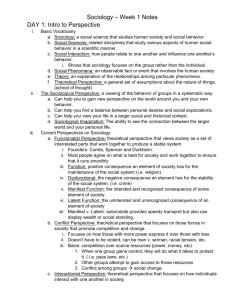

Last Lecture

advertisement

TOWARD A MAP OF SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY As you are developing your theoretical perspectives for your final exam, it is appropriate for us to return to the questions that inspired the development of sociological theory: Who am I? What am I doing here? What should I do next? As I've argued throughout the semester, sociological theory developed in efforts to address these questions. It became institutionalized as an academic discipline (or discourse) when the traditional answers to these questions were challenged by fundamental institutional changes that transformed social relations. As institutions (the family, community, church, economy, and government) changed in the revolutions of the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries, individuals, groups, and organizations sought new answers to these age old questions, thus inspiring the development of a scientific approach to the study of social action (action that takes others into account). There are a variety of different ways in which we might represent the development of sociological theories. The most comprehensive but least elegant approach is intellectual history—a chronology of names and dates with suggestive references to who begat whom. Ritzer offers such a perspective in his maps (see Ritzer, pp. 5, 185-186), which I've attempted to expand with a consideration of politics and social movements (see my map, Figure 1). Figure 1: HISTORICAL AND INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT OF SOCIOLOGY ______________________________________________________________________________ 18th Century Revolutions: Enlightenment, Rights of Persons, Social Contract (Rousseau & Paine) Critique of Philosophy (Kant) Rise of Political Economy (Smith) Dialectics (Hegel) ___________ 19th Century Civil Wars__ Reactionaries (Bonapartists) (Royalists) Economics (Ricardo) Dialectical Materialism (Marx) Socialism (Saint Simon) Social Progress (Comte) Social Evolution (Spencer) Functionalism (Durkheim) Interactionism (Weber) ___________ 20th Century International (World) Wars Simmel Mead Homans Parsons Symbolic Interactionism Blau Merton phenomenology conflict theory NeoMarxism structural historical critical post-structuralism Feminism radical feminism Marxist feminism liberal feminism socialist feminism ______________________________________________________________________________ 2 A more elegant but less comprehensive approach is offered in the appendix of Ritzer— the paradigm approach and the idea that sociology is a multi-paradigm discipline (unlike the hard sciences, each of which is characterized by consensus on the nature of the subject and on the appropriate method of analysis). A third approach, which is yet more elegant but still less comprehensive is what I've called the "philosophical" approach, which distinguishes theories by their underlying assumptions regarding human nature and the nature of existing institutions. In lecture, this philosophical approach has been combined with the historical and with a more formal, structural approach that focuses on the models of social action or social structure (functional/teleological, dialectical, and interactive) that characterize different perspectives. Thus I've presented the development of sociological theory as a series of philosophical/political debates inspired by 18th century revolutions, 19th century civil wars, and 20th century international (or world) wars in which different models of social action or social structure are used to defend or sustain distinctive philosophical or political perspectives (conservative versus radical, liberal, or reactionary). I've offered a dialectical model of theory development in which opposing, contradictory theories clash and become institutionalized as academic disciplines when, first, social institutions are transformed by revolutionary struggles and, second, academic debates are orthogonal to (or independent of) the institutional political debates that divide liberal defenders of the emerging social order from reactionary critics who seek to re-establish traditional institutions. Thus social theory develops in revolutionary situations and becomes institutionalized in the wake of civil wars (if and when the liberals win). In relatively stable political economies social science is coopted by liberals and conservatives. Consequently, theory languishes and applied research 3 flourishes. In this regard theory is revolutionary, not because it inspires revolutions but because it is inspired by revolutions. Quite apart from its utility or comprehensibility as a way of thinking about or mapping sociological theory, this approach is not very effective in encompassing some of the new social theories (phenomenological, post-structural, and radical feminist). We might, however, include these as products of new social movements (anti-Nazi, anti-nuclear, peace, feminist, and environmentalist) that challenge the positivistic (social facts), scientific approach of structural theories and enlarge the philosophical debate to include debates on the nature of reality/knowledge and on the possibility (or desirability) of a value free social science (or, more generally, of a social science, be it value free or not). These theories (and these social movements) are not rooted in revolutionary struggles. They lack a material base and a revolutionary (class) interest. They are, instead, rooted in a philosophical critique of applied science and a humanistic or moralistic critique of the "progressive" vision of social scientists and public policy experts (or planners). They are strong on criticism and weak on alternative vision. Thus we see that contemporary sociological theory is suffering, first, from cooptation by liberals and conservatives and by the lack of an orthogonal (or independent) academic debate. Even if a debate between radicals and reactionaries emerged from the critical-poststructural debate it would not represent contradictory perspectives, since both radicals and reactionaries offer a critique of existing institutions. Furthermore, it would not be orthogonal to the instituted political debate, since the radical-reactionary debate mirrors the liberal-conservative debate, differing only in perspective on the instituted order. 