Chapter 2-Breeding objectives

advertisement

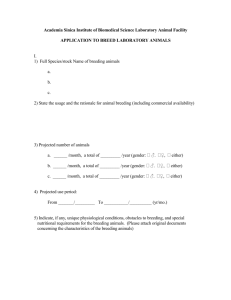

Production systems, population structures, breeding objectives 1 Understanding a production system Characterizing the production systems is a first natural step in designing alternative breeding strategies (Dossa et al., 2009; FAO, 2010; Philipsson et al., 2006; Scherf and Tixier-Boichard, 2009). This exercise comprises various components such as the characterization of production and product use at household level, breed description, livestock population structure and land use, and the role of livestock at household and community level. A market analysis is important for more commercial oriented systems as well as study of directional livestock policy documents, if valid for the region or country. These studies show the context under which livestock is kept and what are the reasons for keeping animals. In addition, infrastructure such as availability of AI services and/or extension services should be documented. Identification of breeds involves phenotypic characterization using a purposive sampling strategy. Qualitative and quantitative physical measurements of animals and their production required for identifying and describing distinct populations or breeds are collected through surveys. For this purpose, a comprehensive list of animal descriptors has been developed by FAO (1986). Genetic characterization of the population may be done with a recommended set of microsatellites (FAO, 2005) or using SNPs. Many characterization studies were not done with the ultimate goal of designing and implementing breeding programs. Therefore information about the livestock population structure is often not available. This structure should be documented at household, community and regional level. Finally, the information from different studies has to be combined and jointly analyzed. The results of such an exercise can be used as a decision support tool if animal breeding is found to be a proper intervention for the studied system. If no, what are alternative ways of intervention, and if yes, what alternative breeding schemes should be developed and finally implemented. Tools for characterizing production systems The information can be collected by standard methods of Rapid Rural Appraisal and farm monitoring. Rapid Rural Appraisal consists of a series of techniques that help to generate information in a time efficient manner and incorporates the knowledge and opinions of rural people in the planning and management of projects (Chambers, 1998). Survey studies using questionnaires and checklists for individual household interviews are commonly done. Other interview partners can be official livestock development officers from Ministries to get also other opinions and views on the topic. Findings are often cross-checked and validated in workshops. If a breeding program should be implemented with more than one community, surveys and discussions with relevant stakeholders have to cover all potentially participating communities. 1 2 2 Breeding objectives Methods for identification of farmers´ preferences for specific breeds and local breeding objectives have received some attention, although the literature dealing with breeding objectives and related questions is diverse. Some authors investigated farmers´ preferences for specific breeds or types of animals (Bebe et al., 2003; Ouma et al., 2004; Roessler et al.,2008; Scarpa et al., 2003a, 2003b; Tano et al., 2003). These studies aim to understand the reasons for choosing an animal of a local breed, a crossbred animal or one of an exotic breed. Another group of authors look at the function of livestock in the production system and at its relevance and importance for the livelihood of farmers (Markemann and Valle Zarate, 2010; Markemann et al., 2009). Other authors investigate local or indigenous selection criteria and breeding objectives practiced in various production systems (Adams et al., 2002; Escareño Sanchez, 2010; Herold et al., 2009; Jaitner et al., 2003; Lanari et al., 2005; Ndumu et al., 2008; Perezgrovas, 1995; Wurzinger et al., 2006). These papers highlight the importance of valuing the knowledge of livestock keepers and stress the point that this information has to be taken into account while formulating breeding programs. The authors remain often vague in their statements without giving the reader guidelines which traits should finally be used. Gender differences in the ranking of important selection criteria were sometimes observed. Nevertheless, it remains unclear how the different approaches for determination of breeding objectives should be addressed in a breeding program. In general, the breeding objectives have to be in line with market demand and foreseen future use of animal products. The information about the market demand has to be collected in the characterisation of the production system (see previous chapter). A cross-check of the current breeding objectives of the communities and the market demands allows a validation of the suitability of current objectives. A clear definition of the breeding objectives is necessary at the design stage of the breeding program, but has to be revised at regular intervals during the execution of the program. These breeding objectives have to been seen in relation with resources and infrastructure available. It has to be analysed if the current population of animals may actually respond to the defined breeding goal. Studies on population size and the phenotypic variation observed in relevant traits, together with genetic parameters found for similar traits in other populations, may be