The Importance Of Being Symmetrical: Changeover To Reality (1982)

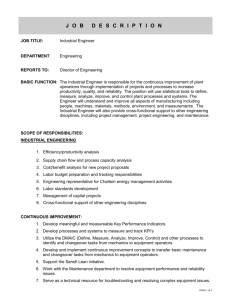

advertisement

Back to Realism Applied to Home Page Australian Journal of Psychology, Vol 34, No. 3, 1982 pp. 407-409 Symmetric_82.doc THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING SYMMETRICAL: CHANGEOVER TO REALITY G. B. BIEDERMAN and J. J. FUREDY University of Toronto In response to Harsh and Badia (1982) we show (as, e.g., in Biederman & Furedy, 1979) that Badia and co-workers1 asymmetrical form of changeover procedure is irrelevant to the empirically-complex preference-for-signalled-shock phenomenon. Harsh and Badia (1982) claim that our criticisms of Badia and Culbertson’s (1972) asymmetrical changeover procedure (ACP) are incorrect because (1) we “misunderstand” the details or the ACP and (2) we fail to consider baseline performance as a reference point when judging changeover (CO) behavior.1 It is tempting to counter such claims by exhaustive textual analysis. However, in view of the extensive commentary on ACP that already exists in the literature we shall restrict our comments to the misrepresentation by Harsh and Badia that the procedure we have criticized is the one detailed in their 1982 comment. Harsh and Badia’s (1982) Fig. 1 does not depict the asymmetrical changeover procedure (ACP) used by Badia and co-workers in the Bowling Green laboratory. For example, in the original Badia and Culbertson (1972) study cited by Harsh and Badia (1982), the direction of changeover was always from unsignalled to signalled state and never vice versa. The arrangements depicted in Harsh and Badia’s (1982) Fig. 1 are symmetrical (at least between subjects), inasmuch as some subjects changeover from A to B (left side of their Fig. 1) and others from B to A (right side of their Fig. 1). These arrangements, in fact, correspond to those used by the Rutgers laboratory (e.g., Safarjan & D’Amato, 1978); we have never criticized this form of symmetrical changeover procedure. This misrepresentation may be unclear to some readers because of Harsh and Badia’s failure (a) to indicate in their text to what specific papers their figure refers, and (b) to note that the title of the Safarjan and D’Amato paper that they cite contains the term “symmetrical” as a qualifier of “changeover design”. Although Harsh and Badia’s (1982) note purports to reveal the various misunderstandings and misrepresentations existing in the Biederman and Furedy (1979) paper, they omit the qualifier “asymmetrical” when describing the Bowling Green-changeover procedure, in contrast to our consistent and frequent use of this term. The point is that rightly or wrongly, it was the asymmetrical form of the changeover procedure that we were criticizing. The most critical issue is whether the asymmetrical changeover procedure (ACP) is actually adequate as a measure of the preference-for-signalled-shock 1 This critique of the ACP has not been restricted to the 1979 paper (Biederman & Furedy, 1979) but spans the decade following the appearance of the apparently spectacular evidence for preference for signaled (purportedly inescapable) shock provided by the Bowling Green laboratory (i.e., Badia & Culbertson, 1972; Badia, Culbertson, & Harsh, 1973; Badia, Coker, & Harsh, 1973). In addition to the 1979 paper, there are others examining the various problems with ACP: Biederman and Furedy (1973,1976a, 1976b, 1976c; 1977), Biederman, Furedy, & Beatty (1981) and Furedy and Biederman (1976a, 1976b, 1981). Requests for reprints should be sent to G. B. Biederman, Scarborough College, Division of Life Sciences, University of Toronto, West Hill, Ontario, MIC 1A4, Canada. 