4 Thus the second and more serious problem is the lack of revolutionary struggle within the modern western industrialized nations that support the development of the social sciences. This is a problem that we cannot solve in theory, as the Russian and Chinese experience indicates. Theory does not inspire revolution. Revolution inspires theory. Thus we must muddle though the lack of inspiring theoretical developments and content ourselves with analyses of the failure of social movements that might have had revolutionary potential. After the revolution, we can begin our work anew. Meanwhile, let's consider how we might characterize theoretical perspectives, what our theoretical perspective is, and why we should bother to develop a perspective or to study sociological theory. - Ritzer’s paradigms - social facts - social definition - social behavioral/action - Hogan’s philosophy - image of individual - micro: needs based - gratification seeker - meaning seeker - macro: alienation based - alienated from self/nature - alienated from other/society 5 - image of institutional order - facilitates - individual enterprise - collective enterprise - inhibits - individual enterprise - collective enterprise - bridges from macro to micro theory - functional behaviorist - dialectical interactionist So What? One Last Shot at Education Consider two synthetic, comprehensive (macro/micro) theories of educations. Functional behaviorism combines a micro “gratification-seeker” image of the individual with a macro perspective that views social structure as “impeding” individual (gratification-seeking) behavior and facilitating collective behavior. In this sense, the individual who is not experiencing “anomie” is deferring gratification in deference to the culturally proscribed/prescribed behavior that (s)he learned as a child, which was reinforced in school, and which continues to function as the normative order. From this theoretical vantage point, higher education provides the technical training required for the best and the brightest in order for them to perform the most important and most difficult tasks that society requires. The teacher’s role is to provide a rigorous program of study and examination, with comprehensible procedures and enforceable rules to insure that 6 the best and the brightest will develop their abilities and will be distinguished from their less capable or less ambitious peers. Unequal rewards are necessary, but equal opportunity should be maintained to the extent that is possible within a meritocracy, within which a certain degree of inherited (or ascribed) status is maintained (as a form of cultural lag or latent pattern maintenance). Now consider a different theoretical vantage point. Dialectical interactionism combines a “meaning seeker” micro perspective with an “alienation-based” macro perspective, which views the instituted order as impeding the meaning seeking efforts of the individuals (pursuit of knowledge) as well as impeding collective efforts to meet material (as well as spiritual, emotional, or intellectual) needs. From this vantage point, education is a system imposed on children, which stifles their natural curiosity and attempts to impose “discipline” and “reason” as a counterpart to the “morals” and “values” that they should be learning at home (or in church). The goal of this system is stifle thought (particularly critical thinking) that might interfere with work (producing surplus value for capital). The only way humans can recover their intellectual capacity is through their collective struggle to seize control of the basis for producing and maintaining their material life. Thus the “intelligensia” must follow rather than lead its working class peers. The only defensible value within the academy is the pursuit of critical thinking, which the structure of teaching, research, and service effectively undermines. It is only through the destruction of capitalist enterprise that the productive capacity of labor might be realized. Similarly, it is only through the destruction of the bourgeois university that the intellectual capacity of students might be realized. And, finally, the high priests of the cult of ‘religion and order’ are themselves kicked off their Delphic stools, hauled from their beds in the dead of night, put in prison vans, and thrown into jail or sent into exile. Their temple is leveled to the ground, their mouths are sealed, their pens are smashed, and their law torn to pieces in the name of 7 religion, property, family, and order. Bourgeois fanatics for order are shot down on their balconies by drunken bands of troops, their sacred domesticity is profaned, their houses are bombarded for the fun of it, all in the name of family, religion, and order. (Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, p. 156, in David Fernbach (Ed.) Surveys From Exile, Political Writings Volume II (Vintage [Random House], 1974). Might you think about your job differently if you were a college professor who subscribed to this dialectical interactionist (rather than the functional behaviorist) theoretical approach? So why would you want to discover your theoretical orientation? - to better understand your life: I feel alienated and depressed at the end of the semester, but at least I know why. - to enlighten/corrupt the minds of others - to change the world (maybe you should leave the academy and get a job in a factory) 8