helpful in this respect. If it is not likely to successfully apply a within breed selection program, options of cross-breeding for infusion of genes from other superior populations to boost the level of production should be evaluated. Crossbreeding for milk and meat could be viable options (e.g. Red Maasai sheep crossed with Dorper to get a marketable product, or the development of a synthetic cattle breed as Sunandini in India). Before entering a crossbreeding program the availability of feed resources has to be assessed and cross-checked if they can support the proposed goal. This is especially important if selection is on growth as higher growth rate also results in higher mature weights and higher feed requirements for growth and maintenance. The choice of expanding the small or large ruminant population may be crucial when assessing the potential for increased productivity when feed resources are limited. 3 The possibly long list of selection traits that farmers may suggest to include needs to be reduced to a minimum, but should at least include one production trait and one reproduction trait reflecting the adaptability of the animals to the prevailing environmental conditions. It would be preferable to include composite traits (e.g. number of weaned lambs/ewe or weaned weight/ewe) in the breeding objectives as this reflects also adaptation. Early maturity and regularity in reproductive performance under harsh and variable climatic conditions are important adaptation traits contributing to the longevity of animals. The inclusion of specific adaptive traits, as suggested by some authors, seems rather ambiguous as they are difficult to measure under field conditions, especially under smallholder conditions. One such potential trait could be “fecal egg count”, which is an estimate for resistance against internal parasites. This trait might only be useful to include if there is a high parasitic pressure in the system. Tools for assessing breeding objectives A restricted or desired gain index should be used to ensure that no unwanted negative trends will be observed in specific important traits. One example would be to prevent fertility from declining over time. It is important to get progress in the most important traits set, because otherwise farmers loose interest in the breeding program and might drop out. Including only the farmers´ view bears the risk of continuing with the current status. For that reason the role of scientists is to bring in their expertise and knowledge and blend these sets of information. Otherwise the classical approach for the assessment of different traits in breeding objectives is the derivation of their economic values. The drawback of this method is that lots of input information is needed, which is not readily available in many situations. Therefore it might be better to weigh relative importance of traits when formulating an index following the guidelines of FAO (2010). It is also argued that this approach neglects the manifold roles of livestock in the system and that tangible and intangible values of animals are not considered (Kosgey et al., 2004). In the last years different participatory methods or tools have been tested to identify selection criteria of farmers. All these papers have in common that only one method has been tested, but there is no comparison made if results may differ between different approaches used. Hypothetical choice experiments (“Choice cards”), personal interviews, workshops and ranking experiments of live animals (known or not known by farmers) are currently used to define breeding objectives in a participatory manner. Although the results of such exercises with farmers are sometimes somehow predictable, it is still important to guide people through this process. It creates awareness of the importance of breeding, can help to clarify expectations about possible changes which can be achieved through breeding and create ownership of the breeding program amongst participants as they can see that their knowledge and perceptions are taken into consideration. 4 In Table X advantages and possible disadvantages of the different participatory approaches are listed. Our observation is that none of these methods is a standalone one and therefore each method should be combined with another one. This will help to reduce the risk of overlooking important traits. Table X. Comparison of advantages and disadvantages of alternative methods where participatory approaches are practiced Properties Personal interviews Workshops General comments Choice cards Ranking of live animals Ranking of own animals Ranking of animals unknown to farmers Access to farmers is often difficult - Clear sampling strategy needed Unclear results, if farmers have no common breeding goal - Large sample size - Relatively easy to handle - Enumerator introduced - Closer to reality than choice bias likely to be lower than cards: Seeing a live animal is in interviews better than a picture - Price can be included as a - Information from different characteristic family members can be - Possible to value considered intangible traits Information on not visible traits can be considered - Advantages - A large number of persons can be interviewed - Possible to verify the consistency of responses - Additional information can be gathered at the same time Disadvantages - Language barrier - Enumerator introduced bias may be high - Important traits may not be mentioned - Information from different persons collected at once Differences can be directly discussed - Some people (e.g. with higher social status) might dominate the discussion - Limited number of