84 page - Home - KSU Faculty Member websites

advertisement

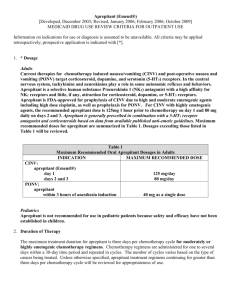

84 Notes APREPITANT: A PROMISING ANTIEMETIC FOR PREVENTION OF CHEMOTHERAPY-INDUCED NAUSEA AND VOMITING Mohammed A. Aseeri يالحظ ثيرظم ظل رضىماظذ رضظتيل ي عالظاً كالمظا ئ ثرىرا رظا ئ ظل ظمب رضاظمثاً ظاً رضؤيرظاً كرض الرظا ىظا ثيظم ر ظا . ياصف ثل ل رضؤيراً كرض الرا انها حظاة ك ظاةم كقايعرظة.رضجانبرة رضىخرفة كغرم رضىالباضة ضهتر رضناع ل رضعالج في حدكة ع ككشميل ساكة ل درية رضىعاضجة رضكرىرا رة ك ظا رضؤيرظاً كرض الرظا رضى ظاةمemesis كيحدث رض الرا رضحاة ظا رض الرظا.ع ككشميل ساكة ل دء رضىعاضجة رضكرىرا رة كيد يا ىم ضىظد قصظل لضظذ سظباع كرحظد فربد عد مك رض ايعي فإنه يحدث يبل رضبدء اضىعاضجة رضكرىرا رة كيحدث ذضك كند رضىماظذ رضظتيل ي ايعظاً حدك ظه حاظ رضىشظهد ك ق ارمظد ناريظل كصظبرة خ عفظة فظي ثظل ظل.رضمكر ح ك قتثم رضىكاً رضتي حصعت فره ته رضحاضظة ظل رضؤيرظاً كرض الرظا رضالنا رضهضىرة كرضجهاز رضعصبي رضىمثزي ي م ل ةالضهظا قاصظرل فاظراضامرا ظمب رضؤيرظاً كرض الرظا رضظتي يظ م حفظزه قشظظىل ظظته رضناريظظل رضعصظظبرة ثظظل ظظل ةك ظظا رل ك راظ ا رل ك سظظر رل ثظظاضرل كسظظرمكقانرل.ارسظ ة رضعظظالج رضكرىرظظا ي ) رض ي قا م صا باشم كغرم باشم كعذ مثظز رض الرظا رضىامظاة فظي رضجظزءsubstance P( اإلاافة لضذ اة ب كيالظا رضنشظاث رضحرظاي.رضجانبي رضشبكي ل رضنخاع كقع بظم ظاة ب حظد فظمرة كا عظة رض اثركرنظاب ضعبرب رظدرب رضعصظبرة ) رضىاماة في ثل ل رضالنظا رضهضظىرةNK1( ضهته رضىاة حفز رض الرا رضتي قم قاصرعه ارس ة ا البالب نرا كثرنرل ًكرضجهاز رضعصبي رضىمثزي حرث يعع ثل ل ا البالب يا كثرنرل ك ظاة ب ةك ر ئ كراظحا ئ فظي ظدء حظدكث رضؤيرظا .كرض الرا رضتي ي م حفزه ارس ة ةكية رضىعاضجة رضكرىرا رة Most patients who undergo chemotherapy have noted that nausea and vomiting are the most feared and distressing side-effects of cancer treatment (1). Nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy can be classified as acute, delayed, or anticipatory. Acute emesis generally occurs within 24 hours of chemotherapy administration; while delayed nausea and vomiting begin 24 hours after chemotherapy and may continue for up to one week. Anticipatory emesis occurs prior to chemotherapy in patients who anticipate another episode by sight, odors, or memory of the place where acute nausea and vomiting occurred (2,3). Different neurotransmitters found in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and central nervous system (CNS) mediate the pathophysiology of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV).These include dopamine, histamine, acetylcholine, serotonin, and substance P; which act directly and indirectly on the vomiting center located in the lateral reticular formation of the medulla (1,4). Substance P is a member of the tachykinins family of neuropeptides.The biological activity of this substance is to induce vomiting mediated by neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptors located primarily in the GIT and the CNS (5). Both NK1 receptors and substance P play a significant role in the pathogenesis of acute and delayed CINV. Introduction The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines suggest that the potential effect of CINV is influenced by the emetogenicity level of the chemotherapeutic agent and patient characteristics. Coadministration of chemothera-peutic agents and repeated cycles of chemotherapy increase the Department of Pharmacy Practice, North Dakota State University 123D Sudro Hall, Fargo, North Dakota 58105, USA E-mail: Mohammed.Aseeri@ndsu.edu Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, Vol. 14, No. 1 January 2006 risk of CINV. Furthermore, patient characteristics can increase the risk for CINV; adults under 50 years old, female patients, children, and those with a history of motion sickness are more likely to have CINV (6, 7). Currently an antagonist of 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 receptors (5-HT3) (e.g. ondansetron) in combination with oral dexametha-sone is used to control acute emesis after highly emetogenic chemotherapy (3). However, the 5-HT3 antagonists do not show efficacy against delayed emesis. Although the effectiveness of the current antiemetic agents has controlled and decreased the incidence APREPITANT and severity of CINV, nausea and vomiting continue to occur on a regular basis. The pathophysiology of delayed emesis is still not completely understood and difficult to control. It has been estimated that up to 80% of patients receiving cisplation at doses of 50 mg/m² or higher experience delayed nausea and vomiting despite good control of acute emesis.3 Hence, newer antiemetic agents that can control delayed emesis are needed. Aprepitant (Emend®, Merck and Co Inc) is an antagonist of substance P that blocks NK-1 receptors. This drug was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April, 2003, for the prevention of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting associated with initial and repeat courses of highly emetogenic cancer chemotherapy, including highdose cisplatin (8). It represents a new class of antiemetics, the