Chapter 5 Large Biological Molecules

advertisement

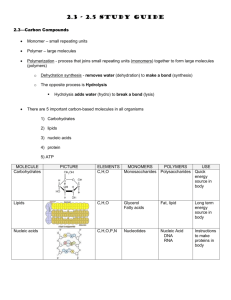

Chapter 5. THE STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF MACROMOLECULES. Summary of Chapter 5, BIOLOGY, 10TH ED Campbell, by J.B. Reece et al. 2014. Small molecules have unique properties arising from the orderly arrangement of its atoms. The major groups of biologically important molecules are carbohydrates, lipids, proteins and nucleic acids. Usually they are very large containing thousands of atoms: macromolecules. Macromolecules are giant molecules formed by the union (bonding) of smaller molecules. They consist of hundreds of thousands of atoms. This is another level of biological organization. I. MACROMOLECULAES ARE POLYMERS Most macromolecules are polymers. These are long chains formed by linking small organic molecules called monomers. Poly: many; Meros: parts 1. Synthesis and Breakdown of Polymers Polymerization is the linking together of monomers to form polymers. It takes place through dehydration reactions. 1. Condensation is the chemical process by which monomers are linked together. A molecule of water is removed: dehydration synthesis. Each of the two monomers forming the bond contributes one part of the water molecule, the hydroxyl group [–OH] and the hydrogen [–H]. 2. Hydrolysis is the chemical process by which polymers can be degraded into monomers. A molecule of water is broken into H and OH and added to the broken bonds. Each molecular product receives a hydroxyl group or a hydrogen. Hydrolysis is the reverse of condensation (dehydration synthesis). These processes are facilitated by enzymes. 2. Diversity of Polymers A infinite number of polymers can be built from a limited number of monomers. Each class of polymer (e. g. lipids, proteins, etc.) is formed from a specific set of monomers. Proteins (polymer) are made of thousands of amino acid units (monomer). The uniqueness of organisms depends on the unique arrangement of the same monomers. Macromolecules are constructed from only 40 to 50 common monomers and some others that occur rarely. II. CARBOHYDRATES Carbohydrates include sugars and their polymers. 1. Sugars Carbohydrates contain carbon hydrogen and oxygen in a ratio of 1:2:1 or [CH2O]n. Monosaccharides are simple sugars. They serve as sources of energy and carbon atoms. Normally containing 3 to 7 carbon atoms. A hydroxyl group is bonded to each carbon except one. That carbon is double bonded to an oxygen atom forming a carbonyl group; depending on the position of the carbonyl group, the sugar is an aldehyde (aldose sugars) or a ketone (ketose sugars). Glucose is an aldose, the carbonyl group is at the end of the carbon skeleton. and fructose a ketose, the carbonyl group is within the carbon skeleton. See Fig. 5.3. Most sugar names end in -ose. In aqueous solutions, 5- and 6-carbon molecules form rings. They are not linear. See Fig.5.4. Dissaccharides are made of two monosaccharide units. Two monosaccharide rings joined by a glycosidic linkage, a covalent bond formed between two monosaccharides by a dehydration reactions. They can be split by the addition of water, hydrolyzed. Maltose is formed by linking two glucose monomers and sucrose by linking one glucose and one fructose. Glucose linked to galactose produces lactose, the sugar in milk. See Fig. 5.5. 2. Polysaccharides. Repeating chains of monosaccharides. Single long chain or branched chain. They function either as energy storage material or as building blocks of cellular structures. a) Storage polysaccharides: Plants and animals store carbohydrates for later use. Some important polysaccharides: Starch is made entirely of glucose and is the main storage carbohydrate of plants: 1-4 linkages; this arrangement makes the starch molecule helical. Amylose is the simplest form of starch; it is unbranched and helical. Amylopectin is a branched form with 1-6 linkages at the branch point. Source: http://www.lsbu.ac.uk/water/hysta.html Glycogen is made of glucose and is the storage carbohydrate of animals: 1-4 linkages. The glycogen molecule contains more branches than the amylopectin molecules. It is stored mostly in the liver and muscles. b) Structural polysaccharides Polysaccharides used as building material, e.g. cellulose is used to build the cell wall of plant cells. Cellulose is also made of glucose monomers and is a structural carbohydrate: 1-4 linkages. The angles of the bonds of the 1-4 linkages make every other glucose monomer "upside down." Cellulose molecules are straight and never branched. Its hydroxyl groups are