animal profile choices can be made per person - Visual illustration of some traits can be complicated or impossible - Enumerator introduced bias - Perceiving the different attributes of a given choice set as attributes of - There may not be enough animals of the same category available in small herds - Easily done by farmers - Closer to reality than choice cards: seeing a live animal is better than a picture - Large “pool” of animals often not readily available - Hypothetical life history provided with a given animal may not be compatible with the visual appearance according to farmers’ experience. - 5 an animal is difficult (i.e. conscious level an interview matters) 6 References Adams, M., Kaufmann, B., Valle-Zarate, A., 2002. Indigenous characterisation of local camel populations and breeding methods of pastoralists in Northern Kenya. Proc. Deutscher Tropentag, vol. 2002. Witzenhausen, Germany. October 9–11, 2002. Bebe, B.O., Udo, H.M.J., Rowlands, G.J., Thorpe, W. 2003. Smallholder dairy systems in the Kenya highlands: breed preferences and breeding practices. Livestock Production Science 82, 117–127. Chambers, R. 1998. Farmer first. Farmer innovation and agricultural research. Intermediate Technology Publ., London. Dossa, L.H., Wollny, C., Gauly, M., Gbégo, I. 2009. Community-based management of farm animal genetic resources in practice: framework for local goats in two rural communities in Southern Benin. Animal Genetic Resources information no 44, 2009. Escareño Sanchez, L. 2010. Diseño e implementación de un programa de mejoramiento genético de tipo comunitario de caprinos en el norte de México. PhD thesis. University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Scienes Vienna, Austria. FAO. 1986. FAO. 2005. FAO. 2010. Breeding strategies for sustainable management of animal genetic resources. FAO Animal Production and Health Guidelines. No. 3. Rome. Herold, P., Wenzler, J.-G., Jaudas, U., Kanz, C., Valle Zárate, A. 2009. User specific breeding goals in dairy goat breeding, EAAP 2009, Barcelona. Jaitner, J. Corr, N., Dempfle, L. 2003. Ownership patterns and Management practices of cattle herds in the Gambia: Implications for a breeding program. Tropical animal health and production 35, 179187. Kosgey, I. S., Van Arendonk, J. A. M., Baker, R. L. 2004. Economic values for traits in breeding objectives for sheep in the tropics: impact of tangible and intangible benefits. Livestock Production Science 88: 143–160. Lanari, M. R., Domingo, E., Pérez Centeno, M. J., Gallo, L. 2005. Pastoral community selection and the genetic structure of a local goat breed in Patagonia. Animal Genetic Resources Information 37: 31-42. Markemann, A., Valle Zárate, A.2010. Traditional llama husbandry and breeding management in the Ayopaya region, Bolivia. Tropical Animal Health and Production 42:79–87. Markemann, A., Stemmer, A., Siegmund-Schultze, M., Piepho, H.P., Valle Zárate, A. 2009. Stated preferences of llama keeping functions in Bolivia. Livestock Science 124: 119–125. Ndumu, D.B., Baumung, R., Wurzinger, M., Drucker, A.G., Okeyo, A.M., Semambo, D., Sölkner, J. 2008. Performance and fitness traits versus phenotypic appearance in the African Ankole Longhorn 7 cattle: A novel approach to identify selection criteria for indigenous breeds, Livestock Science 113: 234–242. Ouma, E., Abdulai, A., Drucker, A.G., Obare, G., 2004. Assessment of farmer preferences for cattle traits in smallholder cattle production systems of Kenya and Ethiopia. Proc. Deutscher Tropentag 2004. Humboldt-University Berlin, Germany. October 5 to 7, 2004. Perezgrovas, R., 1995. Collaborative application of empirical criteria for selection high quality fleeces: Tzotzil shepherdesses and sheep scientists work together to develop tools for genetic improvement. http://www.unesco.org/most/bpik17-2.htm. Philipsson, J., Rege, J.E.O. and Okeyo, A.M. 2006. Sustainable breeding programs for tropical farming systems. In J.M. Ojango, B.Malmfors, and A.M. Okeyo, eds. Animal genetics training resource. CD. Version 2. International Livestock Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya, and Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden. Roessler, R., Drucker, A., Scarpa, R., Markemann, A., Lemke, U., Thuy, L.T. and Valle Zárate, A. 2008. Using choice experiments to assess smallholder farmers' preferences for pig breeding traits in different production systems in North-West Vietnam. Ecol. Econ. 66, 184-192. Scherf, B., Tixier-Boichard, M. 2009. Production environment recording. Animal Genetic Resources information no 44, 2009. Scarpa, R., Ruto, E.S.K., Kristjanson, P., Radney, M., Drucker, A.G., Rege, J.E.O., 2003a. Valuing indigenous cattle breeds in Kenya: an empirical comparison of stated and revealed preference value estimates. Ecol. Econ. 45 (3), 409–426. Scarpa, R., Ruto, E.S.K., Drucker, A.G., Anderson, S., Ferraes-Ehuan, N., Gomez, V., Rizopatron, C.R., Rubio-Leonel, O., 2003b. Valuing genetic resources in peasant economies: the case of ‘hairless’ creole pigs in Yucatan. Ecol. Econ. 45 (3), 427–443. Tano, K., Kamuanga, M., Faminow, M.D., Swallow, B., 2003. Using conjoint analysis to estimate farmers' preferences for cattle traits in West Africa. Ecol. Econ. 45 (3), 393–407. Wurzinger, M., Ndumu, D., Baumung, R., Drucker, A. G., Okeyo, A. M., Semambo, D. K. Sölkner, J. 2006. Assessing stated preferences through the use of choice experiments: valuing (re)production versus aesthetics in the breeding goals of Ugandan Ankole cattle breeders. 8th World Congress on Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, August 13-18, 2006, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. 8