Pax Romana: Contributions to Society

advertisement

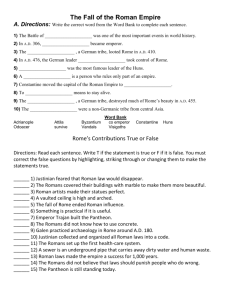

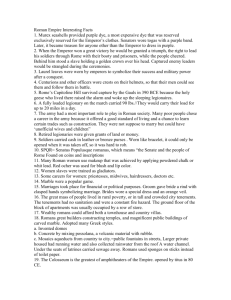

Station 1 Art and Architecture In its early days, Rome absorbed ideas from Greek colonists in southern Italy, and it continued to borrow heavily from Greek culture after Rome conquered Greece. Over time, Romans adapted and transformed Greek and Hellenistic achievements just as the Greeks had once absorbed and blended ideas and beliefs from Egypt and the Fertile Crescent. The mixing of Greek, Hellenistic, and Roman traditions produced what is known as Greco-Roman civilization. Roman buildings combine both Greek and Roman elements and ideas. Roman builders used Greek columns. However, immense palaces, temples, stadiums, and victory arches stood as mighty monuments to roman power and dignity. The Romans improved on devices such as the dome and the arch. One of the most amazing features of Roman architecture was the vaulted ceiling. Two of Rome’s most famous buildings erected during the Pax Romana were the Pantheon and the Colosseum. The Pantheon is Rome’s most famous domed structure and is a magnificent temple to all Rome’s gods. The Colosseum was built of concrete and faced with stones. Romans were the first to use concrete, and by only covering the outside of the Colosseum with stones it was much cheaper and easier to build. The Colosseum was used for gladiator fights, mock naval battles, and other sporting events. The Colosseum could hold about 50,000 spectators. Most of our modern stadiums are built along the same format. The Romans designed the Colosseum so precisely that it could be filled in 15 minutes and evacuated in 5! The Roman Forum The forum was the main marketplace and business center, where ancient Romans went to do their banking, trading, shopping, and marketing. It was also a place for public speaking. The ancient Romans aspired to be great orators. The job of their orators was not to argue, but to speak persuasively. The Forum was also used for festivals and religious ceremonies. It was a very busy place. The Forum in Ancient Rome The Forum today Roman Schools The Goal of education in ancient Rome was to be an effective speaker. The school day began before sunrise, as did all work in Rome. Kids brought candles to use until daybreak. The school year began each year on March 24th. Children were first home-schooled in law, history, customs, reading, and writing by their father. Girls were taught by their mother to spin, weave, and sew. At the age of 6 or 7, all boys and some girls went to school to learn reading, writing, and counting. Later they went to grammar school, where they studied Latin, Greek, grammar, and literature. School was not free, so most poor children (most of the population) could not attend. Station 2 Writing and Theater The language spoken in Rome was Latin. It is a significant language because it is the basis for all the romance languages. Romance languages include French, Spanish, Italian, and Greek. In literature, educated Romans admired the Greeks. Many spoke Greek and imitated Greek styles in prose and poetry. Still, the greatest Roman writers used Latin to create their own literature. Authors during the Pax Romana generally wrote either fictional or historical literature. An example of fictional literature from the time is Virgil’s epic poem, the Aeneid. Virgil tried to show that Rome’s past was as heroic as that of Greece. Roman historians pursued their own theme: the rise and fall of roman power. The historian Livy sought to rouse patriotic feelings and restore traditional roman virtues to society by recalling images of Rome’s glorious past as a republic. In his story of Rome, Livy recounted the tales of great heroes such as Cincinnatus. Theaters In Ancient Rome, plays were presented at the time of the games on contemporary wooden stages. The first such permanent Roman theater was ordered to be built by Pompey in 55 BC, eventually erected on the Campus Martius at Rome. Built of stone, it had a seating capacity of 27,000. Essentially patterned after the Greek theater, it differed in the respect that it was built on level ground. Excavated out of the sides of hills, the circular space located in front of the stage in a Greek theater was called the orchestra, where choruses and actors performed. Since Roman plays usually lacked a true chorus, the area in front of the stage which might have been an orchestra simply became a semicircular area. All actors in Roman plays were male slaves. Men played the parts of women. The typical stock characters included the rich man, the king, the soldier, the slave, the young man, and the young woman. If necessary, an actor would play two or more roles in a single performance. The most notable part of an actor's regalia was probably his mask. While different