Grammatical and lexical Features of Scientific and Technical

advertisement

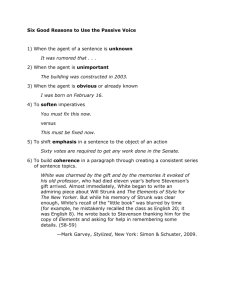

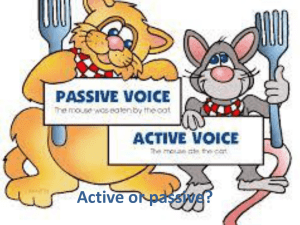

Mohammad Al Towaim MA Applied Linguistics Grammatical and Lexical Features of Scientific and Technical Language Contents Introduction 1 Section 1: Scientific/Technical Language 2 Section 2: Some of the Grammatical and Lexical Features of Scientific and Technical Language 3 2.1 Noun compound 2.1.1 Examples of given extract 2.2 The use of the passive 2.2.1 Examples of given extract 2.3 Nominalisation 2.3.1 Examples of given extract Section 3: Lexical features of scientific/technical language 3.1 Semi-technical vocabulary 3.1.1 Examples of given extract Section 4: Some Implications for Teaching Grammar and Vocabulary in 3 4 4 7 8 8 9 10 10 11 ESP Conclusion 13 References 14 Appendix 16 Introduction Many scholars and researchers have discussed the idea that scientific writings differ from everyday writing both in grammatical and lexical features. This paper will consider this issue and try to clarify the differences between these writings. In section one, we will briefly look into some of literature review about this topic. Then we will discuss the grammatical and lexical features of the scientific writings, as we will refer to the given text (see Appendix) and point out its scientific or technical register, starting with the grammatical features and its distinguishing style that might differ from general English. Afterwards, we will clarify the lexical features of scientific writings. In section four, we will discuss some pedagogical implications for teaching grammar and vocabulary in ESP. In the conclusion I will sum up what has been said in this paper and refer to the importance of corpora in ESP. 1 Section 1: The scientific/technical language Is the language of scientific and technical text different from general language? In order to answer this question, we should look at scientific/technical language to know to what extent it is distinguished from general language. A text is counted as 'scientific English' when there are generally considerable differences between any particular genres, especially, according to Parkinson (2000), in vocabulary, grammar and discourse structures. If we focus on scientific language, it can be said, according to Hutchinson & Waters (1987), that there are important differences between scientific/technical language and general language, in vocabulary and the higher frequently of some grammatical styles. So, to sum up the answer, it can be declared that there are important distinctions between scientific and general language. Halliday (1993), cited in Parkinson (2000), point out that a text is considered as 'scientific' because of the special features relating together throughout the text. These features will be considered in section 2 2 Section 2: Some of The grammatical and lexical features of scientific and technical language In this section, I am going to focus on some features of scientific/technical language, which are noun compound, use of passive and nominalisation. Each features will be concluded with references to the given extract (see Appendix). 2.1 Noun compound: A noun involves two or more nouns relating together as a new concept. In general, there is a chain of nouns where some nouns modify the head noun (Ferguson (2004:1). Modifying noun Head noun nuclear submarine refit centre beginner level francophone ESL learners A noun compound, as Master (2003) indicates, is common in scientific writing. It is important, Ferguson (2004) says, because its function is as a means to represent information in a compact and dense form. The noun compound has many other functions making it suitable for scientific writing. Ferguson (2004:1) has illustrated some of them as follows: i. Noun compounds are sometimes used as technical terms. They can be used in this sense for the first mention/introduction of a technical concept. ii. Equally commonly, noun compounds may be used for the 2nd and 3rd mentions of a cluster of concepts. Very often the noun compound is the final stage in the compression of a set of concept. Thus, when the idea/concept is introduced for the first time, it may be mentioned in a full form. When the concept/idea is mentioned again, it may be more economical for the writer to refer to its 3 compressed form: i.e. as a noun compound. This process is illustrated in the example below: e.g. The study of how quickly cracks in the glass grow has made significant progress recently. → Glass crack growth rate was found to be related to ….. iii. One advantage for the writer of a noun compound is that they are more easily shifted within the clause than their corresponding fuller form. Thus, noun compounds are useful for presenting given information at the beginning of the sentence in subject or theme position. It is also customary to present given information in as short and compressed a form as possible, and this a noun compound allows in the example above. In fact, the usage of noun compounds involves some difficulty. Master (2003) points out that it is not easy to understand the noun compound, even if readers can decode the individual words. 