SCRIPPS COASTAL RESERVE—MANAGEMENT PLAN

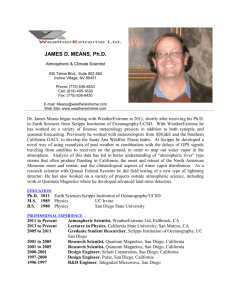

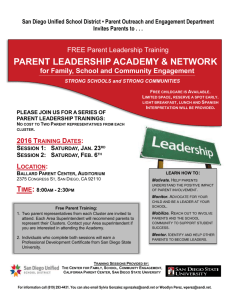

advertisement