408 Biederman and J. J. Furedy (PSS) phenomenon, but insofar as the opinions of some experts on this issue are relevant, we note that the Rutgers laboratory agrees with us on the methodological difficulties associated with asymmetricality (Safarjan & D’Amato, 1978, p. 317). That is true even though the Toronto and Rutgers laboratories are in strong disagreement regarding the robustness of the PSS phenomenon itself (cf., Biederman & Furedy, 1979, p>p. 105-107; D’Amato, 1974, p. 93; Furedy, 1975, pp. 79-81). Methodological inadequacies aside, the Bowling Green ACP is unreliable in the sense of having been found impossible to reproduce. There are also technical problems which prevent it being characterizable as dealing with genuinely inescapable shock. This set of facts has been summarized elsewhere (Furedy & Biederman, 1981, pp. 372-374). Earlier papers (Biederman & Furedy, 1976c, 1977 have provided details and, in the 1976c paper, included relevant photographs of unauthorized shock escape in the box used by the Bowling Green laboratory. Further comment, therefore, seems superfluous except to point the reader to the conclusions section of our 1979 review (Biederman & Furedy, 1979, pp. 113-144) which still stands despite Harsh and Badia’s comments. REFERENCES BADIA, P., COKER, C. C, & HARSH, J. Choice of higher density signaled shock over lower density unsignaled shock. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 1973, 20, 47-55. BADIA, P., & CULBERTSON, S. The relative aversiveness of signaled vs. unsignaled escapable and inescapable shock. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 1972, 17, 463-471. BADIA, P., CULBERTSON, S., & HARSH, J. Choice of longer or stronger signaled shock over shorter or weaker unsignaled shock. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 1973, 19, 25-32. BIEDERMAN, G. B., & FUREDY, J. J. Preference-for-signalled-shock phenomenon: Effects of shock modifiability and light reinforcement. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1973, 100, 380-386. BIEDERMAN, G. B., & FUREDY, J. J. The preference-for-signalled-shock phenomenon: Fifty days with scrambled shock in the shuttle-box. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 1976, 7, 129-132. (a) BIEDERMAN, G. B., FUREDY, J. J. Operational duplication without behavioral replication of changeover for signaled inescapable shock. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 1976, 7, 421-424. (b) BIEDERMAN, G. B., & FUREDY, J. J. Preference for signaled shock in rats? Instrumentation and methodological errors in the archival literature. Psychological Record, 1976, 26, 501-514. (c) BIEDERMAN, G. B., & FUREDY, J. J. The preference-for-signalled-shock phenomenon: Reliability and sensitivity of asymmetrical and symmetrical changeover procedures in the Skinner box. Australian Journal of Psychology, 1977,29, 111-124. BIEDERMAN, G. B., & FUREDY, J. J. A history of rat preference for signalled shock: From paradox to paradigm. Australian Journal of Psychology, 1979, 31,101-118. BIEDERMAN, G. B., FUREDY, J. J., & BEATTY, J. G. The preference-for-signaled-shock phenomenon: Classical conditioning paradigms. Psychological Record, 1981, 31, 357-369. The Importance of Being Symmetrical 409 D’AMATO, M. R. Derived motives. Annual Review of Psychology, 1974, 25, 83-106. FUREDY, J. J. An integrative progress report on informational control in humans: Some laboratory findings and methodological claims. Australian Journal of Psychology, 1975, 27, 61-83. FUREDY, J. J., & BIEDERMAN, G. B. Preference-for-signaled-shock phenomenon: Direct and indirect evidence for modifiability factors in the shuttle-box. Animal Learning and Behavior, 1976, 4t 1-5. (a) FUREDY, J. J., & BIEDERMAN, G. B. The preference-for-signalled-shock phenomenon: A taxonomy of original type and signal content. Australian Journal of Psychology, 1976, 28, 167-169. (b) FUREDY, J. J., & BIEDERMAN, G. B. The asymmetrical changeover procedure in the preference-for-signaled-shock literature: The penultimate word? The Psychological Record, 1981, 31, 371-376. HARSH, J., & BADIA, P. Changing over to signaled shock schedules: A reply to Biederman and Furedy. Australian Journal of Psychology, 1982, 34, 403-406. SAFARJAN, W. R., & D’AMATO, H. R. Variables affecting preference for signaled shock in a symmetrical changeover design. Learning and Motivation, 1978, 9, 314-331. Received 23 June 1982. Australian Journal of Psychology, Vol 34, No. 3, 1982 pp. 403-406 NOTES AND COMMENTS CHANGING OVER TO SIGNALED SHOCK SCHEDULES: A REPLY TO BIEDERMAN AND FUREDY J. HARSH University of Southern Mississippi and P. BADIA Bowling Green State University Biederman and Furedy (1979) questioned in this journal the widely accepted conclusion that subjects prefer signaled over unsignaled shock schedules. The primary basis for their view is their objection to the changeover procedure used to assess