masks and wigs were used for comedies than tragedies, certain characteristics remained constant. All masks had both cheek supports and special chambers which acted as amplifiers. Gray wigs represented old men, black for young men, and red for slaves. Young men donned brightly colored clothing, while old men wore white. In this manner the characters could be easily identified by the audience. Admission to the Roman plays was free for citizens. Originally, women were barred from viewing comedies and were only admitted to tragedies, but later, no such restrictions were imposed. Pantomimes, popular during the 1st century BC, involved miming roles to accompaniment of singers, dancers, and musicians, in addition to visual effects, similar to a ballet. In mimes of antiquity actors spoke. Women were allowed in mimes and pantomimes, which were more popular than typical plays but eventually degenerated into vulgar and disgusting tastelessness. Station 3 Sport and Leisure Rich and poor alike loved spectacular entertainment. At the Circus Maximus, Rome’s largest race course, chariots thundered around an oval track, making dangerously tight turns at either end. Fans bet feverishly on their favorite teams—the Reds, the Greens, the Blues, or the Whites—and successful charioteers were hailed as heroes. Chariot racing was Rome’s oldest and most popular pastime, dating back to before the Republic. Greek chariot races were held in the hippodrome in the east, but in the west they were held in circuses. If successful, a charioteer could become rich and famous throughout Rome. Images of charioteers survive in sculpture, mosaic, and molded glassware. The different colored teams were rivals, sometimes leading to violence among supporters. The Greens and the Blues were overall favorites. The circus itself was built around a u-shaped arena. At the open end of the “u” waited up to twelve fourhorse chariots, which began the race from the starting gates. They raced around the course counterclockwise for seven laps. Gladiators Several different types of shows all took place in the arena of an Amphitheater. The word arena comes from the Latin for "sand," which was placed on the Amphitheater floor to soak up spilled blood. Amphitheaters were most commonly used for gladiatorial matches which had been adapted from Etruscan funeral rites (munera). By the last 1st century BC, however, the games had lost their ritualistic significance. Gladiators came from various lots of life. Originally, there were gladiatorial schools, but these came under state control in the 1st century BC to avoid them becoming private armies. The majority of gladiators were either condemned criminals (damnati), slaves, prisoners of war, or volunteers who signed up to do shows for a fee. There were four main types of gladiator: Murmillo: Fought with a helmet adorned by a fish crest, an oblong shield, and a sword. He usually fought a retiaritus. Retiaritus: A lightly armed gladiator with a net, brandishing either a trident or a dagger. Samnite: Utilized a sword, visor and helmet, and an oblong shield. Thracian: Combated with a curved scimitar and round shield. Various other weapons, women, and sometimes even dwarves were used in the games. Special types of "wild animal matches" (venationes) were introduced in the 2nd Century BCE and became very popular. Such bouts included men on foot and on horseback, known as beastiarii, who were usually either criminals, prisoners of war, or trained and paid fighters. Beastiarii fought exotic animals, which eventually led to an extensive trade market. Originally, wild animal matches took place on the morning of the games, the public executions were held at midday, and then the gladiatorial matches. Over time, however, these divisions became blurred, and often many fights would take place at once, giving the appearance of a battle. Other spectacles included mock naval battles (naumachiae), known to take place on artificial lakes, as well as animal performances, accompanied by music. Magistrates used private games to gain support in elections. The emperors successfully continued this practice and the games became more lavish as each tried to out-do is predecessor. Enormous amounts of money were spent on games, yet they were free to the people. To emperors who paid for them with taxes, these amusements were a way to control the city’s restless mobs. In much the same spirit, the government provided free grain to the poor. Critics warned against this policy of “bread and circuses” but no one listened. During the Pax Romana the general prosperity hid underlying social and economic problems. Later Roman emperors, however, would face problems that could not be brushed away so easily. Other Leisure Activities For the wealthy, entertainment could take place at home as they hosted their own dinner parties