free to form hydrogen bonds with those of adjacent molecules. In plant cell walls, cellulose molecules form minute cables called microfibrils. Enzymes that digest starch by hydrolyzing its linkages cannot hydrolyze the linkages of cellulose. Very few organisms can digest cellulose. In most cases cellulose passes through the digestive tract and is eliminated in the feces. Chitin is a polysaccharide used by arthropods in building the exoskeleton. The chitin monomer is a glucose-like molecule called N-acetylglucosamine in which an OH group is replaced by a chain of R–NHCOCH3 group. When it becomes encrusted with calcium carbonate, it becomes hard. Chitin is also found in the cell wall of fungi, insects, spiders, crustaceans and other animals. Some modified and complex carbohydrates have special roles: Galactosamine is a structural carbohydrate present in cartilage; it is amino derivative of galactose, an enantiomer of glucose. Glycoproteins and glycolipids are commonly found on the outer surface of cells. These are proteins with polysaccharide or fatty acid branches attached. III. LIPIDS Lipids are diverse group of compounds made mostly of carbon and hydrogen, with a few oxygen atoms found mainly in functional groups. Hydrophobic molecules: water repellent. They are made mostly of hydrocarbons. Soluble in nonpolar solvents. For energy storage, hormones, structure of cell membrane. Neutral fats, phospholipids, steroids, waxes, carotenoids and other pigments. 1. Fats Fats are storage lipids Fats are large molecules made from smaller molecules linked together by dehydration reactions. Neutral fats are made of glycerol and three fatty acids. Glycerol is a 3-carbon alcohol. Fatty acids are long unbranched hydrocarbon chain with a carboxyl group (COOH) at one end. The carbon skeleton of the fatty acid usually has 16 to 18 carbon atoms. At one end there is a carboxyl group that gives these molecules the name of fatty acids. The nonpolar C–H is the reason for the hydrophobic properties of the hydrocarbons. When a fatty acid combines with a glycerol molecule a molecule of water is removed and an ester linkage is formed. The fatty acids in a fat molecule may or may not be the same. Triglyceride (triacylglycerol) is a synonym for fat. Saturated fats have a maximum number of hydrogen atoms in the chain, and are usually are solid at room temperature, e. g. lard, blubber and butter. Unsaturated fats have double bonds between some of the carbon atoms and have less than the maximum number of hydrogen atoms. Unsaturated fats have bends in the chains that prevent the aligning with the adjacent chain and prevent the van der Waals forces from acting. They are usually liquid at room temperature, e. g. vegetable oils. Fats store at least twice as much energy as starch. Humans and mammals store their fat in the adipose tissue of the body. This tissue serves as a reservoir of energy, as an insulator, and cushions internal organs. 2. Phospholipids Phospholipids are structural lipids Phospholipids are major components of cell membranes. Phospholipids differ from fats in having only two fatty acids instead of three and a phosphate group with a small additional molecule attached to the third carbon of glycerol instead of a hydroxyl group. The hydrocarbon chains are hydrophobic but the phosphate group and its attached organic molecule (e. g. choline, lecithin) are hydrophilic (affinity for water). Amphipathic molecule. Phospholipids form micelles and bilayers or double layers in aqueous solutions. A micelle is a droplet formed by phospholipid molecules arranged with their hydrophilic heads facing out toward the water medium, and their hydrophobic tails facing inward away from the water. Bilayers are double membranes. In a bilayer, the heads face toward the aqueous solution and the tails point to the interior of the membrane. 3. Steroids Steroids can be part of cell membrane structure, e.g. cholesterol, or act as signal molecules that trigger responses in specific tissues, e.g. hormones are steroids. Steroids are made of four fused rings. Steroids vary in the chemical groups attached to the rings. Cholesterol is a steroid component of cell membranes of animals. Steroids have their carbon skeleton bent into four fused rings with a carbon chain attached to one of the rings. Three rings have six carbon atoms and one has five carbons. There are different functional groups attached to the rings. The length and structure of the chain distinguishes one steroid from another. “All steroids have the same fundamental structure of four (tetracyclic) carbon