ICPS Research Summary

advertisement

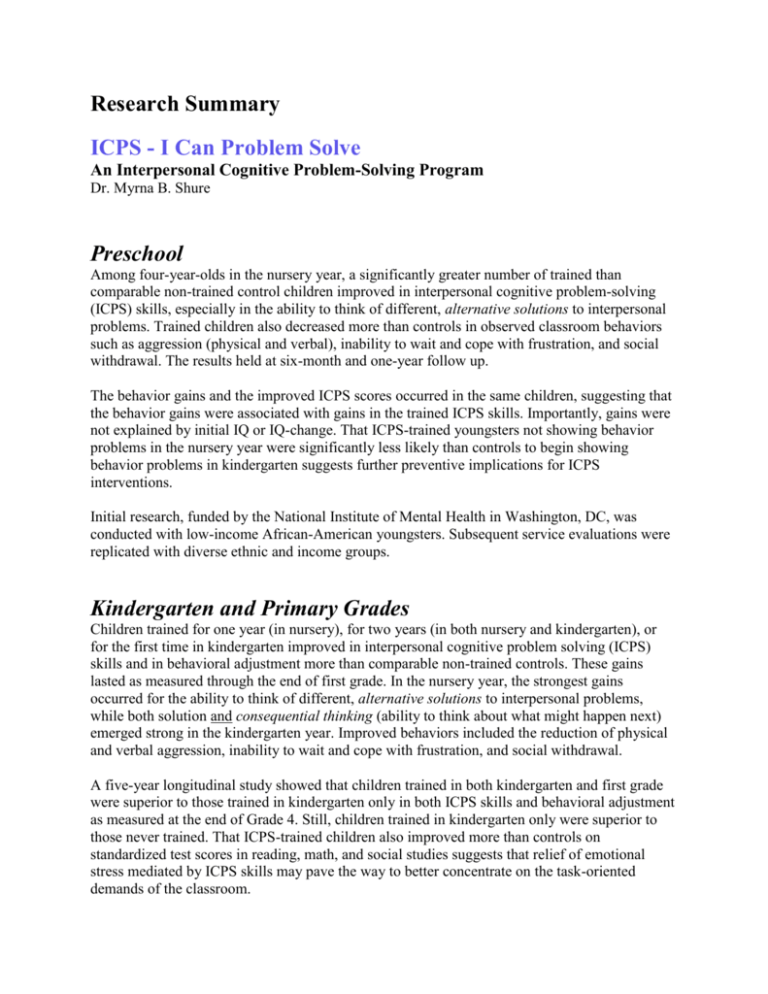

Research Summary ICPS - I Can Problem Solve An Interpersonal Cognitive Problem-Solving Program Dr. Myrna B. Shure Preschool Among four-year-olds in the nursery year, a significantly greater number of trained than comparable non-trained control children improved in interpersonal cognitive problem-solving (ICPS) skills, especially in the ability to think of different, alternative solutions to interpersonal problems. Trained children also decreased more than controls in observed classroom behaviors such as aggression (physical and verbal), inability to wait and cope with frustration, and social withdrawal. The results held at six-month and one-year follow up. The behavior gains and the improved ICPS scores occurred in the same children, suggesting that the behavior gains were associated with gains in the trained ICPS skills. Importantly, gains were not explained by initial IQ or IQ-change. That ICPS-trained youngsters not showing behavior problems in the nursery year were significantly less likely than controls to begin showing behavior problems in kindergarten suggests further preventive implications for ICPS interventions. Initial research, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health in Washington, DC, was conducted with low-income African-American youngsters. Subsequent service evaluations were replicated with diverse ethnic and income groups. Kindergarten and Primary Grades Children trained for one year (in nursery), for two years (in both nursery and kindergarten), or for the first time in kindergarten improved in interpersonal cognitive problem solving (ICPS) skills and in behavioral adjustment more than comparable non-trained controls. These gains lasted as measured through the end of first grade. In the nursery year, the strongest gains occurred for the ability to think of different, alternative solutions to interpersonal problems, while both solution and consequential thinking (ability to think about what might happen next) emerged strong in the kindergarten year. Improved behaviors included the reduction of physical and verbal aggression, inability to wait and cope with frustration, and social withdrawal. A five-year longitudinal study showed that children trained in both kindergarten and first grade were superior to those trained in kindergarten only in both ICPS skills and behavioral adjustment as measured at the end of Grade 4. Still, children trained in kindergarten only were superior to those never trained. That ICPS-trained children also improved more than controls on standardized test scores in reading, math, and social studies suggests that relief of emotional stress mediated by ICPS skills may pave the way to better concentrate on the task-oriented demands of the classroom. Initial research, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health in Washington, DC, was conducted with low-income African-American youngsters. Subsequent service evaluations through grade 3 were successfully conducted with diverse ethnic and income groups, as well as those with special needs including Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Intermediate Elementary Grades ICPS-trained 5th-graders improved more than those trained in an impersonal critical thinking (CT) program in alternative solution thinking (ability to think of different, alternative solutions to interpersonal problems), consequential thinking (ability to think about what might happen next), and means-ends thinking (ability to plan sequenced steps to reach an interpersonal goal). These gains occurred at the end of grade 5, and were maintained through grade 6. In grade 5, ICPS-trained youngsters improved in positive, prosocial behaviors more than CTtrained groups in behaviors such as showing concern for peers in distress, and being liked by their classmates. Those trained in both grades 5 and 6 improved most in measured negative impulsive behaviors, such as impatience, overemotionality, and aggression, and also behaviors describing social withdrawal. That some negative behaviors increased in CT controls from grades 5 to 6 adds support for ICPS as a viable approach to prevention. Standardized achievement test scores and reading grade levels also improved in ICPS-trained more than in CT-trained groups, suggesting that less stress fostered by ICPS skills may allow children to concentrate better on the task-oriented demands of the classroom, and subsequently, do better in school. Initial research, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health in Washington, DC, was conducted with low-income African-American youngsters. Subsequent service evaluations beginning in grade 3 were successfully conducted with diverse ethnic and income groups, as well as those with special needs including Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).