and lavish banquets. Along with dinner could be music, singing, and dancing by professionals. In some circles, recitation of written work, such as poetry and speeches, followed. For the plebeians, associations (collegia) may have thrown dinner parties. Eating and drinking for the poor usually meant frequenting taverns, ranging from brothels to gaming houses and everything in-between. Gaming was popular among all classes, and included pastimes such as dice, knucklebones, and gaming counters. Board games were played by adults as well as children. Traditional children's games, such as hide-andgo-seek and leap frog are depicted in Ancient Roman art. Children's toys have also been found. For the wealthy, hunting and fishing may have provided leisurely sport, but for the poorer these activities were more often a necessity. The expression "you are what you eat" could not have been more true than at Ancient Rome. While plebeians sustained themselves on cereals and bread, members of the senatorial class dined on exotic foods from faraway lands and enjoyed three course meals over luxurious dinners. Wine, anyone? Food and Drink For the majority of persons dining in Ancient Rome, meals were centered around corn (grain), oil and wine, and, for the wealthy, different types of exotic foods. Cereals were the staple food, originally in the form of husked wheat (far) being made into porridge (puls), but later naked wheat (frumentum) was made into bread. Bread was the single most often eaten food in Ancient Rome, and was sometimes sweetened with honey or cheese and eaten along with sausage, domestic fowl, game, eggs, cheese, fish, or shellfish. Fish and oysters were especially popular; meat, particularly pork, was in high demand as well. Elsewhere in Rome, delicacies, such as snails or dormice, were specially bred. A variety of cakes, pastries, and tarts was baked commercially and at home, often sweetened with honey. Vegetables, such as cabbage, parsnips, lettuce, asparagus, onion, garlic, marrows, radishes, lentils, beans, and beets were imported. Fruits and nuts were also available to the consumer, as was a variety of strongly flavored sauces, spices, and herbs, which became very popular in Roman cuisine. Our knowledge of Romans' dieting habits comes from literary references, archeological evidence, and paintings. The only true literary source ever devoted to Roman food was a cookbook attributed to Apicus. Romans loved wine, but they drank it watered down, spiced, and heated. Undiluted wine was considered to be barbaric, and wine concentrate diluted with water was also common. Pasca was probably popular among the lower classes. It was a drink made from watering down acetum, low quality wine similar to vinegar. Beer and mead were most commonly drunk in the Northern provinces. Milk, typically from sheep or goats, was considered to be barbaric and was therefore reserved for making cheese or medicines. Cooking Bread, cakes, and pastries were cooked commercially and at home in Ancient Rome. A circular domed oven was used mainly for bread and pastries. Most food was cooked over an open hearth, either by means of cauldrons suspended from chains or cooking vessels set on gridirons. Cooking was done in the kitchen, where smoke could escape out a small hole in the ceiling our through a wall vent. Cooking was also known to be done outside, and for those living in tenements, communal ovens may have been available. Food was often prepared with a mix of fruit, honey, and vinegar, to obtain a sweet-sour flavor, and most meat was broiled. Preservation of foods was difficult, and so popular foods, such as fish and shellfish, were probably shipped live to their destination. Some foods, however, such as meat and fish, could be preserved after a tedious process of pickling, drying, smoking, and salting. Food poisoning was probably a commonplace affair. Meals Romans generally ate one large meal daily. Breakfast (ientaculum), if taken, was a light meal at best, often nothing more than a piece of bread. This was followed by the main meal of dinner (cena) at midday, and a small supper (vesperna) in the evening. Later, however, it came to pass that dinner was eaten as a large meal in the evening, replacing supper and adding a light lunch, or prandium. For the poor, meals consisted of porridge or bread with meat and vegetables, if available. For the wealthy, the meal was divided into three courses (ab ovo usque ad mala - from egg to apples). The 1st was an appetizer made of simply eggs, fish, shellfish, and raw vegetables known as gustatio or promulsis. The main course, prima mensa, consisted of cooked vegetables and meats, based on what the family could afford, and was followed by a desert (secunda mensa) of fruit and/or sweet pastries. The Romans sat upright to eat, but the wealth often reclined on couches at dinner parties, or ate outside in gardens, with the weather permitting. For the poor, tableware probably consisted of coarse pottery, but for those willing to spend a slightly prettier penny, tablewares could be purchased in fine pottery, glass, bronze, silver, gold, and pewter. Food was eaten with the fingers and cut with knives crafted from anter, wood, or bronze with an iron blade. Bronze, silver, and bone spoons existed for eggs and liquids. These spoons had pointed handles that could be used to extract shellfish and snails from their shells. The recipes below show what wealthy Romans would have consumed on special occasions. Stuffed Kidneys - Serves 4 8 lambs kidneys. 