacher. Don had two objectives when he began using Design Based Learning: to bring LH students up to grade level so they could mainstream into standard classrooms and to engage them with a variety of learning in academics. At the high school level, students spend shorter time periods with one teacher in core subjects. Unlike lower grades, they rarely construct artifacts that represent their learning. For Don’s L-H students, in particular, hands-on authentic learning is essential. His students created a Never-Before-Seen island continent called Newlandia. It was placed on a map of the world with an actual latitude, longitude, shape, and size. Each of the four classes created one-fourth of this new place according to Don’s criteria. They each set out to explore and develop it. The government students created a government for the new land and played the roles for activating it; the history students created an indigenous culture and built it; and the science students located the continent on the world map and then created the biomes, plants, and animals that originated there. They sent e-mails to each other with instructions and explanations for their choices. Don contends that this was the first time in his teaching career in which he found one method that reached the varied needs of all his students. Published in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 17, Fall 2004 California Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA 7 Where in the world is Newlandia? Grace Lim-Hays, a high school Literature teacher in Walnut, CA, started using Design Based Learning in 1996 after having taught for 4 years. Her middle-income students learned to extrapolate a wide variety of information from the stories they read. They had a 95% passing rate compared to the other literature classes that had an 80% passing rate. Design Based Learning gave her a method for remaining in charge while giving more responsibilities to the students. Grace had three objectives when she began using Design Based Learning: to have students understand the meaning of the themes found in great literature, to motivate students to want to read that literature, and to have students write descriptive compositions using the skills that are outlined in the state required standards. Grace’s students constructed a simulated experience they called Community Building. They role-played the jobs of characters in scenarios about community life in the miniature model of the future. They experienced ensuing conflicts and found solutions together. They made group comparisons and connections to the themes in the literature. In many pieces of literature such as Lord of the Flies, Animal Farm, To Kill a Mockingbird, Romeo and Juliet, and Fahrenheit 451, there is a struggle between the needs and values of individuals versus the community. Her students built Never-Before-Seen learning places to identify an author’s description of how the characters portray what they learn. As they gained insights from examining their own first-hand proposals, they better analyzed the motives of the characters and the deeper meaning of the literature they read. Parallel experiences with their own Community Building and those of fictional characters from their readings led them to identify ways people resolve problems and shape their community. Grace willingly allowed them the building time as she found that the questions and concerns raised by the students’ designs guided their reading, writing, and analysis of the required literature. The students’ work was no less demanding and there were multiple paths to success. Published in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 17, Fall 2004 California Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA 8 Grace compared the final grades of two high school Literature classrooms. The blue at the left indicates a non-DBL classroom, the red indicates her DBL classroom in the same grade level. Conclusion These teachers used the techniques associated with the design professions over and over again in their K-12 classrooms to deliver mandated academic standards. Students set criteria then built physical models to develop and test out their own solutions to the problems they encountered. The lists of criteria for each activity easily turned into a rubric for grading. Using their illustrated solutions, they learned to think critically and to make revisions and modifications by incorporating information from the lessons that pertain to what they were doing. By sneaking up on learning, the students were able to succeed. Teachers like Emily, Teri, Leslie, Don, and Grace find that one small Design Based Learning activity eases their curriculum overload and classroom management issues. They have a concrete method for teaching and evaluating that sticks for the students, and it sticks for the teachers. (This research sample was drawn from the Master’s Degree in Education in Curriculum and Instruction, Design Based Learning started in 1995 at California Polytechnic University, Pomona. It is based on City Building Education’s methodology of Backwards Thinking, started over 30 years ago by Doreen Nelson.) Published in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 17, Fall 2004 California Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA 9