NK-1 receptor antagonists. Aprepitant in combination with other antiemetics such as 5-HT3 antagonists and oral dexamethasone has demonstrated efficacy in the control of both acute and delayed nausea and vomiting for patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Approval of aprepitant by the FDA was based on two multicenter, randomized, parallel, double-blind, controlled clinical studies. More than 1100 cancer patients receiving a chemotherapy course with highdose cisplatin ≥ 70 mg/ m² were randomized to either the aprepitant regimen (N=550) or the standard therapy (N=555); the primary endpoint was to achieve a complete response (defined as no emetic episode and no use of rescue therapy) during the five-day period after cisplatin therapy. The aprepitant regimen consisted of an oral dose of aprepitant 125 mg, an intravenous dose (IV) of ondansetron 32 mg (5-HT3 antagonist), and oral dexamethasone 12 mg on Day1; oral aprepitant 80 mg and an oral dexamethasone 8 mg once daily on Day 2-3; and oral dexamethasone 8 mg on Day 4. This regimen was compared with standard therapy which included oral dexamethasone 20 mg plus IV ondansetron 32 mg on Day 1, and oral dexamethasone 8 mg twice daily on Day 2-4. Both studies found that the percentage of patients who achieved complete response on day 1 to day 5 was significantly higher in the aprepitant groups versus the standard therapy [study 1 (72.7% vs. 52.3%); study 2 (62.7% vs. 43.3%), respectively] (5, 9). The frequency of delayed emesis was significantly improved in the aprepitant group compared to standard therapy 75.4% vs. 55.8%, respectively, in Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, Vol. 14, No. 1 January 2006 85 the first study and 67.7% vs. 46.8%, respectively in the second study (both studies were P<0.001). Based on data obtained from these two studies researchers concluded that aprepitant in combination with a 5HT-3 antagonist and dexamethasone has a significant effect and provides superior antiemetic protection against CINV associated with highly emetogenic cancer chemotherapy in acute and delayed emesis compared with standard therapy. Recent studies noted that the incidence of CINV is approximately 41% in patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC) (10) such as cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and epirubicin. Therefore, more effective treatments to prevent CINV in patient receiving MEC, especially in those who are particularly more susceptible to CINV, are needed. Using aprepitant in patients receiving MEC was evaluated recently in breast cancer patients treated with cyclophosphamide-based chemothe-rapy (11). Results suggested the addition of Emend to ondansetron and oral dexamethasone improved the prevention of emesis during the acute and delayed phases compared to the control regimen of ondansetron and dexamethasone alone ( 50.8% vs. 42.5%; P=0.019). Due to the lower potential emesis with MEC agents, the difference between the aprepitant group and the control group was smaller compared to highly emetogenic chemotherapy, but it was still clinically important. Further studies will determine the appropriateness of using aprepitant with MEC. Clinical trials proved that aprepitant is a safe antiemetic drug, and most of the adverse effects reported were described as mild to moderate in intensity: 10-12% of patients experienced fatigue, asthenia, dizziness, constipation, diarrhea, anorexia, and hiccups (4). Based on data obtained from studies done in animals, aprepitant is rated as FDA pregnancy category B; however, the potential benefit of using this drug should outweigh the risk (8). Aprepitant is a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor; therefore, caution is recommended in patients receiving concomitant medications including chemotherapy agents that are primarily metabolized by this system (e.g., ifosfamide, cyclophosphamide, ketoconazole, corticosteroids) (2). Inhibition of CYP3A4 by aprepitant could result in elevated plasma concentrations of these concomitant drugs, leading to serious or life-threatening reactions (8). Also, this drug is an inducer of CYP2C9 and can lower levels of warfarin and oral contraceptives. 86 Coadministr-tion of aprepitant with warfarin may result in a clinically significant decrease in the International Normalized Ratio (INR); therefore, INR should be assessed within 7-10 days of therapy in patient receiving warfarin therapy. In addition, the efficacy of oral contraceptives may diminish during and for four weeks following the last dose of aprepitant. Thus, an alternative form of birth control should be used for at least one month after the last dose of aprepitant.