2 heaped tspn fennel seed (dry roasted in pan). 1 heaped tspn whole pepper corns. 4 oz pine nuts. 1 large handful fresh coriander. 2 tbspn olive oil. 2 tbspn fish sauce. 4 oz pigs caul or large sausage skins. Skin the kidney, split in half and remove the fat and fibres. In a mortar, pound the fennel seed with the pepper to a coarse powder. Add this to a food processor with the pine nuts. Add the washed and chopped coriander and process to a uniform consistency. Divide the mixture into 8 and place in the centre of each kidney and close them up. If you have caul use it to wrap the kidneys up to prevent the stuffing coming out. Similarly stuff the kidney inside the sausage skin. Heat the oil and seal the kidneys in a frying pan. Transfer to an oven dish and add the fish sauce. Finish cooking in a medium oven. Serve as a starter or light snack with crusty bread and a little of the juice. Pear Patina - Serves 4 1½ lb firm pears. 10fl oz red wine. 2 oz raisins. 4 oz honey. 1 tspn ground cumin. 1 tbspn olive oil. 2 tbspn fish sauce. 4 eggs. plenty of freshly ground black pepper. Peel and core the pears and cook in the wine, honey and raisins until tender. Strain and process the fruit and return to the cooking liquor. Add the cumin, oil and fish sauce and the eggs well beaten. Pour into a greased shallow dish and bake in a preheated oven (375º F) for 20 mins or until set. Let the custard stand for 10 mins before serving warm. Libum - Serves 2 10 oz ricotta cheese. 1 egg. 2½ oz plain flour. Runny honey. Beat the cheese with the egg and add the sieved flour very slowly and gently. Flour your hands and pat mixture into a ball and place it on a bay leaf on a baking tray. Place in moderate oven (400ºF) until set and slightly risen. Place cake on serving plate and score the top with a cross. our plenty of runny honey over the cross and serve immediately. Station 4 Government and Society During the Pax Romana, the government was run by an emperor who had total control. The emperors’ main responsibilities included maintaining order, enforcing the laws, defending the borders, and providing relief in the event of natural disaster (as in the case of the eruption of Vesuvius). Like in the Republic before it, the Empire was divided into provinces controlled by governors. Unlike the Republic, the emperor maintained control over the governors and unified Rome through uniform laws. Like every nation, Rome had its share of good and bad leaders. Here are just a few… The Bad Caligula (37-41 CE) After Tiberius dies in Capri, Gaius Caesar is named emperor. 'Caligula', more properly Gaius (Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus), was the third Roman emperor. He is remembered in history as one of Rome’s worst emperors. Caligula was the son of a popular Roman general, who was killed by the emperor Tiberius. He got his name Caligula (“little boots” in Latin) from his father’s soldiers. Caligula grew up with Tiberius at his palace on the island of Capri, and took power after Tiberius’ death (Caligula may have helped kill him by smothering him with a pillow). The 24-year-old emperor was at first very popular. He provided exciting, generous games for the Romans to enjoy, and got rid of some taxes. The army liked him because he was the son of a general. He got sick early in his rule, and once he was healthy again, he acted very cruelly toward his people and the Senate. To embarrass the Senate, he made his horse a senator. He also insisted on being treated as a god. At home in Rome, Caligula abused the wives of Roman senators, and had many people executed, including the families of some of his guards. He had his elderly uncle thrown in a river in February to “see if he could swim.” In 39-40 AD, Caligula sent his armies to fight in Germany, but they did not gain any land. He also sent troops to fight in England, but they did not make it there, and instead of fighting he told them to gather seashells along the English Channel. He had parades and celebrations to show off his “victories.” These actions were expensive and a waste of time, and made the army and the Praetorian Guard start to hate him. By the year 41, Caligula