rings called the steroid backbone or steroid nucleus. The addition of different chemical groups at different places on this backbone leads to the formation of many different steroidal compounds, including the sex hormones progesterone and testosterone, the anti-inflammatory steroid cortisone, and the cardiac steroids digoxin and digitoxin.” http://waynesword.palomar.edu/plsept96.htm#foam Some steroids function as hormones (e. g. sex hormones), chemical messengers in the body of animals. The function of steroids depends on the functional groups attached to their carbon rings. Cholesterol is a structural component of cell membranes but it is also a precursor from which other steroids are made. Carotenoids are plant pigments involved in photosynthesis. They are insoluble in water. 4. Other lipids Waxes are complex lipids made of many fatty acids linked to a long-chain alcohol. Hydrophobic Coating of fruits and leaves, beeswax, ear wax, some insects. The following is the simplified structural formula of bees wax. http://www.cyberlipid.org/wax/wax0001.htm#2 IV. PROTEINS Proteins make more than 50% of the dry weight of most cells. Proteins perform a variety of functions in the body: structural support, transport of other molecules, body defense, signaling between cells, chemical catalysts called enzymes, storage, and other functions. See fig. 5.13, page 76. Proteins vary in their structure so they can perform specific functions. Proteins are large complex molecules, polymers of amino acids, joined by peptide bonds. These polymers are called polypeptides. 1. Amino Acid Monomers. A protein is made one or more polypeptides folded and coiled into a specific conformation. 20 amino acids (AA) involved. See fig. 5.14, page 77. Carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and usually sulfur. AA contain an amino group, NH2, at one end and a carboxyl group, COOH, at the other end, both attached to an alpha carbon (α). AAs have a variable side chain (R group) that determines the specific physical and chemical properties of each AA. Except for glycine all other 19 amino acids used to synthesize proteins can exist as L- or D- enantiomorphs. Only L- amino acids are used for protein synthesis. Bacteria and plants can synthesize all AA. There are a few exceptions. Animals synthesize some but not all AA. Essential AA must be obtained from the diet. Summarizing the four components of an amino acid: alpha carbon, amino group, carboxyl group and the side chain. AAs are usually ionized in the cell. See Figure 5.14 on page 77 of your textbook. The properties of the AA depend on the side chain. Non-polar side chain made of hydrocarbons makes the AA hydrophobic. Polar contain O, S or N on the side chain making the AAs hydrophilic. Negative side chain makes the AA acidic. This is due to the presence of a carboxyl group in the side chain that is usually dissociated at the cellular pH. Positive side chain makes the AA basic; the side chains contain amino groups. Both acidic and basic side chains are hydrophilic. More: http://users.rcn.com/jkimball.ma.ultranet/BiologyPages/E/Enantiomers.html 3. Polypeptides The peptide bond is formed by a dehydration reaction. Two AA combine to form a dipeptide; three form a tripeptide; many form a polypeptide. The amino end of one AA joins the carboxyl end of the adjacent AA. An enzyme catalyzes the dehydration reaction. The resulting covalent bond is called a peptide bond. See fig. 5.15, page 78. When this process is repeated thousands of times the resulting molecule is called a polypeptide. Polypeptide chain may contain thousands of AA. 4. Protein Structure and Function. Polypeptide and protein are not synonymous. Proteins consist of one or more polypeptide chains twisted into a unique shape. Some proteins are roughly spherical (globular proteins) or elongated like a fiber (fibrous proteins). The function of the protein depends on its ability to bind to another molecule. The fit between the two molecules is usually very specific. 