(2). Emend undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism in the liver primarily through CYP3A4; therefore, use with caution in hepatic dysfunction is recommended, as data are very limited in those patients. The metabolized form of this drug is excreted in urine and feces in approximately equal parts, and due to this limited amount that is excreted unchanged in urine, no dose adjustment is necessary in patients with renal disease or end-stage renal failure maintained on hemodialysis (4, 8). To date, safety and effectiveness of aprepitant in pediatric patients have not been established as most patient in clinical trials were either adults, or geriatrics.4 Aprepitant comes as a 3-day tripack containing 125 mg capsule for the first day and two 80 mg capsules for the second and third day. In United States the average wholesale price of a 3-day course is $312, which seems costly (12). However, failure to control CINV after highly emetogenic chemotherapy can increase health care costs because of the need for hospitalization or hydration and replacement of electrolytes lost during vomiting (4). Therefore, results obtained from clinical trials of using this drug with 5-HT3 antagonist and dexamethasone in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy may justify the drug cost. Patients should take a 125 mg capsule on the first day 30-60 minutes before chemotherapy, then 80 mg capsules on day 2 and 3. Aprepitant must be taken with a 5-HT3 antagonist and dexamethasone for 3 days with each cycle of chemotherapy. Pharmacists are in a position to provide accurate and useful information to patients regarding drug therapy. Patients should be counseled about the dosing schedule of aprepitant, and not to take the drug alone to prevent CINV, also most common adverse effects of aprepitant use should be reviewed. Aprepitant may interact with some drugs include non-prescription and herbal supplements; therefore, patients should be advised to inform their doctor if they start or stop any medications. Women Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, Vol. 14, No. 1 January 2006 ASEERI who use oral contraceptives should be instructed to use alternative or back-up methods of contraception during and for one month after the last dose. References 1. Navari RM. Role of neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists in chemotherapy-induced emesis: summary of clinical trials. Cancer Invest. 2004; 22(4):569-76. 2. Viale PH. Integrating aprepitant and palonosetron into clinical practice: a role for the new antiemetics. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2005; 9(1):77-84. 3. Sharma R, Tobin P, Clarke SJ. Management of chemotherapy -induced nausea, vomiting, oral mucositis, and diarrhoea.Lancet Oncol. 2005; 6(2):93-102. 4. Massaro AM, Lenz KL. Aprepitant: a novel antiemetic for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Ann Pharmacotherapy. 2005; 39(1):77-85. Epub 2004 Nov 23. 5. Hesketh PJ, Grunberg SM, Gralla RJ, Warr DG, Roila F, de Wit R, Chawla SP, Carides AD, Ianus J, Elmer ME, Evans JK, Beck K, Reines S, Horgan KJ. The oral neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapyinduced nausea and vomiting: a multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin--the Aprepitant Protocol 052 Study Group.J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21(22):4112-9. Epub 2003 Oct 14. 6. Gralla RJ, Osoba D, Kris MG, Kirkbride P, Hesketh PJ, Chinnery LW, Clark-Snow R, Gill DP, Groshen S, Grunberg S, Koeller JM, Morrow GR, Perez EA, Silber JH, Pfister DG. Recommendation for the use of antiemetics: evidence-based, clinical practice guidelines. American Society of Clinical Oncology.J Clin Oncol. 1999; 17(9):2971-94. No abstract available. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol 1999 Dec; 17(12):3860. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18(16):3064. 7. Osoba D, Zee B, Pater J, Warr D, Latreille J, Kaizer L. Determinants of postchemotherapy nausea and vomiting in patients with cancer. Quality of Life and Symptom Control Committees of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group.J Clin Oncol. 1997; 15(1):116-23. 8. Emend, Merck& Inco Package insert. 2003. 9. Poli-Bigelli S, Rodrigues-Pereira J, Carides AD, Julie Ma G, Eldridge K, Hipple A, Evans JK, Horgan KJ, Lawson F. Addition of the neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist aprepitant to standard antiemetic therapy improves control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Latin America. Cancer. 2003 15; 97(12):3090-8. 10. Grunberg SM, Deuson RR, Mavros P, Geling O, Hansen M, Cruciani G, Daniele B, De Pouvourville G, Rubenstein EB, Daugaard G. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis after modern antiemetics. Cancer. 2004; 100(10) :2261-8. 11. Warr DG, Hesketh PJ, Gralla RJ, Muss HB, Herrstedt J, Eisenberg PD, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with breast cancer after moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23(12):2822-30. 12. Redbook. Montvale, NJ: Thompson medical economic, 2004.

![[Physician Letterhead] [Select Today`s Date] . [Name of Health](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006995683_1-fc7d457c4956a00b3a5595efa89b67b0-300x300.png)