had made too many enemies and the Praetorian Guard killed him, along with his wife and the rest of his family, because they did not want anyone to be able to follow him on the throne, or to get in trouble for their actions. They put his uncle Claudius on the throne after him, and he ruled for 13 years. Nero (54-68 CE) Nero came to power through the pressure of his mother, who bore over him throughout his life. He eventually had her killed, which caused him to be unpopular with the people. He offered the people bread and created public baths, which stopped some of the outcry. The Great Fire of Rome began on July 18 and lasted for six days and seven nights. Of Rome's 14 districts only four remain untouched. Rumors circulated that Nero had been singing and dancing while Rome burned. In order to divert attention away from himself, Nero blamed the Christians. He ordered some to be thrown to the lions; many others are crucified. Nero discovered that many people were conspiring to kill him, and he lashed out. The poets Lucan, Seneca and the novelist Petronius are among those who lost their lives in the purge that follows. Increasingly alone and paranoid, Nero kicks his wife Poppaea to death while she is pregnant and ill. Reportedly, this is for complaining that he came home late from the races. Support for Nero dwindled and he is declared a public enemy by the Senate, meaning anyone can kill him without being punished. Terrified, and abandoned by everyone, except a few of his slaves, Nero flees to the country. There he commits suicide, ending the dynasty of Augustus. His last words were, "Qualis artifex pereo." ("What an artist the world loses in me.") Tiberius (14-37 CE) Tiberius was a tragic figure. He was a great military commander—the best of his age—but he was neither interested in nor good at politics. Yet, because of his birth, he was doomed to be emperor. Stern, cold, reserved, formal. Strong sense of duty. He was a great leader in the field, with real talent. Tiberius' great flaw was that he was deeply suspicious of others. He was easily hurt and could be cold-blooded. He knew Augustus favored others over him and that he was about the eighth choice. It was his mother, Livia, who was determined that Tiberius should succeed. He himself was unenthusiastic about becoming emperor and ended by loathing his position. When Tiberius’ son died, he trusted only the Praetorian Guard. The guard took advantage of this, and had many people killed, claiming that the emperor wanted it. Tiberius did not pay attention to his people or the senators, so he did not listen to people who tried to tell him what was happening. Tiberius eventually had some of the guards killed when he realized they were trying to take power from him. He was convinced now that no one could be trusted. There followed a terrible period in which there were many political murders while Tiberius himself neglected the government more and more and amused himself at his country estates. During these last years, Tiberius paid too much heed to informers, believing the worst of everyone. Informers were paid for information and some managed to make their fortunes by accusing one powerful man after another of treason. Even the threat of such accusation was enough to receive bribes. There were many executions and fake trials. All the while, the emperor hid at the beautiful island of Capri, seldom visiting Rome. He grew older and increasingly withdrawn. Tiberius refused to name a successor to the throne, and he had no son to follow him. Tiberius' choice fell at last on a nephew, a young man well liked in Roman circles. When Tiberius died, Caligula was hailed as his successor. The Good Trajan (98-117 CE) Trajan came from Spain and was the first non-Roman to be emperor. He was a great general, and increased the territory of the Roman Empire. Trajan was a soldier at heart, happiest when he was out with his army. He brought more territory under Rome’s control, in places like Persia, Mesopotamia, and Britain, and kept the army well organized. He was emperor during the Second Jewish War, which caused the Jews to be removed almost completely from their homeland and scattered across the Empire—the famous Diaspora. The Roman Empire never covered more territory than it did under Trajan. This was also the Silver Age of Roman literature, with the most famous writers being Pliny the Younger and the historian Tacitus. A record of Trajan’s many accomplishments was recorded on a column, with the history of his feats winding around it from top to bottom. This is Trajan’s Column, which can still be seen in Rome. He was in charge during many important building programs, including an expansion of the Forum that is named after him, reconstruction of the Circus Maximus to a size that could hold 200,000 people, and the building of an entire