How Objectivity Matters

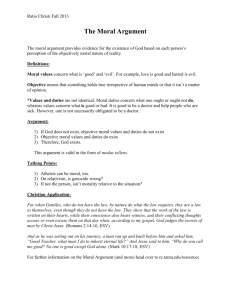

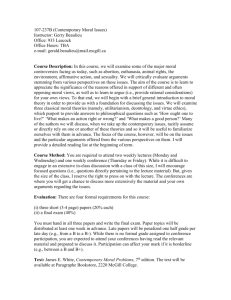

advertisement