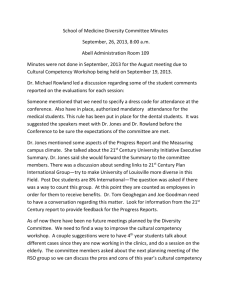

Title: The History of Tom Jones, a foundling

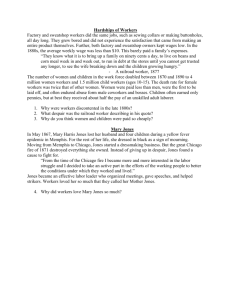

advertisement