preference. Our note reveals that their objections are based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the procedure. Biederman and Furedy (1979) recently reviewed studies dealing with choosing between signaled and unsignaled shock schedules. They concluded that the evidence is insufficient to support the statement that signaled schedules are preferred. This conclusion contrasts sharply with those of Badia, Harsh, and Abbott (1979). Badia et al. conclude that signaled schedules are strongly preferred over unsignaled ones and that the preference occurs across species and procedures. We believe that Biederman and Furedy’s conclusions are misleading to readers of this journal. Their conclusions result from their fundamental misunderstanding of the changeover procedure that is frequently, but not exclusively, used to study choice. Their review has other shortcomings and we have presented a full treatment of these and related issues elsewhere (Badia & Harsh, 1977a, 1977b; Harsh, 1978). In this note we describe the specific ways in which Biederman and Furedy misunderstand and misrepresent the changeover procedure. Characteristics of the Changeover-Choice Method The changeover method provides a means of comparing the relative value of two conditions. Usually two types of sessions are involved: (a) training, and (b) changeover. Training sessions serve two purposes: (1) the subjects experience the contingencies of one or both conditions, and (2) a changeover baseline is established. The changeover sessions are so named because subjects are given the opportunity to “changeover” from one condition to a second. As indicated in Fig. 1, there are two possible changeover arrangements. The left side of the diagram (CO A to B) represents an arrangement where test sessions begin with Condition A in effect, and subjects are given the opportunity to changeover for brief periods of Requests for reprints should be sent to John Harsh, Department of Psychology, Southern Station Box 9371, University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, Mississippi 39401, U.S.A. 404 J. Harsh and P. Badia time to Condition B. That is, when Condition A is in effect, a response (R) on the changeover manipulanda results in a change from Condition A to Condition B. When produced, Condition B remains in effect for a fixed period of time, the changeover period (COP), at the end of which Condition A is automatically reinstated. Not responding (R) during Condition A has no programmed consequences — when the subject does not respond, Condition A remains in effect. The right side of the diagram (CO B and A) describes the reverse arrangement. Here subjects begin each session with Condition B in effect and changeover responses produce brief periods of exposure to Condition A. Biederman and Furedy ‘s Criticisms Biederman and Furedy (1979) describe difficulties with the changeover method. In what follows, we show that their concerns are due to their misunderstanding of the method. Choice response asymmetry? Biederman and Furedy consider “choice response asymmetry’1 to be the most fundamental problem of the changeover procedure. In their words, the problem is that radically different responses (bar-press and withholding-of-bar-press) lead to the two states (signaled and unsignaled, respectively) for which unbiased preference is intended to be measured, (p. 109) Biederman and Furedy are simply mistaken in this belief. None of the studies to which they refer evaluated preference by comparing responding with non-responding. Preference is always evaluated by comparing responding in one situation with baseline responding in another situation. Response rates at above (below) baseline levels have been taken to indicate the relatively greater (lesser) value of the changeover condition. When changeover has not varied from baseline levels, no statements have been made about relative value. FIG 1. A diagram of the changeover method showing two possible arrangements. During a “CO A to B” test (left side of the diagram), Condition A continues in the absence of respon Jing (R). Responses (R), however, change Condition A to Condition B for a fixed changeover period (COP). During a “CO B to A” test (right side) changeover is from Condition B to Condition A. Signaled Shock