5. Four Levels of Protein Structure Proteins have four levels of organization. See fig. 5.18, pages 80 and 81. Primary structure: a unique sequence of AA for each polypeptide chain. The sequence of AA is determined by inherited genetic information. All proteins of a kind have the same AA sequence, e. g. all lysozyme molecules. A change in the sequence of AA is called a mutation. Secondary structure results from hydrogen bonds between H and O atoms of the backbone of the chain resulting in coiling (α helix) or folding (β pleated sheet). The side chains atoms are not involved in the secondary structure of polypeptides. Tertiary structure is the overall shape of the polypeptide due to the interaction among the side chains, R groups. Hydrophobic interactions between side chains usually end up in the interior of the twisted polypeptide chain while hydrophilic side chains are exposed to the aqueous solutions. Disulfide bridges are formed between the two sulfhydril groups of the AA cysteine. This is a strong bond. Van der Waals forces, ionic bonds and hydrogen bonds also contribute to the tertiary structure of the polypeptide chain. Quaternary structure is the relationship among several polypeptide chains of a protein. These polypeptide chains become aggregated into a functional protein. Fibrous proteins have several polypeptides coiled or aligned into rope-like structures. Globular proteins are roughly spherical or compact. 6. What Determines the Protein Structure. The shape of the proteins determines its function. See animation: http://www.stolaf.edu/people/giannini/flashanimat/proteins/protein%20structure.swf Protein conformation depends also on the physical and chemical conditions of the environment like salt concentration, temperature, pH, etc. Changes in any of these conditions can cause the protein to unravel and become denatured. Proteins become denatured become biologically inactive. Scientists do not know little about the principles of protein folding. Most proteins probably go through several intermediate stages before achieving its active conformation. 7. Protein Folding in the Cell Chaperonins or chaperone proteins help in the proper folding of proteins but do not specify the conformation. They protect the polypeptide from denaturing influences in the cytoplasm. X-ray crystallography is a method used in determining the three dimensional structure of a protein. Misfolding of polypeptides is a serious problem in cells. Many diseases such as cystic fibrosis, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and mad cow disease are associated with the accumulation of misfolded proteins. V. NUCLEIC ACIDS SOTRE, TRANSMIT, AND HELP EXPRESS HEREDITARY INFORMATION. Encoded in the structure of DNA is the information that programs all the cell's activities. The DNA molecule contains hundreds of thousands of genes. Genes determine the polymer sequence of AA in a protein. 1. The Roles of Nucleic Acids. Proteins are needed to implement what is in the genetic code, in the DNA. Two classes: DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and RNA (ribonucleic acid). Transmit hereditary information. Determine what the cells manufacture. Nucleic acids are polymers that serve blueprints of proteins. DNA is the genetic material that organisms inherit from their parents. Flow of genetic information within the cell. See Fig. 5. 23. DNA → mRNA → protein DNA is located in the nucleus of the cell. Protein synthesis takes place in organelles called ribosomes found in the cytoplasm of the cell. Messenger RNA, mRNA, is synthesized in the nucleus following the DNA blueprint and then moves to the ribosomes with the message of about the protein to be synthesized. 2. Structure of nucleic acids. Nucleic acids are polymers of nucleotides. They are called polynucleotides. A nucleotide is made of three parts: an organic molecule called a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar (5-C sugar), and a phosphate group. There are two groups of nitrogenous bases: See fig. 5.24, page 85. Pyrimidines: 6 member ring of carbon and nitrogen atoms. Nitrogen atoms tend to take H+ from water and from there the name "nitrogenous base" is derived. Cytosine (C), thymine (T) and uracil (U). Cytosine is found in both DNA and RNA; thymine is found only in DNA; uracil found only in RNA. Purines: Made of a six-member ring fused to a five-member ring. Nitrogen and carbon make the rings. Adenine (A) and guanine (G). Both are found in DNA and RNA Pentose sugars: Ribose is found in RNA and deoxyribose in DNA. They differ in the absence of an oxygen atom on the 2-carbon of deoxyribose molecules. Deoxy- = without an oxygen. The combination of a sugar with a nitrogenous base forms a nucleoside (with an S and not a T.) The addition of a phosphate group to a nucleoside makes a nucleotide also known as a nucleoside monophosphate. 