2.1.2 Examples of given extract: (see Appendix): - We report a double blind… - …crossover trial of an angiostensin converting enzyme inhibitor… 2.2 The use of the passive: It has been commonly accepted that the one of the most frequent grammatical features of scientific/technical writing is the use of the passive. For instance, Royds-Irmak (1975:7) cited in Master (1991:16) declares that "In science, a sentence is often written in a passive form because the important idea is not who did something, but what was done ". Moreover, Quirk et al. (1972:808), cited in Master (1991:16), states that: The passive has been found to be as much as ten times more frequent in one text than in another. The major stylistic factor determining its frequency seems to be related to the distinction between informative and imaginative 4 prose rather than to a difference of subject matter or of spoken and written English. The passive is generally more commonly used in formative than in imaginative writing, notably in the objective, impersonal style of scientific articles and news items. On the other hand, Blicq (1981:319), cited in Master (1991:16), says "… unfortunately, many scientists and engineers in industry still believe that everything should be written in the passive voice… with the passage of time, this outdated belief is slowly being eroded". Furthermore, Eisenberg (1982:151) cited in Master (1991:16) points out that "… the use of the passive verb slows down the pace, requires more words, and tends to make the going difficult for your readers." In fact, all the remarks mentioned above are, according to Ferguson (2006), unable to illustrate why, and in which situations, the passive is to be preferred over the active, and vice-versa. However, the table below, Master (1991:22), shows that the passive voice has a greater use in scientific writing, but the active still has dominance. Comparison of Active/Passive Ratios (in Percents) in Several Studies Author Text Mid-brow Barber (1962) Textbook 72/28 Rumszewicz (?) Scientific text 72/26 White (1974) General textbooks 75/25 Laboratory report 37/63 Scientific textbook Wingard (1981) 78/22 Medical journal 65/35 Medical text Tranoe (1981) High-brow 76/24 Astrophysics journal 89/12 Astrophysics journal 81/19 5 One of the researches examining the actual use of the passive is a study, mentioned in the table above, produced by Tarone et al. (1981). This study has used corpus to analysis two astrophysics journal papers. The result “…shows that the active voice is used much more frequently than the passive and, more importantly, that the active first person plural we verb form seems to be regularly used at strategic[points]..” Tranoe et al (1981:201). This result appears in the table below: Overall frequently of active and passive verbs in the Stoeger and Lightman papers Stoeger Lightman Total number of verbs 244 370 Active verbs 217 (88.5%) 301 (81.4%) Active we verbs 58 (23%) 40 (10.8%) Passive verbs 27 (11.5%) 69 (18.6%) Total verbs, existential 137 248 Active verbs 110 (80%) 179 (72.2%) Active ‘we’ verbs 52 (37%) 40 (16.1%) Passive verbs 27 (20%) 69 (27.8%) omitted. Tranoe et al. (1981:194) Moreover, the corpus suggests the following generalizations: i. Writers of astrophysics journal papers have a tendency to use the active weform voice to show points in the logical development of the argument where they have made a distinctive procedural choice; the passive voice is used when the writers are following established or standard procedures. ii. When a comparison is being made between a writer’s work and that of other researchers, writers use the active voice for their own work and the passive voice for the research that is being contrasted. 6 iii. When the writers just cite other researchers’ work, they use the active form of the verb. iv. When writers refer to their future work, they use the passive verb. v. The usage of the passive or active voice in these papers is conditioned by the ‘discoursal functions of focus’ or by the length of certain sentence elements. Tranoe et al. (1981:201) conclude these generalizations by saying: "it should be noticed that we only claim that these generalizations hold for professional journals". As the tables above indicate, both the active and passive are used in scientific/technical writing. Thus, we could conclude the debate by saying that the choice of either active or passive voice is dependent on the function that the writer prefers Dudey-Evans & John (1998:76) state that: “The idea that scientific…writing uses the passive voice more frequently than the active is a myth; what is true is that such writing uses the passive voice more frequently than some other types of writing….The choice of active or passive is constrained by functional considerations...” 