new harbor at Ostia (Rome’s port town). Trajan had few enemies in his empire, so unlike many other emperors who were murdered, he died of old age. Trajan ruled for many years and expanded the empire more than any man since Tiberius. Perhaps as important as any other accomplishment, he was a good judge of character and chose his successor wisely: Hadrian. Hadrian (117-138 CE) A cultured scholar, fond of all things Greek, Hadrian travelled all over the empire. He was attentive to the army and the provincials, and left behind him spectacular buildings such as the Pantheon in Rome and his villa at Tivoli. But his greatest legacy to the empire was his establishment of its frontiers, marking a halt to imperial expansion. In Africa he built walls to control the transhumance routes, and in Germany he built a palisade with watch towers and small forts to delineate Romancontrolled territory. In Britain, he built the stone wall which bears his name, perhaps the most enduring of his frontier lines. He was truly a pivotal emperor, in that he divided what was Roman from what was not. Apart from minor adjustments, no succeeding emperor reversed his policies. Marcus Aurelius (161-180 CE) Marcus Aurelius was a clever emperor who was interested in new ideas and in philosophy. He thought all people were basically the same, in a world that is basically good. Unfortunately, as emperor, his main problems were to defend the empire’s borders against attacks, and deal with his son, Commodus, who was not a good person at all. Commodus’s idea of a good time was to dress up like a gladiator and kill people for fun. Marcus Aurelius is the last of the “Good Emperors” and the last emperor of the Pax Romana. Marcus Aurelius ruled at the same time as another emperor, because the previous emperor named two people to follow him. Marcus Aurelius had to fight to control Rome’s territory in the east in Parthia. He and his co-emperor had a strong army, but many of the soldiers got sick from a plague when they were away from Rome. They brought the disease back to Rome and it spread all over the peninsula. Invaders attacked Rome when it was weak from plague, but Rome was able to defeat them . Marcus Aurelius became the only emperor in 169 AD (CE). He did not make many big changes to Rome when he was in charge, but he did encourage people to study the law. He thought it was important to understand Rome’s laws and make sure they were fair. He also let people who the Romans saw as barbarians live in the empire. Marcus Aurelius led many military expeditions, and these cost a lot of Rome’s money. He spent nearly all of Rome’s money on the army, but he was not the only emperor to do that. Marcus Aurelius is known as being a philosopher-emperor. His “Meditations,” a book of philosophy he wrote, are still reproduced and read today. His writings were personal—he never intended that they be published—and they reveal a man both sensitive and determined. The Meditations is easy to read because it is nothing more than a collection of short thoughts. One of Marcus Aurelius’ meditations from his book was: “human beings exist for each other; either improve them, or put up with them!” Station 5 Roman Law “Let justice be done,” proclaimed a Roman saying, “though the heavens fall!” Probably the greatest legacy of Rome was its commitment to the rule of law and to justice—ideas that have shaped western civilizations today. The laws of Rome were intended to be impartial and humane. During the Republic, Romans made use of civil laws (jus civile), which are laws that applied to the citizens of Rome. As Rome expanded, however, it ruled many foreigners who were not covered under civil law. Gradually, a second system of law, known as the law of nations (jus gentium), emerged. It applied to all people under Roman rule, citizens or non-citizens. Later, when Rome extended citizenship across the empire, the two systems merged. During the Roman Empire, the rule of law fostered unity and stability. Many centuries later, the principles of Roman law would become the basis for legal systems in Europe and Latin America. As Roman law developed, certain basic principles evolved. Many of these are familiar to Americans today. Among them are these ideas… • People of the same status were guaranteed equal protection under the law • People were innocent until proven guilty • The accused should be allowed to face his or her accuser and defend against the charge • Guilt must be established “clearer than daylight” through evidence • Decisions should be based on fairness, allowing judges to interpret the law The Romans thought law should reflect principles of reason and justice, and should protect the citizens’ person and property. Their idea that law could be based on just and rational principles could apply to all people, regardless of nationality, was