3. Nucleotide polymer The linkage of nucleotides into a polynucleotide involves a dehydration reaction. Nucleotides form polymers with the formation of a covalent bond between the phosphate on one nucleotide and the sugar of the next: the sugar-phosphate backbone. These covalent bond are of a kind called phosphodiester bond. 4. The Structure of the DNA and RNA molecule. The resulting polymer forms the backbone that will make the DNA or RNA molecule. The nitrogenous bases stick out to the side of the backbone. The pentose (sugar) in RNA is ribose, and in DNA is deoxyribose. The carbons in these sugars are numbered and a prime (’) is placed after them, e.g. the second carbon is written as 2’, two prime. The carbon that stick up from the ring is the 5’ carbon. The phosphodiester linkages occur between the –OH group on the 3’ carbon of one nucleotide and the phosphate on the 5’ of the next. The two free ends of the backbone chain are different from each other. One end has a phosphate attached to a 5’ carbon and the other has a hydroxyl attached to 3’ carbon. We refer to these as the 5’ and the 3’ ends of the strand. DNA molecule have two polynucleotides or strands that wind around and imaginary axis. The DNA molecule is made of two polynucleotide chains or strands forming a double helix. The two sugar-phosphate backbones run in opposite 5’→3’ directions from each other, an arrangement referred to as antiparallel. 5’-ATGGCAACC-3’ 3’-TACCGTTGG-5’ The strands are held together by hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces established between facing nitrogenous bases. Only certain bases are compatible to establish the required hydrogen bonds. In other words, the two strands of a double helix are complementary: Adenine always pairs with thymine, a purine with a pyrimidine. Guanine always pairs with cytosine. If a strands has the sequence ATGGCAACC, its complementary strand will be TACCGTTGG. The complementarity of the strands makes it possible to make an accurate copy of each of the two strands and, therefore, of the genes. The linear sequence of bases is passed from parents to offspring. Closely related individuals have greater similarity in their DNA and proteins than unrelated individuals. Closely related species will share a greater portion of their DNA than distantly related species. The sequence of nucleotides in these polymers is limitless and so is the number of nitrogenous bases forming the side branches. Genes are made of hundreds of nucleotides. RNA molecules exist as single strands. Complementary base pairing can occur between two RNA strands or between two regions of the same strand. Uracil replaces thymine in RNA. There is no thymine in RNA 6. Proteonics and Genomics Genomics refers to the analysis of large sets of genes or whole genomes. Proteonics is the analysis of large set of proteins. This is done with the use of software and computers, bioinformatics. Similar DNA indicates close evolutionary relationship. Summary. 1. Macromolecules of life: carbohydrates, lipids, proteins and nucleic acids Polymers and polymerization Monomers Dehydration reactions Condensation reactions Hydrolysis 2. Carbohydrates Structure - carbon hydrogen and oxygen in a ratio of 1:2:1 or [CH2O]n. Include sugars and polymers of sugars Monosaccharides – aldoses and ketoses; ring form in aqueous solutions. Polysaccharides – glycosidic linkage Storage polysaccharides – starch (amylose, amylopectin) and glycogen Structural polysaccharides – cellulose and chitin 3. Lipids Structure - carbon and hydrogen, with a few oxygen atoms found mainly in functional groups. Hydrophobic Fat structure: glycerol, ester linkage, fatty acids Fatty acid structure – hydrocarbon, carboxyl group; saturated, unsaturated Phospholipids – hydrophilic head, hydrophobic tail Steroids – skeleton of four fused rings 4. Proteins Structure – polymer of amino acids Peptide bond – learn the structure of the peptide bond and how it is formed Polypeptides Conformation determines how it words - enzymes Four levels of protein structure o Primary: unique sequence of AA o Secondary: repeated portions of coils and folds; alpha helix, pleated sheets o Tertiary: formed by the interactions of side chains of the AA that causes three dimensional structures; ionic and H bonds, disulfide bridges, van der Waals interactions. o Quaternary: overall structure of the protein due to the aggregation of several polypeptide subunits. Folding and denaturing of proteins 5. Nucleic Acids DNA and RNA Polymers of monomers called nucleotides Nucleotides structure: sugar, phosphate and nitrogenous base Two sugars: ribose and deoxyribose Four nitrogenous bases: o Purines have two rings: adenine and guanine o Pyrimidines have one ring: cytosine and thymine (or uracil in RNA) DNA double helix Base pairing: C – G and A - T 6. Genomics and Proteonics. Bioinformatics