2.2.2 Examples of given extract: (see Appendix) i. Active voice: - We report a double blind… - We used a crossover study and carried out… ii. Passive voice: - Each patient was given either enalapril or placebo… - …in which treatment given was randomised… - Randomisation was carried out… 7 2.3 Nominalisation: Nominalisation is a word derived from a verb or an adjective (e.g. applicability from applicable). It is usually ended by suffixes such as –ation, -ity, or -ment. Nominalisation, according to Dudey-Evans & John (1998) is a kind of abstract or economical language. Thus, as we will see in the given extract (see Appendix), nominalisation is used to make the phrases more simple. Dudey-Evans & John (1998:78) cited the text below indicating that nominalisation "…enables complex information to be packaged into a phrase that is simple from a grammatical point of view and that can be picked up in the theme of the following sentence : "A high primary productivity is almost invariably related to a high crop yield. High productivity can be achieved by ensuring that all the light which falls on the field is intercepted by the leaves…. Greater efficiency in photosynthesis could perhaps be achieved by selecting against photorespiration". Adapted from Dudey-Evans & John (1998:78) 2.3.2 Example of given extract: (see Appendix) - Randomisation was carried out by the suppliers of the drug. 8 Section 3: Lexical features of scientific/technical language Notion (2001:198) has divided technical vocabulary into four categories, ordered from the most technical in category 1 to the least in category 4: i. Category 1: The vocabularies are restricted to the following fields. Law: jactitation, per curiam, closture Applied Linguistics: morpheme, hapax legomena, lemma Electronics: anode, impedance, galvanometer, dielectric Computing: wysiwyg, rom, pixel ii. Category 2: The vocabulary can be found in different fields, but with different meanings. Law: cite (to appear), caution (vb) Applied Linguistics: sense, reference, type, token Electronics: induced, flux, terminal, earth iii. Category 3: The vocabulary is found in and outside this field, but the majority of its uses with a particular meaning are in this field. Law: accused, offer, reconstruction (of a crime) Applied Linguistics: range, frequency Electronics: coil, energy, positive, gate, resistance Computing: memory, drag, window iv. Category 4: the vocabulary is more common in this field, but there is little or even no specialisation of meaning. However, a learner with knowledge of the field will know the meaning better. Law: judge, mortgage, trespass Applied Linguistics: word, meaning Electronics: drain, filament, load, plate Computing: print, program, icon 9 It is obvious from the categories above that there is a degree of 'technicalness" in which, as Notion (2001) states, this degree is governed by a word's restriction to a specific field. Thus, category 1 involves clearly technical words, since they are exclusive to a specific area in both form and meaning. In contrast, words in category 4 are capable of being used in more than one field, and, therefore, can be considered as less technical. 3.1 Semi-technical vocabulary: There are some words which could be related to all specialised disciplines. Such words, according to Dudely-Evans & John (1998), are counted as semi-technical words. We will see examples of it below. 3.1 Example of given extract: (see Appendix) i. Technical lexis: - ...crossover trail of an angiotensin... - Each patient was given either enalapril or placebo… - ...fluid overload receiving dialysis... ii. Semi-technical vocabulary: - ... an angiotensin converting enzyme... -... patients with chronic fluid... -...of the ethics committee of this hospital... 10 Section 4: Some Implications for Teaching Grammar and Vocabulary in ESP In the light of sections 2 and 3, we could answer the question raised at the beginning: Is the language of scientific and technical text different from general language? The short answer is Yes. We have seen that scientific/technical language is different from general language. Therefore, it is worth focusing on the grammatical and lexical features of a area being considered, in order to improve the methods of ESP and its implications, following the statement by Ewer & Davies (1988) that the work done to identify the features of scientific language and its differences with general language has a positive impact. In this section, we will attempt to point out the role of grammar and vocabulary in the context of teaching ESP, and to indicate some implications for teaching grammar and lexis in ESP. It has been claimed that ESP teaching is not concerned with grammar. However, Dudley-Evans & John (1998) declare that grammar teaching is one of the ESP teacher’s duties. Students who have grammatical difficulties will face a lot of troubles in language skills. Work on grammar, according to Dudley-Evans & John (1998), is supposed to integrate with the teaching of language use. Regarding vocabulary, some scholars (see Dudley-Evans & John (1998), and Notion (2001)), and claim that it is not the English teachers' job to teach technical words. However, there is some circumstance where teachers should pay an effort to help their students in understanding the technical vocabulary. For example, Dudley-Evans & John (1998:81) declare that "…students usually need to be able to understand the technical vocabulary in order to do the exercise". Thus, "… it may be also the duty of the ESP teacher to check that learners have