a major contribution. Station 6 Science and Engineering Romans excelled in the practical arts of building, perfecting their engineering skills as they built roads, bridges, and harbors throughout the empire. Roman roads were so solidly built that many of them remained in use long after Rome fell. In addition, three things that scientists were most interested in studying included public health, sanitation, and engineering. Roman engineers built many immense aqueducts, or bridge like stone structures that brought water from the hills into Roman cities. In Segovia, Spain, a Roman aqueduct still carries water along a stone channel supported by tiers of arches. The availability of fresh water was important to the Romans. Wealthy homes had water piped in, and almost every city boasted both female and male public baths. Here people gathered not only to wash themselves but also to hear the latest news and exchange gossip. The Romans are perhaps the most famous aqueduct builders of the ancient era. In fact, the word “aqueduct” is derived from the Latin words aqua (“water”) and ducere (“to lead”). Within a period of about 500 years, the Romans constructed eleven major aqueducts to supply Rome with water. The first Roman aqueduct, Aqua Appia, was built around 312 BCE. By the time the eleventh aqueduct, Aqua Alexandrina, was completed in 226 CE, Rome was being watered by 359 miles of aqueducts and was receiving about 50 million gallons of water each day. In addition to building aqueducts for Rome, the Romans also build aqueducts for regions throughout their empire, including France, Spain, and Northern Africa. Remains of most of these aqueducts still exist, and a few such as the one in Segovia, Spain, are still in use. Public Baths In the time of the Roman empire, baths were a place of leisure time during many Romans daily routine. People from nearly every class - men, women, and children - could attend the thermae, or public baths, similar to modern day fitness clubs and community centers. The two most well preserved baths of ancient Rome are the baths of Diocletian and Caracalla. Diocletian's baths cover an enormous 32 acres, and now, the ruins include two Roman churches, St. Mary of the Angels and the Oratory of St. Bernard. The baths of Caracalla cover 27 acres. Towards the center of the Roman baths, adjoining the dressing room, could be found the tepidarium, an exceedingly large, vaulted and mildly heated hall. This could be found surrounded on one side by the frigidarium, a large, chilled swimming pool about 200 feet by 100 feet, and on the other side by the calidarium, an area for hot bathing warmed by subterranean steam. Not only were the baths meant for leisure, but also, for social gathering. In addition to the bathing areas could be found portico shops, marketing everything from food, to ointments, to clothing. There were also sheltered gardens and promenades, gymnasiums, rooms for massage, libraries, and museums. Complimenting these scholarly havens were slightly more aesthetic marble statues and other artistic masterpieces. Roman Roads The Romans built roads so that the army could march from one place to another easily. They tried to build the roads as straight as possible, so that the army could take the shortest route through the empire. How the roads were built: 1. First, the army builders would clear the ground of rocks and trees. They then dug a trench where the road was to go and filled it with big stones. 2. Next, they put in big stones, pebbles, cement and sand which they packed down to make a firm base., 3. Then they added another layer of cement mixed with broken tiles. 4. On top of that, they then put paving stones to make the surface of the road. These stones were cut so that they fitted together tightly. 5. Kerb stones were put at the sides of the road to hold in the paving stones and to make a channel for the water to run away. It is often said that "all roads lead to Rome," and in fact, they once did. The road system of the Ancient Romans was one of the greatest engineering accomplishments of its time, with over 50,000 miles of paved road radiating from their center at the miliarius aurem in the Forum in the city of Rome. Although the Roman road system was originally built to facilitate the movement of troops throughout the empire, it was inevitably used for other purposes by civilians then and now. The Romans generally left scientific research to the Greeks, who were by that time citizens of the empire. While the Romans rarely did original scientific investigations, they did put science to practical use. They applied geography to make maps and medical knowledge to help doctors improve public health. Pliny the Elder, a Roman scholar, compiled volumes of encyclopedias on geography, zoology, botany, and other topics all based on the work of others.