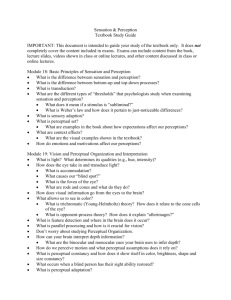

Perception and generality

advertisement