understood technical vocabulary appearing as carrier content for an exercise". Moreover, Notion (2001:204) has determined that "considering the large number of technical words that occur in specialized texts, language teachers need to prepare learners to deal with them. Furthermore, Notion (2001:205) states that: 11 "The main purpose in isolating an academic or technical vocabulary is to provide a sound basis for planning teaching and learning. By focusing attention on items that have been shown to be frequent..” In terms of language courses, Parkinson (2000) states that in teaching language through content, students are not only learning the language, but they are using the language to learn. Therefore, Parkinson (2000:374) has suggested a theme-based language course for science students, in which learners “…must be embedded in a real topic and any reference to grammar or strategies for working out the meaning of new vocabulary etc. is subsidiary to this major topic.” The purpose of this is: to make the materials authentic, involving, as far as possible, real scientific activity; to make them relevant and interesting in themselves. Grammar exercises, for example, if done for their own sake, are usually boring whatever the topic; most importantly, the purpose is to make material capable for teaching appropriate genres i.e. capable of providing the students with schemata in terms of form as well as content, in addition to teaching grammar, vocabulary and coherence etc. One of the most significant implications is the use of corpora in the ESP field, especially when the teachers and researchers have established their own corpora to help them in specific aims. This kind of small corpus has a positive impact on grammar and vocabulary teaching in ESP context, in a way which is more suitable than a large corpus. Partington (1998) cites Flowerdew's example (1993), which is a collection adapted from Biology lecture texts, used for teaching English for undergraduate students attending classes in this particular area of science. 12 Conclusion In this paper I have considered the grammatical and lexical features of scientific writing that will help both the learners and teachers of ESP in understanding the differences between scientific writing and general writing. I have clarified the grammatical and lexical features of scientific writing. In each feature, I have referred to the examples adapted from the given text. Also I have stated some pedagogical implications that would be useful in teaching ESP. In conclusion, studying the features of scientific writings will enable us to understand and therefore develop ESP courses that would be useful. Furthermore, developing special corpuses for each scientific field will make it easier both the teachers and learners of ESP. From all this, I would like to point out the importance and significance of corpora in ESP. 13 Reference Dudley-Evans, T. and St John, M. 1998. Developments in English for Specific Purposes: A multi-disciplinary approach. CUP. Ewer, J. and Hughes-Davies 1987. Further Notes on Developing an English Programme for Students of Science and Technology' In Swales, J.(ed). Episode in ESP. Prentice Hall. p.45. Ferguson, G. 2004. Handout: 'Lecture on The Grammar in ESP: Noun Compound' University of Sheffield. Ferguson, G. 2006. Handout: 'Lecture on in The Grammar in ESP: The Use of The Passive in Scientific and Technical Writing' . University of Sheffield. Hutchinson, T. and Waters, A. 1987.. ‘ESP at the Crossroads’. In Swales, J.(ed). Episode in ESP. Prentice Hall. p.174. Master, P. 1991. Active verbs with inanimate subjects in scientific pros. English for specific purposes. 10, 15-33. Master, P. 2003. Noun Compounds and Compressed Definitions. Volume 41, Issue 3. Available on line: http://exchanges.state.gov/forum/vols/vol41/no3/p02.pdf Nation, I. 2001. Learning Vocabulary in Another Language. Cambridge: CUP. Parkinson, J. 2000. Acquiring scientific literacy through content and genre: a theme-based language course for science students. English for Specific Purposes. 19 369-387 Partington, A. 1998. Patterns and meaning. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Tarone, E., Dwyer, S., Gillette, S., Icke, V. 1987. On the use of the passive in two astrophysics papers. In Swales, J. (ed.). Episode in ESP. Prentice Hall. p.188. Wood, A. 2001. International Scientific English: The language of research scientists around the world. In Flowerdew, J. and Peacock, M. 2001. Research Perspective on English for Academic Purposes. Cambridge University Press. p71 14 Appendix: The given text: We report a double blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of an angiostensin converting enzyme inhibitor, enalapril, in patients with chronic fluid overload receiving dialysis. […] We used a crossover study and carried out procedure within the study according to the standards of the ethics committee of this hospital. Each patient was given either enalapril or a placebo in the first period of the treatment. What was given was randomised, with 13 patients receiving enalapril first and 12 the placebo first. Randomisation was carried out by the suppliers of the drug. 15