Schedules 405 Asymmetry of response-stimulus contingencies? The problem identified here is behavior taken to index signaled preference ... is sometimes immediately followed by a clear consequence — the change from unsignaled to signaled state — so that in this case there is a relatively clear contingency between a homogeneous response (bar press) and a consequent stimulus ... On the other hand, the no-bar-press-for-three-minutes behaviours taken to index unsignaled preference do not have a parallel contingency between a single type of response and an immediately consequent stimulus. (Biederman & Furedy, 1979, p. 110) . This criticism again reflects their misunderstanding of the changeover method and relates to our first comment. Specifically, “no-bar-press-for-three-minutes behaviours” (i.e., non-responding) is not taken as an index of unsignaled preference. Biederman and Furedy apparently have the mistaken impression that once a subject has changed from an unsignaled to a signaled condition for a programmed three-minute period, further responding will prevent reinstatement of the unsignaled condition. Reinstatement of the unsignaled condition, however, is independent of responding in the changeover arrangement under consideration. Indicator—stimulus ambiguity? Biederman and Furedy’s third criticism concerns whether changeover behaviour that occurs at above baseline levels can be interpreted. The problem they address is that changing from an unsignaled to a signaled condition may be due either to: (a) the importance of being able to predict the occurrence (or nonoccurrence) of shock, or (b) the properties of the stimulus (e.g., light vs. darkness) that is used to identify the signaled shock condition. They focus on the latter and argue that this feature invalidates changeover choice measures. Biederman and Furedy, however, have overlooked the fact that proper controls for such specific effects have been used in changeover studies (see for example, Badia & Culbertson, 1972; Safarjan & D’Amato, 1978). Dependent-variable measure? In discussing this problem, Biederman and Furedy state that the dependent variable (time spent in the signaled condition) is “confounded” by the operant rate of responding. Unfortunately, in leveling this criticism, Biederman and Furedy have failed to consider that baseline levels for both time and rate can be and have been determined when the CO method has been used. Asymmetry of interpretation? Biederman and Furedy are concerned here with interpreting the results when subjects who value the unsignaled schedule more are given the opportunity to change from it to a signaled schedule. They imply again in this case that non-responding will be used as an index of preference. Again they are mistaken. The absence of changeover responding is never taken as an index of preference. It is always responding compared to baseline levels. In this instance, preference for the unsignaled schedule is assessed by giving subjects the opportunity to change from the signaled to the unsignaled schedule. REFERENCES BADIA, P., & CULBERTSON, S. The relative aversiveness of signalled vs unsignalled escapable and inescapable shock. Journal of Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 1972, 77, 462-471. BADIA, P., & HARSH, J. Preference for signaled over unsignaled shock schedules: A Reply to Furedy & Biederman. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 1977, 10, 13-16. (a) 406 J. Harsh and P. Badia BADIA, P., & HARSH, J. Further comments concerning preference for signaled shock conditions. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 1977, 10, 17-20. (b) BADIA, P., HARSH, J., & ABBOTT, B. Choosing between predictable and unpredictable shock conditions: Data and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 1979, 86, 1107-1131. BIEDERMAN, G. B., & FUREDY, J. J. A history of rat preference for signalled shock: From paradox to paradigm. Australian Journal of Psychology, 1979, 31, 101-118. HARSH, J. Preference for signaled shock: A well established and reliable phenomenon. The Psychological Record, 1978, 28, 281-289. SAFARJAN, W. R., & D’AMATO, M. R. Variables affecting preference for signaled shock in a symmetrical changeover design. Learning and Motivation, 1978, 9, 314-331. Received 9 March 1982.