6b. Nematode Anatomy

advertisement

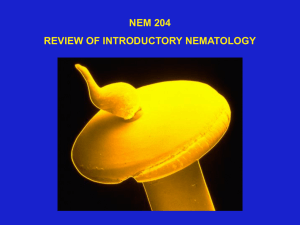

NEMATODA The phylum Nematoda is composed of a mixture of free-living and parasitic members. Nearly 20,000 species have been described in this vast phylum, but biologists estimate that there may be 4-50 times that number in existence. In fact, nematodes are so numerous that if you were to remove everything else from the environment, the remaining nematodes would form a ghostly skeleton outlining the entire terrestrial biosphere! Nematodes possess two major morphological advances over the flatworms you studied in the previous chapter. They have a pseudocoelom, a body cavity that lies between a layer of mesoderm and a layer of gastrodermis, and a complete digestive tract containing both a mouth and an anus. The evolutionary advantages of each of these characteristics are discussed later. Whereas flatworms show tremendous diversity in body form, nematodes tend to display more similarities than differences among the numerous species. They all possess unsegmented, tapered, tubular bodies devoid of appendages and covered by a thin cuticle secreted by the epidermis. The cuticle is permeable only to water, gases and some ions and thus serves as a protective coating, especially in parasitic forms. Another difference between nematodes and flatworms is that in nematodes the sexes are usually separate (dioecious) and females are generally larger than males. A unique characteristic of this phylum is that each animal has a finite number of cells in its body and this number is species specific (meaning that every member of the same species has the same number of cells, but different species may have different cell numbers). Cell division stops fairly early during embryonic development in nematodes and future growth during later developmental stages is achieved through cell growth (rather than through cell division). One common free-living nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans, is transparent throughout development, making it possible for biologists to trace the lineage of every cell from the zygote to the adult worm. Biologists have constructed a fate map of the lineage of all 959 cells in this roundworm and have recently sequenced its entire genome, making it the first multicellular organism to have its entire genetic sequence decoded. Although nematodes are usually only a few millimeters thick, they may range in length from a few millimeters to several meters. One parasitic species that inhabits the placenta of female sperm whales may attain a length of 9 meters! The infectious potential of parasitic nematodes is staggering. For instance, in Africa alone, 40 million people are presently infected with the larva of Onchocerca spp., a nematode which migrates to the victims’ eyes causing blindness. Onchocerca infection is currently one of the major causes of blindness worldwide. The disease commonly referred to as elephantiasis results from blockage of the lymphatic system brought about by one of several nematode species. This affliction causes substantial buildup of fluid and subsequent dense growth of connective tissue, grossly deforming various body regions. This condition is one of the world’s fastest spreading diseases and presently afflicts nearly 100 million people, particularly children, in temperate regions of the globe. Not only are their sheer numbers bewildering, but their ability to reproduce in large numbers is equally impressive. A single female Ascaris releases some 200,000 fertilized eggs per day (that’s 73 million per year!) Females of the guinea worm, Dracunculus medinensis, live just beneath the skin in their human hosts. When the skin comes into contact with water (as when the host bathes), the nematode protrudes is caudal end through the sore on the host’s skin and can eject up to 1.5 million offspring into the water during the course of a day. These offspring cannot directly reinfect humans, but instead carry out the lifecycle in a species of microscopic aquatic crustacean. Humans are infected when they drink the water containing these tiny arthropods. The cure for this infection is simple but tedious. An incision is first made in the skin of the host near the sore and the one-meter worm is slowly rolled out on a match stick a few centimeters daily until the entire worm has been removed. Nematode Anatomy 1. Obtain a preserved specimen of the roundworm Ascaris lumbricoides. This is a large, parasitic roundworm that infects humans and pigs. Be very careful when handling preserved nematodes. Nematode eggs are extremely resilient and may remain viable even after the females have been preserved. Keep your hands away from your eyes, nose and mouth to avoid possible contamination. 2. First determine the sex of your nematode. Males are typically smaller, have a curved caudal end and have two small, spiny projections called spicules on the ventral surface near the anus. These spicules are used during copulation. 3. After you have identified the sex of your specimen, differentiate between the cranial and caudal ends. This is more apparent on the males due to their curved tails. The cranial end of both sexes is generally more pointed than the more blunt caudal end. The anus is located on the ventral surface rather than at the terminal portion of the tail—another useful feature for distinguishing which end is which. 4. Use a dissecting scope to examine the cranial end of your specimen. Notice the triradiate mouthparts (lips) surrounding the mouth. This is a distinguishing feature of the phylum. 5. Use a dissecting needle to gently scrape away a piece of the thin cuticle from the body. Notice that it is composed of a transparent, proteinaceous substance. In parasitic species such as Ascaris, this cuticle protects the animals from the digestive enzymes of the host. 6. Submerge your specimen in water in your dissecting pan and use a sharp dissecting needle to make an incision through the body wall of the nematode near the mouth. Keeping the roundworm immersed in water, draw the needle along the length of the roundworm, extending the incision the entire length of the body. 7. Use several pins to carefully open your specimen and secure it to the pan. HINT: Pin your specimen near one edge of the dissecting pan so that you can easily view it under the dissecting scope. 8. Use the following figures and Table 10.3 to identify the internal anatomy of Ascaris. 9. View slides ZE 2-121 & ZE 3-12. Table 10.3 • Anatomy of a Roundworm (Ascaris) Structure Function Mouth Ingestion of food Pharynx Muscularized region of digestive tract that “pumps” food through the mouth and into the intestine Intestine Ribbon-like digestive tract where absorption of nutrients occurs Anus Elimination of indigestible wastes (egestion) Lateral lines Longitudinal canals that function as the excretory system of the roundworm, releasing nitrogenous wastes in the form of ammonia and urea Pseudocoelom Body cavity lined on the inside by a layer of gastrodermis and on the outside by a layer of mesoderm Testis (male) Produces sperm Ductus deferens (male) Stores mature sperm and transports them to seminal vesicle Seminal vesicle (male) Enlarged tube representing terminal portion of male reproductive tract which transports mature sperm out of the nematode Genital pore (female) Point of entry for sperm and opening through which fertilized eggs are released from the body Vagina (female) Terminal portion of female reproductive tract which receives sperm from males and directs eggs through genital pore Branched uterus (female) Site where developing eggs mature before being released Oviduct (female) Repository for eggs produced in ovary until fertilization Ovary (female) Produces eggs